As soon as you see the recommendation from Noam Chomsky on the cover of the book, you can pretty much guess where McQuaig is coming from. I refer to the Chomskyan school of thought as American Monist: in short, the only actor on the world stage is America. It is the sole source of evil and depredation. Everyone else is motivated solely by love and concern for humanity, whilst America is, singularly, motivated only by greed, lust for power and a general animus for all things good, sunny and nice. Only America acts; everyone else is acted upon by the Hegemon, and can’t be blamed for the consequences of their actions. America is the Primus Mobilis. And America is bad. So, for example, the notion that an economy-based increased lust for oil is driving foreign policy is solely a characteristic of America; no other nation on earth appears to give a shit about oil. Certainly not France, Russia or China; McQuaig hardly mentions them. While McQuaig is forced to acknowledge that French, Russian and Chinese support for Saddam (and attendant undermining of UN sanctions) was related in some fashion to the oil deals they had each struck with Iraq, she airily dismisses the role that oil plays in their respective foreign policies. So the “oil as the root of all evil” trope is batted away in the space of two sentences when talking about other countries, but more than 300 pages are required to explain how oil and America are mutually catalyzing demon twins. When the rapaciousness of oil companies is discussed, it is almost exclusively American oil companies which are named; hardly ever any of the European, Russian or other oil companies. Because those other oil companies don’t possess the true indicia of evil, you see: they don’t stamp their barrels “Made in the USA”.

Bob Tarantino, “LIB Review: It’s the Crude, Dude”, Let It Bleed, 2005-03-05.

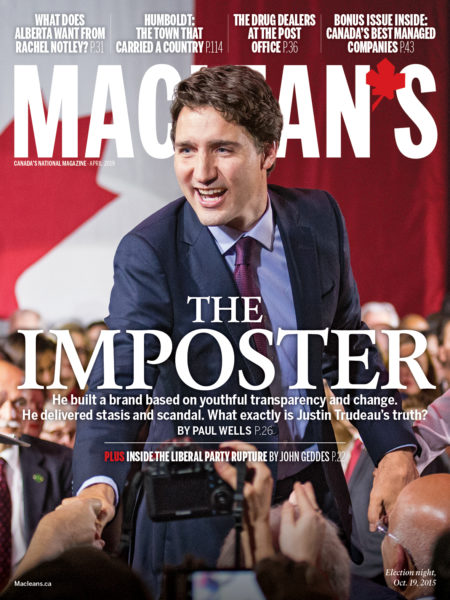

April 25, 2021

QotD: “The Great Satan”

January 1, 2021

The paradox of innovation – the more you have, the less impact each individual innovation has

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the oddity that as the British economy expanded during the early Industrial Revolution, each new discovery had less and less direct impact on the economy as a whole:

What this means is that when there were even some slight improvements in agriculture alone, the effects on living standards could be dramatic. But absent such improvements, a rich culture of innovation affecting everything from clothes to watches to books, wine, glassware, metals, and pottery would have been almost entirely masked from the figures. Importantly, the same applies not only to the composition of average notional consumption baskets, but to the contributions of different sectors to the economy as a whole. While the total amount of food has increased dramatically for the past few hundred years, for example, agriculture’s share of the economy steadily fell (from over 40% of the English economy in 1600, and an even greater share of total employment, to less than 1% today, with a similar trend repeated worldwide). So the relative importance of your typical agricultural innovation for overall growth rates has fallen dramatically. Perhaps it’s no wonder that twentieth-century agricultural pioneers like Norman Borlaug still don’t really get their due.

The same goes, more recently, for manufacturing. The reason the textbooks always name Kay, Hargreaves, Crompton, Cartwright and Arkwright, is because they made improvements to what was already one of the most important sectors of the economy: textiles. In the eighteenth century, textiles as a whole accounted for a whopping 16-17% of the British economy. So any growth in the value of wool, linen, and increasingly cotton goods, had an appreciable impact on overall economic growth. Today, by contrast, you’d be hard pressed to find many sectors that account for even 5% of the country’s economy (except construction, and possibly financial services, depending on how broadly you define them). And while Britain may have long lost its role as the workshop of the world, textile production in China today still only accounts for about 7% of the country’s economy. To put it another way, the modern Arkwrights and Cartwrights and Cromptons of China, to have any comparable effect on national statistics, would have to make productivity improvements to their industry that are at least three times as impressive.

And impressive they are, though you won’t have heard of them. Arkwright and Crompton multiplied the number of threads that a single machine could spin, from one to dozens. Today, thread is spun by the thousands, at speeds they could have scarcely comprehended, and with entire factories hardly needing a single pair of human hands. Automatic sensors monitor the yarn’s tension and detect any defects while it is being spun, with robots even whizzing along to repair any snaps, able to find a loose end and piece the yarn together again — a task that once required the nimble fingers of small children. From an eighteenth-century perspective, our textile machines routinely now do magic, and are getting ever more fantastical every day. Imagine showing Arkwright the use of lasers in fading and cutting jeans.

But by replacing human labour, innovation has become ever more hidden. Many people don’t realise that British manufacturing is actually larger and more valuable than ever. It’s just that it employs fewer people than ever, so hardly anybody gets to witness its great strides forwards (to witness a flavour of manufacturing’s modern marvels, I recommend checking out MachinePix).

And more importantly, the overall effect of each innovation has also been steadily diluted — itself the result of growth. Innovation has, in a sense, been the victim of its own success. By creating ever more products, sprouting new industries, and diversifying them into myriad specialisms, we have shrunk the impact that any single improvement can have. When cotton was king, a handful of inventors might hope to affect the entire national textile industry in some way. Nowadays, there’s not a chance. Doubling the productivity of cotton spinning is all well and good, but what about nylon, polyester, rayon, and the host of other fibres we have since invented? And which kind of spinning machine would you improve? An old-fashioned ring-spinner, a newer rotor spinner, or perhaps even one of the brand new air-jet types?

If you make an improvement, it’s not going to be to the industry as a whole — it’ll be specific. And actually improvements have always been specific; it’s just that the industries have since multiplied and narrowed. Inventors once made drops into a puddle, but the puddle then expanded into an ocean. It doesn’t make the drops any less innovative. This paradox of progress affects all innovation, such that it is no wonder that the number of researchers has been increasing while national-level productivity growth has appeared fairly stagnant. Even general-purpose technologies, like the recent dramatic improvements to telecommunications, computing, and software, have had a muted effect, being applied more slowly than we’d have liked. I expect that all future general-purpose technologies will fare even worse, for it takes still further effort and innovation to apply a technology to a given industry, and those industries will continue to multiply. All future general-purpose technologies, that is, except improvements to energy.

November 5, 2020

QotD: The idiocy of tariffs

The entire point of trade, the very purpose of it, is to gain access to the imports. Those things which Johnny Foreigner makes cheaper or better than we do. To tax ourselves because he makes things cheaper or better than we do is simple idiocy. […] Over and above this stupidity there’s the depressing point that trade and trade protection really is a spiral. Here we’ve got the two largest economies on the planet tripping over themselves to punish their own citizenry for their temerity in buying foreign. And as we can see, it is a tit for tat spiral. A little bit of sabre rattling, a response, a larger amount of shouting, a response, then truly impoverishing levels of rock throwing into own harbours and off we go into making our own people less wealthy.

The true sadness here being that the spiral works the other way too. But hugely, vastly, more slowly. GATT was founded in 1947, it became, the process was transferred to, the WTO and it has taken them since then, that two generations, to reduce tariff levels to where they’re not really all that important in trade matters. Something that is being undone in just a couple of months of foolishness. GATT being something of a response to the economic demolition work done by Smoot Hawley of course.

Trade protection does spiral up and spiral down, the sadness being that here’s an asymmetry to the process. The reductions that make us richer take very much longer than the nonsenses that impoverish.

Tim Worstall, “The China, US, Trade War – It’s All Mutual On The Way Down As Well As Up”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-07-11.

October 27, 2020

America’s “brutal system of slavery [was] unlike anything that had existed in the world before”

I missed this article by Kay S. Hymowitz when it was published by City Journal a couple of weeks back:

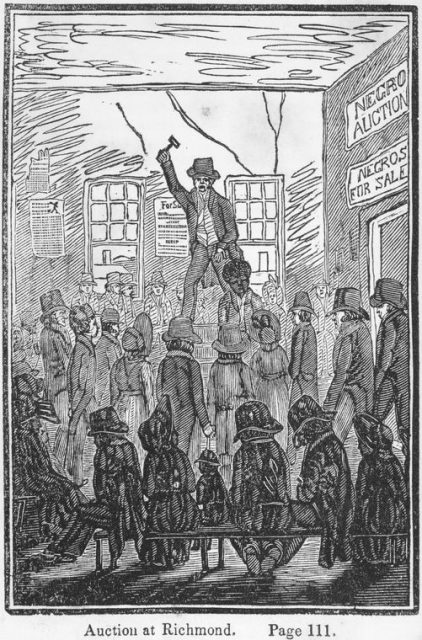

Auction at Richmond. (1834)

“Five hundred thousand strokes for freedom ; a series of anti-slavery tracts, of which half a million are now first issued by the friends of the Negro.” by Armistead, Wilson, 1819?-1868 and “Picture of slavery in the United States of America. ” by Bourne, George, 1780-1845

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons.

… slavery was a mundane fact in most human civilizations, neither questioned nor much thought about. It appeared in the earliest settlements of Sumer, Babylonia, China, and Egypt, and it continues in many parts of the world to this day. Far from grappling with whether slavery should be legal, the code of Hammurabi, civilization’s first known legal text, simply defines appropriate punishments for recalcitrant slaves (cutting off their ears) or those who help them escape (death). Both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament take for granted the existence of slaves. Slavery was so firmly established in ancient Greece that Plato could not imagine his ideal Republic without them, though he rejected the idea of individual ownership in favor of state control. As for Rome, well, Spartacus, anyone?

In the ancient world, slaves were almost always captives from the era’s endless wars of conquest. They were forced to do all the heavy labor required for building and sustaining cities and towns: clearing forests; building roads, temples, and palaces; digging and transporting stone; hoeing fields; rowing galley ships; and marching to almost-certain death in the front line of battle. Women (and often enough boy) slaves had the task of servicing the sexual appetites of their masters. None of that changed with the arrival of a new millennium. Gaelic tribes took advantage of the fall of the Roman Empire to raid the west coast of England and Wales for strong bodies; one belonged to a 16-year-old later anointed St. Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. “In the slavery business, no tribe was fiercer or more feared than the Irish,” writes Thomas Cahill in How the Irish Saved Civilization.

Today, of course, the immorality of slave-owning is as clear as day. But in the premodern world, no neat division existed between evil slaveowners and their innocent victims. Once the Vikings arrived in their longboats in the 700s, the Irish enslavers found themselves the enslaved. Slavery became the commanding height of the Viking economy; Norsemen raided coastal villages across Europe and brought their captives to Dublin, which became one of the largest slave markets of the time. The Vikings thought of their slaves as more like cattle than people; the unlucky victims had to sleep alongside the domestic animals, according to the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Norsemen rounded up captured Irish men and women to settle the desolate landscape of Iceland; scientists have found Irish DNA in present-day Icelanders, a legacy of that time. The Slavic tribes in Eastern Europe were an especially fertile supplier for Viking slave traders as well as for Muslim dealers from Spain: their Latin name gave us the word slave. Slavs were evidently not deterred by the misery they must have suffered; when Viking power waned by the twelfth century, the Slavs turned around and enslaved Vikings as well as Greeks.

Slavery was a normal state of affairs well beyond the territory we now call Europe. The Mayans had slaves; the Aztecs harnessed the labor of captives to build their temples and then serve as human sacrifices at the altars they had helped construct. The ancient Near East and Asia Minor were chockfull of slaves, mostly from East Africa. According to eminent slavery scholar Orlando Patterson, East Africa was plundered for human chattel as far back as 1580 BC. Muhammad called for compassion for the enslaved, but that didn’t stop his followers from expanding their search for chattel beyond the east coast into the interior of Africa, where the trade flourished for many centuries before those first West Africans arrived in Jamestown. Throughout that time, African kings and merchants grew rich from capturing and selling the millions of African slaves sent through the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean to Persians and Ottomans.

From the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the North African Barbary coast was a hub for “white slavery.” This episode was relatively short-lived in the global history of slavery, but one with overlooked impact on Western culture. Around 1619, just as the first Africans were being sailed from the African coast to Jamestown, Algerian and Tunisian pirates, or “corsairs” as they were known, were using their boats to raid seaside villages on the Mediterranean and Atlantic for slaves who happened in this case to be white. In 1631, Ottoman pirates sacked Baltimore on the southern coast of Ireland, capturing and enslaving the villagers. Around the same time, Iceland was raided by Barbary corsairs who took hundreds of prisoners, selling them into lifetime bondage.

September 2, 2020

Cold War 2.0 — you’re soaking in it

Ted Campbell responds to a recent article in Foreign Affairs by Nadia Schadlow:

Dr Schadlow posits that “A new set of assumptions should underpin U.S. foreign policy … [and, concomitantly, the foreign polices of the US led West, including Canada’s, because] … Contrary to the optimistic predictions made in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, widespread political liberalization and the growth of transnational organizations have not tempered rivalries among countries. Likewise, globalization and economic interdependence have not been unalloyed goods; often, they have generated unanticipated inequalities and vulnerabilities [and] although the proliferation of digital technologies has increased productivity and brought other benefits, it has also eroded the U.S. military’s advantages and posed challenges to democratic societies.”

After outlining the rosy assumption made by leaders and policy makers from Richard Nixon through Bill Clinton to Barack Obama ~ assumption which I shared, Nadia Schadlow says that “China had no intention of converging with the West [because] The Chinese Communist Party never intended to play by the West’s rules; it was determined to control markets rather than open them, and it did so by keeping its exchange rate artificially low, providing unfair advantages to state-owned enterprises, and erecting regulatory barriers against non-Chinese companies. Officials in both the George W. Bush and the Obama administrations worried about China’s intentions. But fundamentally, they remained convinced that the United States needed to engage with China to strengthen the rules-based international system and that China’s economic liberalization would ultimately lead to political liberalization. Instead, China has continued to take advantage of economic interdependence to grow its economy and enhance its military, thereby ensuring the long-term strength of the CCP.” Of course, from a Chinese perspective it might, very reasonably, appear that the liberal, US made (in the late 1940s) “rules based international system” was, in fact, designed to strengthen the US economy and enhance its military and ensure America’s long term strength … and that is not, many would say, a totally unreasonable view.

[…]

America’s allies, including Canada, need to step up and help the USA (and India) with the containment of both China and Russia in several regions: in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe, too. Canada is a G-7 nation. It needs to start acting like one.

Australians, Brits, Canadians and Danes need not share Dr Schadlow’s Trumpian view of the world and of Cold War 2.0 to understand that:

- It is here. We are in it, like it or not; and

- Like its predecessor, it can turn hot if we do not manage it with care.

Now, at this time, the conventional wisdom is that foreign and defence policy must take a back seat to beating COVID-19 and restarting the economy. But, the Chinese and the Russians are not putting their plans on hold while they deal with the pandemic. (Maybe that’s why Justin Trudeau admires China’s “basic dictatorship” so much.) They will both be moving ahead with plans that aim to put the US-led West, including Canada, at a disadvantage. Additionally, now is a good time to announce plans to build more new warships ~ two or three large helicopter carriers, another supply ship (for a total of four) 16 major surface combatants (the new Type 26 ships) and a dozen smaller corvettes … can be and politicians should say will be built here in Canada, by Canadian workers. Defence related projects, when well conceived and directed, can be great long-term job creators. Canada can do both: speed up our recovery from the pandemic and strengthen our global position by making defence procurement a priority for the recovery.

August 18, 2020

Don’t worry your pretty little heads, normies, the enlightened ones are planning “The Great Reset” for 2021

Mark Steyn on how the great and the good of the world are figuring out the road ahead of us:

… most of the chaps who matter in this world are people you’ve never heard of — by which I mean they are other than the omnipresent pygmies of the political scene: In a settled democratic society such as Canada, for example, if you wind up with an electoral contest between a woke mammy singer with a banana in his pants and a hollow husk less lifelike than his CBC election-night hologram whose only core belief is that he has no core beliefs other than that party donations should pay for his kids’ schooling, you can take it as read that the real action must be elsewhere.

A lot of those chaps you’ve never heard of turn up in this video from the “World Economic Forum” — ie, the Davos set. After five months of Covid lockdown, you’ll be happy to hear that all the experts have decided that 2021 will be the year of “The Great Reset”:

I see my chums at the Heartland Institute headline this the “World Leaders’ ‘Great Reset’ Plan“. But, if by “leader” you mean an elected head of government accountable to the people, there is a total dearth. Indeed, it’s a melancholy reflection on the state of “world leadership” that the nearest to anyone accountable to the people in this video is HRH The Prince of Wales, in whom one day in the hopefully extremely far distant future the executive authority of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, etc will be nominally vested but which cannot be exercised without the consent of the people’s representatives. Yet even that token accountability is, as noted, in the future. So right now he’s just another guy who’s a “world leader” because he gets invited to Davos and you don’t — and, even if you were minded to show up anyway, you’d need a private jet because all the scheduled flights have been Covid-canceled and the world’s airports are ghost towns.

As is the custom among our big thinkers, the blather is very generalized. “Now is the time to think about what history would say about this crisis,” says the head of the IMF. If you say so. Personally, I was thinking that now is the time to eat a meal in a restaurant, if they weren’t closed.

But, why is it history’s job to say something about this crisis? Why, don’t you “world leaders” of the here and now say anything about it? “It is imperative that we reimagine, rebuild, redesign, re-invigorate and re-balance our world,” declares the UN Secretary-General.

That’s almost a full set, but he forgot “redefined”. “Possibilities are being redefined each and every day,” says the chief exec of British Petroleum, who as is his wont sounds like he’s in any business other than petroleum.

There is, of course, an inscrutable Oriental, who is chairman of something called the “China Green Finance Committee”. He’s there as a not so subtle reminder not even to bring up the subject of China, whose lies amplified by their sock puppet at the WHO are the sole cause of the present crisis – and whose death-grip on our future is the thing that most urgently needs to be reimagined, rebuilt, re-balanced and redefined. As I’ve mentioned many times over the spring and summer, twenty years ago we were told to forget about manufacturing — from widgets to “These Colors Don’t Run” T-shirts, that’s never coming back; from now on, we’re going to be “the knowledge economy”. Yet mysteriously, with the 5G and the Huawei and all the rest, China seems to have snaffled all that, too.

July 6, 2020

Cold War Two is upon us, but it’s not all Trump’s fault (believe it or not)

Niall Ferguson on the rapid drop in temperature in US/Chinese relations in the last eight years:

President Donald Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping at the G20 Japan Summit in Osaka, 29 June, 2019.

Cropped from an official White House photo by Shealah Craighead via Wikimedia Commons.

“We are in the foothills of a Cold War.” Those were the words of Henry Kissinger when I interviewed him at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Beijing last November.

The observation in itself was not wholly startling. It had seemed obvious to me since early last year that a new Cold War — between the U.S. and China — had begun. This insight wasn’t just based on interviews with elder statesmen. Counterintuitive as it may seem, I had picked up the idea from binge-reading Chinese science fiction.

First, the history. What had started out in early 2018 as a trade war over tariffs and intellectual property theft had by the end of the year metamorphosed into a technology war over the global dominance of the Chinese company Huawei Technologies Co. in 5G network telecommunications; an ideological confrontation in response to Beijing’s treatment of the Uighur minority in China’s Xinjiang region and the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong; and an escalation of old frictions over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Nevertheless, for Kissinger, of all people, to acknowledge that we were in the opening phase of Cold War II was remarkable.

Since his first secret visit to Beijing in 1971, Kissinger has been the master-builder of that policy of U.S.-Chinese engagement which, for 45 years, was a leitmotif of U.S. foreign policy. It fundamentally altered the balance of power at the mid-point of the Cold War, to the disadvantage of the Soviet Union. It created the geopolitical conditions for China’s industrial revolution, the biggest and fastest in history. And it led, after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, to that extraordinary financial symbiosis which Moritz Schularick and I christened “Chimerica” in 2007.

How did relations between Beijing and Washington sour so quickly that even Kissinger now speaks of Cold War?

The conventional answer to that question is that President Donald Trump has swung like a wrecking ball into the “liberal international order” and that Cold War II is only one of the adverse consequences of his “America First” strategy.

Yet that view attaches too much importance to the change in U.S. foreign policy since 2016, and not enough to the change in Chinese foreign policy that came four years earlier, when Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. Future historians will discern that the decline and fall of Chimerica began in the wake of the global financial crisis, as a new Chinese leader drew the conclusion that there was no longer any need to hide the light of China’s ambition under the bushel that Deng Xiaoping had famously recommended.

May 27, 2020

Comprehensive planning and communication failures are the hallmark of Canada’s response to the Wuhan coronavirus epidemic

Chris Selley understands why the internet shaming community is dunking on the apparently large number of people who crowded into Toronto’s Trinity-Bellwoods park over the weekend but doesn’t feel the need to join them:

Screencap from a CBC report on unorganized social distancing civil disobedience at Toronto’s Trinity-Bellwoods Park on Saturday.

