The Film Archives

Published on 27 Jan 2014George Packer (born August 13, 1960) is an American journalist, novelist, and playwright.

He is perhaps best known for his writings for The New Yorker about U.S. foreign policy and for his related book The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq.

Packer was born in Santa Clara, California. Packer’s parents, Nancy (née Huddleston) and Herbert Packer, were both academics at Stanford University; his maternal grandfather was George Huddleston, a congressman from Alabama. His sister, Ann Packer, is also a writer. His father was Jewish and his mother was from a Christian background. Packer graduated from Yale College, where he lived in Calhoun College, in 1982, and served in the Peace Corps in Togo. His essays and articles have appeared in Boston Review, The Nation, World Affairs, Harper’s, The New York Times, and The New Yorker, among other publications. Packer was a columnist for Mother Jones and has been a staff writer for The New Yorker since May 2003.

Packer was a Holtzbrinck Fellow Class of Fall 2009 at the American Academy in Berlin.

His book The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq analyzes the events that led to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and reports on subsequent developments in that country, largely based on interviews with ordinary Iraqis. He was a supporter of the Iraq war. He was a finalist for the 2004 Michael Kelly Award.

He is married to Laura Secor and was previously married to Michele Millon.

Books

The Village of Waiting (1988). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1st Farrar edition, 2001). Pb. ISBN 0-374-52780-6

The Half Man (1991). Random House ISBN 0-394-58192-X

Central Square (1998). Graywolf Press ISBN 1-55597-277-2

Blood of the Liberals (2000). Farrar, Straus and Giroux ISBN 0-374-25142-8

The Fight is for Democracy: Winning the War of Ideas in America and the World (2003, as editor). Harper Perennial. Pb. ISBN 0-06-053249-1

The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq (2005) Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2005 ISBN 0-374-29963-3

Betrayed: A Play (2008) Faber & Faber

Interesting Times: Writings from a Turbulent Decade (2009). ISBN 978-0-374-17572-6

The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America (2013). ISBN 978-0-374-10241-8Articles

Packer, George (28 September 2009). “A Reporter at Large: The Last Mission”. The New Yorker 85 (30): 38-55. [Richard Holbrooke’s plan to avoid the mistakes of Vietnam in Afghanistan].

Packer, George (15 March 2010). “A Reporter at Large: Obama’s Lost Year”. The New Yorker 86 (4): 40-51.

Packer, George (12 September 2011). “A Reporter at Large: Coming Apart”. The New Yorker. [An assessment of the post 9/11 decade]

Packer, George (27 May 2013). “A Reporter at Large: Change the World”. The New Yorker.

July 31, 2019

July 24, 2019

thoughts about writing

exurb1a

Published on 23 Jul 2019Apologies for the resolution in some places. Apologies for the words in all places.

Books I enjoyed while I was in creative pinches ►

Zen in the Art of Writing – Ray Bradbury

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1…What I Talk About When I Talk About Running – Haruki Murakami

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2…The Elements of Style – William Strunk Jr.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3…On Writing – Sol Stein

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1…The Book of Five Rings – Miyamoto Musashi

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/8…Why I Write – George Orwell

http://orwell.ru/library/essays/wiw/english/e_wiwMy stuff –

The Fifth Science Paperback ► https://tinyurl.com/y5zj33s5 (you may need to change your region accordingly: .co.uk, etc)

I also make horrendous music ► https://soundcloud.com/exurbia-1

Help me to do this full-time, if you’re deranged enough ► https://www.patreon.com/exurb1r?ty=h

The rest of my books ► https://tinyurl.com/ycnl5bo3

June 13, 2019

Americans “don’t really believe in foreigners”

A few days back, Sarah Hoyt wrote a long post about the actual differences between American culture and the many different cultures that most Americans have difficulty understanding:

I don’t think anyone who hasn’t actually acculturated between two countries understands how different cultures can be, deep down, at the bone level and the most basic reactions level, let alone what causes the difference, from inherited influences to just deep built in assumptions about climate/physical plant/fauna.

And some of the people who have acculturated, at that, might not be self-aware enough to see the difference, and just replace one set of assumptions with another and roll with it. (Or get caught somewhere between. Well, to some extent we all get caught somewhere between. The question is, what percentage is in the new country. I’d say for me, after being in Portugal recently, probably 95% American. There are things trained in before the age of 3 which I’ll never let go of, though some got truly weird with the acculturation, like how I react to “shame.”)

That experience this weekend was the “clicking in” of something that’s been bothering me for a long time. In our writers’ group I used to run across people who projected modern AMERICAN female back into the time of pharaohs. One of my best friends refused to believe me when I told her there was zero chance of an alien race having the same university system as the US since even Portugal (avowedly human) doesn’t. There were other things. You guys have heard me rant about several “historical” books that make the past exactly like the future only with different tech. The fact that they don’t understand that tech affects not just how people live but how they think, feel and react is another of those things I don’t get, as I think even within living memory we should be able to see how different things have gotten. See for instance not wearing of aprons, because the clothes are cheap enough and abundant enough that ruining a shirt is not a big deal, unless it’s a very good shirt.

Technological shifts in living memory have made ordinary life from before the new technology (like cheap, dependable cell phones) almost unimaginable. How many movies and TV shows from before the mobile phone became widely available depended as a plot point on the characters being unable to communicate with one another at key moments? Many mystery novels of the pre-mobile-phone era probably make no sense at all to modern readers because instant communication has become “baked in” to our world.

The clothing aspect has been less obviously important, yet only a couple of generations back, most people owned perhaps three changes of clothing, including one “good” suit/dress for church-going or special occasions. We’ve become so wealthy as a culture that almost everyone has more than enough clothes for any imagined need … although church-going has become almost exotic to urban and even suburban folks, and formal attire is becoming more and more rare. (But everyone has more T-shirts and shorts than they know what to do with.)

But until this weekend I didn’t realize how prevalent and universal it is, since the clash took place between two people from native anglophone cultures, both of which are denizens of the net and contact people of other countries, regularly. Okay, one of them didn’t know she was dealing with a foreigner […] This weekend I realized people don’t really believe in foreign countries either. They’re willing to accept that some things (and those usually conform to their mental picture of the generic “culture” or “region”) are different, but that the fundamentals and the cherished unexamined assumptions might be different is unthinkable — literally. And if we can think of them, we still assume the other country is somehow “wrong” or worse “pretending” to be different to be contrary.

This means, ultimately, that even an era of instant all over the world communication, human tribalism still wins. And with it, I suppose, nationalism.

The wave of populism in the west that has taken the establishment and the mainstream media by surprise is a predictable response to the globalist attitudes of the elites. If you work hard enough at it, you can provoke unpleasant responses from those who don’t agree with your worldview, and the transnational elites have been working very hard indeed.

There are other implications: since it’s virtually impossible to avoid faster communication and more widespread travel in the future, this is going to make the next couple/three centuries a series of epic clashes, until either some sort of understanding emerges or polarized cultures can immigrate to the stars and far far away from each other.

Mass immigration is a REALLY bad idea (‘mkay) not that this is a surprise to any of you. People inhabiting enclaves of “their kind” are slow to acculturate (three generations, if it happens at all.) And the number of people coming over the Southern border is like nothing we’ve ever experienced before. And trust me, in terms of functionality, you do NOT want to import any culture descended from 17th century Spain. There is a reason that the American countries South of us are in crisis on a more or less permanent basis, and that Brazil, screwed up though it is, is more functional than the others. No, just no.

I’m certainly not against immigration, but I strongly believe it is possible to have too much immigration, as Europe and the United States are being forced to confront. When people leave their native land to go somewhere else, be it for economic or political reasons, there’s a natural expectation that they will at least attempt to acculturate to their new country. To western elites, this is wrong (or at least, misguided) and “we” should encourage new immigrants to avoid acculturation and to embrace and celebrate the culture they came from. Because reasons. And a lot of immigrants are happy to avoid the hard work of learning how to fit in to the foreign culture they find themselves in — and it is hard work — leading to second or third generations who still can’t or won’t fit in and adapt to the culture.

Let me just say that is one more proof of “people don’t really believe in foreigners.”

Sure, a lot of American culture is triumphant and imitated. Only it’s more “spoofed” because what they imitate is what they see in movies, and proving that humans prefer narrative to lack there of, even when it makes no sense, the bad parts are often picked up first. And they’re often bad parts only seen in movies, btw. Like certain underclass behaviors being seen as glamorous.

But it’s an overlay. At a deep down level, these people dressing in jeans and t-shirts are still foreign and — THIS IS VERY IMPORTANT — don’t believe Americans software-in-the-head is different, which leads to cargo-cultish attempts to import American successes without getting what brings them about, from innovation, to social mobility to freedom of speech. Not really, not at a deep level.

[…]

This means the left’s project of “fighting nationalism” is not just doomed, but it’s stupid as eating rocks, and will cause only unending misery suffering and war. (So, SOP for Marxists. In fact, chalk this whole internationalism bullshit as something else Marx was wrong about. Workers of the world unite, my little sore feet.)

June 11, 2019

QotD: Advice to young men

Since Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, published his celebrated letters to his morganatic son, in 1744, there has been no adequate book, in English, of advice to young men. I say adequate, and the adjective tells the whole story. There is not, of course, a college president or a boss Y.M.C.A. secretary, or an uplifting preacher in the United States who has not written such a book, but all of them are alike filled with bilge. They depict and advocate a life that no normal young man wants to live, or could live without ruin if he wanted to. They are full of Sunday-school platitudes and Boy Scout snuffling. If they were swallowed by the youth of today the Republic of tomorrow would be a nation of idiots.H.L. Mencken, “Another Long-Awaited Book”, Chicago Tribune, 1926-09-12.

June 10, 2019

QotD: Robert Heinlein on “honest work”

The beginning of 1939 found me flat broke following a disastrous political campaign (I ran a strong second best, but in politics there are no prizes for place or show).

I was highly skilled in ordnance, gunnery, and fire control for Naval vessels, a skill for which there was no demand ashore — and I had a piece of paper from the Secretary of the Navy telling me that I was a waste of space — “totally and permanently disabled” was the phraseology. I “owned” a heavily-mortgaged house.

About then Thrilling Wonder Stories ran a house ad reading (more or less):

GIANT PRIZE CONTEST —

Amateur Writers!!!!!!

First Prize $50 Fifty Dollars $50In 1939 one could fill three station wagons with fifty dollars worth of groceries.

Today I can pick up fifty dollars in groceries unassisted — perhaps I’ve grown stronger.

So I wrote the story “Life-Line.” It took me four days — I am a slow typist. I did not send it to Thrilling Wonder; I sent it to Astounding, figuring they would not be so swamped with amateur short stories.

Astounding bought it… for $70, or $20 more than that “Grand Prize” — and there was never a chance that I would ever again look for honest work.

(“Honest work” — an euphemism for underpaid bodily exertion, done standing up or on your knees, often in bad weather or other nasty circumstances, and frequently involving shovels, picks, hoes, assembly lines, tractors, and unsympathetic supervisors. It has never appealed to me. Sitting at a typewriter in a nice warm room, with no boss, cannot possibly be described as “honest work.”)

Robert A. Heinlein, 1980.

June 9, 2019

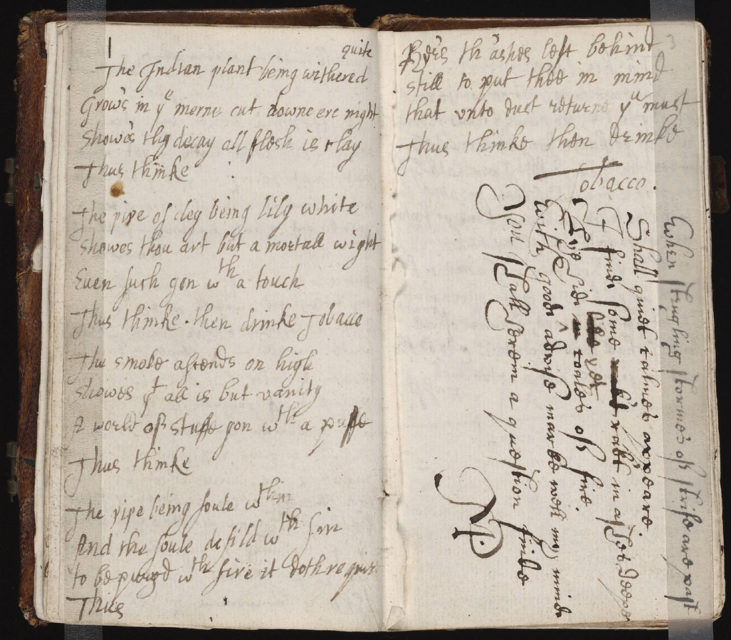

The blog as a modern “commonplace book”

I’ve been blogging continuously for over fifteen years, but I’ve never found — or even considered — a single unifying theme for the blog. There are consistencies over the years, like the QotD posts, but in general the blog acts as a place for me to note things that interest, excite, or agitate me. After my grandfather died in 1979, I inherited a few of his notebooks, which included scores of lists on all kinds of things … my grandmother said it was all gathered to help with crossword puzzles, but the range of information was much wider than you’d normally find in crosswords. I think, had he lived long enough, my grandfather would have been a dedicated blogger. The blogging world has a lot of blogs like mine, where the blogger notes seemingly random bits of information, and this is far from new: they used to be called “commonplace books“:

Anonymous mid-17th century manuscript containing poems by various authors, in various hands, including Shakespeare’s second sonnet.

