Scott Alexander reviews The Third Revolution, by Elizabeth Economy, although as he says up front, “It’s a look through recent Chinese history, with The Third Revolution as a very loose inspiration.”:

How Does China’s Government Work?

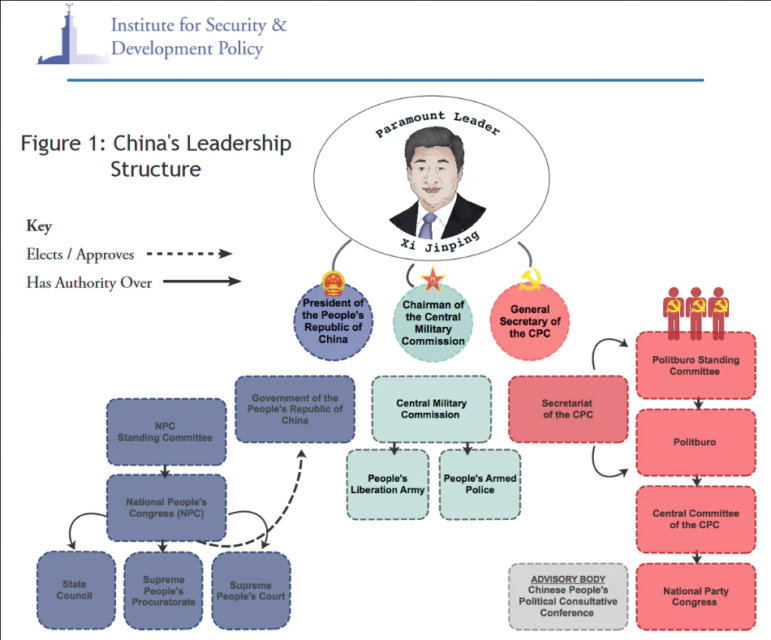

The traditional answer is a flowchart like this one (source):

But you could give a similarly convoluted flowchart for America, and it would tell people much less than words like “democracy” or “balance of powers”. What’s the Chinese equivalent?

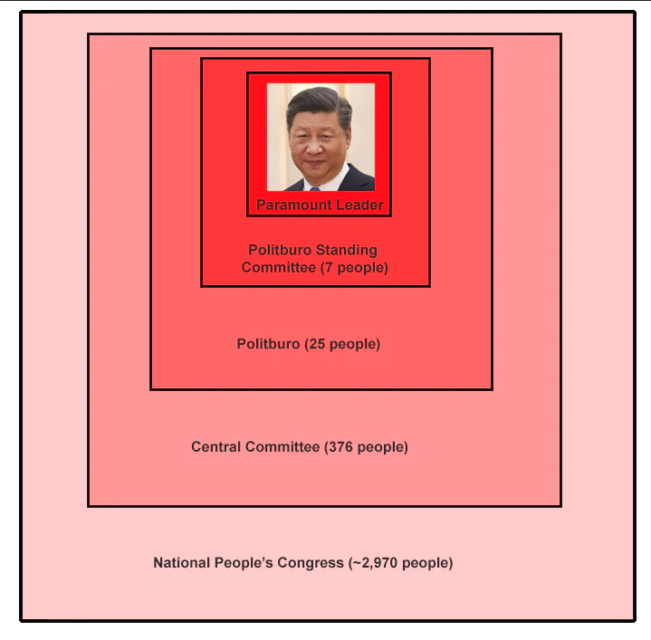

I found it a little more helpful to see it diagrammed it as a series of nested squares:

The inner levels have real power, and the outer layers are theoretically overseers but actually rubber stamps. Things get more and more rubber-stampy as you go out, culminating in the National People’s Congress, which recently voted to re-elect Xi by a vote of 2,970 in favor, 0 against — it’s so irrelevant that it’s literally called “the NPC”.

Who chooses the members of the inner groups? In theory, the outer groups; for example, the Central Committee is supposed to elect the Politburo Standing Committee. In practice, these selections tend to be of the “2,970 in favor, 0 against” variety, so they must be taking marching orders from someone. Who? The Chinese government doesn’t talk about it much, but probably the members of the Politburo Standing Committee hand-pick everyone, including the Paramount Leader and their own successors.

How do they pick? Mostly patron-client relationships. Every leading politician cultivates a network of loyal supporters; if he takes power, he tries to put as many of his people into top posts as he can. The seven Politburo members wheel and deal with each other about whose clients should get which positions, including any unoccupied Politburo seats.

If the two word description of US politics is “democracy, checks-and-balances”, then the two word description of Chinese politics is “oligarchy, patrons-and-clients”. If this seems exotic, it shouldn’t: it’s not much different from how the US fills unelected posts like “ambassador” and “White House staffer”. The Trump presidency put this into especially sharp relief, either because Trump did it more blatantly than usual or just because Trump’s clients were so obviously different from the normal Washington crowd. Consider eg the appointment of Jeff Sessions (among the first Congressmen to endorse Trump) as Attorney General.

In the US, this is a peripheral part of the system, checked by democracy. In China, it’s the whole game.