While Finland, with a tiny population of scarcely 3.5 million, could hardly have threatened the Soviet colossus, it had fought fiercely for independence during the Russian Civil War, conquering Helsinki in April 1918 and dealing the Reds a series of painful blows. The Finnish White Guards — as the Bolsheviks referred to the forces then commanded by the redoubtable Gustaf Mannerheim — had also, Stalin remembered, worked with German troops and collaborated with the British Baltic fleet. Had Mannerheim’s connections with the Germans not been so strong, the British might have lent his Finnish guards more support in the critical days of fall 1919, when Petrograd nearly fell to the Whites. But this was small consolation to Stalin, who mostly remembered the humiliation of losing Finland and Finnish double-dealing with outside powers. The fear that Finland might once again invite in a power hostile to the USSR, whether Britain or Germany, was never far from Stalin’s mind.

When Molotov summoned a Finnish delegation to the Kremlin on October 12th, 1939, Stalin made a personal appearance to heighten the intimidation factor, and he handed the Finns a brutal ultimatum demanding, among other things, “that the frontier between Russia and Finland in the Karelian Isthmus region be moved westward to a point only 20 miles east of Viipuri, and that all existing fortifications on the Karelian Isthmus be destroyed.” Stalin made it clear that this was the price that Finland had to pay to avoid the fate of Poland.

Aggressive and insulting as the Soviet demands on Finland were, Stalin and Molotov fully expected them to be accepted. As the Ukrainian party boss and future general secretary Nikita Khrushchev later recalled, the mood in the Politburo at the time was that “all we had to do was raise our voice a little bit and the Finns would obey. If that didn’t work, we could fire one shot and the Finns would put up their hands and surrender.” Stalin ruled, after all, a heavily armed empire of more than 170 million that had been in a state of near-constant mobilization since early September. The Red Army had already deployed 21,000 modern tanks, while the tiny Finnish Army did not possess an anti-tank gun. The Finnish Air Force had maybe a dozen fighter planes, facing a Red Air armada of 15,000, with 10,362 brand-new warplanes built in 1939 alone. Finnish Army reserves still mostly drilled with wooden rifles dating to the 19th century. By contrast, the Red Army was, in late 1939, the largest in the world, the most mechanized, the most heavily armored, and the most lavishly armed, even if surely not — because of Stalin’s purges — the best led.

[…]

Just past dawn on November 30th, Stalin’s undeclared war against Finland began with a furious artillery barrage on all fronts, followed by the scream of warplanes overhead. The only difference between the bald acts of territorial aggression in Finland and Poland was that the Soviet blitzkrieg was less efficient. Soviet medium bombers — mostly SB-2s cautiously dropping one-ton payloads from heights of 3,000 feet or more — weren’t especially accurate. In Helsinki, Russian bombers failed to knock out a single docking bay, airfield runway, Finnish warplane, or oil tank (although one airport hangar was destroyed). A stray bomb hit the Soviet legation building. According to eyewitnesses, Red fighter pilots strafed Helsinki suburbs as well, “machine-gunning women and children who had fled their houses to the fields.” Similar scenes of horror were repeated in Viipuri (Vyborg), as well as in provincial towns such as Lahti, Enso, and Kotka.

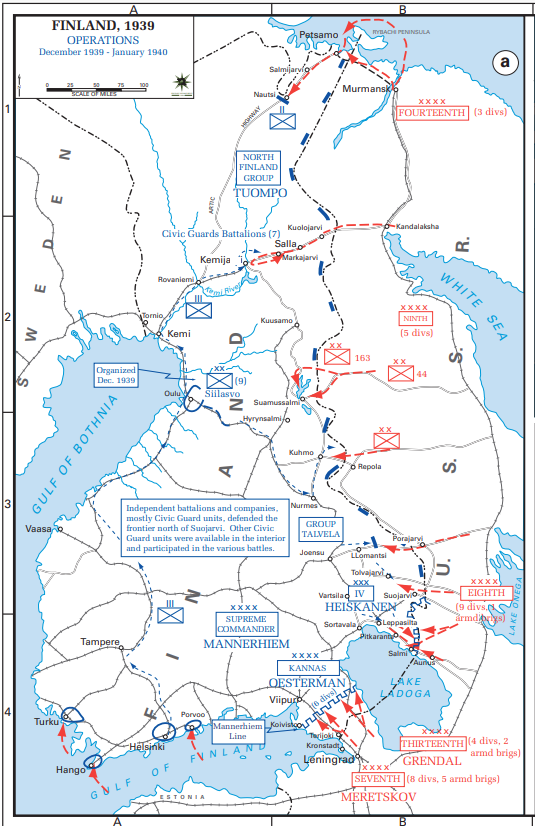

Meretskov’s landward assault on the Karelian Isthmus fared poorly. During the interval between the border incident of November 26th and the Russian onslaught early on November 30th, Mannerheim had wisely evacuated most of the civilian population. A series of clever booby traps were set for the invaders, including “pipe mines” — steel tubes crammed with explosives buried in snowdrifts and set off by hidden trip wires. The most effective defense of all was the Molotov cocktail, first used in Spain but ingeniously updated by the Finns, who would fill liquor bottles with a blend of gasoline or kerosene, tar, and potassium chloride. In fits of derring-do, Finnish soldiers on skis would drop these into the turrets of advancing tanks, ram branches or crowbars into the tank treads, or slice holes in the ice to sink them. Despite boasts in the Russian high command that the campaign would be over in 12 days, by mid-December, most of the Soviet Seventh and Thirteenth Armies were still blundering along short of the Mannerheim Line. On December 17th, in fact, the Thirteenth Army actually went into reverse, retreating after bloody losses in a clash at Taipale. By then, even the tiny Finnish Air Force of old Dutch Fokker fighters had joined the rout, knocking down Soviet bombers — one Finnish ace took out six in four minutes — and doing wonders for the morale of the Finns below. Further north, the Soviet Ninth Army was nearly destroyed in a battle near a burned-out Suomussalmi on December 9th. One Finnish ski sniper, a farmer named Simo Häyhä, personally killed, according to (improbable) legend, more than 500 Russians[*]. Wounded Russians overwhelmed the hospitals of Leningrad. One overworked Soviet surgeon complained in early December that he was dealing with nearly 400 wounded Red Army soldiers every day.

* The story of Simo Häyhä was set to music by Sabaton in their song “White Death” on the Coat of Arms album. Indy Neidell discussed the history behind the music in a Sabaton History video in 2019.

Get 6 months FREE when you sign up for 6 months!

Get 6 months FREE when you sign up for 6 months!  HERE:

HERE:  Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals

Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals