World War Two

Published 17 Jun 2023Japanese and American navies are heading for a showdown in the Philippine Sea, even as American forces land on Saipan in the Marianas in force. The Japanese have Changsha under siege in China, the Allies advance in both Normandy and Italy, the Soviets advance in Finland, and the massive Soviet summer operation is coming together and will begin in a matter of days.

(more…)

June 18, 2023

Titanic Clash Looms In Pacific – WW2 – Week 251 – June 17, 1944

June 17, 2023

China’s long-term revenge for the Opium Wars

In Quillette, Aaron Sarin discusses what he calls the “Reverse Opium War” with Chinese drugs flooding the US street drug culture:

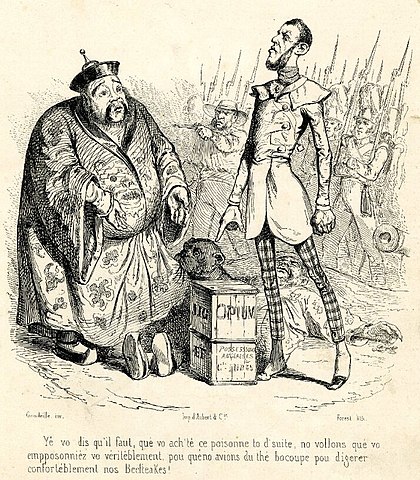

Jean-Jacques Grandville cartoon originally published in Charivari in 1840. “I tell you to immediately buy the gift here. We want you to poison yourself completely, because we need a lot of tea in order to digest our beefsteaks.”

Image and translated caption from Wikimedia Commons.

An epidemic is stalking American cities. Every day, men and women die on sidewalks, in bus shelters, on park benches. Some die sprawled in crowded plazas at midday; others die slumped in the corners of lonely gas station bathrooms. Internally, however, the circumstances are the same. They all end their lives swimming in the warm amniotic dream of a lethally dangerous opioid. When it comes, the moment of death is imperceptible: coaxed by the drug further and further from shore, the user simply floats out too far, passing some unmarked point of no return. The heartbeat weakens, the breathing slows and shallows. As soft an end as anyone might wish for.

This is the fentanyl crisis. It may seem strange to connect a very modern and very American phenomenon to a brace of wars waged 200 years ago by the British Empire on the last of the Chinese dynasties. But so the rhetoric runs: we are witnessing a Reverse Opium War; a belated Sinic revenge.

The Communist Party teaches schoolchildren that China was once a glorious superpower, until it was brought low by that subtlest and most devious of British weapons: Lachryma papaveris (poppy tears). Opium sapped the nation’s strength, and when the Chinese authorities banned it, then Britain went to war — twice.

Those wars crippled the Qing and heralded a “century of humiliation” for China — multiple military defeats and lopsided treaties, the Anglo-French looting and burning of the Emperor’s Summer Palace, the Japanese Rape of Nanking and lethal human experimentation by Unit 731 — ending only with the liberating forces of Marxism-Leninism in 1949. Now some commentators are telling us that history has inverted, that karma has kicked in.

Before examining this idea, we should remind ourselves of the American predicament. Ten years ago, fentanyl began its steady flow from China to the United States. Within just three years the drug had surpassed heroin to become the most frequent cause of American overdose deaths. Fentanyl is many times more powerful than heroin, and so there should be no surprise that lethality has spiked since the great Chinese flow began: in 2012, heroin topped the list with 6,155 deaths; by 2016, fentanyl was proving three times as deadly, with 18,335 deaths. The opioid’s influence seeps into all corners of the narcotics market, due to dealers hiding it in cocaine, heroin, and ecstasy. And it leaks across social strata, killing the homeless but also the rock star Prince, who passed away in an elevator at his Paisley Park estate after ingesting fentanyl disguised as Vicodin.

Under American pressure, the Chinese authorities agreed to regulate fentanyl analogs and two fentanyl precursor chemicals, but it soon turned out that shipments were being rerouted via Mexico. With this new arrangement, the crisis only deepened: between 2019 and 2021, the opioid killed 200 Americans a day. Last year alone, the DEA seized quantities of the drug equivalent to 410 million lethal doses. That’s enough to kill everyone in the US. Even a pandemic couldn’t stem the flow for long: in fact, Wuhan is one of the world’s most reliable suppliers of fentanyl precursors (a role it played both before and after starring at the eye of the COVID storm).

The booming fentanyl trade does not appear to rely on traditional criminal organisations, in the way that East Asian methamphetamine trafficking depends on the Triads. Instead, it turns out to be small family-based groups and legitimate businesses who manufacture and move the drug. Usually located on China’s south-eastern seaboard — Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong — these groups use the cover of the vast Chinese chemical industry to channel ingredients into the manufacture of fentanyl-class drugs and their precursors.

