Forgotten Weapons

Published 30 Aug 2021http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.forgottenweapons.com

Today we have a rifle from a really neat forgotten corner of American military history. During World War One, the Pacific Northwest was the source of prime lumber, in particular Sitka Spruce that was ideal for aircraft production. The US military wanted that spruce for its own aircraft, and there was also massive demand from France and the UK for their production as well. As part of the American war effort, the Signal Corps (which oversaw military aviation) set about increasing spruce production severalfold.

The Corps sent a Colonel to investigate what would be necessary to do this, and he found that logging work was being significantly disrupted by labor union organizing, ranging from strikes to active sabotage. In response, the Army essentially created its own labor union, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen which both provided some of the labor reforms sought by groups like the IWW and also succeeded in massively increasing timber output for the war. The LLLL is a mostly-forgotten organization, and most of the documentation on it is from very left-wing organizations that paint it as a government attempt to quash labor rights. The reality appears to be far more nuanced, with several very legitimate reforms instituted in good faith. Unfortunately, the best reference on this period is completely out of print, Soldiers and Spruce: Origins of the Loyal Legions of Loggers & Lumberman by Harold Hyman (https://amzn.to/3lErrRC).

At any rate, part of the effort included the creation of the Spruce Production Division — 25,000 soldiers (mostly with backgrounds in logging and lumber) to Vancouver. They were seconded to private logging companies with Army-subsidized wages, but retained a military structure and officer corps. The Signal Corps purchased about 1,800 Winchester Model 1894 rifles in .30-30 caliber to arm a segment of the Division for security and military police type duties. Winchester 94s were in production and readily accessible, and the Division’s mission did not justify giving them Enfield or Springfield rifles needed by troops in Europe. These Winchesters were marked with a “US” property stamp and flaming bomb, and had serial numbers between 835,000 and 853,000 (specific numbers are not known because Winchester’s records form this period were destroyed). When the war ended, the guns (along with the Division’s other equipment) were sold as surplus, and they are found to this day in the Northwest. Many are in poor condition from decades of hard use, and they can be difficult to identify (and are also faked …) but they are a really neat artifact of a long-forgotten part of World War One history.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle 36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

December 30, 2021

The Army’s Labor Union: Winchester 94s for the Loyal Legion of Loggers & Lumbermen

December 1, 2021

QotD: When mere teaching isn’t enough, indoctrination takes over

There is no such thing as learning loss. Our kids didn’t lose anything [during the pandemic]. It’s okay that our babies may not have learned all their times tables. They learned resilience. They learned survival. They learned critical-thinking skills. They know the difference between a riot and a protest. They know the words insurrection and coup.

So says Cecily Myart-Cruz, president of the United Teachers Los Angeles union. A union representing 33,000 teachers and associated educational staff.

“Education is political”, says Ms Myart-Cruz, who boasts of her ability to act with near-impunity, and whose list of Intolerable Things includes cognitive testing, “structural racism”, border controls, policing, and the supposed “privilege” of parents who would like their children to actually learn things, including times tables. Our Mistress Of Higher Purpose struggles to comprehend why parents might object to their children’s education, even in basic skills, being supplanted by the nakedly self-serving and increasingly weird activism of the people paid to teach them those basic skills. Instead, she endorses claims that such objections must be driven by “white-supremacist thinking”.

David Thompson, “Activism Farms”, DavidThompson, 2021-08-31.

August 21, 2021

QotD: Why do government workers need unions?

So, umm, why does a worker for the state need a countervailing power to protect her from the state?

Sure, we can understand this if she’s working for the bastard capitalists. They merely want to maximise their profit and screw the workers while doing so – as we all know. But government is omniscient, omnipresent and omnibenevolent. It cannot be true that someone working for government is in need of protection from government. Because all those fine folks that make up government simply could not allow it to be that state workers don’t gain adequate wages.

Seriously, come on, this is the Progressive insistence. That getting government to do things saves us from the ravages we endure if the capitalists do them.

But now survey the actual American workplace. Unions in the private sector pretty much don’t exist any more. It is the government workforces that are unionised, making up the vast majority of union members in the country. From that pattern of union existence we have to conclude that government screws the workers rather more than the capitalists do. Otherwise why would people desire let alone need the protection of unions when working for government?

