I won’t attempt to recap here the many arguments that have been made recently about whether and how our society is stagnating. You could read this book or this book or this book. Or you could look at how economic productivity has stalled since 1971. Or you could puzzle over what else happened in 1971. Or you could read Patrick Collison’s list of how fast things used to happen, or ponder how practically every new movie these days is a sequel, or stare in shock at declines in scientific productivity. This new book by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber starts with a survey of the most damning indicators of stagnation, moves on to suggest some underlying causes, and then suggests an unexpected way out.

Their explanation for our doldrums is simple: we’re more risk averse, and we don’t care as much about the future. Risk aversion means stagnation, because any attempt to make things better involves risk: it could also make things worse, or it could fail and turn out to be a waste of time and money. Trying to invent a crazy new technology is risky, going into consulting or finance is safe. Investing in unproven startups or speculative bets is risky, investing in index funds is safe. Trying to overturn the scientific consensus is risky, keeping your head down and publishing papers that don’t say anything is safe. Producing challenging new art is risky, spewing an endless stream of Marvel superhero capeshit is safe. Even if, in every case, the safe option is the “rational” choice for an individual actor in maximin expected value terms, the sum total of these individually rational choices is a catastrophe for society.

So far this is a lame, almost tautological, explanation. Even if it’s all true, we still haven’t explained why people are so much more fearful of failure than they used to be. In fact, we would naively assume the opposite — society is much richer now, social safety nets much more robust, and in the industrialized world even the very poor needn’t fear starvation. In a very real sense, it’s never been safer to take risks. Failing as a startup founder or academic means you experience slightly lower lifetime earnings,1 while, in the great speculative excursions of the past, failure (and sometimes even success) meant death, scurvy, amputations, destitution, children sold into slavery or raised in poorhouses — basically unbounded personal catastrophe. And yet we do it less and less. Why?

Well, for starters, we aren’t the same people. Biologically, that is. We’re old, and old people tend to be more risk-averse in every way. Old people have more to lose. Old people also have less testosterone in their bloodstream. The population structure of our society has shifted drastically older because we aren’t having any children. This not only increases the relative number (and hence relative power) of older people, it also has direct effects on risk-aversion and future-orientation. People with fewer children have all their eggs in fewer baskets. They counsel those kids to go into safe professions and train them from birth to be organization kids. People with no children at all are disconnected from the far future, reinforcing the natural tendency of the elderly to favor consumption in the here and now over investment in a future they may never get to enjoy.

Old age isn’t the only thing that reduces testosterone levels. So does just living in the 21st century. The declines are broad-based, severe, and mysterious. Very plausibly they are downstream of microplastics and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The same chemicals may have feminizing effects beyond declines in serum testosterone. They could also be affecting the birth rate, one of many ways that these explanations all swirl around and flow into one another. Or maybe we don’t even need to invoke old age and microplastics to explain the decline in average testosterone of decisionmakers in our society. Many more of those decisionmakers are women, and women are vastly more risk-averse on average.2

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Boom, by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-11-11.

1. And given the logarithmic hedonic utility of additional money and fame, that hurts even less than it sounds like it would.

2. If you’re too lazy to read Jane’s review of Bronze Age Mindset but just want the evidence that women are more cautious and consensus-seeking than men on average, try this and this and this for starters.

February 16, 2025

QotD: Why we’re stagnating

February 13, 2025

QotD: Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism fails both on its own terms, and in the implementation. On its own terms, because we simply can’t account for all the variables. I use the example of billiards: The math is simple enough behind any given billiard shot, but once you introduce obvious real world variables like imperceptible imperfections in the felt of the table, the balls themselves, the cue … plus the inability of human muscles to consistently apply the necessary force in just the right way … your average PhD physicist should be a much better pool player than, say, your average barfly, but the reality is far different. How much more complex is an entire living system, than a pool table?

Social Darwinism fails in practice for the most obvious reason: You can’t practice it with the necessary consistency without massive State intervention, and what kind of fool would give a State, any State, that power? It has been tried, 1933-45 being the most prominent example, and it didn’t go well.

Severian, “The Experiment”, Founding Questions, 2021-09-25.

January 10, 2025

QotD: The “bottle service” model as a “douchebag Potlatch”

Gabriel: So far we’ve been discussing bottle service from the consumer’s point of view as a potlatch, but the core of the book is that it requires an enormous amount of extremely convoluted work to mobilize models as a sort of rent-an-entourage to be guests at the potlatch. Veblen observed that one of the functions of dependents, and indeed the primary function of dependents with little or no functional purpose, is to consume beyond what a rich man could consume himself and thereby demonstrate the rich man’s wealth and power. A Wall Street bro can probably consume a lot more alcohol than a woman with a body mass index of 18, but several underweight women at the bro’s table can considerably expand the amount of alcohol that the table can collectively consume. The distinctive feature of bottle service is that rather than the guests being either the host’s long-standing dependents or the host’s frenemy and the frenemy’s long-standing dependents as in a classic potlatch, the models are strangers to the host and their presence is arranged by the club, which subcontracts this to party promoters. I suppose this isn’t totally unprecedented since the synoptic gospels’ parable of the feast (Matthew 22 and Luke 14) also involves mobilizing a bunch of randos to benefit from the host’s largesse; but (a) the host in the parable relied on randos as a substitute when his regular dependents blew off his invitation, and (b) the parables aren’t intended to be realistic stories so aren’t good evidence than an actual 1st century AD host would behave this way.

As to whether I’ve gotten a grant to pay for bottle service, mercifully no. I have had dinner with a (former) model, but it was Ashley herself at the kind of restaurant that occasionally has a hedge fund Powerpoint deck critiquing its management go viral. It was a decent hour, both of us were completely sober, there was no party promoter arranging the meeting, and there was no EDM played at OSHA-violation decibel levels. My idea of a good time is a lucid conversation with a smart friend, such as both that occasion and this email exchange, whereas I’d pay a good amount of money to avoid getting extremely drunk and staying out until dawn in an environment too loud for conversation.1 However I salute Ashley for doing so and thereby providing us with this book. The most I’ve had to suffer for my scholarship is writing response memos to annoying reviewer questions, or struggling with merge errors whilst munging data files.

And yet, contrary to my own taste, the people at the night clubs are paying a lot of money and/or waiting in line to get in, so obviously they seem to think it is appealing. I don’t think we can call this false consciousness either. Ashley is very clear that part of the reasons the models go to the clubs is as a favor to the promoters (much more on that later), but part of it is that a lot of models think going to a famous night club is really glamorous and cool. I’m tempted to say this is just de gustibus non disputandum, but just shrugging at taste is kind of a cop out for a sociologist since one of our mandates is to explain socially patterned taste.

I think a key explanation for what’s going on is Girard’s mimetic desire. The club is glamorous because there’s a long line of people outside waiting to get past the velvet rope. The women are beautiful because everyone agrees that tall skinny women are beautiful, even though in other contexts a lot of men (including the promoters) are more attracted to the kind of shorter curvier women who are barred entry to the club as “midgets”. Everyone and everything in the world of models and bottles that is desirable is desirable primarily because they or it are desired by others.

John: I’ve never read a fashion magazine or watched a runway show, so I just naively assumed that models were stunningly attractive and feminine. But as Mears points out, the models are not actually to most men’s tastes. They tend to have boyish figures and to be unusually tall.2 Is this because the fashion industry is dominated by gay men, who gravitate towards women who look like teen boys? Whatever the origins of it, there is a model “look”, and the industry has slowly optimized for a more and more extreme version of it, like a runaway neural network, or like those tribes with the rings that stretch their necks or the boards that flatten their skulls. There’s actually a somewhat uncanny or even posthuman look to many of the models. The club promoters denigrate women who lack the model look as “civilians”, but freely admit that they’d rather sleep with a “good civilian” than with a model. The model’s function, as you say, is as a locus of mimetic desire. They’re wanted because they’re wanted, in a perfectly tautological self-bootstrapping cycle; and because, in the words of one promoter: “They really pop in da club because they seven feet tall”.

The men don’t want to sleep with the models, and by and large they don’t. This leads directly to one of the most jaw-dropping insights in the entire book: the models are a potlatch of sorts too. The men are buying thousand dollar bottles of champagne and dumping them out on the floor, destroying economic value just to show that they can. And likewise, they’re surrounding themselves with dozens of beautiful women and then not sleeping with them. A potlatch of female beauty, sexuality, and reproductive potential — flaunting their wealth by hoarding women and conspicuously declining to enjoy their company, but at the same time denying them to every other man. An anti-harem.

Actually, you know what else the models remind me of? Medieval jesters. There was a point in the 15th century when every ruler in Europe had to have a dwarf in his entourage — not because there was anything intrinsic or valuable about very short men, but just because it was rare. The first guy did it to show that he was a big enough deal to have something expensive and hard to find, and then everybody else started doing it because it was the thing to do. (When dwarfs became too commonplace, the status symbols got weirder.) I think model phenotype is a little bit like that — desirable because it is rare, and because gathering and showcasing all these rare objects is a way to demonstrate your wealth and power.

John Psmith and Gabriel Rossman, “GUEST JOINT REVIEW: Very Important People, by Ashley Mears”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-03-04.

1. Another interesting work of scholarship on partying is Minjae Kim’s work on Korean work team binge drinking. Minjae shows that people go binge drinking because most of them hate it and thus it serves as a costly signal of loyalty.

2. In fact, an unusually high proportion of models are intersex individuals with a Y-chromosome and androgen insensitivity syndrome.

August 20, 2024

Folk tale fictions about childbirth in “traditional cultures”

Jane Psmith finds that “everyone” has been doing certain “traditional” things during and after childbirth that she somehow wasn’t informed about until just a short while ago:

I just had a baby, which means I have once again been immersed in a sea of advice about how “traditional cultures” do things. And miraculously, every single kid, I discover some new practice I’ve never heard of but that apparently just everyone did until about five minutes ago. This time it was vaginal steaming. (Don’t Google, it’s exactly what it says on the tin.)

Which cultures, exactly? Oh, you know … the traditional ones, the ones whose folk wisdom is untrammeled by Western medicalization, where the pregnant woman is treated to the most nutritious foods, birth is a joyous event surrounded by supportive kin, the new mother puts her baby to the breast the minute he’s born, and she’s waited on hand-and-foot in bed for a month afterwards. So, you know, not the Ngongo of central Africa, who forbid women from eating meat, or the Netsilik Inuit or !Kung, both of whom send laboring women off to give birth in silent isolation, or any of the peoples from Fiji to northern Alberta who delay nursing for days … In fact, you might be excused if you began to suspect that the real measure of how “traditional” a culture is boils down to how much it resembles the practices of crunchy WEIRD people. You might even, if you had a nasty suspicious frame of mind, conclude that all this discussion of “traditional cultures” is just a disguised way of asserting our own preferences.

None of which is actually unique to the babies. (I’ve written about the babies before.) It’s not even unique to our era. The idea that we have been corrupted by civilization, that more primitive societies lead purer, nobler, more harmonious lives and enjoy access to truths and virtues we have lost, goes back millennia.1 And so, naturally, does the practice of using the supposed superiority of those other cultures as clubs to beat our own. Tacitus’ Germania, for instance, is a fun read if borderline useless as a source on the actual Germanic tribes — but it’s a wonderful guide to the angst of the early Empire and the pervasive fear that greed, luxury, and ambition had replaced the nobility, valor, and honor that had once characterized the Romans. Nowadays, of course, no one writes about the barbarians’ fides and virtus; instead you’ll get paeans to their idyllic existence lived in harmony with nature, their peaceful sense of community, and probably their joyful embrace of gender and sexual diversity. But either way, most of the books about small-scale societies are actually books about us and what the people writing the books think we lack.

Even professional anthropologists tend to assume that small-scale (this is a polite way of saying “primitive”) societies are more satisfying, meaningful, and fulfilling than complex ones. But in their case it goes hand in hand with another, allied assumption: that these societies have developed beliefs, practices, and institutions that work well for them. After all, the thinking goes, we know that people change their tools and their behavior when their environment changes, abandoning anything that no longer serves their needs and adopting new ways of life. Therefore, anything they haven’t abandoned must be somehow adaptive. Sure, these “primal communities” might do things that seem odd to us — things like torture, infanticide, ceremonial rape, cannibalism, and so forth — but they must serve some useful function or they wouldn’t have persisted. Thus, for example, the classic ethnography of the Navajo argues that their overwhelming fear of witchcraft, which led to pervasive anxiety, a hypochondriacal obsession with magical curing rituals, and of course regular violence perpetrated against suspected witches, actually had great benefits because it allowed the Navajo direct their stress and hostility at marginal members of the community and “keep the core of the society solid”.

The problem with this framework becomes obvious as soon as you mentally translate from some strange foreigners with funny (or no) clothes to, say, a business in the industrialized world. (Which can easily be larger than the kind of small-scale society that interests anthropologists.) No one would ever say, “Well, sure, the leadership of this company allows their mediocre employees to bully their highly productive peers out of the department so they do better in the stack ranking, but the company hasn’t gone bankrupt so it must be a savvy business move. Probably the solidarity created by banding together to surreptitiously delete someone else’s code enhances productivity more than losing a 10x engineer detracts from it …” But this is exactly what anthropologists (professional and armchair) are tempted to do when they set out to understand and explain another culture. Yes, sometimes apparently bizarre behavior contains a deep and hidden wisdom, but sometimes it’s just messed up.

That’s the case the late UCLA anthropologist Robert Edgerton set out to make in Sick Societies: that some primitive societies are not actually happy and fulfilled, that some of their beliefs and institutions are inadequate or actively harmful to their people, and that some of them are frankly on their way to cultural suicide. The mere fact that people keep doing something doesn’t mean it’s actually working well for them, but just as the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent, your society can stay dysfunctional longer than you can stay alive.

1. At least in the Occident. My informant tells me that the Noble Savage is a less common trope in, say, China. Maybe the Blue savages are just less noble.

January 28, 2024

QotD: Never depend on “surveys” for real-world issues

There’s a reason “social science” is all horseshit, and that reason is: surveys. All of this stuff is based on surveys, and as it happens, I have quite a bit of experience of being on the receiving end of these. You see, back in grad school I was involved with a young lady in the Soash Department — I know, I know, but a man has certain needs, ya feel me? — and so I was always on call to take whatever goofy little tests they dreamed up, as a favor to her and her equally spastic hardcore Lefty friends. Anecdotes aren’t data, of course, but I’ve got a lot of anecdotes, and I can tell you — anecdotally — that there are two huge, self-reinforcing problems with these surveys: a) respondent pool, and b) design.

The respondent pool is, overwhelmingly, college kids taking them for class credit. Knowing what we know about Basic College Girls, who again are the majority of all college kids, is it any surprise that the results just happen to confirm the conclusions the slightly older, but no less Basic, Grad Student Girls were looking for? Throw in the design problem — questions about as subtle as “Do you think all races should be treated equally, or are you a monster?” — and you’ve got scientific proof that Liberals are good people and Conservatives suck.

Severian, “Is vs. Ought II: Moral Foundations Theory”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-20.

October 18, 2023

QotD: The role of violence in historical societies

Reading almost any social history of actual historical societies reveal complex webs of authority, some of which rely on violence and most of which don’t. Trying to reduce all forms of authority in a society to violence or the threat of violence is a “boy’s sociology”, unfit for serious adults.

This is true even in historical societies that glorified war! Taking, for instance, medieval mounted warrior-aristocrats (read: knights), we find a far more complex set of values and social bonds. Military excellence was a key value among the medieval knightly aristocracy, but so was Christian religious belief and observance, so were expectations about courtly conduct, and so were bonds between family and oath-bound aristocrats. In short there were many forms of authority beyond violence even among military aristocrats. Consequently individuals could be – and often were! – lionized for exceptional success in these other domains, often even when their military performance was at best lackluster.

Roman political speech, meanwhile, is full of words to express authority without violence. Most obviously is the word auctoritas, from which we get authority. J.E. Lendon (in Empire of Honor: The Art of Government in the Roman World (1997)), expresses the complex interaction whereby the past performance of virtus (“strength, worth, bravery, excellence, skill, capacity”, which might be military, but it might also be virtus demonstrated in civilian fields like speaking, writing, court-room excellence, etc) produced honor which in turn invested an individual with dignitas (“worth, merit”), a legitimate claim to certain forms of deferential behavior from others (including peers; two individuals both with dignitas might owe mutual deference to each other). Such an individual, when acting or especially speaking was said to have gravitas (“weight”), an effort by the Romans to describe the feeling of emotional pressure that the dignitas of such a person demanded; a person speaking who had dignitas must be listened to seriously and respected, even if disagreed with in the end. An individual with tremendous honor might be described as having a super-charged dignitas such that not merely was some polite but serious deference, but active compliance, such was the force of their considerable honor; this was called auctoritas. As documented by Carlin Barton (in Roman Honor: Fire in the Bones (2001)), the Romans felt these weights keenly and have a robust language describing the emotional impact such feelings had.

Note that there is no necessary violence here. These things cannot be enforced through violence, they are emotional responses that the Romans report having (because their culture has conditioned them to have them) in the presence of individuals with dignitas. And such dignitas might also not be connected to violence. Cicero clearly at points in his career commanded such deference and he was at best an indifferent soldier. Instead, it was his excellence in speaking and his clear service to the Republic that commanded such respect. Other individuals might command particular auctoritas because of their role as priests, their reputation for piety or wisdom, or their history of service to the community. And of course beyond that were bonds of family, religion, social group, and so on.

