At all levels of American football below pro, the “option” is a major facet of the game. This is an offensive play where the quarterback can either run the ball himself, pitch it to another player, or throw it downfield, as he thinks best. It certainly helps if the quarterback is a strong-armed, accurate passer, but the key criterion here is speed. If you get defenders cheating up in order to stop the run, you don’t have to be as strong or accurate with your throws. What matters is that the QB can pass — meaning, he can throw it X yards downfield, within a few yards’ radius of a given spot — not how often he does so. The closer he can get it to the spot, and the further downfield that spot is, the better, but so long as he’s in the vicinity the option system works well.

This starts very, very early in a player’s career. The lower down the skill ladder you go, the more prominent the “option” offense. In “Pop Warner” leagues — kids below age 12, basically — the option pretty much IS the offense, since few kids can throw the ball very far, much less with accuracy. Throwing a football with both velocity and accuracy is extremely difficult, and it doesn’t help that sound throwing mechanics feel brutally unnatural — you know you’re doing it right when it feels like your shoulder is going to pop out of its socket at the very instant your elbow ligaments snap and hit you in the face … which, unfortunately, is exactly what it feels like when you’re doing it wrong, and your shoulder IS about to pop out at the same moment your elbow ligaments snap.

What happens, then, is that kids generally learn how to throw with very poor form … but coaches generally aren’t going to correct them, either because they don’t know the proper mechanics themselves, or because they are focused exclusively on winning games. Who cares if little Kayden, Brayden, or Jayden is going to blow his arm out hucking it like that when he hits high school? That’s Coach Smith’s problem. All that matters now is that he can get it to X spot with radius Y.

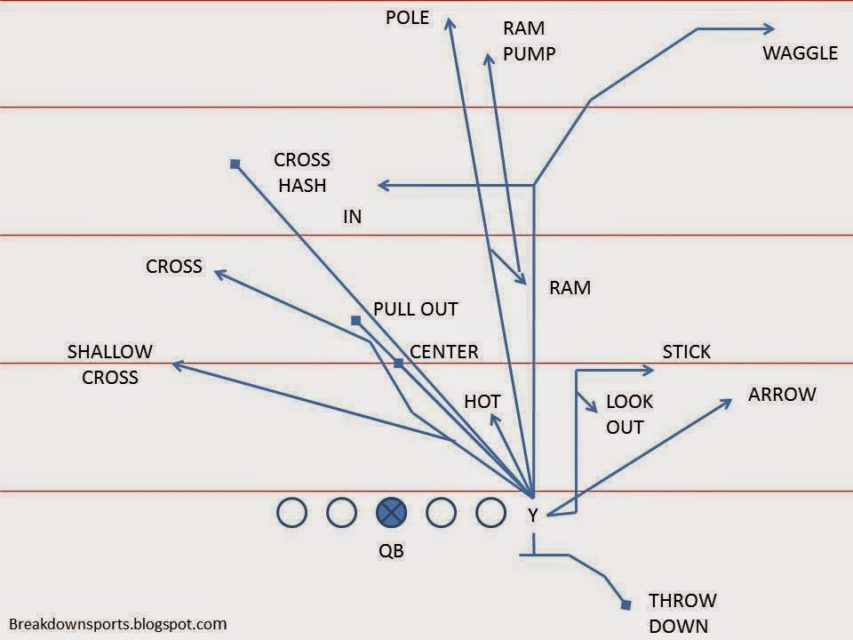

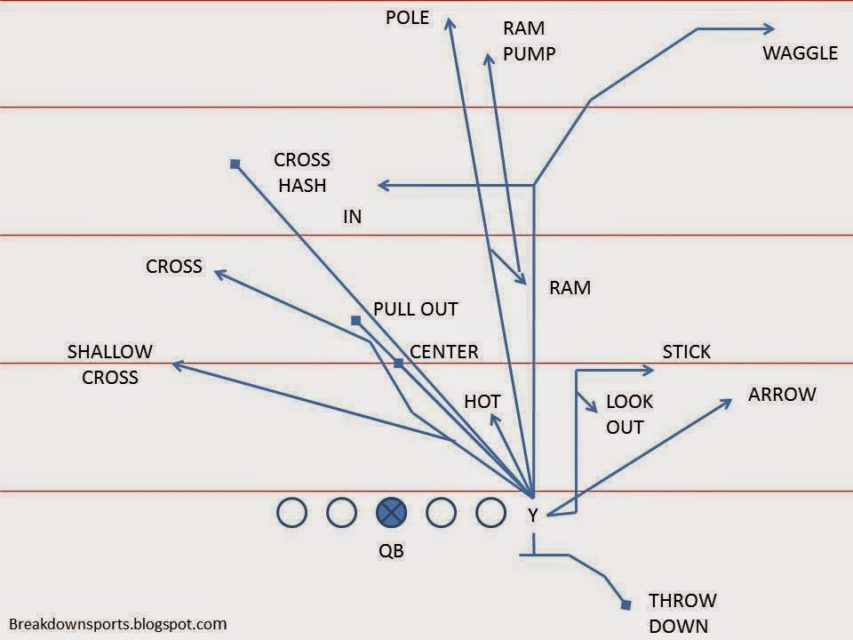

Thus the possible career path of any kid who can throw a football reasonably well quickly diverges. If he’s too slow to run the option effectively, his coaches will try to turn him into an “air raid” style quarterback, which means he throws on every play, mechanics be damned, because we need to win now, and what the hell, he can get it there, can’t he? But even the “air raid” style of play is enormously more difficult to coach, because that means you need to be able to coach a whole corps of wide receivers to run a whole bunch of increasingly complex routes. Here, look:

That’s what’s known as a “route tree”, and all of your receivers — five guys, usually, on every play, plus their backups — need to know how to run every one of them, every time. Which means your playbook is going to be huge, because you (theoretically, anyway) need a play for each one of those routes, for each receiver on the field. And obviously your quarterback has to have something going on upstairs, because he needs to memorize five different guys’ routes for every single play, plus audibles and checkdowns (changing any given player’s route, or even the entire play, on the fly), and so on.

I’m sure y’all see where I’m going with this, but it’s important to note that the key selection — whether a given kid shall be an “option” quarterback, or an “air raid” quarterback — has been made by someone else, much lower on the skill ladder. It would be great if one and the same kid could do both to a high degree of skill, but since human neurons apparently don’t work like that, it’s natural for everyone involved to take the path of least resistance.

And again, I’m not blaming coaches for this. Forget things like “getting fired for losing too many games”, and just consider the sheer amount of work. Stipulating for the sake of argument that you’ve got 50 man-hours in a week to get ready for a game, how do you best allocate them? Getting your QB to throw with proper mechanics alone probably takes a significant chunk of that time, and even though he’ll have to do a lot of it on his own — throwing passes at a tire in the backyard until his arm feels ready to fall off — you’re still spending a LOT of time on something that will make no appreciable difference to the game’s outcome this Friday night. And then throw in the other stuff — how much time does it take just to “install” (as the term d’art is) a game plan that has all those routes in it, much less coaching all the receivers up to where they can run them all?

Nah, brah. Just hand Jonquarious the ball and let him run it, and if he has to huck it downfield every now and again, let him do it his way. Again, this will make no difference at all to the outcome of this week’s game — he’ll either run it or he won’t; make the throw or not — but it frees up a lot of man hours to do all the other stuff a coach has to do that we haven’t talked about yet, such as defense.