June 16, 2023

June 12, 2023

It’s an insult to Chuck Barris and The Gong Show to compare it to the Justin Trudeau Show

In the weekly dispatch from The Line, the editors defend the honour of the original Gong Show and say that it’s not fair or right to compare that relatively staid and dignified TV show to the Canadian government’s performance art on the foreign interference file:

When the news broke late Friday afternoon that David Johnston was resigning from his position as special rapporteur on Chinese interference, the general reaction across the chattering class was a variable admixture of amusement and scorn. There’s probably a German word for it, but the security and intelligence expert Wesley Wark captured the tone of it with the headline on his Substack post, which said, simply: “Gong Show“.

We’re somewhat inclined to concur with Wark, except the three-ring train wreck that has marked Johnston’s time as Justin Trudeau’s moral merkin has been so disastrous that we think apologies are due to Chuck Barris, in light of the relative sobriety of his famous game show.

Reporters at the Globe and Mail and Global News started breaking stories about Chinese interference in Canadian elections a few months back, based largely on leaks from inside the Canadian intelligence apparatus. Almost immediately it was clear that the Liberals had a major problem on their hands, one that was going to require levels of transparency, good judgment and political even-handedness that this government has manifestly failed to achieve during its almost eight years in power.

Yet when Trudeau announced that he was going to appoint an “eminent Canadian” as “special rapporteur” to do an investigation and report back to the government with recommendations for how it should tackle the issue, we gave a collective groan here at The Line. Given the endless similar tasking of retired Supremes passim, it was clear that the pool from which Trudeau was going to fish his eminent personage was very shallow, and pretty well-drained. Indeed, at least one of us here was willing to bet large sums that it would be David Johnston.

What do we make of all this? Here’s the situation as we see it, in bullet form for brevity’s sake:

- Johnston should never have been offered the position of special rapporteur

- Having been offered the job of special rapporteur, Johnston should never have accepted it

And that is basically it. But given that Trudeau had the poor judgment to ask him, and Johnston had the poor judgment to accept, we think everything that has happened since was pretty much inevitable. We couldn’t have guessed at all the details of how this would have played out, especially the delicious elements beginning with the decision to hire Navigator to provide strategic advice (to manage what, exactly?), the revelation that Navigator had also provided strategic advice to Han Dong (who, recall, Johnston more or less exonerated), the firing of Navigator and the involvement of Don Guy and Brian Topp … this is really just gongs piled upon gongs piled upon gongs.

But the overall trajectory of Johnston’s time as special rapporteur? If you had told us ahead of time that this was more or less how things would go, we wouldn’t have been much surprised. Why? Because we live in Canada. And this is how Canada’s governing class behaves. It is a small, incestuous, highly conflicted and enormously self-satisfied group of people that is so isolated from the rest of the country they don’t even realize how isolated they are.

Honestly. What in heaven’s name gave Trudeau the idea that it would be smart to ask a former governor general to help launder his government’s reputation? And why on Earth did Johnston think it was a good idea to accept? Forget the Navigator stuff, this turkey was never going to fly. Johnston’s report was not accepted as the wise counsel of a wise man; instead it was seen as a partisan favour by a conflicted confidant. Sure, Johnston was subject to some pretty unfair attacks from the opposition, but what did he think was going to happen? Has he paid any attention over the last decade? But pride is a form of stubborness, and even after parliament voted for him to go, Johnston insisted he would stay on to finish his work. Until, on Friday afternoon, he decided he would not.

We’re not going to speculate about why Johnston finally pulled the chute. We’d like to think that the former GG in him thought it best to obey the will of the House of Commons. We rather hope it had nothing to do with some pointed (and unanswered) questions put to Johnston’s office by the Globe and Mail, asking whether Navigator had been given a heads-up on Johnston’s conclusions on the Dong file.

Maybe it doesn’t matter. As Paul Wells put it in a recent column, Trudeau sought to “outsource his credibility by subcontracting his judgment,” where credibility was supposed to flow from Johnston to Trudeau. Instead, and we would say, inevitably, the flow went in the opposite direction. If the prime minister had any credibility to lead the country on this issue, he wouldn’t need a special rapporteur in the first place. The fact that Trudeau felt the need to appoint one is a tacit admission that he knows he doesn’t have the trust of the people.

And that is the real problem here. The Johnston saga has ended where it was always going to, with a once-honorable man’s reputation in tatters and the problem he was brought in to address still unresolved. David Johnston has resigned, as he must have. In our view, that’s one resignation too few.

June 11, 2023

The Invasion of Normandy begins! – WW2 – Week 250 – June 10, 1944

World War Two

Published 10 Jun 2023The Allies’ gigantic amphibious invasion of France begins and by the end of the week they’ve carved out a decent-sized beachhead. Meanwhile in Italy the Allied advance takes Rome. The Soviets are launching new attacks of their own — now against the Finns, and the Japanese at Kohima … have just plain had enough.

(more…)

June 10, 2023

Do you also dream of apocalypse?