And these are, to be clear, two societies run by military aristocrats as described by those same military aristocrats. If anyone was likely to represent these societies as being entirely about the commission of violence, it would be these fellows. And they simply don’t.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part III: The Cult of the Badass”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

September 15, 2023

QotD: Modernism into Post-Modernism

The beasts of modernism have mutated into the beasts of postmodernism — relativism into nihilism, amorality into immorality, irrationality into insanity, sexual deviancy into polymorphous perversity. And since then, generations of intelligent students under the guidance of their enlightened professors have looked into the abyss, have contemplated those beasts, and have said, “How interesting, how exciting.”

Gertrude Himmelfarb, On Looking into the Abyss, 1994.

August 9, 2023

“Soon, they say, white America will be over”

At Oxford Sour, Christopher Gage considers the prominent media narrative about the inevitability of a “majority-minority” America within the next twenty years:

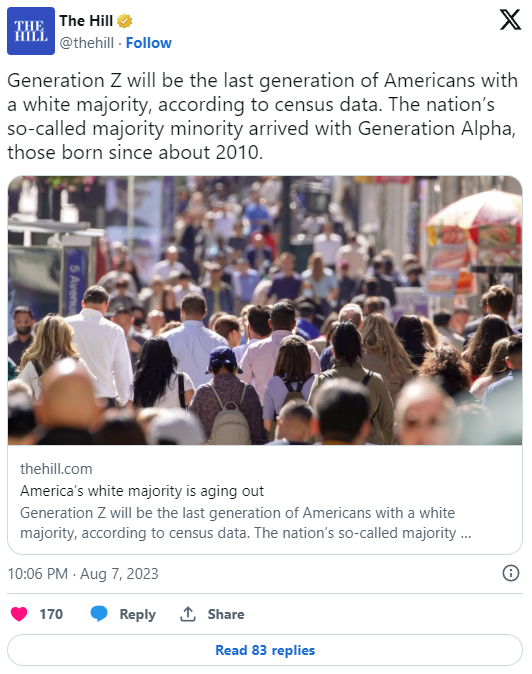

According to both the Daily Stormer and the Washington Post‘s Jennifer Rubin, white people will be a minority sometime in the 2040s.

In 2008, the U.S. Census Bureau projected that “non-Hispanic” white Americans would fall to 49 percent by the year 2042.

Since then, breathless media-politicos have taken the coming “majority-minority” as gospel. Some on the left celebrate the forthcoming date as the first day of their permanent dominance. Some on the right employ the doomsday date to encourage lunatics to rub out innocent people in a synagogue.

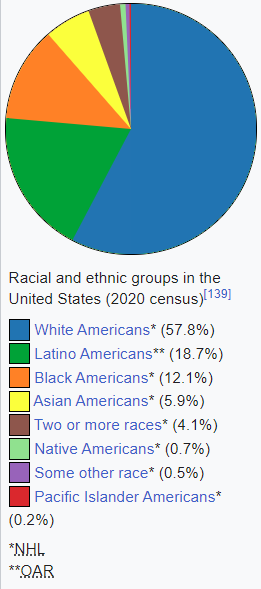

The 2020 census continued the theme. Breathless, lazy journalists took the clickbait. Ominously, they said the white population was “shrinking”. According to the Census Bureau, the white population shrunk to just 57.8 percent. Michael Moore did a little dance.

On white nationalist forums, users with names like WhiteGenocide88 were traumatised, and tooling up for war. No doubt, there are a few Robert Bowers with monstrous campaigns lurking around their skulls.

The problem with this theory, or so my Jewish puppet masters instruct me to say, is that it’s nonsense.

Firstly, the white population didn’t “shrink”. Not unless one believes the Jim Crow “one-drop” rule meaning one non-white ancestor renders one non-white. Secondly, the census ignores millions of white Americans who check the “Hispanic” box. These Americans more than cover any white decline.

According to the census, only those of one hundred percent white European ancestry are white. The Ku Klux Klan tends to agree.

For the first time on the census form, white people could include their varied multi-racial ancestry. Over 31 million whites did so. When we count these white people as white, the white population climbs to 71 percent. So, rather than “shrinking”, the white population has since 2010 increased by four million.

With a sensible definition of white, even by 2060, America remains around 70 percent white.

Professor Richard Alba, a sociologist at the City University of New York, says that definition means America remains a majority-white nation indefinitely — no doomsday clock, no murderous rampages, no primitive bloodsport over a faulty horoscope.

I’m no demographer but counting all white people as white people means there are more white people. I’m no sociologist either but revealing the increase in white people means fewer Robert Bowers keen to pump shotgun rounds into human flesh.

At Not the Bee, Joel Abbott is concerned about the obvious glee displayed by legacy media folks when they push the “replacement” story line:

You can practically feel the excitement here from the quivering fingers of the journalist that wrote this.

Ah.

Hmm.

Well, this is awkward.

See, I’m told this isn’t happening. White people aren’t being “replaced,” they’re just simply being phased out with a percentage that isn’t white at the same time all our institutions, companies, and leaders are pushing to eradicate things like “whiteness” and “white rage” in the name of equity.

For the record, I really couldn’t care less about the skin color of who lives in America. I care an infinite amount more about the spiritual worldview and values of my neighbor than whether their physical DNA gave them dark skin, blue eyes, or a big nose.

This is why I find it weird that the media keeps reporting, with abject glee, that people who look like me will be in the minority soon.

July 19, 2023

Ever wonder where the term “two-spirit” came from?

In Spiked, Malcolm Clark explains the origin of the now commonly used term as a portmanteau for many different words — with significant variation in meaning — in indiginous languages:

The term two-spirit was first formally endorsed at a conference of Native American gay activists in 1990 in Winnipeg in Canada. It is a catch-all term to cover over 150 different words used by the various Indian tribes to describe what we think of today as gay, trans or various forms of gender-bending, such as cross-dressing. Two-spirit people, the conference declared, combine the masculine and the feminine spirits in one.