Human beings need to get outside and socialize. They have breaking points, and many are very understandably at them. (An aside: I can’t help noticing how many people venting fury on social media have also treated their followers to images of their back-patio office setups, or updates on their new vegetable gardens.) There is also no surplus of parkland in downtown Toronto. Photographic evidence suggests other neighbourhood greenspaces were very busy as well, though not to the same extent.

In other words, this was always going to happen. So the time is long past when politicians like Ontario Premier Doug Ford or Toronto Mayor John Tory should be able to cluck their tongues or stamp their feet at such people and expect their constituents to nod along in solidarity.

Jurisdictions facing significant COVID-19 outbreaks had one finite period of time in which to try to knock this bastard virus down. After that period of time, the socioeconomic costs of the shutdown would become unsustainable and the economy would have to reopen. We’re seeing that happen all over the world right now: in essence, countries are rolling the dice. If they did well in the allotted time, fewer people will have to die in the name of getting back to normal.

The federal, Ontario and Toronto governments have not done well — certainly not to any extent that justifies their leaders’ soaring approval ratings.

The feds have been abysmal since even before Day One, with Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam actively downplaying the threat. We shipped 16 tonnes of personal protective equipment to China with no viable plan to replace it. Whatever you think of travel bans as an anti-pandemic measure, the government undermined its own credibility by insisting they don’t work, then changing course 180 degrees over the course of a weekend. Most astonishingly, the feds at first utterly failed to communicate the most basic advice to returning travellers — advice such as “don’t stop for groceries or at the pharmacy on your way home.”

And Tam’s initial ludicrous “masks don’t work” narrative has grudgingly evolved to support the use of non-medical masks “where social distancing is not possible.” But the federal government’s official advice on “safe shopping” — indeed the entire web page titled “COVID-19 and food safety” — still doesn’t mention masks, even as the berth shoppers give each other seems to narrow by the day. This anti-mask stance seems to be ideological, bred in the bone.

April 4, 2020

The media’s grasp of modern logistics

Kurt Schlicter — who, spoiler, isn’t a fan of our news media in general — on the demands by newsbeings for the impossible to be done immediately:

We Americans are truly blessed by having a mainstream media full of brilliant renaissance men, women, and gender non-specific entities who are masters of so many varied and intermittently useful skills and who are eager to share their knowledge with us benighted souls. The pandemic has revealed that every urban Twitter blue check scribbler, MSNBCNN panelist, NYT/WaPo doofus, and barely legal “senior editor” of a website you never heard of, is a Nobel Prize-winning epidemiologist, a master logistician, and a diversity consultant to boot.

[…]

Another hitherto unknown skill that the media believes it possesses is logistics. “Why hasn’t Trump commanded a million ventilators to appear?!” the reporters demand. It’s pretty easy to see where they might have gotten the idea that the moment one articulates a desire to possess something that it magically appears. Capitalism has pretty much made that a reality. If you want something, you can go to a store and get it 24/7, or you can go on Amazon and it’ll be at your Manhattan apartment in 48 hours. Since they have never built anything or transported anything or distributed anything, only benefited from the labor of the unhip people who do those things, it’s only natural that the delayed adolescents who make up our media class imagine that material goods can be simply wished into being. After all, for all practical purposes during normal times, because of the efforts of Americans they look down upon, material goods pretty much can be simply wished into being. But prosperity takes work, not that the media would know.

[…]

Apparently, the media class thinks there are giant warehouses with an endless supply of goods just sitting there, somewhere, waiting. They have no idea about how logistics work, how goods flow quickly from producer to market and how expected resupply levels need a few days to adjust from a 10 percent daily turnover to a 30 percent daily turnover. They have zero appreciation for inventory management because no one they know does unglamorous stuff like that.

It’s all much easier in a socialist command economy. You get nothing and like it. Or don’t like it. Whatever. Here’s your weekly bean allowance. Workers of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but access to toothpaste and toilet paper.

The best part is when the media – the same media that was collectively soiling its Dockers because that mean old Trump was barring direct flights from China because of racism and stuff – demands to know why, back in December, Trump was not commanding a zillion Wuhan Flu tests, a zillion masks, and a zillion ventilators be created, while locking down all of America. Leaving aside the whole lack of an enumerated power to do that thing, in what world would have Trump have convinced anyone – least of all the media that was slobbering over his bogus impeachment at the time – that some bat soup-derived pathogen in BumFoo, China, was going to black swan all over America’s economy? The lack of seriousness by the people who presume to be reporting the news to us is more breathtaking than the damn ChiCom grippe.

February 24, 2020

Canadian-American relations (and Canadian foreign relations in general) in the 21st century

Ted Campbell looks at the undisputable fact that Canada barely matters in Washington DC, and that this has been true since the end of the first Bush administration. He discusses a recent Globe and Mail article by David Mulroney which examines the need for the Canadian government to formally rethink “Canada’s role in the world” in that light:

Justin Trudeau meets with President Donald Trump at the White House, 13 February, 2017.

Photo from the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

Mr Mulroney sees two major problems that confront Canada fifty years after A Foreign Policy for Canadians was published:

- First, he says, “Canada is again dealing with a threat to our autonomy from a major power, but this time, it comes not from the United States, but from the new world that was coming into being 50 years ago. The threat is now China, which is using its economic power to influence and silence us, is undermining our national security, and is challenging the rules-based international system that the review itself championed;” and

- Second, “we again need to face up to the consequences of our diminished status, but this time much closer to home. Fifty years on, the problem isn’t that the United States wants to dominate us, but that it has largely forgotten us. While it is tempting to blame this on the chaos of the Trump era, the painful reality is that the relationship has been in decline for some time, something that was manifestly evident in the cool detachment that marked Barack Obama’s management of relations with Canada.”