John Psmith certainly does, as he explains before plunging into a review of a book on Chinese warfare between 300 and 900 AD:

I have a secret confession to make. Late at night, when Mrs. Psmith and the Psmithlets are all tucked away in their beds, I like to stay up in my study and fantasize about … the end of the world. But not just any end of the world, because most apocalypses are very boring. For example: “AI unleashes killer nanobots that turn everybody into paperclips.” Yawn. How dull. Where’s the drama in that? No, like all disordered fantasies, mine are fun, and ever-so-conveniently constructed to push the bounds of plausibility while still being technically possible. I’m mostly fantasizing about apocalypses where almost everybody dies, but where one dashing and well-prepared man with pluck and determination and a giant pile of book reviews can restore an island of order and civilization. Hey come on, it could happen!

Most apocalypses would be awful — we would all die instantly, or else we would all die slowly and painfully, but somewhere perfectly balanced in the middle are the apocalypses that would be very exciting, and those are the emotional driver that lead me to engage in a mild degree of prepping. Now like all potential addicts, I have some hard and fast rules, clear lines that prevent me from spending all my family’s savings on refurbishing an old missile silo. My main rule is that any prepping I do has to have a dual use in some less exciting but more likely scenario.

So I store a lot of water in my basement because, look the US government tells me it could be useful in the event of a regional or local disaster. We have emergency bags pre-packed that include a list of rendezvous locations a day’s walk from our house because, hey, there are all kinds of reasons we might need that, okay? I own this tool so I can shut off my gas in the event of an earthquake and totally not because it looks handy for bludgeoning feral packs of marauders, so stop judging me. I have precious metals buried in the ground in a secret location because, uhhh … it’s good to have a tail-risk hedge in your portfolio, all right? What’s that? Why is there ammo in there too? Look, a good portfolio should be anti-fragile …

I think all of this is why I like Chinese history so much, because it’s just way crazier, bloodier, and more apocalyptic than the history of most other places. In Western Europe civilization collapsed once (okay fine, twice (okay, fine, three times)), and we’re still ruminating over it and working through this unending cultural psychodrama like some civilization-scale therapy addict. Meanwhile, in China, civilization collapsing is like Tuesday. The history of China is an endless cycle of mini-apocalypses in which the entire political, economic and moral order gets razed to the ground and Mad Max conditions prevail for a few decades or centuries, until somebody gathers enough power in his hands to establish a new dynasty and all is peaceful and harmonious under heaven. A few hundred years later, that new regime grows tired and old, the Mandate of Heaven slips away, and the cycle repeats.

George MacDonald Fraser – Quartered Safe Out Here

We Have Ways of Making You Talk

Published 16 Jan 2023Merry Christmas from “We Have Ways of Making You Talk”. Over the next 12 days Al and James are reading extracts from some of their favourite books about the Second World War. Today Al is reading from Quartered Safe Out Here, by George MacDonald Fraser.

(more…)

June 6, 2023

QotD: “A second front” in 1942

I have been reading the recent biography of the British CIGS Alanbrooke, and been struck by the clear and concise explanation of the differences between the British and Americans over the “second front” in Europe, and when it could be.

[…]

A plan put together for the incredibly unlikely event of sudden German collapse, was Sledgehammer. This was the understanding of Sledgehammer adopted by most Americans. A very limited offensive by very inadequate forces, which could only succeed had Germany already gone close to collapse. Given the circumstances this was somewhat delusional, but it never hurts to plan for eventualities, and the British were happy to go along with this sort of plan.

[…]

Any attempt at Sledgehammer would of course have failed. The German army had not yet been bled dry on the Eastern front, and the Luftwaffe was still a terrifying force which could be (and regularly was) easily moved from Russian mud to Mediterranean sunshine and back again in mere weeks. Even ignoring the opposition, the British were gloomily aware that the Americans had not a clue of the complexities of such a huge amphibious operation. At the time of discussion – May 1942 – the British were using their first ever Landing Ship Tanks and troopships equipped with landing craft to launch a brigade-size pre-emptive operation against the Vichy French on Madagascar. (Another move many historians think was useless. But coming only months after the Vichy had invited the Japanese into Indo-China – fatally undermining the defenses of Malaya – and the Germans into Syria, it was probably a very sensible precaution. Certainly Japanese submarines based in Madagascar [could] have finally caused the allies to lose the war at sea!)

The British deployed two modern aircraft carriers, and a fleet of battleships, cruisers, destroyers and escorts and a large number of support ships, on this relatively small operation. It was the first proper combined arms amphibious operation of the war, and was very helpful to the British to reveal the scale of amphibious transport needed for future operations. By contrast the US Marines hit Guadalcanal six months later from similar light landing craft, and with virtually the same Great War-vintage helmets and guns that the ANZACS had used at Gallipoli. Anyone who reads the details of the months of hanging on by the fingernails at Guadalcanal against very under-resourced Japanese troops, will be very grateful that the same troops did not have to face veteran German Panzer divisions for several years.