Tim Worstall, “The Public Union Proof That The Progressive State Doesn’t Work”, Expunct, 2021-05-11.

July 8, 2021

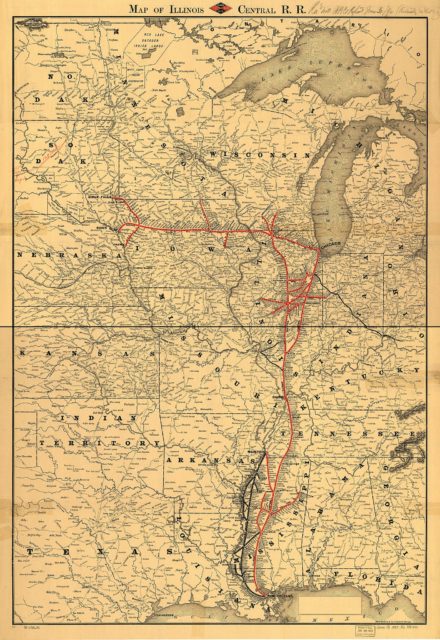

Fallen Flag — the Illinois Central Railroad

The IC (nicknamed the “Main Line of Mid-America”) was originally incorporated in 1836 to build a rail connection from Cairo to Galena with a branch to Chicago, but didn’t receive federal support until 1850 and the company was finally granted a charter in 1851. The IC was the first “land grant” railroad in the United States, and prominent Illinois politicians were deeply involved in the railroad (Senator Stephen Douglas and future President Abraham Lincoln). The line was completed in 1856 and the “branch” to Chicago rapidly became the busiest portion of the line. After the Civil War, the IC expanded out of Illinois into Iowa and then by acquisition and consolidation eventually reached Louisville, Kentucky and New Orleans, Louisiana with many branches and secondary lines throughout the eastern half of the Mississippi valley. In the 1880s, the IC also expanded north and west, reaching locations in Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Nebraska by the end of the century.

During the 1880s, the IC came under the control of E.H. Harriman and as a result were one of the railroads that were involved in the union actions that ran from 1911 until 1915. The IC and the other Harriman-controlled railways had existing contracts with the individual trade unions representing workers on each line, but the unions hoped to force the railways to recognize a “System Federation” of the separate unions that would negotiate as a single unit. The IC refused and hired strikebreakers to fill the positions vacated by striking union members — including many African-American men who would not normally have been allowed to work in those positions on southern railways. Sporadic violence in 1911 and 1912 resulted in the deaths of at least 12 men and 30 others were killed in a steam locomotive boiler explosion in San Antonio, Texas. It was generally seen as a failure by mid-1912, but the strike didn’t formally end until 1915. The unions tried again in 1922 in the Great Railroad Strike, which was an even larger attempt by the unions to operate as a single bargaining unit, and another ten people were killed during the conflict but it lasted only a couple of months and failed to achieve its aims.

Although the major portions of the system were in place by World War 1, there were some additional lines added through to the 1960s, merging or acquiring control of lines like the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley, the Gulf & Ship Island, the Chicago, St. Louis & New Orleans, the Alabama & Vicksburg, and the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific. George Drury picks up the story in mid-century:

In the 1950s and early ’60s IC purchased several short lines: former interurban Waterloo, Cedar Falls & Northern (jointly with the Rock Island through a new subsidiary, Waterloo Railroad); Tremont & Gulf in Louisiana; Peabody Short Line, a coal-hauler at East St. Louis, Ill.; and Louisiana Midland.

In 1968 Illinois Central acquired the western third — Nashville to Hopkinsville, Ky. — of the Tennessee Central when that financially ailing line was split among IC, Louisville & Nashville, and Southern.

Illinois Central Gulf

Illinois Central and parallel Gulf, Mobile & Ohio merged on August 10, 1972, to create the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad, a wholly owned subsidiary of Illinois Central Industries. GM&O was a likely merger partner for Illinois Central, as it was a north-south railroad through much the same area as IC. As part of the merger, ICG took over three Mississippi lines: Bonhomie & Hattiesburg Southern; Columbus & Greenville; and Fernwood, Columbia & Gulf.