From the start, the whole exercise reeked of mystical hooey. Myra Laramee, the woman who proposed the term in 1990, said it had been given to her by ancestor spirits who appeared to her in a dream. The spirits, she said, had both male and female faces.

Incredibly, three decades on, there are now celebrities and politicians who endorse the concept or even identify as two-spirit. The term has found its way into one of Joe Biden’s presidential proclamations and is a constant feature of Canadian premier Justin Trudeau’s doe-eyed bleating about “2SLGBTQQIA+ rights”.

The term’s success is no doubt due in part to white guilt. There is a tendency to associate anything Native American with a lost wisdom that is beyond whitey’s comprehension. Ever since Marlon Brando sent “Apache” activist Sacheen Littlefeather to collect his Oscar in 1973, nothing has signalled ethical superiority as much as someone wearing a feather headdress.

The problem is that too many will believe almost any old guff they are told about Native Americans. This is an open invitation to fakery. Ms Littlefeather, for example, may have built a career as a symbol of Native American womanhood. But after her death last year, she was exposed as a member of one of the fastest growing tribes in North America: the Pretendians. Her real name was Marie Louise Cruz. She was born to a white mother and a Mexican father, and her supposed Indian heritage had just been made up.

Much of the fashionable two-spirit shtick is just as fake. For one thing, it’s presented as an acknowledgment of the respect Indian tribes allegedly showed individuals who were gender non-conforming. Yet many of the words that two-spirit effectively replaces are derogatory terms.

In truth, there was a startling range of attitudes to the “two-spirited” among the more than 500 separate indigenous Native American tribes. Certain tribes may have been relaxed about, say, effeminate men. Others were not. In his history of homosexuality, The Construction of Homosexuality (1998), David Greenberg points out that those who are now being called “two spirit” were ridiculed by the Papago, held in contempt by the Choctaws, disliked by the Cocopa, treated by the Seven Nations with “the most sovereign contempt” and “derided” by the Sioux. In the case of the Yuma, who lived in what is now Colorado, the two-spirited were sometimes treated as rape objects for the young men of the tribe.

May 31, 2023

Alvin Toffler may have been utterly wrong in Future Shock, but I suspect his huge royalty cheques helped soften the pain

Ted Gioia on the huge bestseller by Alvin Toffler that got its predictions backwards:

Back in 1970, Alvin Toffler predicted the future. It was a disturbing forecast, and everybody paid attention.

People saw his book Future Shock everywhere. I was just a freshman in high school, but even I bought a copy (the purple version). And clearly I wasn’t alone — Clark Drugstore in my hometown had them piled high in the front of the store.

The book sold at least six million copies and maybe a lot more (Toffler’s website claims 15 million). It was reviewed, translated, and discussed endlessly. Future Shock turned Toffler — previously a freelance writer with an English degree from NYU — into a tech guru applauded by a devoted global audience.

Toffler showed up on the couch next to Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. Other talk show hosts (Dick Cavett, Mike Douglas, etc.) invited him to their couches too. CBS featured Toffler alongside Arthur C. Clarke and Buckminster Fuller as trusted guides to the future. Playboy magazine gave him a thousand dollar award just for being so smart.

Toffler parlayed this pop culture stardom into a wide range of follow-up projects and businesses, from consulting to professorships. When he died in 2016, at age 87, obituaries praised Alvin Toffler as “the most influential futurist of the 20th century”.

But did he deserve this notoriety and praise?

Future Shock is a 500 page book, but the premise is simple: Things are changing too damn fast.

Toffler opens an early chapter by telling the story of Ricky Gallant, a youngster in Eastern Canada who died of old age at just eleven. He was only a kid, but already suffered from “senility, hardened arteries, baldness, slack, and wrinkled skin. In effect, Ricky was an old man when he died.”

Toffler didn’t actually say that this was going to happen to all of us. But I’m sure more than a few readers of Future Shock ran to the mirror, trying to assess the tech-driven damage in their own faces.

“The future invades our lives”, he claims on page one. Our bodies and minds can’t cope with this. Future shock is a “real sickness”, he insists. “It is the disease of change.”

As if to prove this, Toffler’s publisher released the paperback edition of Future Shock with six different covers — each one a different color. The concept was brilliant. Not only did Future Shock say that things were constantly changing, but every time you saw somebody reading it, the book itself had changed.

Of course, if you really believed Future Shock was a disease, why would you aggravate it with a stunt like this? But nobody asked questions like that. Maybe they were too busy looking in the mirror for “baldness, slack, and wrinkled skin”.

Toffler worried about all kinds of change, but technological change was the main focus of his musings. When the New York Times reviewed his book, it announced in the opening sentence that “Technology is both hero and villain of Future Shock“.

During his brief stint at Fortune magazine, Toffler often wrote about tech, and warned about “information overload”. The implication was that human beings are a kind of data storage medium — and they’re running out of disk space.

April 5, 2023

Justin Trudeau chooses the Argentinian model over the Canadian model

In The Line, Matt Gurney considers the proposition that “Canada is broken”:

To the growing list of articles grappling with the issue of whether Canada is broken — and how it’s broken, if it is — we can add this one, by the Globe and Mail‘s Tony Keller. I can say with all sincerity that Keller’s is one of the better, more thoughtful examples in this expanding ouevre. Keller takes the issue seriously, which is more than can be said of some Canadian thought leaders, whose response to the question is often akin to the Bruce Ismay character from Titanic after being told the ship is doomed.

(Spoiler: it sank.)