So I do not know of any serious historian who imagines that an invasion of France in 1942 could have led to anything except disaster. There are no serious generals who thought it either. (Only Marshall and his “yes-man” Eisenhower consistently argued that it might be possible. And Eisenhower later came to realise – when he was in charge of his third or fourth such difficult operation – that his boss was completely delusional in his underestimation of the difficulties involved. See Dear General: Eisenhower’s Wartime Letters to Marshall for Eisenhower’s belated attempts to quash Marshalls tactical ignorance about parachute drops and dispersed landings for D-Day.)

In practice no matter how much Marshall pushed for it, only British troops were availabe for such a sacrificial gesture, and the British were not unnaturally reluctant to throw away a dozen carefully nurtured and irreplaceable divisions on a “forlorn hope”, when they would prefer to save them for a real and practical invasion … when circumstances changed enough to make it possible.

Unfortunately Roosevelt told the Soviet foreign minister Molotov that “we expect the formation of a second front this year”, without asking even Marshall, let alone wihtout consulting his British allies who would have to do it with virtually no American involvement. The British Chiefs of Staff only had to show Churchill the limited numbers of landing craft that could be available, and the limited number of troops and tanks they could carry, to make it clear that this was ridiculous. Clearly this stupidity was just another example of Roosevelt saying stupid things without asking anyone (like “unconditional surrender”) that did so much to embitter staff relations during the war, and internationaly relations postwar. But it seems likely that the British refusal to even consider such nonsense was taken by Marshall and Stimson as a sample of the British being duplicitous about “examining planning options”.

The British fixed on a “compromise” to pretend that a “second front” could be possible. North Africa, could be conquered without prohibitive losses. It was not ideal, and in practical terms not even very useful. But it might satisfy the Americans and the Russians. Nothing else could.

Marshall in particular spent the rest of the war believing that when the British assessment clearly demonstrated that action in Europe was impractical and impossible, they had just been prevaricating to get what they always intended: operations in the Med. In some ways he was correct. The British had done the studies on France despite thinking that it was unlikely they would be practical, and were proved right. Marshall and Eisenhower had just deluded themselves into thinking an invasion might be practical, and could not accept that there was not a shred of evidence in favour of their delusion.

Nigel Davies, “The ‘Invasion of France in 1943’ lunacy”, rethinking history, 2021-06-21.

June 4, 2023

The Allies are Driving for Rome – WW2 – Week 249 – June 3, 1944

World War Two

Published 3 Jun 2023The Allies head north in Italy after the fall of Monte Cassino last week; the Japanese head south in China in a new phase of their offensive; and the Soviets and the Western Allies make ever more concrete plans for their huge offensives, to go off very soon.

(more…)

June 2, 2023

“Montgomery was a military talent; Slim was a military genius”

Dr. Robert Lyman is a known fan of Field Marshal Slim (as am I, for the record), not only for his brilliant military achievements, but also as a writer:

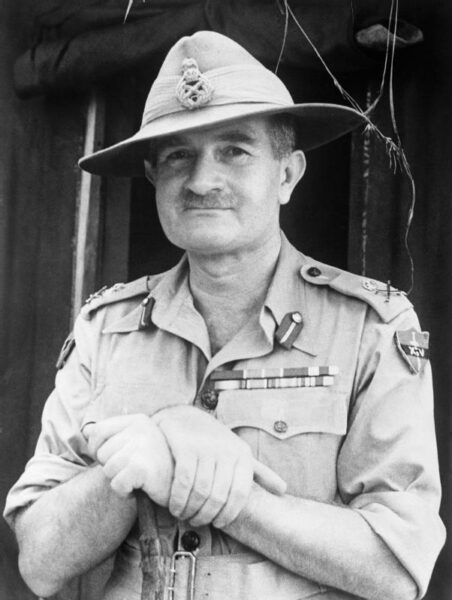

Field Marshal Sir William Slim (1891-1970), during his time as GOC XIVth Army.

Portrait by No. 9 Army Film & Photographic Unit via Wikimedia Commons.

How many British generals have been able to write as well as they could fight? Strangely perhaps, quite a few. Field Marshal Sir Michael Carver (Dilemmas of the Desert War, The Seven Ages of the British Army), General Sir David Fraser (And We Shall Shock Them), General Sir John Hackett (The Third World War) and Major General John Strawson (Beggars in Red) are four outstanding soldier-writers that spring immediately to mind. Even Monty wrote his memoirs. And in our own day I’ve read plenty of competent books from a slew of men who’ve reached the top of the profession of arms. The work of some, like that of General Sir Richard Sherriff (2017: War with Russia), Major General Mungo Melvin (Manstein) and Brigadier Allan Mallinson (Too Important for the Generals et al), could be described as outstanding. Julian Thompson and Richard Dannatt also fit this bill. But by far and away the best of Britain’s soldier-writers in the last century was also probably the greatest soldier – and field commander – of them all: Bill Slim. He was, more properly, Field Marshal William J. Slim KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC, KStJ, the onetime General Officer Commanding the famous 14th Army – the so-called Forgotten Army – of Burma fame. He was, in this author’s view, the greatest British general of the last war (to avoid further debate, let’s just agree that Monty failed as a coalition commander, whereas Slim excelled). Slim’s ability as a general is perfectly summed up by the historian Frank McLynn:

Slim’s encirclement of the Japanese on the Irrawaddy deserves to rank with the great military achievements of all time – Alexander at Gaugamela in 331 BC, Hannibal at Cannae (216 BC), Julius Caesar at Alesia (58 BC), the Mongol general Subudei at Mohi (1241) or Napoleon at Austerlitz (1805). The often made – but actually ludicrous – comparison between Montgomery and Slim is relevant here … there is no Montgomery equivalent of the Irrawaddy campaign … Montgomery was a military talent; Slim was a military genius.1

Some hint of Bill Slim’s fluency with the written word to complement his ability as a soldier came with the publication of Defeat into Victory in 1956, his superb retelling of the Burma story. Apart from its remarkable tale – the humiliation of British Arms in 1942 eventually overturned by a triumphant (and largely Indian) army in 1945 (87% of Slim’s army was Indian) – the quality of the writing was astonishing. Its author, a man who would be appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1949 (following Monty), the first Sepoy General ever to do so, and by Attlee no less, could clearly wield a pen every bit as he could destroy Japanese armies in battle (a feat he achieved twice, first in 1944 and again in 1945). When the book was first published it was an instant publishing sensation with the first edition of 20,000 selling out immediately. The Field recorded: “Of all the world’s greatest records of war and military adventure, this story must surely take its place among the greatest. It is told with a wealth of human understanding, a gift of vivid description, and a revelation of the indomitable spirit of the fighting man that can seldom have been equalled – let alone surpassed – in military history.” The London Evening Standard was as effusive in its praise: “He has written the best general’s book of World War II. Nobody who reads his account of the war, meticulously honest yet deeply moving, will doubt that here is a soldier of stature and a man among men.” The author John Masters, who served in the 14th Army, wrote in the New York Times on 19 November 1961 that it was “a dramatic story with one principal character and several hundred subordinate characters”, arguing that Slim was “an expert soldier and an expert writer”. The book remains a best seller today.

The following year Slim also published an anthology of speeches and lectures, loosely based on the theme of leadership, called Courage and Other Broadcasts. Then in 1959 he published his second book, Unofficial History, which bears out in full Masters’ description of Slim as a superb writer. It was a deeply personal, honest though light hearted account of events during his service. It received widespread acclaim. The author John Connell described it as “for the most part uproarious fun. If Bill Slim hadn’t been a first-rate soldier, what a short story writer he might have made.” For its part, The National Review wrote: “One of the most significant aspects of Field Marshal Slim’s book is the affectionate respect he shows when he writes about British and Indian soldiers. He finds plenty to amuse him too. I doubt whether a kindlier or truer description of the contemporary soldier has been given anywhere than in Unofficial History … It is one of the most delightful and amusing books about modern campaigning I have ever read.”

1. The General Wondered Why https://amzn.eu/d/45gHfOH

June 1, 2023

Recent discoveries in ancient DNA

The Psmiths, John and Jane, decided to jointly review a book by David Reich called Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. This is Jane’s first contribution to an extended email thread between the Psmiths:

The problem with history is that there just isn’t enough of it. We’ve been around for, what, fifty thousand years? Conservatively.1 And we’ve barely written things down for a tenth of that. Archaeological excavation can take you a little farther back, but as the archaeologists always like to remind us, pots are not people. If you get lucky with a society that made things out of durable materials in a cold and/or dry environment (or you get very lucky with anaerobic preservation of organic materials, like in ice or bogs), maybe you can trace a material culture’s expansion and contraction across time and space. But that won’t tell you whether it’s a function of people moving and taking their stuff with them, or people’s neighbors going “ooh, using string to make patterns on your pots, that’s cool” and copying it. It certainly doesn’t tell you what their descendants were doing several thousand years later, potentially in an entirely different place and probably using an entirely different suite of technologies. Trying to understand what happened in the human past based on the historical and archaeological records is like walking into a room where a bomb has gone off and trying to reconstruct the locations of all the objects before the explosion. You can get some idea, but it’s all very broad strokes. And actually it’s worse than that, because it wasn’t just one explosion, it was lots, and we wouldn’t even know how many if we didn’t have a way of winding the clock back. But these days we do, and it’s ancient DNA.