The north-south lines of ICG’s map resembled an hourglass. Driving across Mississippi or Illinois from east to west, you could encounter as many as eight ICG lines. The former IC system converged at Fulton, Ky., and the former GM&O main line was less than 10 miles west of Fulton at Cayce.

[…]

On Feb. 29, 1988, the railroad changed its name back to Illinois Central, having divested itself of nearly all the former GM&O routes it acquired in 1972, when it added “Gulf” to its name. At the end of 1988 the Whitman Corp. (formerly IC Industries) spun off the railroad, which then dropped “Gulf” from the name, and in August 1989 control of the railroad was gained by the Prospect Group, which formerly controlled spinoff MidSouth Rail.

IC managers eventually turned their eyes west, to the Chicago, Central & Pacific, which it had sold in 1985. It saw CC&P’s route as a source of grain traffic and perhaps a way to get some of the coal moving east from Wyoming. In June 1996 IC purchased the CC&P. The line remains active.

In February 1998 Canadian National Railway agreed to purchase the IC, creating a 19,000-mile railroad. CN absorbed IC in July 1999, and IC lost its own identity within the CN system.

April 5, 2021

The 1919 Red Scare – the craziest year in American history

The Cynical Historian

Published 19 May 2016Many people have heard of the first Red Scare, but we should look at the year of 1919 more thoroughly. It’s probably the craziest one in American history.

Ann Hagedorn, Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919 (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2007). https://amzn.to/2NHIcaT

————————————————————

contribute to my Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorianLET’S CONNECT:

https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

————————————————————

wiki:

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included those such as the Russian Revolution. At its height in 1919–1920, concerns over the effects of radical political agitation in American society and the alleged spread of communism and anarchism in the American labor movement fueled a general sense of paranoia.The Scare had its origins in the hyper-nationalism of World War I as well as the Russian Revolution. At the war’s end, following the October Revolution, American authorities saw the threat of Communist revolution in the actions of organized labor, including such disparate cases as the Seattle General Strike and the Boston Police Strike and then in the bombing campaign directed by anarchist groups at political and business leaders. Fueled by labor unrest and the anarchist bombings, and then spurred on by United States Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s attempt to suppress radical organizations, it was characterized by exaggerated rhetoric, illegal search and seizures, unwarranted arrests and detentions, and the deportation of several hundred suspected radicals and anarchists. In addition, the growing anti-immigration nativism movement among Americans viewed increasing immigration from Southern Europe and Eastern Europe as a threat to American political and social stability.

Bolshevism and the threat of a Communist-inspired revolution in the U.S. became the overriding explanation for challenges to the social order, even such largely unrelated events as incidents of interracial violence. Fear of radicalism was used to explain the suppression of freedom of expression in form of display of certain flags and banners. The First Red Scare effectively ended in mid-1920, after Attorney General Palmer forecast a massive radical uprising on May Day and the day passed without incident.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #History #1919 #RedScare #SpanishFlu #Bolshevism #BlackSox #strikes #WoodrowWilson #LeagueOfNations #prohibition #suffrage

[Note: this was filmed in 2016 … I think 2020 has now taken the mantle of “craziest year”. Unless 2021 doubles down all the weirdness of 2020.]

March 30, 2021

QotD: Static societies and disruptive outsiders

In 1981, the social scientist Mancur Olson published his magisterial The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities. Olson had already won acclaim for The Logic of Collective Action, which explained why some groups received an outsize slice of the political pie. In his new book, Olson turned to the question of why nations fail. His thesis: nations lost dynamism when insiders managed to stack the rules against disruptive outsiders.

Stable societies with unchanged boundaries, Olson observed, “tend to accumulate more collusions and organizations for collective action over time.” Instead of accepting rules that encourage overall growth, these collusive organizations — trade groups and labor unions were paradigmatic examples — fight to keep what they have, slowing down “a society’s capacity to adopt new technologies and to reallocate resources in response to changing conditions,” thus reducing economic efficiency. Decline follows.

Olson pointed to Japanese stagnation under the Tokugawa shogunate, when, “before Admiral Perry’s gunboats appeared in 1854, the Japanese were virtually closed off from the international economy.” Ruling Japanese society, he writes, “were any number of powerful za, or guilds, and the shogunate or the daimyo often strengthened them by selling them monopoly rights.” The guilds “fixed prices, restricted production and controlled entry in essentially the same way as cartelistic organization elsewhere.”

A second example: Great Britain, “the major nation with the longest immunity from dictatorship, invasion and revolution” and, consequently, Olson explained, suffering “this century a lower rate of growth than other large, developed democracies.” In Olson’s view, the weak performance resulted from limits on change established by a “powerful network of special-interest organizations,” which included labor unions, industrial groups, and aristocratic cliques. By the 1970s, after the conservative government of Edward Heath fell in a losing battle with striking miners, many deemed Britain ungovernable. Olson contrasted the British situation with that of postwar Germany and Japan, where the chaos and destruction of wartime defeat wiped away established industrial and retail groups, leaving the field open to newcomers like Soichiro Honda or the Albrecht family (creators of international supermarket giant Aldi), who could work economic magic.

The word “ungovernable” was also used to describe New York in the 1960s and 1970s, when Mike Quill’s transit union ran roughshod over Mayor John Lindsay’s attempts to control public-sector wage growth. New York was a long-established city with lots of political collusion. The old Tammany Hall could broker deals to keep Gotham going, but Lindsay’s successor, Abe Beame, proved too weak to resist any special interest that wanted more spending or government favors. New York’s spending kept rising even as public services worsened, until bankruptcy loomed and public power wound up in the hands of the unelected Municipal Assistance Corporation. Thankfully, New York reformed itself economically, at least to some extent, under Mayors Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, as Britain did under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Sufficiently strong leaders can buck entrenched insiders.

Edward L. Glaeser, “How to Fix American Capitalism”, City Journal, 2020-12-13.

February 15, 2021

The current (and future) rash of newsroom purges

Some thoughts from The Line on why people like former New York Times science reporter Donald McNeil are being given the show trial treatment and why it’s not going to stop quickly:

The New York Times Building in New York City, 1 January, 2008.

Photo by Frieder Blickle via Wikimedia Commons.

The first issue, of course, is a steady weaponization of HR processes and unions. Vehicles intended to fix problems like unfair pay structures, workplace misconduct and lack of due process are being re-deployed as tools of ideological conformity — fuelled by healthy doses of personal dislike and professional resentment.

Make no mistake: there are bad people in journalism, as there are in any profession. Abusers should be rooted out, and there should always be clear processes in place to handle toxic personalities fairly, decisively and effectively. (“Fairly” isn’t a buzzword here — the accused must have rights, too.)

But there has also been a steady lowering of the bar as to what evils warrant an HR intervention. Every newsroom should be a safe place from abuse, harassment and violence — but not from ideas that are offensive. We recognize the entirely legitimate concerns of employees who are from marginalized groups about historic injustices, microaggressions and systemic power imbalances. But being in the world sometimes involves working with people who are simply insensitive assholes. Drawing the line between the merely difficult and the truly dysfunctional isn’t always easy.

Further, many of the complaints now being bandied about are strategic. They are being used to pummel terrified HR staffs and weak, ineffectual managers into compliance with ideological agendas. A staff at war with itself and ever-fearful of the axe is easier to silence and control. Owners have long understood this; it’s a grim irony that our peers have now decided to take up the hood and the blade.

These workplace revolts always boil down to an internal struggle for control. The very concept of where power rests is being challenged by those who think the traditional way of running newsrooms is as obsolete as a classifieds page. Uprisings are about who decides institutional values, and who gets to enforce those values. An entire class of leaders needs to wake up to the fact that they’re three campaigns deep into a battle for their own legitimacy. And they’re losing.

