Fortissax notes some historic parallels between the many, many factions in Spain leading up to the catastrophe of the Spanish Civil War and the many, many factions of the dissident right in the Anglosphere and the rest of the diminishing western world today:

The Spanish Civil War, approximate Nationalist (pink) and Republican (blue) areas of control in September, 1936.

Map by NordNordWest with modifications by “Sting” via Wikimedia Commons.

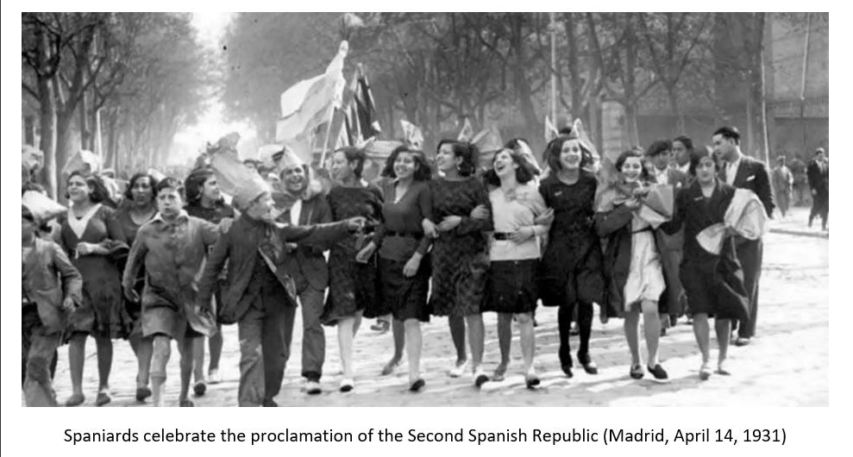

We have serious issues on our hands. We must each contribute through our respective projects and instigate real-world change by pen, sword, or ploughshare. We don’t have time to split, fracture, insult, belittle, destroy each other’s reputations, or engage in character assassination. I liken the factionalism of the (terminally) online right to that of the factions in the Spanish Civil War. The online right is important because the internet is the new “public square”. As influential or more, as mass-action in living, breathing cities. The influence of discourse, media, and content on the internet is insurmountable. While small locally, the impact of each content maker, producer, writer, poet, and videographer is huge. We are part of a civilizational, some would even say global, culture, yet not of it. I will provide examples of some similarities I notice while reading through Peter Kemp’s “Mine Were of Trouble”.

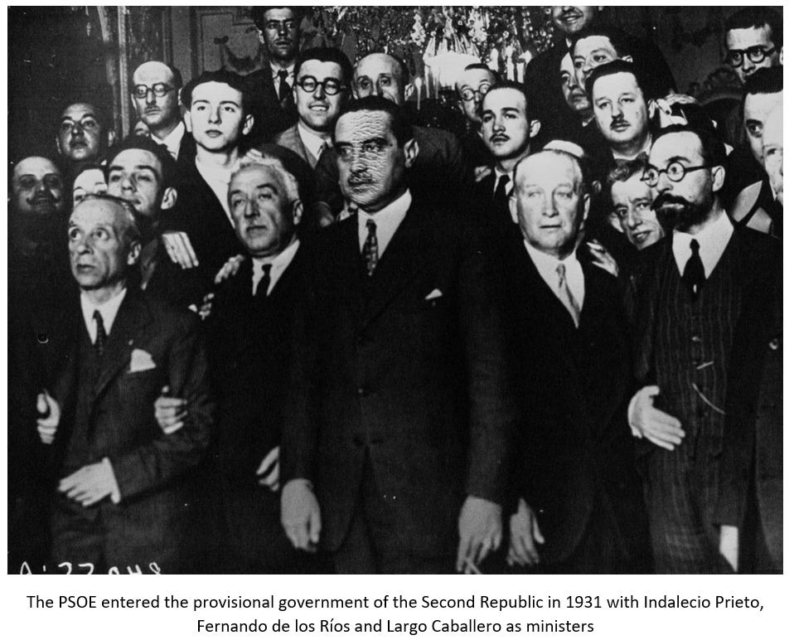

In the buildup to the Spanish Civil War, you had conservative patriots (populists, anti-woke patriot-normies), traditionalist Christian monarchists (who parallel Christ-Is-King people), and the Falangist (who parallel the Vitalists, secular-right). This roughly, parallels the groupings of the Dissident Right today. I believe this is a good case study. History may not repeat itself, but it rhymes. All of them had a lot more in common than they opposed. For example, consider the following points:

- Anti-Communism: Both the Falangists and the Requetés were strongly anti-communist and opposed the Spanish Republic, which they associated with communism, liberalism, and anarchism. They viewed the leftist factions as threats to Spanish traditions, religion, and social order. Today, the Managerial Elite of every single western country has weaponized the New-Left of decades past to use as shock troops against the good people of each nation. We all agree the mass psychosis of capital backed DEI civic cult, their nihilistic, suicidal anti-life acolytes are the most destructive group the human species has ever seen.

- Support for Strong Leaders: Both groups eventually supported General Francisco Franco’s leadership, despite some initial differences in ideology and goals. Franco’s ability to unify the Nationalist forces was crucial to their eventual victory. In many Western countries today, people are rallying behind Trump, Bardella, Farage, Bernier to name a few. They are not perfect, but they are increasingly influenced by Dissident Right ideas, and culture.

- Nationalism: The Falangists and the Requetés were deeply nationalist, believing in the unity and greatness of Spain. They were committed to preserving Spain as a single, undivided nation-state. Today, Dissidents of all stripes support nationalism an civilizational cooperation against outside threats like China, the emerging Republic of India, and the Islamic world, who seek to make excursions in Europe.

- Militarism: Both factions believed in the application of force when necessary to achieve their goals and restore order in Spain. They were heavily involved in the Nationalist military efforts during the civil war. Both the religious right, and the secular Vitalists ostensibly believe a strong body, mind and soul are necessary to enact change. Both hold excellence as a core value, although perhaps one more than the other.

- Benevolent Authoritarianism: Both the Falangists and the Requetés supported authoritarian forms of government. While the Falangists leaned towards a Nietzsche inspired model, the Requetés, rooted in traditional Christian monarchism, were also supportive of strong, centralized authority to maintain order and uphold traditional values.

- Natural Social Order: Both groups believed in a natural social order or organic hierarchy. This concept held that society should be structured according to natural, hierarchical lines, which they saw as inherent and beneficial for maintaining stability and harmony. Do the religious right, and the Vitalists not believe this? That the strong, the beautiful, healthy, are fit to lead? That the most capable should be given the opportunity to advance socially?

- Community Over Individual: While recognizing and respecting the Western man’s innate streak of liberty and individualism, both groups prioritized the needs and values of the community over the individual. They believed that individuals found their true purpose and identity within the larger community and that communal values should guide social and political life. When everyone is doing their part, all prosper.