Sometime between when my grandfather gave me a copy of Luca Cavalli-Sforza’s Genes, Peoples, and Languages for my birthday and when you and I decided to read Reich’s book together, two big things happened: humans got really, really good at sequencing and reading genomes, and Svante Pääbo’s lab in Leipzig got really, really good at extracting DNA from ancient bones. (How they developed their procedures is actually a really interesting story, which Pääbo retells in his book, but Reich — whose lab uses the same techniques on an industrial scale — gives a good, brief summary of how it works.) Together, these two advances unlocked … well, not quite everything about the deep past, but an absolutely enormous amount. Suddenly we can track the people, not just the pots, and the story is more complicated and fascinating than anything we might have expected. I’ve written elsewhere about some of the aDNA discoveries about human evolution (Neanderthal admixture, the Denisovans, etc.), but I’m even more excited about what ancient DNA reveals about our more recent past. Luckily, that’s what Reich spends most of the book on, with discussion of ancient ghost populations who now exist only in admixture and then chapters on the specific population genetic histories of Europe, India, North America, East Asia, and Africa, each of which contains some discoveries that would make (at least the more sensible) archaeologists and historical linguists go “well, duh” and others that are real surprises.

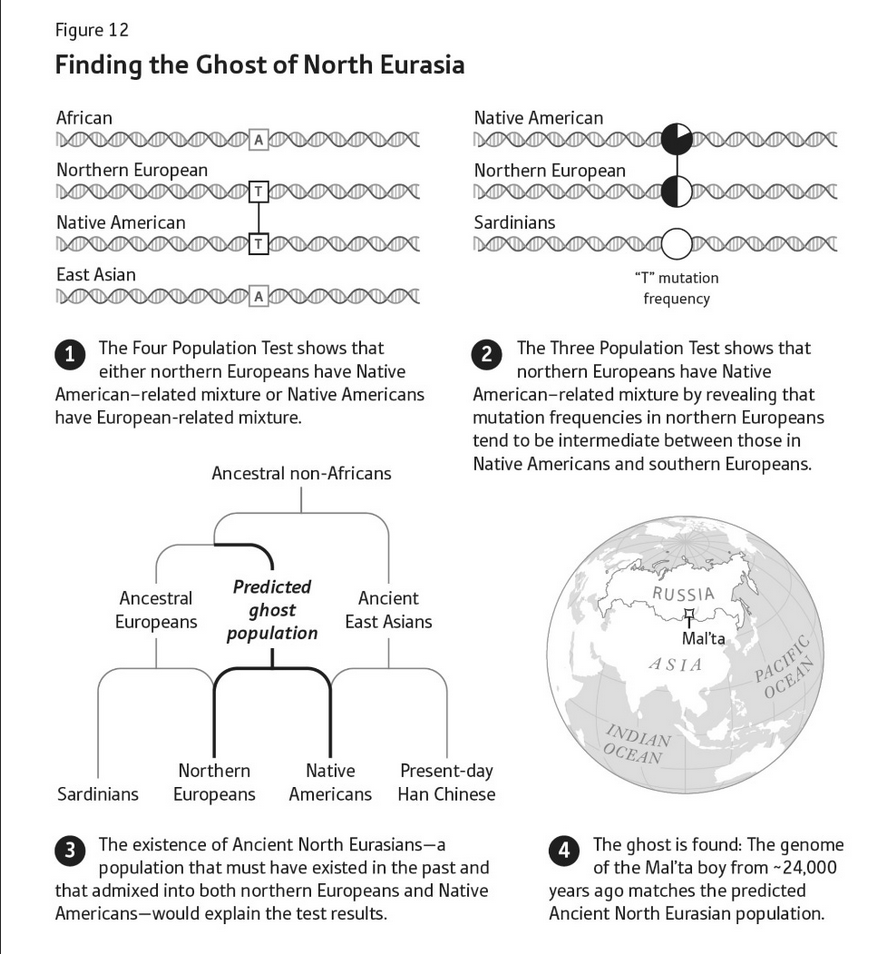

One of the “duh” stories is the final, conclusive identification of the people who brought horses, wagons, and Indo-European languages to Europe with the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic Steppe and their descendants. (David Anthony gives a very good overview of the archaeological case for this in The Wheel, the Horse, and Language, including some very cool experimental archaeology about horse teeth; you have my permission to skim the sections on pots.) My favorite surprising result, though, comes from a little farther north. People usually assume that Native Americans and East Asians share a common ancestor who split from the ancestors of Europeans and Africans before dividing into those two populations, but when Reich’s lab was trying to test the idea they found, to their surprise, that in places where Northern European genomes differ from Africans’, they are closer to Native Americans than to East Asians. Then, using a different set of statistical techniques, they found that Northern European populations were the product of mixture between two groups, one very similar to Sardinians (who are themselves almost-unmixed descendants of the first European farmers) and one that is most similar to Native Americans. They theorized a “ghost” population, which they called the “Ancient North Eurasians”, who had contributed DNA both to the population that would eventually cross the Bering land bridge and to the non-Early European Farmer ancestors of modern Northern Europeans. Several years later, another team sequenced the genome of a boy who died in Siberia 24kya and who was a perfect match for that theorized ghost ANE population.

But we’ve already established that I’m the prehistory nerd in this family; were you as jazzed as I was to read about the discovery of the Ancient North Eurasians?

1. That’s the latest plausible date for the arrival of full “behavioral modernity” in Africa, though our genus goes back about two million years, tool use probably three million, and I think there’s a good case that Homo was meaningfully “us” by 500kya. (That’s “thousand years ago” in “I talk about deep history so much I need an acronym”, fyi.)