That brings us to the third issue: management. We’ve said this before, but managers need to show some spine. The most consistent theme in all these newsroom eruptions is management either lacking the confidence to assert its authority, or hesitating to do so just long enough to make things worse. Too many leaders have been selected for their affability rather than their toughness. We at The Line suspect this is no accident. Powerful editors, necessary for effective management of staff, are inconvenient for owners intent on slashing said newsrooms. The kind of people who’d be most effective at crushing the odd staff rebellion also annoy the suits. So instead, we get nice people — truly nice people — who know the right folks and subscribe to the right politics, and shy away from embarrassment, conflict, and loss of status. They’re marks.

February 2, 2021

The History of Hollywood

The Cynical Historian

Published 3 Sep 2020This episode is about the history of Hollywood, and it’s quite a long one. This is part 9 in a long running series about California history.

————————————————————

references:

Bernard F. Dick, Engulfed: The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001). https://amzn.to/3f2Yb0SHollywood’s America: United States History Through its Films, eds. Mintz, Steven and Randy Roberts (St. James, N.York: Brandywine Press, 1993). https://amzn.to/2tZIoJT

Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Atheneum Books, 1992). https://amzn.to/2KX0jI2

Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era, (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1985). https://amzn.to/2VPTbVX

————————————————————

Support the channel through PATREON: https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorian

or by purchasing MERCH: teespring.com/stores/the-cynical-hist…LET’S CONNECT:

Twitch: https://www.twitch.tv/cynicalhistorian

Discord: https://discord.gg/Ukthk4U

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

Subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/CynicalHistory/————————————————————

Wiki: By 1912, major motion-picture companies had set up production near or in Los Angeles. In the early 1900s, most motion picture patents were held by Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey, and filmmakers were often sued to stop their productions. To escape this, filmmakers began moving out west to Los Angeles, where attempts to enforce Edison’s patents were easier to evade. Also, the weather was ideal and there was quick access to various settings. Los Angeles became the capital of the film industry in the United States. The mountains, plains and low land prices made Hollywood a good place to establish film studios.

Director D. W. Griffith was the first to make a motion picture in Hollywood. His 17-minute short film In Old California (1910) was filmed for the Biograph Company. Although Hollywood banned movie theaters — of which it had none — before annexation that year, Los Angeles had no such restriction. The first film by a Hollywood studio, Nestor Motion Picture Company, was shot on October 26, 1911. The H. J. Whitley home was used as its set, and the unnamed movie was filmed in the middle of their groves at the corner of Whitley Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard.

The first studio in Hollywood, the Nestor Company, was established by the New Jersey–based Centaur Company in a roadhouse at 6121 Sunset Boulevard (the corner of Gower), in October 1911. Four major film companies – Paramount, Warner Bros., RKO, and Columbia – had studios in Hollywood, as did several minor companies and rental studios. In the 1920s, Hollywood was the fifth-largest industry in the nation. By the 1930s, Hollywood studios became fully vertically integrated, as production, distribution and exhibition was controlled by these companies, enabling Hollywood to produce 600 films per year.

Hollywood became known as Tinseltown and the “dream factory” because of the glittering image of the movie industry. Hollywood has since become a major center for film study in the United States.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #history #Hollywood #California

December 30, 2020

This is why the word “unexpectedly” gets such a workout in media these days

David Warren on “unexpectedly” negative results from policies born of virtue-signalling “good intentions” by self-styled progressives:

The expression, “unintended consequences,” is a charitable dodge. It is what old-fashioned, polite, civic-minded people say about the fallout from progressive social policies. It implies that their authors have overlooked something, or made some innocent mistake. For unfortunately, the policies do the exact opposite of what was promised. Surely the “reformers” didn’t mean to force decent, reasonable people to do things that any decent, reasonable person would consider to be satanic. Yet somehow, that was the result.

By contrast, these reformers despise the tactics of the bourgeois. Rather than argue, they prefer to drown out their opponents with slogans. Rather than coherently reply, they characterize any asking questions as “fascist,” “misogynist,” “racist,” “hate criminals,” &c. Those who have exposed scandals are personally smeared, slandered, doxxed. This isn’t new. It is the way the Left has always “debated,” going back long before Lenin. Once they have the police working for them, opponents get the knock in the middle of the night.