I think that second is, actually, more serious than the first. I believe we can wrap our collective mind around the fact that China doesn’t like us, that it regards us as an irritant and that it is using us as a whipping boy to send a message to its other, more important, trading partners. What has been harder to grasp is that Ameria no longer cares. It isn’t just Donald Trump, it was even just Barack Obama. George W Bush didn’t care either. Despite the great debates in Canada, it seems clear that President Bush never even asked for our help in either Afghanistan or Iraq, the “pressure” to do something to stand with the USA was entirely self-generated within Canada’s own foreign affairs and defence establishments. Bush, Chaney, Rumsfeld and Myers (the latter was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 2001 to 2005) were, possibly, grateful for the help on the ground, when they noticed it at all, but quite uninterested in Canada’s views on any of the issues concerned. Nor did Bill Clinton care about our views on or our actions in e.g. the Balkans. We, as a country, and our leaders, Jean Chrétien, Paul Martin, Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau, did not and do not count for anything in Washington. Neither Chrystia Freeland nor Erin O’Toole nor any other Canadian prime minister, Conservative or Liberal, will fare any better. The last time Canada mattered was when Brian Mulroney and George H W Bush renegotiated the Canada-US Free Trade deal, making it into NAFTA, over a quarter-century ago. And the end of the halcyon days of Canada-US relations came a full decade before that, in the Mulroney-Reagan years. That can only change if Canada makes itself matter.

[…]

We, Canadians, must accept ~ and millions will not want to accept this ~ that, as Mr Mulroney says, “International influence … [and that includes influence where it counts most, with the USA] … is enabled by a strong economy, robust national infrastructure and institutions, and the willingness to invest in national defence and security.” One of the impacts of Pierre Trudeau’s policies was to divert spending from National Defence to social spending. That was immensely popular with many, actually with most Canadians … something for (a perceived) nothing always is. None of Brian Mulroney, Paul Martin or Stephen Harper, all of whom, it seemed to me, wanted to reverse course and act responsibly were able to change what Pierre Trudeau had put in place. The political price was suicide. But it has been fifty years and Canada is at risk of being totally irrelevant in an increasingly complex and dangerous world.

David Mulroney’s second challenge ~ recovering “the confident elaboration of national identity,” is, I suspect, much more difficult, especially given the “post-national state” quasi-intellectual rubbish that Justin Trudeau says was part of “his father’s vision.” It’s lunacy, of course, but it’s the sort of lunacy that appealed to many in the 1960s and appeals, again, a half-century later.

While I don’t disagree with Mr. Campbell’s analysis (and that of David Mulroney), I think getting our domestic house in order is the top priority, and the current Trudeau government does not appear to be doing much constructive on that sheaf of issues. With the very rule of law threatened at home, there’s little to no point in casting our eyes across the 49th parallel or overseas: we need to address the breakdown of internal governance first.

November 27, 2019

The Deep State versus the President

David P. Goldman reviews a new book by Andrew McCarthy on the ongoing conflict between the elected President of the United States and the permanent bureaucracy:

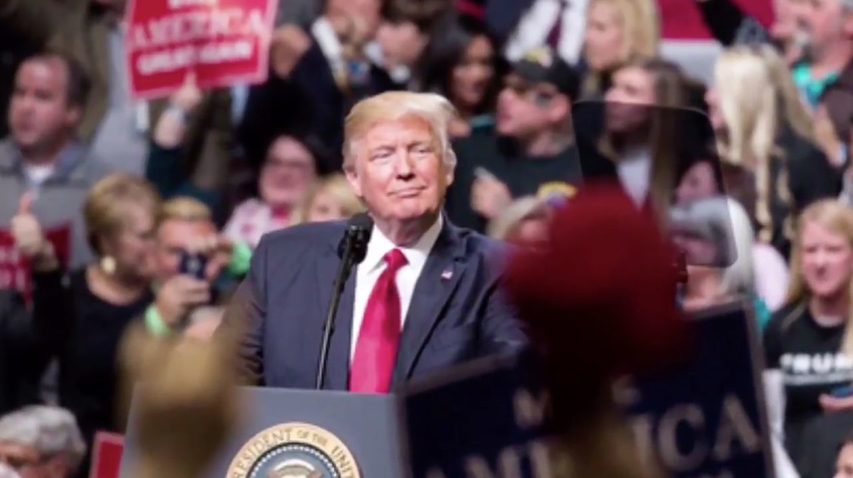

Donald Trump addresses a rally in Nashville, TN in March 2017.

Photo released by the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

America’s Central Intelligence Agency in concert with foreign intelligence services manufactured the myth of Donald Trump’s alleged collusion with Russia, argues Andrew McCarthy, a distinguished federal prosecutor turned public intellectual.

A contributor to Fox News and a prolific writer for The National Review and other conservative media, McCarthy well knows how to build a case and argue it before a jury. His latest book Ball of Collusion should be read carefully by everyone with an interest in American politics. It is exhaustively documented and brilliantly argued, and brings a wealth of evidence to bear on behalf of his thesis that an insular, self-perpetuating Establishment conspired to sandbag an outsider who threatened its perspectives and perquisites.