May 28, 2023

Breakout from Anzio! – WW2 – Week 248 – May 27, 1944

World War Two

Published 27 May 2023After four months, the Allies breakout from their bridgehead at Anzio and meet with the advancing troops heading north after the fall of Monte Cassino last week. The Japanese begin phase two of their big operation in China, and both the Soviets and the Western Allies continue making plans for their massive June offensives to squeeze the Axis from both sides of Europe.

(more…)

May 27, 2023

“David Johnston is an honourable man”

From this heading, you might be a bit reminded of Mark Antony’s funeral oration for Caesar, as imagined by William Shakespeare (well, I was, so you’ll have to suffer a few lines of iambic pentameter):

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones;

So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus

Hath told you Caesar was ambitious:

If it were so, it was a grievous fault,

And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it.Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest–

For Brutus is an honourable man;

So are they all, all honourable men–

Come I to speak in Caesar’s funeral.

He was my friend, faithful and just to me:

But Brutus says he was ambitious;

And Brutus is an honourable man.He hath brought many captives home to Rome

Whose ransoms did the general coffers fill:

Did this in Caesar seem ambitious?

When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept:

Ambition should be made of sterner stuff:

Yet Brutus says he was ambitious;

And Brutus is an honourable man.

Perhaps I’m reading too much into the opening line of Philippe Lagassé’s article about former Governor General David Johnston’s role in whitewashing the Trudeau running dogs, however:

David Johnston is an honourable man. As a former governor general, he holds the title of Right Honourable and he wears it better than many former prime ministers who share that moniker. Johnston is also a champion of trust in democratic institutions; he literally wrote a book called Trust: Twenty Ways to Build a Better Country.

Although his appointment has been plagued by questions about his perceived conflicts of interest, it’s hard to accept that Johnston set out to protect the Liberal party. Whether one agrees with him or not, Johnston’s conclusions were arrived at sincerely and in keeping with his view that “Democracy is built on trust.” Unfortunately, his recommendation against a public inquiry is not only bewildering from a political perspective, but could erode the very trust in democracy that he wants to strengthen.

Whatever we think about Johnston’s first report, we should be concerned with his appointment as the special rapporteur. Aside from the perceived conflicts of interest, we should ask why a former governor general accepted the role in the first place. Serving as a vice-regal representative should be the last public role an individual performs. Any other public duty performed by a former governor general or lieutenant governor, however well-intentioned and performed, carries risks that can diminish these offices. Johnston’s experience is a cautionary tale for future vice-regals.

The governor general is the second-highest office of the Canadian state, under the monarch alone. The King’s representative performs most of the Crown’s head of state functions in Canada, both constitutional and ceremonial. Official independence and non-partisanship are essential parts of the head of state function. Canadians should be able to trust (there’s that word again) that governors general will be impartial in the exercise of their constitutional powers. We need only look at the 2008 prorogation controversy and the 2017 election in British Columbia to see why this matters for Canadian democracy.

Although less vital, independence and non-partisanship are also important for the governor general’s ceremonial roles. Having the governor general bestow honours ensures that Canadians are recognized by a neutral, but high-standing, representative of the state. An ardent Conservative can receive the Order of Canada while a Liberal government is in power without wincing, since the prime minister and cabinet are kept at a safe distance from the whole thing.

[…]

Former vice-regal representatives should take heed. They would do well to avoid becoming a new set of “retired Supreme Court justices”, whose judicial halo effect has become comically overused to stem political controversy. Indeed, Canadians should insist that the governor general’s salary and annuity come with a tacit bargain: you were set for life to ensure your impartiality and independence, now we never want to hear you wading into political controversies or see you hold another public office again.

This should not be too much to ask of the King’s representatives. No other public role has the formal role stature of a vice-regal office, aside from the monarch, and none are as carefully insulated from partisan battles. The office of governor general should be held by those at the end of a remarkable career, as a final act of independent and impartial public service.

Also in The Line, Mitch Heimpel seems to be a bit less willing to tolerate the use of a former Governor General as ablative shielding for a compromised government:

In the end, David Johnston proved himself to be exactly what his critics argued he always was.

A fervent defender of his advantaged status quo. Another among the thoroughly compromised set of politicians, senior civil servants and academics who have, over the decades when it comes to Canadian foreign policy regarding China, taken the money and run. The idea that he was ever going to be anything else was a figment of our own collective fantasy.

We believed we were a serious country. David Johnston has laughed in our faces at the very thought.

The families of members of Parliament have been targeted for possible “sanctions”? No matter.

Our elections are the subject of coordinated foreign intelligence operations? Well, sure. But what is democracy really?

Really, you see, Johnston told us — without ever being quite so direct about it, because people of Johnston’s polite air are rarely so crass — the media was your problem. They published things without the appropriate “context.”