But back to the Globe article. Specifically, Keller writes about how once upon a time, just over a century ago, Canada and Argentina seemed to be on about the same trajectory toward prosperity and stability. If anything, Argentina may have had the edge. Those with much grasp of 20th-century history will recall that that isn’t exactly how things panned out. I hope readers will indulge me a long quote from Keller’s piece, which summarizes the key points:

By the last third of the 20th century, [Argentina] had performed a rare feat: it had gone backward, from one of the most developed countries to what the International Monetary Fund now classifies as a developing country. Argentina’s economic output is today far below Canada’s, and consequently the average Argentinian’s income is far below that of the average Canadian.

Argentina was not flattened by a meteor or depopulated by a plague. It was not ground into rubble by warring armies. What happened to Argentina were bad choices, bad policies and bad government.

It made no difference that these were often politically popular. If anything, it made things worse since the bad decisions – from protectionism to resources wasted on misguided industrial policies to meddling in markets to control prices – were all the more difficult to unwind. Over time the mistakes added up, or rather subtracted down. It was like compound interest in reverse.

And this, Keller warns, might be Canada’s future. As for the claim made by Pierre Poilievre that “Canada is broken”, Keller says this: “It’s not quite right, but it isn’t entirely wrong.”

I disagree with Keller on that, but I suspect that’s because we define “broken” differently. We at The Line have tried to make this point before, and it’s worth repeating here: we think a lot of the pushback against the suggestion that Canada might be broken is because Canada is still prosperous, comfy, generally safe, and all the rest. Many, old enough to live in paid-off homes that are suddenly worth a fortune, may be enjoying the best years of their lives, at least financially speaking. Suggesting that this is “broken” sometimes seems absurd.

But it’s not: it’s possible we are broken but enjoying a lag period, spared from feeling the full effects of the breakdown by our accumulated wealth and social capital. The engines have stopped, so to speak, but we still have enough momentum to keep sailing for a bit. Put more bluntly, “broken” isn’t a synonym for “destroyed”. A country can still be prosperous and stable and also be broken — especially if it was prosperous and stable for long enough before it broke. The question then becomes how long the prosperity and stability will last. Canada is probably rich enough to get away with being broken for a good long while. What’s already in the pantry will keep us fed and happy for years to come.

But not indefinitely.

November 25, 2022

QotD: Cults, conspiracy theories, progressives, and “the death wish”

The more refined the man — crusty old badthinkers like E.B. Tylor and Lucien Levy-Bruhl would say “civilized”, and of course you shouldn’t look those names up, much less read their works, they are very very bad — the greater his sense of time … and the greater his death wish. In fact, at some point in the “civilization” process, Whitey gets so “over-civilized” that he reverts to what is effectively bicamerality (if Jaynes does it for you) or to the primitive sense of the endless now …

… but alas, he does NOT lose his neuroses, his death wish. That becomes all-consuming.

When the very smart boys in the sociology departments first started studying cults, they assumed — being very smart boys — that cult members would all be dumb, mal-educated yokels. After all, those are the only kind who believe in Magic Sky Fairies, no? But because the urge to suppress or falsify research findings that don’t fit their pre-chosen Narrative hadn’t entirely permeated the academy yet, they actually published their “counterintuitive” findings — the average cult member is smarter, and much better educated, than the hoi polloi.

Which should’ve been obvious by the fact that cults as a general rule don’t bother trying to recruit in slums, or out in the sticks, but DO focus almost their entire recruiting effort near college campuses. They could’ve skipped the fieldwork entirely, and just looked around at the very obvious cult of “Leftism” that they and all their colleagues were already in, but self-awareness has never been a thing on the Left, and that goes triple for the egghead set.

The other thing that becomes immediately obvious in the academic study of cults is that the phrase “suicide cult” is redundant. They’re all suicide cults. Lots of them do us the great favor of admitting it, one way or the other, but THE cult belief is in the imminent immanentizing of the eschaton. The world’s gonna end, and they’re going to be the Big Guy’s right-hand persyns in the new dispensation. The Big Guy could be God, Jesus, the saucer people, Cthulhu, Satan, the Proletariat, whatever — they have a bewildering variety of mythologies, but the underlying belief is exactly the same, every time, and there’s only that ONE belief:

The world is gonna end in their lifetimes, and they themselves are helping to make it happen sooner.

Thus to pscircle back to [the] question: “has there been a historical situation where there is a generalised cult mentality which is attached and detached to a serial cult sequence (coof, ukraine, trump, etc).”

The way I’m interpreting this (please correct me if I’m wrong) is that the Juggalo Cult, unlike all the other known cults throughout history, seems to be able to change its mythology on a dime. We’re all familiar with Festinger, yeah? If not, go read When Prophecy Fails at the nearest opportunity — it’s short, and surprisingly readable for academic sociology. The UFO cult Festinger studied predicted the end of the world. When it didn’t happen, lots of members left the cult … but lots didn’t, and in fact they doubled down — it was only their constant vigilance, they said, that kept the saucer people from destroying the earth as originally planned.

(This is where the phrase “cognitive dissonance” comes from, by the way. Festinger coined it).

Note that the UFO cultists didn’t suddenly flip mythologies as a way to deal with their cogdis — oh, we were wrong, it wasn’t the saucer people, it was the Illuminati. And that seems to apply to any “disconfirmation” of any cult belief. Everything that happens, or doesn’t happen, gets folded in. In the same way, there’s only ever one Devil. See e.g. every conspiracy theory on the Internet, ever. When ___ happens, the guys who think the Freemasons control the world blame the Freemasons, the guys who think it’s the saucer people blame it on the saucer people, etc., same as it ever was.

But if the Freemasons step up and take credit for it, the guys who think it’s the saucer people don’t shrug and say ooops. Rather, they build it in — ok, ok, yeah, technically it was the Freemasons, but we all know who really controls the Freemasons! (It’s the saucer people and the RAND Corporation, in conjunction with the reverse vampires. We’re through the looking glass here, people).

In a sense, of course, the Juggalo Cult does do that — Whitey is always the Devil (do a find-and-replace, swapping in “White supremacy” for “capitalism”, and you could republish the entire Collected Works of V.I. Lenin, verbatim, as your dissertation and no one would be the wiser). But the Juggalos also seem to be unique in that the Apocalypse changes on a dime, too. Festinger’s cult all agreed that the saucer people were still going to destroy the world; they just hadn’t gotten around to it yet, because reasons.

The Juggalo Cult, by contrast, lurches from apocalypse to apocalypse. Global Cooling! Global Warming! Global Climate Change! Reagan! Boooosh! Drumpf! Covid! Ukraine! The Supreme Court! THE CURRENT THING!!!!

This, I think, is the reversion to bicamerality — the “digital clock effect” […] The Juggalo Cultists are still oppressed by their two-millennia-old sense of the passage of linear time — it’s baked into their DNA at this point — but they’ve been acculturated to the Endless Now of social media. There is no past on Twitter, nor any future — there’s just retweets and upvotes and replies, and what’s at the top of the news feed is all that is or could ever be, world without end amen.

They’re trapped in an endless loop — everything they do immanentizes the eschaton, because immanentizing the eschaton is simply a matter of tweeting it. And yet, the eschaton never comes. The tweet is merely replaced by another tweet, which is the only thing in the universe. It’s like what some old “paranormal researchers” said ghosts are — little loops of “film”, endlessly replaying the same thing forever. Time passes — the haunted house is bought and sold, remodeled, added to, stripped to the bricks and rebuilt, bought and sold again — but the ghost is still there, endlessly replaying the same scene, because it’s just static, just energy discharge from some kind of psychic dry-cell battery.

The difference being, of course, that these ghosts can actually pull the nuclear trigger … and they won’t even know they’re doing it, in the same way that the ghosts don’t realize they’re scaring the “occupants” of the “haunted house”, because there ARE no occupants, no house. It’s just the flickering, endlessly repeating NOW.

Severian, “The Ghosts”, Founding Questions, 2022-05-17.

May 3, 2022

England’s class system, as documented by George Orwell and Theodore Dalrymple

I occasionally run into articles online that are clearly written to interest someone like me, and this one in Quillette by Laurie Wastell had my full attention from the title onward:

Ever since Marx, the concept of class has been foundational to sociology — as well as to almost everything else. This would not have surprised the German economist, for class, as he saw it, determines all: one’s motivations, one’s social position, even one’s consciousness. Britain, where Marx’s Capital was written, has long been known for its intricate class system, and as such is the source of much writing on the subject. Two of the most acerbic English social critics of the past century, George Orwell and Theodore Dalrymple, take class as a central subject. Drawing on firsthand experience (Orwell as a journalist, Dalrymple as a prison doctor and psychiatrist), both document in detail the suffering and privations of the class below them. Both also contend that a central cause of this poverty is the indifference of the middle and upper classes, a conclusion Marx would surely have agreed with. Yet, despite this, their work stands in flat contradiction to Marx’s central dogma that the material conditions of a society determine everything about it, including class. In their literary journalism, the authors’ social commentaries and insights into the human condition far surpass Marx’s “scientific” analysis.

[…]

That class is a function more of outlook than income was clear to Orwell, as he explains in his 1937 book The Road to Wigan Pier, which depicts both the privations of working-class life and the British class system as a whole. Orwell describes how the “lower-upper-middle-class” (Orwell’s own), generally professionals in the “Army, Navy, Church, Medicine [or] Law”, understood and aspired to all the many customs of the upper classes (hunting, servants, how to order dinner correctly) despite never being able to afford them. Thus, “To belong to this class when you were [only] at the £400 a year level was a queer business, for it meant that your gentility was almost purely theoretical.” This same dynamic applies today (though the bourgeois values aspired to now are quite different): a poor librarian is far less likely than a wealthy plumber to have voted for causes like Brexit or Trump, which are both populist and, thus, lower-class.

Themselves men of letters, both Orwell and Dalrymple understand that this class distinction is frequently signalled through language. “As for the technical jargon of the Communists,” writes Orwell, “it is as far removed from the common speech as the language of a mathematical textbook.” Such contorted academic prose means little to the ordinary worker, for whom, Orwell argues, Socialism simply means “justice and common decency”. Indeed, Orwell laments that “the worst advertisement for Socialism is its adherents” because of their distance from everyday concerns and inability to speak plainly. Summarising the problem, he quips: “The ordinary man may not flinch from a dictatorship of the proletariat, if you offer it tactfully; offer him a dictatorship of the prigs, and he gets ready to fight”.

A lifelong socialist, Orwell was repeatedly frustrated by the symptoms of this intellectual snobbery — why do the revolutionaries have such disdain for the ordinary punter? Dalrymple, meanwhile, in his essay “How — and How Not — to Love Mankind”, takes aim at its roots. Here, Dalrymple compares the life and work of Marx to his now lesser-known contemporary, Russian novelist and playwright Ivan Turgenev. Though their lives closely resembled one another’s, Dalrymple argues, “They nevertheless came to view human life and suffering in very different, indeed irreconcilable, ways — through different ends of the telescope, as it were. Turgenev saw human beings as individuals always endowed with consciousness, character, feelings, and moral strengths and weaknesses. Marx saw them always as snowflakes in an avalanche, as instances of general forces, as not yet fully human because utterly conditioned by their circumstances.”

[…]

Both writers criticise intellectuals’ pretentious jargon, but it is worth pausing over how each relates his own social position to their subject matter. In a telling passage of Wigan Pier, Orwell describes the working man who has made it into the middle class, perhaps as a Labour MP or trade union official, as “one of the most desolating spectacles the world contains. He has been picked out to fight for his mates, and all it means to him is a soft job and a chance of ‘bettering’ himself. Not merely while but by fighting the bourgeoisie he becomes bourgeois himself.” The scare quotes reflect Orwell’s mixed feelings about social class: does Orwell not believe that a middle-class career — such as his own — is an improvement over the harsh, backbreaking labour of the miners he so vividly documents? He has hit on a deep dilemma, born of a compassionate humanism that points in contradictory directions.

Ostensibly, Orwell chronicles poverty in order to change it, to shock the comfortable hearts of his readers into action. Yet, at the same time, (romanticising the poor against his own advice), he presents the dirt as liberating: squalor and poverty are in some sense more authentic, more real than bourgeois comforts. Thus, as literary critic John Carey argues, Orwell’s “phobia about lower-class dirt collides head-on with his determination to invest dirt with political value, as the price of liberty.”

January 15, 2022

QotD: “Jack Ketch as Eugenist”

Has any historian ever noticed the salubrious effect, on the English character, of the frenzy for hanging that went on in England during the Eighteenth Century? When I say salubrious, of course, I mean in the purely social sense. At the end of the Seventeenth Century the Englishman was still one of the most turbulent and lawless of civilized men; at the beginning of the Ninteenth he was the most law-abiding; i.e., the most docile. What worked the change in him? I believe that it was worked by the rope of Jack Ketch. During the Eighteenth Century the lawless strain was simply choked out of the race. Perhaps a third of those in whose veins it ran were actually hanged; the rest were chased out of the British Isles, never to return. Some fled to Ireland, and revivified the decaying Irish race: in practically all the Irish rebels of the past century there have been plain traces of English blood. Others went to the Dominions. Yet others came to the United States, and after helping to conquer the Western wilderness, begat the yeggman, Prohibition agents, footpads and hijackers of to-day.

The murder rate is very low in England, perhaps the lowest in the world. It is low because nearly all the potential ancestors of murderers were hanged or exiled in the Eighteenth Century. Why is it so high in the United States? Because most of the potential ancestors of murderers, in the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries were not hanged. And why did they escape? For two plain reasons. First, the existing government was too weak to track them down and execute them, especially in the West. Second, the qualities of daring and enterprise that went with their murderousness were so valuable that it was socially profitable to overlook their homicides. In other words the job of occupying and organizing the vast domain of the new Republic was one that demanded the aid of men who, among other things, occasionally butchered their fellow men. The butchering had to be winked at in order to get their help. Thus the murder rate, on the frontier, rose to unprecedented heights, while the execution rate remained very low. Probably 100,000 men altogether were murdered in the territory west of the Ohio between 1776 and 1865; probably not 100 murderers were formally executed. When they were punished at all, it was by other murderers — and this left the strain unimpaired.

H.L. Mencken, “Miscellaneous Notes: Jack Ketch as Eugenist”, Prejudices: Fifth Series, 1926.

August 5, 2021

Sarah Hoyt on “scientific government”

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise (which came out a few days ago, but I’ve been very busy), Sarah Hoyt outlines the genesis of the push for “scientific government” to save us all from ourselves and set right all the ills of the world:

Look, guys, since the middle of the 19th century, the idea of “scientific government” has been running around with pants on its head screaming insults at passerbys.

I like to say we’re still suffering from the consequences of WWI, but things were if not terminal very ill before then. Kings and emperors and Lord knows what else had got the idea of “science” and “permanent progress” stuck in their pin-like heads, which frankly couldn’t retain much more than the correct fork. And there were pet “scientists” and philosophers (the distinction was sometimes arguable. I mean, after all while doing experiments on electricity the 18th century was also fascinated with astral projection and other such things, and made no distinction. And the 19th was not much better.)

By the 20th century with mechanics and the Industrial Revolution paying a dividend in lives saved and prosperity created, these men of “science” were sure that it was only a matter of time till humanity and its reactions, thoughts and governance were similarly under control. And in the twentieth they expected us to become like unto angels.

Now, is there science that saved lives and created the wealthiest society every in the 20th century. DUH. Who the hell is arguing it. Oh, wait, there’s an entire cohort of people denying it. Not so many in the US — I think it’s hard to tell the real thing from foreign idiots posing. But in any case a minuscule contingent — but in France I know there’s a ton of them. They’re running with the bit in their teeth against rationality (I swear to bog) and thought and science. And trying to rebuild the religion of the middle ages. I read them and shake my head.

You see, you have to separate rationality and science from what the government and experts TELL you is rationality and science.

Yes, I know that France built a “Temple to Reason” and you know what? That by itself tells you their revolution was self-copulating and not right in the head. But you don’t need to go that far. Anyone who says they’re “for science” and want equality of results among disparate humans is not reasonable. Or reasoning. Or rational. They are however for sure completely and frackingly insane.

But I do understand the temptation, because so much of what’s being sold as “science” in the schools is not science but the worn out dogmas of people too stupid to know science if it bit them in the fleshy part of the buttocks.

I mean, never mind 2020. Which … you know? Remember how the flu vanished? Turns out the rat bastards were using a test that diagnosed flu as COVID. No, seriously. Malice or stupidity? I don’t know. And neither do you. Probably yes in most cases, though a lot of people have a ton of “learned stupidity”.

Even before 2020 a lot of our ideas on how things worked were lies, particularly those that hinged on or supported the leftist ideas of human kind. Things like Zimbardo’s (Is he dead yet? I need to know when to mark myself safe from being kidnapped by Zimbardo for crazy experiments. No, he really did that.) prisoner experiments; or the rat habitat experiments that supposedly showed that overpopulation had all sorts of bad effects, and therefore we should stop having kids. Turns out those effects are from the loss of social role. Which honestly, anyone who has looked at a conquered country could tell them. Of course, anyone who had looked at mice would also know they’re not humans, but never mind that. […] In fact, practically everything we think we know about psychology or sociology is likely to be a load of crap, if not outright faked.

And history, which is not really a science. Oh. Dear. Lord. Like, you know, the early form of internationalism, with international supply chains and empires caused WWI and … nationalism was blamed for it. Makes perfect sense … in hell.

In fact all this “science” stuff needs to be judged on one thing only: Does it make human lives better/save them? Or is it the astral projection of economics, sociology and psychology? By their fruits, etc.