Chris Bray has had to visit a large urban hospital frequently in the last little while and he’s noticed just how readily some people have adapted to the pandemic world situation:

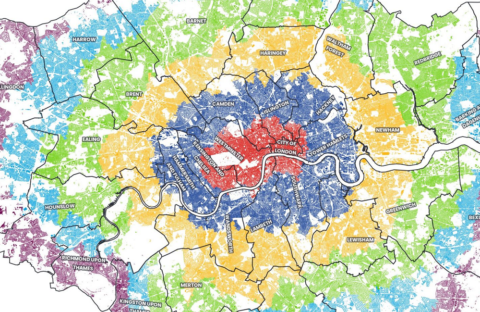

Observers of the Soviet Union noted the presence of Homo Sovieticus, the species adapted to the culture: “a double-thinking, suspicious and fearful conformist with no morality”. It seems fairly clear that the Blue Zones are birthing a version of this creature, well accustomed to a life centered on compliance rituals and the production of the Required Documents™.

But Soviet subjects usually found a layered response to the compliance culture, with backdoor deals and systems of baksheesh. Factories and offices evolved a set of people who learned the skills of a fixer, greasing supply chains and easing problems with a little something for your family. I just happen to have a couple of extra cartons of cigarettes, friend, and about that delayed shipment of ball bearings …

So one of the things that’s interesting about Large Urban Hospital, where the rules are the rules and I’m sorry, sir, that’s our policy, is that the rules aren’t entirely the rules, and the luck of the personnel draw sets your course. I already know the helpful front desk check-in staff — Hi, welcome back! — and I already know which one scowls at the computer, and asks if you’re sure you cleared your visit in advance, and says she’s going to need to make a few phone calls to check on your paperwork, and I need to see those test results again (she says, pulling on her scowling at documents glasses). Checking in at the lobby desk can take thirty seconds, or it can take ten minutes; it can be miserable and hostile, or it can be relatively pleasant and human. But in both cases, the person behind the computer, and the people who put them there and provide them with the systems that govern their work, believe that the work is standardized, and everyone at the check-in desk is enforcing the rules.

We have literally insane systems of ritual behavior, but within those systems we have people who are still people, and people who have very much embraced the compliance behaviors. There are dehumanizing institutions, and holy shit are there people who like it.