Choosing Johnston was always a bit grubby. It was meant to politically neuter Conservatives because, after all, Stephen Harper appointed him to be the governor general. How could he possibly be compromised? Yes, he’s known the prime minister whose government he was investigating since Justin Trudeau was a small child. And, yes, as a university president, he was long an advocate for more open relations with China. And, yes, he involved with the Trudeau Foundation, which has found itself at the heart of the question of foreign interference coordinated by the Chinese Communist Party, but …

No, there is no “but”.

There is no other democracy which would have successfully conducted an elaborate farce of this magnitude to tell its citizens what it is painfully obvious that it wanted to tell them all along: You have no right to know.

QotD: The war elephant’s primary weapon was psychological, not physical

The Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC), which I’ve discussed here is instructive. Porus’ army deployed elephants against Alexander’s infantry – what is useful to note here is that Alexander’s high quality infantry has minimal experience fighting elephants and no special tactics for them. Alexander’s troops remained in close formation (in the Macedonian sarissa phalanx, with supporting light troops) and advanced into the elephant charge (Arr. Anab. 5.17.3) – this is, as we’ll see next time, hardly the right way to fight elephants. And yet – the Macedonian phalanx holds together and triumphs, eventually driving the elephants back into Porus’ infantry (Arr. Anab. 5.17.6-7).

So it is possible – even without special anti-elephant weapons or tactics – for very high quality infantry (and we should be clear about this: Alexander’s phalanx was as battle hardened as troops come) to resist the charge of elephants. Nevertheless, the terror element of the onrush of elephants must be stressed: if being charged by a horse is scary, being charged by a 9ft tall, 4-ton war beast must be truly terrifying.

Yet – in the Mediterranean at least – stories of elephants smashing infantry lines through the pure terror of their onset are actually rare. This point is often obscured by modern treatments of some of the key Romans vs. Elephants battles (Heraclea, Bagradas, etc), which often describe elephants crashing through Roman lines when, in fact, the ancient sources offer a somewhat more careful picture. It also tends to get lost on video-games where the key use of elephants is to rout enemy units through some “terror” ability (as in Rome II: Total War) or to actually massacre the entire force (as in Age of Empires).

At Bagradas (255 B.C. – a rare Carthaginian victory on land in the First Punic War), for instance, Polybius (Plb. 1.34) is clear that the onset of the elephants does not break the Roman lines – if for no other reason than the Romans were ordered quite deep (read: the usual triple Roman infantry line). Instead, the elephants disorder the Roman line. In the spaces between the elephants, the Romans slipped through, but encountered a Carthaginian phalanx still in good order advancing a safe distance behind the elephants and were cut down by the infantry, while those caught in front of the elephants were encircled and routed by the Carthaginian cavalry. What the elephants accomplished was throwing out the Roman fighting formation, leaving the Roman infantry confused and vulnerable to the other arms of the Carthaginian army.

So the value of elephants is less in the shock of their charge as in the disorder that they promote among infantry. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, heavy infantry rely on dense formations to be effective. Elephants, as a weapon-system, break up that formation, forcing infantry to scatter out of the way or separating supporting units, thus rendering the infantry vulnerable. The charge of elephants doesn’t wipe out the infantry, but it renders them vulnerable to other forces – supporting infantry, cavalry – which do.

Elephants could also be used as area denial weapons. One reading of the (admittedly somewhat poor) evidence suggests that this is how Pyrrhus of Epirus used his elephants – to great effect – against the Romans. It is sometimes argued that Pyrrhus essentially created an “articulated phalanx” using lighter infantry and elephants to cover gaps – effectively joints – in his main heavy pike phalanx line. This allowed his phalanx – normally a relatively inflexible formation – to pivot.

This area denial effect was far stronger with cavalry because of how elephants interact with horses. Horses in general – especially horses unfamiliar with elephants – are terrified of the creatures and will generally refuse to go near them. Thus at Ipsus (301 B.C.; Plut. Demetrius 29.3), Demetrius’ Macedonian cavalry is cut off from the battle by Seleucus’ elephants, essentially walled off by the refusal of the horses to advance. This effect can resolved for horses familiarized with elephants prior to battle (something Caesar did prior to the Battle of Thapsus, 46 B.C.), but the concern seems never to totally go away. I don’t think I fully endorse Peter Connolly’s judgment in Greece and Rome At War (1981) that Hellenistic armies (read: post-Alexander armies) used elephants “almost exclusively” for this purpose (elephants often seem positioned against infantry in Hellenistic battle orders), but spoiling enemy cavalry attacks this way was a core use of elephants, if not the primary one.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part I: Battle Pachyderms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-26.

May 23, 2023

Mustard: A Spicy History

The History Guy: History Deserves to be Remembered

Published 15 Feb 2023In 2018 The Atlantic observed “For some Americans, a trip to the ballpark isn’t complete without the bright-yellow squiggle of French’s mustard atop a hot dog … Yet few realize that this condiment has been equally essential — maybe more so — for the past 6,000 years.”

(more…)