There are, incidentally, two kinds of “reform,” corresponding to the two political persuasions. One happens without planning, and is an organic response to things no longer working properly. Try, in good faith, to make the old system work, and it will subtly change. The “problems” fix themselves, when they are allowed to. The other kind is “reform” according to a theory. A huge, mostly imaginary “problem” is created, so a “solution” may be imposed. Every tool must be applied, to get everyone onside for the task: fake news, fake science, fake history, and miscellaneous fakery. For as every godless person knows, “the end justifies the means.”

Luckier than most, raised in “liberal” environments, I was able to discern this from an early age. By chance I acquired many friends who were refugees from Communist (especially Soviet-occupied) countries. But it was not just that. Having been trained counter-culturally, by non-conformist “classically liberal” teachers, and also having learnt to read for myself, I was already fairly alert. The clincher for me was a native disposition, not only to think independently, but to resist being a putz. It was not in my nature to assume that the enemies of real liberalism (which requires honesty) had good intentions. Reason, and experiment, demonstrated that they had not.

For instance, I early realized that leftwing factions formed a Party of Privilege. Every policy they advanced favoured individuals with relatively more wealth and power, against individuals with less. Unions were a good example. They represented the better-paid. The labour laws they advocated were designed to exclude the young and the poor from labour-market competition. They secured the allegiance of thuggish union members through crassly self-interested schemes. They opposed legitimate rewards for labour; for skill and hard work. Instead they enforced universal mediocrity, and punished intelligent enterprise. Legitimate labour interests, once represented by cooperative and self-managing guilds, were replaced by the interests of (untalented) union organizers.

November 26, 2020

Deport All Anarchists! – The Palmer Raids | BETWEEN 2 WARS: ZEITGEIST! | E.05 – Harvest 1919

TimeGhost History

Published 25 Nov 2020The First World War has been over for a year, and the modern era plows ahead. But so does fear and paranoia. In America, the Red Scare goes into overdrive.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Indy Neidell and Francis van Berkel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell and Francis van Berkel

Image Research by: Daniel Weiss and Spartacus Olsson

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations:

Daniel Weiss – https://www.facebook.com/TheYankeeCol…Sources:

Some images from the Library of CongressSome Soundtracks from Epidemic Sound, ODJB, Edward Elgar, Richard Strauss and Pietro Mascagni:

– “One More for the Road” – Golden Age Radio

– “Dawn Of Civilization” – Jo Wandrini

– “Deviation In Time” – Johannes Bornlof

– “Easy Target” – Rannar Sillard

– “Dark Beginning” – Johan Hynynen

– “Steps in Time” – Golden Age Radio

– “Tiger Rag” – ODJB

– “Cello Concerto” – Edward Elgar

– “Pomp and Circumstance” – Edward Elgar

– “Die Frau ohne Schatten: Act III” – Richard Strauss

– “Cavalleria Rusticana” – Pietro Mascagni

– “What Now” – Golden Age RadioArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

November 5, 2020

America on the Brink of Revolution? | BETWEEN 2 WARS: ZEITGEIST! | E.02 – Winter 1919

TimeGhost History

Published 4 Nov 2020There is revolution and fear of revolution throughout the world in the winter of 1919. But cultural and technological revolutions are also bringing hope to many. A new age of Jazz and Cinema is about to reach America and Europe.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Indy Neidell, Francis van Berkel, and Spartacus Olsson.

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell, Francis van Berkel, and Spartacus Olsson.

Archive Research: Daniel Weiss

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations:

Daniel Weiss – https://www.facebook.com/TheYankeeCol…

Mikołaj Uchman

Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/Sources:

From the Noun Project:

– Money by Gilberto

– lightbulb By Maxim KulikovSoundtracks from Epidemic Sound and ODJB:

– “One More for the Road” – Golden Age Radio

– “The Last Journey” – Line Neesgaard

– “Tiger_Rag” – ODJB

– “Not Safe Yet” – Gunnar Johnsen

– “Please Hear Me Out” – Philip Ayers

– “Dark Shadow” – Etienne Roussel

– “The Inspector 4” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “I Won’t Give You Up” – Almost Here

– “The Charleston” – Macy’s Voice

– “Defeated” – Wendel SchererArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 days ago (edited)

As in life, this series will always be a curious balance of light and dark. In the winter of 1919, one Parisian might have tickets to see the Original Dixieland Jass Band while their neighbour lies destitute after the war, and a well-to do man in Glasgow might be at the cinema while tanks rolls into his city to quell industrial unrest.Troubled and fascinating times then and troubled fascinating times now here in 2020. All of us here at TimeGhost hope that all of you are healthy and staying safe. And hey, if you need some entertainment to pass the time, you can find plenty of Between 2 Wars episodes alongside WW2 In Real Time and BIO Specials!