From my vantage point as an American, the constitutional issue is paramount: The American people elected Donald Trump, and it is horrifying to consider the possibility that a cabal of unelected civil servants supported by the mainstream media might nullify a presidential election. That is why I support the president unequivocally and without hesitation against his detractors.

But this sordid business has deep implications for America’s allies as well as her rivals. Trump is not a popular president overseas, except in Poland, Hungary, and Israel. In the eyes of polite opinion, McCarthy writes, “Donald Trump was anathema: a know-nothing narcissist – as uncouth as Queens – riding a populist-nationalist wave of fellow yahoos that threatened their tidy, multilateral post-World War II order.” China (and not only China) views Trump as a bully who presses American advantage at the risk of disruption to the global economy.

Donald Trump has one quality for which the rest of the world should be grateful: He really does not care how China, Russia, or any other country manages its affairs. By “America First,” he simply means that he cares about what happens in America, and is incurious about what happens outside America unless it affects his country directly. That stands in sharp contrast to view of all the wings of America’s political Establishment – progressive, “realist” and neoconservative – who believe that America should bring about the millenarian End of History by bringing democracy to Iraq and Afghanistan, by expanding NATO into a giant social-engineering project, by pressing China to transform itself into a Western-style democracy, and so forth.

McCarthy reports in persuasive detail how the spooks set up the president. There is more to be said, though, about why they did it. I will summarize McCarthy’s findings, and afterward discuss the motivation.

October 6, 2019

Finally a reason to climb on the impeachment bandwagon

Andrew Heaton, in his latest newsletter, explains why he’s finally come down on the side of impeaching President Trump:

Okay, here’s the main thing I wanted to talk to you about: America is about to slap a TWENTY-FIVE PERCENT tariff on scotch. The underlying story involves the WTO and Airbus, but I think I can save everybody a lot of time by pointing out that our president is a mouthbreathing protectionist who’s too lazy to read Adam Smith’s wikipedia page.

Here are a few things to consider:

- Tariffs are just taxes, designed to punish you for having the gall to buy something from a foreigner.

- This will hurt Scottish distillers, and potentially price out distillers with low profit margins.

- I might have to switch to wine on dates.

- We have now spent more money needlessly bailing out farmers from a trade war with China than we did bailing out banks under Bush.

- We’ve known about the idiocy of tariffs since The Wealth of Nations came out in 1776.

- Trump, a man lacking an ideological core, for reasons which boggle the mind, seems to genuinely believe tariffs and protectionism are good things, as he has maintained since the 80s.

Chances are if you subscribe to this newsletter you’re not a teetotaler, but on the off chance you are, allow me to make a case against whisky taxes even if you are not personally apoplectic about a tax hike on Laphroaig. (A concoction personally invented by Almighty God. It’s like you’re drinking a campfire. Try it.)

There’s an old saying: when goods don’t cross borders, armies do. I concur with this. In fact my largest contribution to the field of economics (Nobel Prize forthcoming) is Heaton’s Peace Through International Mistresses Theory.My groundbreaking idea is that we want to have an interconnected, global economy with lots of transnational trade, because businessmen will be less supportive of bombing cities their mistresses live in. When trade wars happen, international trade collapses, and suddenly businessmen are flying to Berlin and Paris a lot less. Pretty soon we’re firebombing Tokyo.

It would probably be more appropriate of me to dedicate my political analysis to the forthcoming Ukraine/Trump/Biden/Impeachment circus which will dominate our lives for the next few months. However in my case I don’t need to. The president has messed with my scotch. Now it’s personal. I’m all in.

Impeach the guy.

#FreeTrade

You can subscribe to Andrew’s email newsletter here.

July 9, 2019

QotD: Tariffs

The entire aim of having trade is so that we can go buy those lovely things made by foreigners. We only export so as to be able to swap something for those foreign made goods. Thus tariffs are a bad idea to begin with — why should we tax ourselves for gaining access to the very point of our having trade in the first place? Sadly all too many don’t grasp this point. Too many of them being in the current Trump Administration.

Over and above the general point that we don’t want to limit trade nor imports there’s another worry with tariffs and trade wars. Which is what the International Monetary Fund is complaining about. The imposition of more tariffs is a disruption to that global economy. One that is going to reduce growth, the very thing we all desire.

Tim Worstall, “IMF Says The U.S. And China Trade Tariffs Are A Major Risk To World Growth”, Seeking Alpha, 2019-06-07.

July 4, 2019

Is there a country with which Justin Trudeau hasn’t messed up Canada’s relationship?

Ted Campbell responds at some length to a Globe and Mail article by Doug Saunders, outlining the degradation of diplomatic relations with almost all our allies and trading partners since Justin Trudeau became PM.

The Globe and Mail‘s award-winning international affairs correspondent Doug Saunders, someone with whom I (almost equally) often disagree and agree, has penned an insightful piece in the Good Grey Globe in which he says that “Suddenly, Canada finds itself almost alone in the world, with a Liberal government realizing that its optimistic foreign policy no longer entirely makes sense … [but, he concludes] … Even if the current crisis in liberal democracy proves temporary and short-lived, we know that it can recur – and likely will. If the institutions of 1945 no longer work and the doctrines of 2015 have failed to have an effect, we should develop new ones that will keep Canada connected to the better parts of the world for the rest of the century.”