Wikimedia Commons.

Commonplace books (or commonplaces) are a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They have been kept from antiquity, and were kept particularly during the Renaissance and in the nineteenth century. Such books are essentially scrapbooks filled with items of every kind: recipes, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, proverbs, prayers, legal formulas. Commonplaces are used by readers, writers, students, and scholars as an aid for remembering useful concepts or facts. Each one is unique to its creator’s particular interests but they almost always include passages found in other texts, sometimes accompanied by the compiler’s responses. They became significant in Early Modern Europe.

“Commonplace” is a translation of the Latin term locus communis (from Greek tópos koinós, see literary topos) which means “a general or common topic”, such as a statement of proverbial wisdom. In this original sense, commonplace books were collections of such sayings, such as John Milton’s example. Scholars now understand them to include manuscripts in which an individual collects material which have a common theme, such as ethics, or exploring several themes in one volume. Commonplace books are private collections of information, but they are not diaries or travelogues.

In 1685 the English Enlightenment philosopher John Locke wrote a treatise in French on commonplace books, translated into English in 1706 as A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books, “in which techniques for entering proverbs, quotations, ideas, speeches were formulated. Locke gave specific advice on how to arrange material by subject and category, using such key topics as love, politics, or religion. Commonplace books, it must be stressed, are not journals, which are chronological and introspective.”

By the early eighteenth century they had become an information management device in which a note-taker stored quotations, observations and definitions. They were used in private households to collate ethical or informative texts, sometimes alongside recipes or medical formulae. For women, who were excluded from formal higher education, the commonplace book could be a repository of intellectual references. The gentlewoman Elizabeth Lyttelton kept one from the 1670s to 1713 and a typical example was published by Mrs Anna Jameson in 1855, including headings such as Ethical Fragments; Theological; Literature and Art. Commonplace books were used by scientists and other thinkers in the same way that a database might now be used: Carl Linnaeus, for instance, used commonplacing techniques to invent and arrange the nomenclature of his Systema Naturae (which is the basis for the system used by scientists today). The commonplace book was often a lifelong habit: for example the English-Australian artist Georgina McCrae kept a commonplace book from 1828-1865.

May 26, 2019

QotD: Maurice Sendak on childhood

We’ll begin our tribute to Maurice Sendak with an excerpt of our 1986 interview, in which he told me that when he was a child, adults looked big and grotesque to him, and he couldn’t imagine ever becoming one.

MAURICE SENDAK: It was inconceivable to me as a child that I would be an adult. I mean, one assumed that it would happen, but obviously it didn’t happen, or if it did, it happened when your back was turned, and then suddenly you were there. So I couldn’t have thought about it much.

TERRY GROSS: Because adults seemed really big and different, you couldn’t imagine becoming one?

SENDAK: And awful. Yeah. I mean they were mostly dreadful, and if the option were to become an adult was to become another dreadful creature, then best not, although I think there had to be a kind of normal anticipation of that moment happening because being a child was even worse.

I mean, being a child was being a child — was being a creature without power, without pocket money, without escape routes of any kind. So I didn’t want to be a child.

I remember how much — when I was a small boy I was taken to see a version of Peter Pan. I detested it. I mean the sentimental idea that anybody would want to remain a boy, I don’t — I couldn’t have thought it out then, but I did later, certainly, that this was a conceit that could only occur in the mind of a very sentimental writer, that any child would want to remain in childhood. It’s not possible. The wish is to get out.

“‘Fresh Air’ Remembers Author Maurice Sendak”, NPR Books, 2012-05-08.

May 10, 2019

Microsoft can’t get worse than old Clippy? “Hold my non-alcoholic beer”

Libby Emmons reports on a new Microsoft Word plugin that puts Clippy into the history books:

Coming soon to a word processing app you probably already subscribe to is Microsoft’s new Ideas plugin. This leap forward in the predictive text trend will endeavor to help you be less offensive. Worried you might be a little bit racist? A little gender confused? Not sure about the difference between disabled persons and persons who are disabled? Never fear, Microsoft will fix your language for you.