September 15, 2020

QotD: Racism and the minimum wage

During South Africa’s apartheid era, racist unions, which would never accept a black member, were the major supporters of minimum wages for blacks. In 1925, the South African Economic and Wage Commission said, “The method would be to fix a minimum rate for an occupation or craft so high that no Native would be likely to be employed.” Gert Beetge, secretary of the racist Building Workers’ Union, complained, “There is no job reservation left in the building industry, and in the circumstances, I support the rate for the job (minimum wage) as the second-best way of protecting our white artisans.” “Equal pay for equal work” became the rallying slogan of the South African white labor movement. These laborers knew that if employers were forced to pay black workers the same wages as white workers, there’d be reduced incentive to hire blacks.

South Africans were not alone in their minimum wage conspiracy against blacks. After a bitter 1909 strike by the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen in the U.S., an arbitration board decreed that blacks and whites were to be paid equal wages. Union members expressed their delight, saying, “If this course of action is followed by the company and the incentive for employing the Negro thus removed, the strike will not have been in vain.”

Our nation’s first minimum wage law, the Davis-Bacon Act of 1931, had racist motivation. During its legislative debate, its congressional supporters made such statements as, “That contractor has cheap colored labor that he transports, and he puts them in cabins, and it is labor of that sort that is in competition with white labor throughout the country.” During hearings, American Federation of Labor President William Green complained, “Colored labor is being sought to demoralize wage rates.”

Walter E. Williams, “Minimum Wage and Discrimination”, Creators Syndicate, 2017-02-08.

August 27, 2020

QotD: Racism and the minimum wage

Minimum-wage laws can even affect the level of racial discrimination. In an earlier era, when racial discrimination was both legally and socially accepted, minimum-wage laws were often used openly to price minorities out of the job market.

In 1925, a minimum-wage law was passed in the Canadian province of British Columbia, with the intent and effect of pricing Japanese immigrants out of jobs in the lumbering industry.

A Harvard professor of that era referred approvingly to Australia’s minimum wage law as a means to “protect the white Australian’s standard of living from the invidious competition of the colored races, particularly of the Chinese” who were willing to work for less.

In South Africa during the era of apartheid, white labor unions urged that a minimum-wage law be applied to all races, to keep black workers from taking jobs away from white unionized workers by working for less than the union pay scale.

Some supporters of the first federal minimum-wage law in the United States — the Davis-Bacon Act of 1931 — used exactly the same rationale, citing the fact that Southern construction companies, using non-union black workers, were able to come north and underbid construction companies using unionized white labor.

These supporters of minimum-wage laws understood long ago something that today’s supporters of such laws seem not to have bothered to think through. People whose wages are raised by law do not necessarily benefit, because they are often less likely to be hired at the imposed minimum-wage rate.

Thomas Sowell, “Why racists love the minimum wage laws”, New York Post, 2013-09-17.

July 18, 2020

QotD: Peace can also be the health of the state

War, we libertarians are fond of telling each other, is the health of the state. Peruse the most recent posting here by our own WW1 historian, Patrick Crozier, to see how we often think about such things. So, what about that increasingly obtrusive and kleptocratic Brazilian state that has been putting itself about lately, stirring up misery and libertarianism? There have been no big wars to make the Brazilian state as healthy as it now is, and especially not recently. What of that?

The story Bruno Nardi told made me think of the book that explains how peace is also the health of the state, namely Mancur Olson’s public choice theory classic, The Rise and Decline of Nations. It is years since I read this, but the story that this book tells is of the slow accumulation and coagulation of politics, at the expense of mere business, as the institutions of a hitherto thriving nation gang up together to form “distributional coalitions” (that phrase I do definitely recall). The point being that if you get involved in a war, and especially if you lose a war, the way Germany and Japan lost WW2, that tends to break up such coalitions.

