Urging vague and unconstrained government power is not how responsible citizens of a free society ought to act. It’s a bad habit and it’s dangerous and irresponsible to promote it.

This is not an abstract or hypothetical point. We live in a country in which arbitrary power is routinely abused, usually to the detriment of the least powerful and the most abused among us. We live in a country in which we have been panicked into giving the government more and more power to protect us from harm, and that power is most often not used for the things we were told, but to solidify and expand previously existing government power. We live in a country where the government uses the power we’ve already given it as a rationale for giving it more: “how can we not ban x when we’ve already banned y?” We live in a country where vague laws are used arbitrarily and capriciously.

Ken White, “In Support Of A Total Ban on Civilians Owning Firearms”, Popehat, 2016-06-16.

June 27, 2016

QotD: The dangers of expanding the government’s power

March 29, 2016

Why did Apple suddenly grow a pair over consumer privacy and (some) civil rights?

Charles Stross has a theory:

A lot of people are watching the spectacle of Apple vs. the FBI and the Homeland Security Theatre and rubbing their eyes, wondering why Apple (in the person of CEO Tim Cook) is suddenly the knight in shining armour on the side of consumer privacy and civil rights. Apple, after all, is a goliath-sized corporate behemoth with the second largest market cap in US stock market history — what’s in it for them?

As is always the case, to understand why Apple has become so fanatical about customer privacy over the past five years that they’re taking on the US government, you need to follow the money.

[…]

Apple see their long term future as including a global secure payments infrastructure that takes over the role of Visa and Mastercard’s networks — and ultimately of spawning a retail banking subsidiary to provide financial services directly, backed by some of their cash stockpile.

The FBI thought they were asking for a way to unlock a mobile phone, because the FBI is myopically focussed on past criminal investigations, not the future of the technology industry, and the FBI did not understand that they were actually asking for a way to tracelessly unlock and mess with every ATM and credit card on the planet circa 2030 (if not via Apple, then via the other phone OSs, once the festering security fleapit that is Android wakes up and smells the money).

If the FBI get what they want, then the back door will be installed and the next-generation payments infrastructure will be just as prone to fraud as the last-generation card infrastructure, with its card skimmers and identity theft.

And this is why Tim Cook is willing to go to the mattresses with the US department of justice over iOS security: if nobody trusts their iPhone, nobody will be willing to trust the next-generation Apple Bank, and Apple is going to lose their best option for securing their cash pile as it climbs towards the stratosphere.

October 29, 2015

Free HTTPS certificates coming soon

At Ars Technica, Dan Goodin discussed the imminent availability of free HTTPS certificates to all registered domain owners:

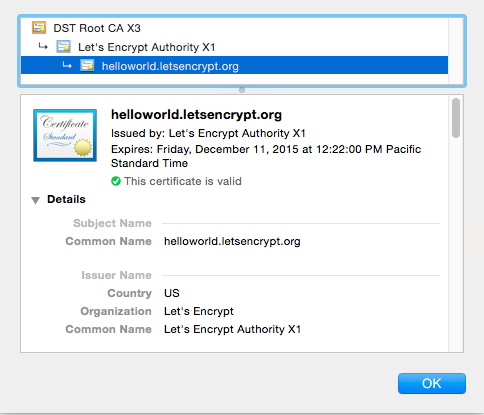

A nonprofit effort aimed at encrypting the entire Web has reached an important milestone: its HTTPS certificates are now trusted by all major browsers.

The service, which is backed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Mozilla, Cisco Systems, and Akamai, is known as Let’s Encrypt. As Ars reported last year, the group will offer free HTTPS certificates to anyone who owns a domain name. Let’s Encrypt promises to provide open source tools that automate processes for both applying for and receiving the credential and configuring a website to use it securely.

HTTPS uses the transport layer security or secure sockets layer protocols to secure websites in two important ways. First, it encrypts communications passing between visitors and the Web server so they can’t be read or modified by anyone who may be monitoring the connection. Second, in the case of bare bones certificates, it cryptographically proves that a server belongs to the same organization or person with control over the domain, rather than an imposter posing as that organization. (Extended validation certificates go a step beyond by authenticating the identity of the organization or individual.)

September 30, 2015

Russia’s “bounty” on TOR

Strategy Page on the less-than-perfect result of Russia’s attempt to get hackers to crack The Onion Router for a medium-sized monetary prize:

Back in mid-2014 Russia offered a prize of $111,000 for whoever could deliver, by August 20th 2014, software that would allow Russian security services to identify people on the Internet using Tor (The Onion Router), a system that enables users to access the Internet anonymously. On August 22nd Russia announced that an unnamed Russian contractor, with a top security clearance, had received the $111,000 prize. No other details were provided at the time. A year later is was revealed that the winner of the Tor prize is now spending even more on lawyers to try and get out of the contract to crack Tor’s security. It seems the winners found that their theoretical solution was too difficult to implement effectively. In part this was because the worldwide community of programmers and software engineers that developed Tor is constantly upgrading it. Cracking Tor security is firing at a moving target and one that constantly changes shape and is quite resistant to damage. Tor is not perfect but it has proved very resistant to attack. A lot of people are trying to crack Tor, which is also used by criminals and Islamic terrorists was well as people trying to avoid government surveillance. This is a matter of life and death in many countries, including Russia.

Similar to anonymizer software, Tor was even more untraceable. Unlike anonymizer software, Tor relies on thousands of people running the Tor software, and acting as nodes for email (and attachments) to be sent through so many Tor nodes that it was believed virtually impossible to track down the identity of the sender. Tor was developed as part of an American government program to create software that people living in dictatorships could use to avoid arrest for saying things on the Internet that their government did not like. Tor also enabled Internet users in dictatorships to communicate safely with the outside world. Tor first appeared in 2002 and has since then defied most attempts to defeat it. The Tor developers were also quick to modify their software when a vulnerability was detected.

But by 2014 it was believed that NSA had cracked TOR and others may have done so as well but were keeping quiet about it so that the Tor support community did not fix whatever aspect of the software that made it vulnerable. At the same time there were alternatives to Tor, as well as supplemental software that were apparently uncracked by anyone.

September 11, 2015

How about creating a truly open web?

Brewster Kahle on the need to blow up change the current web and recreate it with true open characteristics built-in from the start:

Over the last 25 years, millions of people have poured creativity and knowledge into the World Wide Web. New features have been added and dramatic flaws have emerged based on the original simple design. I would like to suggest we could now build a new Web on top of the existing Web that secures what we want most out of an expressive communication tool without giving up its inclusiveness. I believe we can do something quite counter-intuitive: We can lock the Web open.

One of my heroes, Larry Lessig, famously said “Code is Law.” The way we code the web will determine the way we live online. So we need to bake our values into our code. Freedom of expression needs to be baked into our code. Privacy should be baked into our code. Universal access to all knowledge. But right now, those values are not embedded in the Web.

It turns out that the World Wide Web is quite fragile. But it is huge. At the Internet Archive we collect one billion pages a week. We now know that Web pages only last about 100 days on average before they change or disappear. They blink on and off in their servers.

And the Web is massively accessible – unless you live in China. The Chinese government has blocked the Internet Archive, the New York Times, and other sites from its citizens. And other countries block their citizens’ access as well every once in a while. So the Web is not reliably accessible.

And the Web isn’t private. People, corporations, countries can spy on what you are reading. And they do. We now know, thanks to Edward Snowden, that Wikileaks readers were selected for targeting by the National Security Agency and the UK’s equivalent just because those organizations could identify those Web browsers that visited the site and identify the people likely to be using those browsers. In the library world, we know how important it is to protect reader privacy. Rounding people up for the things that they’ve read has a long and dreadful history. So we need a Web that is better than it is now in order to protect reader privacy.

August 28, 2015

The insecurity of the “internet of things” is baked-in right from the start

At The Register, Richard Chirgwin explains why every new “internet of things” release is pretty much certain to be lacking in the security department:

Let me introduce someone I’ll call the Junior VP of Embedded Systems Security, who wears the permanent pucker of chronic disappointment.

The reason he looks so disappointed is that he’s in charge of embedded Internet of Things security for a prominent Smart Home startup.

Everybody said “get into security, you’ll be employable forever on a good income”, so he did.

Because it’s a startup he has to live in the Valley. After his $10k per month take-home, the rent leaves him just enough to live on Soylent plus whatever’s on offer in the company canteen where every week is either vegan week or paleo week.

Nobody told him that as Junior VP for Embedded Systems Security (JVPESS), his job is to give advice that’s routinely ignored or overruled.

Meet the designer

“All we want to do is integrate the experience of the bedside A.M. clock-radio into a fully-social cloud platform to leverage its audience reach and maximise the effectiveness of converting advertising into a positive buying experience”, the Chief Design Officer said (the CDO dresses like Jony Ive, because they retired the Steve Jobs uniform like a football club retiring the Number 10 jumper when Pele quit).

For his implementation, the JVPESS chose a chip so stupid the Republicans want to field it as Trump’s running-mate, wrote a communications spec that did exactly and only what was in the requirements, and briefed the embedded software engineer.

The embedded software engineer only makes stuff actually work, so he earns about one-sixth that of the User Experience Ninja that reports to Jony Ive’s Style Slave and has to live in Detroit. But he’s boring and conscientious and delivers the code.

Eventually, the JVPESS hands over a design to Jony Ive’s Outfit knowing it’ll end in tears.

Two weeks later, Jony Ive’s Style Slave returns to request approval for “just a couple of last minute revisions. We have to press ‘go’ on the project by close-of-business today so if you could just look this over”.

August 7, 2015

Hacking a Tesla Model S

At The Register, John Leyden talks about the recent revelation that the Tesla Model S has known hacking vulnerabilities:

Security researchers have uncovered six fresh vulnerabilities with the Tesla S.

Kevin Mahaffey, CTO of mobile security firm Lookout, and Cloudflare’s principal security researcher Marc Rogers, discovered the flaws after physically examining a vehicle before working with Elon Musk’s firm to resolve security bugs in the electric automobile.

The vulnerabilities allowed the researchers to gain root (administrator) access to the Model S infotainment systems.

With access to these systems, they were able to remotely lock and unlock the car, control the radio and screens, display any content on the screens (changing map displays and the speedometer), open and close the trunk/boot, and turn off the car systems.

When turning off the car systems, Mahaffey and Rogers discovered that, if the car was below five miles per hour (8km/hr) or idling they were able to apply the emergency hand brake, a minor issue in practice.

If the car was going at any speed the technique could be used to cut power to the car while still allowing the driver to safely brake and steer. Consumer’s safety was still preserved even in cases, like the hand-brake issue, where the system ran foul of bugs.

Despite uncovering half a dozen security bugs the two researcher nonetheless came away impressed by Tesla’s infosec policies and procedures as well as its fail-safe engineering approach.

“Tesla takes a software-first approach to its cars, so it’s no surprise that it has key security features in place that minimised and contained the risk of the discovered vulnerabilities,” the researchers explain.

August 2, 2015

Thinking about realistic security in the “internet of things”

The Economist looks at the apparently unstoppable rush to internet-connect everything and why we should worry about security now:

Unfortunately, computer security is about to get trickier. Computers have already spread from people’s desktops into their pockets. Now they are embedding themselves in all sorts of gadgets, from cars and televisions to children’s toys, refrigerators and industrial kit. Cisco, a maker of networking equipment, reckons that there are 15 billion connected devices out there today. By 2020, it thinks, that number could climb to 50 billion. Boosters promise that a world of networked computers and sensors will be a place of unparalleled convenience and efficiency. They call it the “internet of things”.

Computer-security people call it a disaster in the making. They worry that, in their rush to bring cyber-widgets to market, the companies that produce them have not learned the lessons of the early years of the internet. The big computing firms of the 1980s and 1990s treated security as an afterthought. Only once the threats—in the forms of viruses, hacking attacks and so on—became apparent, did Microsoft, Apple and the rest start trying to fix things. But bolting on security after the fact is much harder than building it in from the start.

Of course, governments are desperate to prevent us from hiding our activities from them by way of cryptography or even moderately secure connections, so there’s the risk that any pre-rolled security option offered by a major corporation has already been riddled with convenient holes for government spooks … which makes it even more likely that others can also find and exploit those security holes.

… companies in all industries must heed the lessons that computing firms learned long ago. Writing completely secure code is almost impossible. As a consequence, a culture of openness is the best defence, because it helps spread fixes. When academic researchers contacted a chipmaker working for Volkswagen to tell it that they had found a vulnerability in a remote-car-key system, Volkswagen’s response included a court injunction. Shooting the messenger does not work. Indeed, firms such as Google now offer monetary rewards, or “bug bounties”, to hackers who contact them with details of flaws they have unearthed.

Thirty years ago, computer-makers that failed to take security seriously could claim ignorance as a defence. No longer. The internet of things will bring many benefits. The time to plan for its inevitable flaws is now.

July 17, 2015

The case for encryption – “Encryption should be enabled for everything by default”

Bruce Schneier explains why you should care (a lot) about having your data encrypted:

Encryption protects our data. It protects our data when it’s sitting on our computers and in data centers, and it protects it when it’s being transmitted around the Internet. It protects our conversations, whether video, voice, or text. It protects our privacy. It protects our anonymity. And sometimes, it protects our lives.

This protection is important for everyone. It’s easy to see how encryption protects journalists, human rights defenders, and political activists in authoritarian countries. But encryption protects the rest of us as well. It protects our data from criminals. It protects it from competitors, neighbors, and family members. It protects it from malicious attackers, and it protects it from accidents.

Encryption works best if it’s ubiquitous and automatic. The two forms of encryption you use most often — https URLs on your browser, and the handset-to-tower link for your cell phone calls — work so well because you don’t even know they’re there.

Encryption should be enabled for everything by default, not a feature you turn on only if you’re doing something you consider worth protecting.

This is important. If we only use encryption when we’re working with important data, then encryption signals that data’s importance. If only dissidents use encryption in a country, that country’s authorities have an easy way of identifying them. But if everyone uses it all of the time, encryption ceases to be a signal. No one can distinguish simple chatting from deeply private conversation. The government can’t tell the dissidents from the rest of the population. Every time you use encryption, you’re protecting someone who needs to use it to stay alive.

February 23, 2015

The “Internet of Things” (That May Or May Not Let You Do That)

Cory Doctorow is concerned about some of the possible developments within the “Internet of Things” that should concern us all:

The digital world has been colonized by a dangerous idea: that we can and should solve problems by preventing computer owners from deciding how their computers should behave. I’m not talking about a computer that’s designed to say, “Are you sure?” when you do something unexpected — not even one that asks, “Are you really, really sure?” when you click “OK.” I’m talking about a computer designed to say, “I CAN’T LET YOU DO THAT DAVE” when you tell it to give you root, to let you modify the OS or the filesystem.

Case in point: the cell-phone “kill switch” laws in California and Minneapolis, which require manufacturers to design phones so that carriers or manufacturers can push an over-the-air update that bricks the phone without any user intervention, designed to deter cell-phone thieves. Early data suggests that the law is effective in preventing this kind of crime, but at a high and largely needless (and ill-considered) price.

To understand this price, we need to talk about what “security” is, from the perspective of a mobile device user: it’s a whole basket of risks, including the physical threat of violence from muggers; the financial cost of replacing a lost device; the opportunity cost of setting up a new device; and the threats to your privacy, finances, employment, and physical safety from having your data compromised.

The current kill-switch regime puts a lot of emphasis on the physical risks, and treats risks to your data as unimportant. It’s true that the physical risks associated with phone theft are substantial, but if a catastrophic data compromise doesn’t strike terror into your heart, it’s probably because you haven’t thought hard enough about it — and it’s a sure bet that this risk will only increase in importance over time, as you bind your finances, your access controls (car ignition, house entry), and your personal life more tightly to your mobile devices.

That is to say, phones are only going to get cheaper to replace, while mobile data breaches are only going to get more expensive.

It’s a mistake to design a computer to accept instructions over a public network that its owner can’t see, review, and countermand. When every phone has a back door and can be compromised by hacking, social-engineering, or legal-engineering by a manufacturer or carrier, then your phone’s security is only intact for so long as every customer service rep is bamboozle-proof, every cop is honest, and every carrier’s back end is well designed and fully patched.

February 15, 2015

The term “carjacking” may take on a new meaning

Earlier this month, The Register‘s Iain Thomson summarized the rather disturbing report released by Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) on the self-reported security (or lack thereof) in modern automobile internal networks:

In short, as we’ve long suspected, the computers in today’s cars can be hijacked wirelessly by feeding specially crafted packets of data into their networks. There’s often no need for physical contact; no leaving of evidence lying around after getting your hands dirty.

This means, depending on the circumstances, the software running in your dashboard can be forced to unlock doors, or become infected with malware, and records on where you’ve have been and how fast you were going may be obtained. The lack of encryption in various models means sniffed packets may be readable.

Key systems to start up engines, the electronics connecting up vital things like the steering wheel and brakes, and stuff on the CAN bus, tend to be isolated and secure, we’re told.

The ability for miscreants to access internal systems wirelessly, cause mischief to infotainment and navigation gear, and invade one’s privacy, is irritating, though.

“Drivers have come to rely on these new technologies, but unfortunately the automakers haven’t done their part to protect us from cyber-attacks or privacy invasions,” said Markey, a member of the Senate’s Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee.

“Even as we are more connected than ever in our cars and trucks, our technology systems and data security remain largely unprotected. We need to work with the industry and cyber-security experts to establish clear rules of the road to ensure the safety and privacy of 21st-century American drivers.”

Of the 17 car makers who replied [PDF] to Markey’s letters (Tesla, Aston Martin, and Lamborghini didn’t) all made extensive use of computing in their 2014 models, with some carrying 50 electronic control units (ECUs) running on a series of internal networks.

BMW, Chrysler, Ford, General Motors, Honda, Hyundai, Jaguar Land Rover, Mazda, Mercedes-Benz, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Porsche, Subaru, Toyota, Volkswagen (with Audi), and Volvo responded to the study. According to the senator’s six-page dossier:

- Over 90 per cent of vehicles manufactured in 2014 had a wireless network of some kind — such as Bluetooth to link smartphones to the dashboard or a proprietary standard for technicians to pull out diagnostics.

- Only six automakers have any kind of security software running in their cars — such as firewalls for blocking connections from untrusted devices, or encryption for protecting data in transit around the vehicle.

- Just five secured wireless access points with passwords, encryption or proximity sensors that (in theory) only allow hardware detected within the car to join a given network.

- And only models made by two companies can alert the manufacturers in real time if a malicious software attack is attempted — the others wait until a technician checks at the next servicing.

There wasn’t much detail on the security of over-the-air updates for firmware, nor the use of crypto to protect personal data being phoned home from vehicles to an automaker’s HQ.

January 29, 2015

Mocking “old fashioned” security systems

Christopher Taylor points out that the folks who advised Comcast on their recent home security advertising campaign rather missed the mark:

Comcast is trying to act like using any other security system is old fashioned; its actually a tag line in some of their ads “don’t be old fashioned.” They’re using the old knight in armor to stand in for any other security system which, not being “in the cloud” and accessible “anywhere” from your smart phone is thus dated and old.

But consider; which would be preferable?

- An internet based system which, by its own advertising notes that you can turn it off “from anywhere” using only a phone, and look at cameras anywhere in your home, just by using the phone.

- An armored knight with a broadsword.

Now, perhaps you’re new to the internet and aren’t aware of this, but it gets hacked pretty much every minute of the day. Passwords are stolen and sold on Chinese and Russian websites. Your smart phone is not secure.

I once found a website (now gone) that had live feeds of people’s homes from around the world by clicking on various names. All they did was use commonly used passwords and logged into the security systems. It was like this weird voyeuristic show, but really boring because it was all empty rooms and darkness — people turn on their security when they leave, not when they do fun stuff to watch.What I’m saying is what should be abundantly obvious to everyone who has a television to watch Comcast ads: this is a really stupid, bad idea. You’re making it easier for burglars to turn off your security system and watch for when you aren’t home. You’re making it easier for evil sexual predators and monsters to know your patterns and when you’re home or alone. Get it?

This is like publishing your daily activities and living in a glass building all day long. It seems cool and high tech and new and fancy, but its just really stupid.

But an armored knight? Unless he goes to sleep, he’s a physical, combat-ready soldier that acts as a physical deterrent to intruders.

And its not even old fashioned. It’s so old an image, it doesn’t even feel old fashioned, it feels beyond vintage to a fantasy era. Which is cooler to you, being guarded by a knight in shining armor with a sword, or your smart phone?

These ads have a viral feel to them, like some hip college dude with a fancy business card came up with it for Comcast, but they don’t make sense. I doubt they even get people to want to buy the product.

January 10, 2015

Sub-orbital airliners? Not if you know much about economics and physics

Charles Stross in full “beat up the optimists” mode over a common SF notion about sub-orbital travel for the masses:

Let’s start with a simple normative assumption; that sub-orbital spaceplanes are going to obey the laws of physics. One consequence of this is that the amount of energy it takes to get from A to B via hypersonic airliner is going to exceed the energy input it takes to cover the same distance using a subsonic jet, by quite a margin. Yes, we can save some fuel by travelling above the atmosphere and cutting air resistance, but it’s not a free lunch: you expend energy getting up to altitude and speed, and the fuel burn for going faster rises nonlinearly with speed. Concorde, flying trans-Atlantic at Mach 2.0, burned about the same amount of fuel as a Boeing 747 of similar vintage flying trans-Atlantic at Mach 0.85 … while carrying less than a quarter as many passengers.

Rockets aren’t a magic technology. Neither are hybrid hypersonic air-breathing gadgets like Reaction Engines‘ Sabre engine. It’s going to be a wee bit expensive. But let’s suppose we can get the price down far enough that a seat in a Mach 5 to Mach 10 hypersonic or sub-orbital passenger aircraft is cost-competitive with a high-end first class seat on a subsonic jet. Surely the super-rich will all switch to hypersonic services in a shot, just as they used Concorde to commute between New York and London back before Airbus killed it off by cancelling support after the 30-year operational milestone?

Well, no.

Firstly, this is the post-9/11 age. Obviously security is a consideration for all civil aviation, right? Well, no: business jets are largely exempt, thanks to lobbying by their operators, backed up by their billionaire owners. But those of us who travel by civil airliners open to the general ticket-buying public are all suspects. If something goes wrong with a scheduled service, fighters are scrambled to intercept it, lest some fruitcake tries to fly it into a skyscraper.

So not only are we not going to get our promised flying cars, we’re not going to get fast, cheap, intercontinental travel options. But what about those hyper-rich folks who spend money like water?

First class air travel by civil aviation is a dying niche today. If you are wealthy enough to afford the £15,000-30,000 ticket cost of a first-class-plus intercontinental seat (or, rather, bedroom with en-suite toilet and shower if we’re talking about the very top end), you can also afford to pay for a seat on a business jet instead. A number of companies operate profitably on the basis that they lease seats on bizjets by the hour: you may end up sharing a jet with someone else who’s paying to fly the same route, but the operating principle is that when you call for it a jet will turn up and take you where you want to go, whenever you want. There’s no security theatre, no fuss, and it takes off when you want it to, not when the daily schedule says it has to. It will probably have internet connectivity via satellite—by the time hypersonic competition turns up, this is not a losing bet—and for extra money, the sky is the limit on comfort.

I don’t get to fly first class, but I’ve watched this happen over the past two decades. Business class is holding its own, and premium economy is growing on intercontinental flights (a cut-down version of Business with more leg-room than regular economy), but the number of first class seats you’ll find on an Air France or British Airways 747 is dwindling. The VIPs are leaving the carriers, driven away by the security annoyances and drawn by the convenience of much smaller jets that come when they call.

For rich people, time is the only thing money can’t buy. A HST flying between fixed hubs along pre-timed flight paths under conditions of high security is not convenient. A bizjet that flies at their beck and call is actually speedier across most intercontinental routes, unless the hypersonic route is serviced by multiple daily flights—which isn’t going to happen unless the operating costs are comparable to a subsonic craft.

January 7, 2015

Cory Doctorow on the dangers of legally restricting technologies

In Wired, Cory Doctorow explains why bad legal precedents from more than a decade ago are making us more vulnerable rather than safer:

We live in a world made of computers. Your car is a computer that drives down the freeway at 60 mph with you strapped inside. If you live or work in a modern building, computers regulate its temperature and respiration. And we’re not just putting our bodies inside computers — we’re also putting computers inside our bodies. I recently exchanged words in an airport lounge with a late arrival who wanted to use the sole electrical plug, which I had beat him to, fair and square. “I need to charge my laptop,” I said. “I need to charge my leg,” he said, rolling up his pants to show me his robotic prosthesis. I surrendered the plug.

You and I and everyone who grew up with earbuds? There’s a day in our future when we’ll have hearing aids, and chances are they won’t be retro-hipster beige transistorized analog devices: They’ll be computers in our heads.

And that’s why the current regulatory paradigm for computers, inherited from the 16-year-old stupidity that is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, needs to change. As things stand, the law requires that computing devices be designed to sometimes disobey their owners, so that their owners won’t do something undesirable. To make this work, we also have to criminalize anything that might help owners change their computers to let the machines do that supposedly undesirable thing.

This approach to controlling digital devices was annoying back in, say, 1995, when we got the DVD player that prevented us from skipping ads or playing an out-of-region disc. But it will be intolerable and deadly dangerous when our 3-D printers, self-driving cars, smart houses, and even parts of our bodies are designed with the same restrictions. Because those restrictions would change the fundamental nature of computers. Speaking in my capacity as a dystopian science fiction writer: This scares the hell out of me.

December 17, 2014

The Internet is on Fire | Mikko Hypponen | TEDxBrussels

Published on 6 Dec 2014

This talk was given at a local TEDx event, produced independently of the TED Conferences. The Internet is on Fire

Mikko is a world class cyber criminality expert who has led his team through some of the largest computer virus outbreaks in history. He spoke twice at TEDxBrussels in 2011 and in 2013. Every time his talks move the world and surpass the 1 million viewers. We’ve had a huge amount of requests for Mikko to come back this year. And guess what? He will!

Prepare for what is becoming his ‘yearly’ talk about PRISM and other modern surveillance issues.