Using machine learning and AI, Microsoft’s Ideas in Word will help writers be their least offensive, most milquetoast selves. Just like spell check and grammar check function, Ideas will make suggestions as to how to improve your text to be more inclusive. On the surface, this seems like a terrible idea, but when we dig further beneath the impulse, and the functionality of the program, it gets even worse. What’s happening is that AI and machine learning are going to be the background of pretty much every application, learning from our behaviours not only how we’d like to format our PowerPoint presentations, but learning, across platforms, how best to construct language so that we say what we are wanted to say as opposed to what we really mean.

There is an essential component of honest communication, namely that a person express themselves using their own words. When children are learning to talk and to articulate themselves, they are told to “use your words.” Microsoft will give writers the option of using someone else’s words, some amalgamation of users’ words across the platform, and the result will be that the ideas exhibited will not be the writer’s own.

April 8, 2019

April 7, 2019

QotD: Good writers and bad

Thinking about it, what often makes a writer good, is that they avoid the things that all bad writers seem to share. In this sense, “good” is not a state in itself, but simply not being in the state we call “bad.” A great wordsmith is further away from the state of bad writing than someone who is just an average writer. That average writer can appear to be much better, by offering keen insights and clever observations. The path to becoming a good writer, therefore, starts with avoiding the things that define a bad writer.

The most common trait of bad writers, it seems, is they write about themselves. Unless you are an international man of mystery, you’re not that interesting. No one is. Bad writers, always seem to think they are the most interesting people they know. This is what made former President Obama such a boring speaker. No matter the subject, his speech was going to be a meditation on his thoughts and feelings about the subject. It became a game of sorts to count how many times he referenced himself in a speech.

That’s the hallmark of bad writing. Instead of focusing on the subject, the writer focuses on himself, which suggests he does not know the material. Even when relating an experience or conversation, the good writer makes himself a secondary character in the story, not the focus. Bad writers are always the hero of everything they write, as if they are trying to convince the reader of something about themselves. Good writers avoid this and focus on the subject of their writing.

The Z Man, “How To Be A Bad Writer”, The Z Blog, 2019-03-03.

April 5, 2019

April 4, 2019

George Orwell BBC Arena Part 1 – Such, Such Were the Joys

Alan Ruben

Published on 4 Mar 2013Part 1 of an in-depth 5 part series about George Orwell made in 1983.

March 19, 2019

QotD: Celebrity intellectuals

Tyler Cowen posted his latest Conversations with Tyler. His guest was Malcolm Gladwell, the famous gadfly and popularizer of the blank slate. Of course, Cowen slobbers all over him, because that’s what good thinkers are supposed to do when they get to meet someone like Gladwell. It’s a way of letting the other good thinkers know you are not the sort that colors outside the lines. Gladwell is one of those guys who is more famous for what he represents than anything he has said or written.

Celebrity intellectuals are not famous because they have offered up a great insight or discovery. There’s no money in that. New ideas challenge the orthodoxy. The people with the money to help an aspiring celebrity intellectual live the sort of life they deserve tend not to like challenges to the orthodoxy. Instead they gravitate to people who confirm that the current arrangements are as the heavens ordained. That’s Gladwell. His celebrity is rooted in his ability to flatter the Cloud People.

The typical path to celebrity for these guys is not much different than the way mediocre comics get rich and famous. The game is to flatter the right audience. Making a bunch of bad whites in the hill country feel good about themselves is not a path to the easy life. You can make a nice living, but you’re not going to be doing Ted Talks or getting five figures to do the college circuit. Figure how to let the Cloud People on the Upper West Side feel like champions and you have the golden ticket.

The Z Man, “The Fading Star”, The Z Blog, 2017-03-16.

March 12, 2019

QotD: The creed of the editor

It is part of the woolly lore of editors and lawyers alike: the misplaced or absent comma in a statute or a contract that ends up costing somebody zillions of dollars. There really are not many examples of this happening, but lawyers have a responsibility to behave as though the danger were omnipresent. The thought of a comma disaster encourages close attention to detail: it provides a spur to the spirit during long hours of copy-editing.

As for print editors, believing in the myth of the expensive punctuation mark imparts a hypothetical cash value, even a heroic dignity, to the fussiness they probably acquired in toilet training.

The thing about text errors in the law is that natural language is highly redundant. You can transpose letters in a sentence or word, sow punctuation randomly, leave out the vowels: what’s left will ordinarily still convey the intended meaning. Errors induced by chance rarely create true ambiguity. Their disruptiveness is vexing when you are trying to create high art for a consumer’s pleasure, such as, say, a learned newspaper column. Usually they do not cost anyone money or alter history.

Colby Cosh, “At long last, milkmen deliver the punctuation scandal we’ve been waiting for”, National Post, 2017-03-22.