The last thing on the mind of a German trade unionist or businessman, in 1946, was lobbying the government for regulatory advantages or for subsidies for his particular little slice of the German economy. Such people at that time were more concerned to obtain certificates saying that they weren’t Nazis, a task made trickier by the fact that most of them were Nazis. Olson’s way of thinking makes the post-war (West) German and then Japanese economic miracles, and the relative sluggishness of the British economy at that time, a lot more understandable. Winning a war, as Olson points out, is not nearly so disruptive of those distributional coalitions, in fact it strengthens them, as Crozier’s earlier posting illustrates.

Brian Micklethwait, “The view from Brazil is that peace is also the health of the state”, Samizdata, 2018-04-13.

May 26, 2020

“No more pencils, no more books…”

In the latest edition of the Libertarian Enterprise, Sean Gabb considers the demands from the British government to quickly re-open the schools over the concerns of the educational unions and administrations:

The latest turn in an increasingly dull coverage of the Coronavirus panic is a proposed reopening of the schools. The Government wants them open as soon as possible for at least some of their students. The teaching unions are bleating that no one should go back until their members can be sure of not catching anything. The headmasters are worried about compliance with the social distancing rules. As a conservative of sorts, I think I am supposed to side with the Government and the pro-Conservative journalists — denouncing the teachers as a pack of idlers where not cowards, and insisting that those factories of essential skills must be set back in full production before the summer holidays. Of course, my settled view as a libertarian is that the teaching unions deserve all the support I have never so far given them. The schools must remain closed until no one is in any danger of so much as an attack of hay fever. The schools have been largely closed since the end of March. The longer they stay largely closed, the better. Best of all if they never reopen — or never reopen as they have been since attendance was made compulsory at the end of the nineteenth century.

I quote John Stuart Mill on compulsory schooling:

A general State education is a mere contrivance for moulding people to be exactly like one another: and as the mould in which it casts them is that which pleases the predominant power in the government, whether this be a monarch, a priesthood, an aristocracy, or the majority of the existing generation; in proportion as it is efficient and successful, it establishes a despotism over the mind, leading by natural tendency to one over the body.

(On Liberty, 1859, Chapter 5, “Applications.”)This has always been the case in some degree. The spread of state schooling in England after 1870, and particularly after it was made compulsory in 1880, and then extended in 1902, is probably inseparable from the nationalist hysteria that drove our participation in the Great War. It also may explain the perverse belief, general until the 1970s, in the unique goodness and honesty of our ruling class. This being said, reasonable patriotism is to be encouraged; and, compared with others, our ruling class was not until recently so bad. A further point is that compulsory state schooling used to be reasonably effective at giving the mass of people a basic education. By 1960, most people were literate and numerate. They could spell and write grammatical prose. They had some exposure to the English classics, and the means of exploring these to greater depth if they wished. They had some understanding of history and the sciences. You can tell much about the quality of a people by examining what is read and watched. Looking at the popular arts in England during much of the twentieth century explains why this passage in On Liberty was less often discussed than his arguments for freedom of speech. Mill was right in the abstract. He could be shown to be right in certain particulars. But the evils of compulsory state schooling were mostly potential.

All this, however, is in the past. Since about 1980, schooling of all kinds has been made into a concerted means of indoctrination. The cultural leftists have captured both the classrooms and the curriculum. I will not elaborate on this claim. Some will argue over terminology, some over the merits of the capture, but hardly anyone denies the broad fact. One of the main functions of modern schooling is to bring about and to protect a radical departure from the old intellectual culture of this country.

Much of this departure has been achieved by preaching in the classroom. But it is supplemented by a growing bureaucracy of surveillance. The teachers themselves are watched, and they can be punished for dissenting from the established discourse. There is, for example, the Government’s Prevent strategy, which applies to the whole state machinery. Its purpose is to identify and root out anyone defined as a “political extremist.” Anyone identified as such is effectively banned from working with children and young people, and probably in the state sector as a whole.