In The Line, retired Canadian Lieutenant General Mike Day distills down all the airy phrases to see just what the Canadian government is actually going to do in the Indo-Pacific as opposed to merely talking about it:

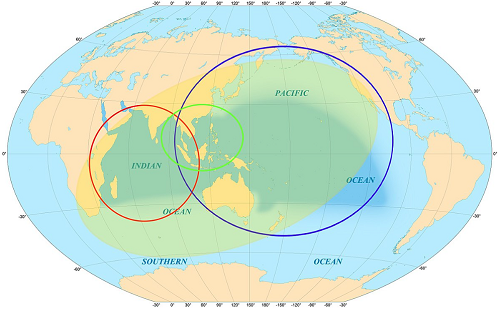

“Red circle/oval roughly depicts the Indian Ocean region. Blue circle/oval covers the Pacific region. Green oval covers ASEAN. Yellow overlay covers the Indo Pacific.”

Map annotation by Eric Gaba via Wikimedia Commons.

A formal public-policy statement from the Government of Canada is a rare thing. It is even rarer when it is not just a speech but a published written document. The rarest of these is undoubtedly when such a document focuses on foreign policy. When Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly recently pitched her “once-in-a-generation shift” toward the Indo-Pacific, much was made of why Canada was doing it and what it would achieve. No fewer than four cabinet ministers took part in the announcement. Canada will, they announced, step up naval patrols of the region, continue to expand trade with China while also tightening our protections of intellectual property and ownership rules for strategic industries, and use “Team Canada” trade missions to boost commercial links with other growing regional economic powers, including India. We seek also to expand our intelligence and cybersecurity links with allies and partners in the region.

Now that the dust on the rhetoric has settled, closer examination reveals that this might simply be an exercise of branding separate activities into a marketing-friendly bundle, as opposed to a coherent plan focused on achieving specific outcomes.

In examining the document two approaches are equally useful in assessing value: whether the content has some substance and whether the policy framework is sufficiently robust to hang various activities and plans on its body.

Three hints are provided as to why the new plan might not be the cornerstone of Canada’s foreign policy that it portends to be. Firstly, operating in the “National Interest”, a phrase used six separate times over the 26 pages, is given neither form nor function and lacks any definition. It is reminiscent of the Cheshire Cat talking to Alice asking her “where do you want to get to”. When Alice replies that “I don’t much care …” the Cheshire Cat wisely suggests that “Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.” With no definition of national interests pretty much anything can be hand waved as to being necessary and required, or not, for its achievement.

This leads in turn to the second hint that the plan might be more posturing than substance. Lacking the single aimpoint of operating in the national interest, the “objectives” supposedly fill that gap by providing a set of specific achievements which in combination would be a sufficiently clear aimpoint. But normally objectives can, and should, be thought of as something specific and measurable, allowing plans to be developed to achieve them. “Save 100 dollars this month” or perhaps, in more relevant terms, “Increase our trade in the Indo-Pacific region by 100 per cent over the five years of this policy enactment.” Plans can then be developed to achieve those objectives. But reviewing those objectives reveals that they are themselves actions, not end-states. It appears that the policy is based on “doing, not achieving”. I am reminded of my sons many years ago. When asked if their rooms were clean, they would reply, “I’m cleaning it.” The process was enduring but we most certainly disagreed on the value of the activity as opposed to achieving a measurable result. Under this construct the government can claim that as long as Canada is doing stuff the policy should be considered a success.