[…]“After the Second World War,” Mr Saunders writes, “Canada gained a few more foreign-policy outlets. Canada played a large role in creating the institutions that governed the postwar peace: the United Nations and its various organizations; NATO; the global trade body that became the World Trade Organization; the Bretton Woods institutions, including the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Canada was decisive in the international agreement that authorized the future creation of the twin states of Israel and Palestine, giving it a role in the Middle East that expanded with its creation of the institution of peacekeeping after the Suez Crisis in 1956 … [but this really is a silly statement, albeit one that too many Canadians believe to be true. Canada didn’t create the “institution of peacekeeping” in 1956. It was already there, in the United Nation’s case since Ralph Bunch (USA) and Sir Brian Urquhart (UK) created it in 1948 and it had been around since, at least, Woodrow Wilson’s 14 Points speech in 1918, but it is now part of the Laurentian Elite‘s quite dishonest revisions of Mike Pearson’s sterling legacy as a diplomat and politician] … And, starting in the 1950s, Canada became a player and a spender in the new field of foreign aid and development. Under both Liberal and Progressive Conservative governments, Canada used those tools to play a small but well-regarded place in the liberal-democratic order – and to slowly but profitably build its trade and economic relations.”

[…]

I agree with Doug Saunders about the sources of Canada’s current weakness. He neglected to mention the root cause: Pierre Trudeau explicitly rejected, in the late 1960s, the “St Laurent Doctrine” and replaced it with a social “culture of entitlement” which meant that our place in the world had to be sacrificed on the altar of a reinforced social safety net. I agree that Donald J Trump is the key to our and the West’s current angst and confusion, not Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping or Arab terrorists, all of whom are easier to understand, but I would argue that we would be much better placed to cope with president trump and the 21st century had we not abandoned our role as a leading middle power circa 1970. I have reservations about all three of Mr Saunder’s prescriptions:

- I’m not sure another G-N, not even a “committee to save the world” is a really good idea;

- I am nervous about interfering in the internal affairs of other countries ~ think about “do unto others” and all that; and

- I really doubt that Canadians are ready to spend what’s needed on our defence and, I suspect, they will not be until it is (almost) too late.

Like Mr Saunders, Mr Lang and Professor Paris, I, too, want to save the liberal world order and Canada’s place in it; I’m just not sure that any of the proposed solutions offered by Doug Saunders, by Eugene Lang or even by Professor Roland Paris are going to be enough. I think we need less formality and fewer organizations in international actions and a lot more ad hocery. I hope that we will have new, adult leadership here in Canada in the fall of 2019 and I hope that a new, grownup prime minister will begin, quickly, to mend relations with Australia, India, Japan and the Philippines and other Asian nations, to shore up our relations with Europe and, especially, with Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and UK. I also hope Canada will open new, more productive dialogues with Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America and with Iran, Russia and China, also. I am convinced that Professor Stein is correct and we must have an “interests-based,” even a selfish suite of foreign, defence, immigration and trade policies. We should not go about looking for enemies, but we must understand that we have precious few friends and, for now, we cannot count on America to be one of them. America, Australia and Britain, China, Denmark and India, Japan, Mexico and the Philippines, and Singapore and Senegal, too, will all act in pursuit of their own interests; Canada needs to be willing and able to do the same and to work with them, even with Donald Trump’s America and Xi Jinping’s China and Vladimir Putin’s Russia when our interests converge and, politely, stand aside when they diverge. The G7 and G20 and a proposed new G9 are all harmless, but also, largely useless, talking shops. Both diplomacy and foreign affairs must be conducted on a case-by-case, country-by-country, issue-by-issue and interest-by-interest basis and diplomacy and foreign affairs can only be conducted with positive effect when Canada is respected for both its examples and values (soft power) and for its hard, economic and military power, too.

Thus, the first step in doing our part to “save the world” is probably the one that most Canadians will have near the bottom of their priority list: rebuilding Canada’s military ~ which must start, after a lot of the fat has been trimmed from a morbidly obese military command and control (C²) superstructure, with steadily growing the defence budget … and that cannot happen until the economy is firing on all cylinders, including energy exports to the world.

June 23, 2019

The state of play in the Strait of Hormuz

Arthur Chrenkoff wonders what would happen if Iran gave a war, but nobody came:

A satellite view of the Strait of Hormuz, 30 December 2001.

Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC via Wikimedia Commons.

Nearly twenty per cent of world crude oil shipments (from the Arab Gulf producers) go out to the rest of the world through the Strait of Hormuz, which Iran is threatening to close (hence its recent attacks on oil tankers).

However, through a combination of fracking, increased mainline well production and greater efficiencies, the United States is now finally energy self-sufficient. For all that America cares, Iran could cut off all the traffic through the Strait and it would have a minimal impact on the domestic economy, some minor logistical adjustments aside.

Nearly two thirds of the oil that travels through the Strait ships to Asia instead, and specifically to China, India, Japan and Korea, which are significantly more dependent on that oil to power their energy-hungry, export-oriented economies than other regions of the world.

China, notably, has been Iran’s tacit international ally. If Iran wants to interfere with the free navigation in its backyard and in so doing antagonise one of its few remaining backers, it should be left alone to do so.

These circumstances – the US doesn’t need the Gulf oil, China does – should convince the United States to stand back and not involve itself yet another time as the world sheriff to enforce the rules of international law and maintain the open international trading system. The rest of the world all too often free-rides on America’s good graces (not to mention its blood and treasure), while at the same time reserving the right to castigate the superpower for its interventionism. Why not let the world experience what it’s like without having the US solve all their problems (while getting all their blame)? Maybe the European Union or the United Nations can do something [canned laughter]. Or maybe the most affected Asian nations can try to solve their own oil supply problems. Good luck, lads.