seangabb

Published Feb 25, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

• Growth of Tensions between Rival Powers

• Differences of Civilisation

• The Outbreak of War

• The Course of War

• Growth of Roman Sea Power

• The End and Significance of the War

(more…)

February 26, 2024

Rome: Part 4 – The First Punic War 264-241 BC

February 20, 2024

Rome: Part 3 – The Expansion of Roman Power

seangabb

Published Feb 18, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 3: The Expansion of Roman Power

• The Conquest of Central Italy

• The Gallic Sack of 390 BC

• The Conquest of the Greek Cities

• Relations with Carthage

(more…)

February 9, 2024

Rome: Part 2 – Consolidation of the Republic

seangabb

Published Feb 8, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 2: Consolidation of the Republic

• The Roman Revolution against the Kings

• How Brutus put his own sons to death

• How Horatius kept the Bridge

• Scaevola and Lars Porsena

• The Roman Constitution: an Overview

(more…)

His Year: Julius Caesar (59 BC)

Historia Civilis

Published Jul 5, 2016

(more…)

February 3, 2024

A Day in Ancient Rome

toldinstone

Published Nov 10, 2023Following Marcus Aurelius on the day of his final triumph.

Chapters:

0:00 Another day

1:05 Petitions

3:12 Breakfast

3:51 The Triumph

4:44 Romanis Magicae

5:37 Artifacts of the wars

7:09 Caesar, you are mortal

(more…)

February 1, 2024

Rome: Part 1 – Mythical Origins to the Founding of the Republic

seangabb

Published 31 Jan 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 1: Mythical Beginnings and the Founding of Rome (753 BC – 509 BC)

• What is said by the archaeology and modern research on the origins of Rome

• The lack of authentic literary history of Rome in its early period

• Legend of Romulus and Remus

• The establishment of Rome’s early monarchy

• Transition to the Roman Republic

(more…)

December 29, 2023

The Christianization of England

Ed West‘s Christmas Day post recounted the beginnings of organized Christianity in England, thanks to the efforts of Roman missionaries sent by Pope Gregory I:

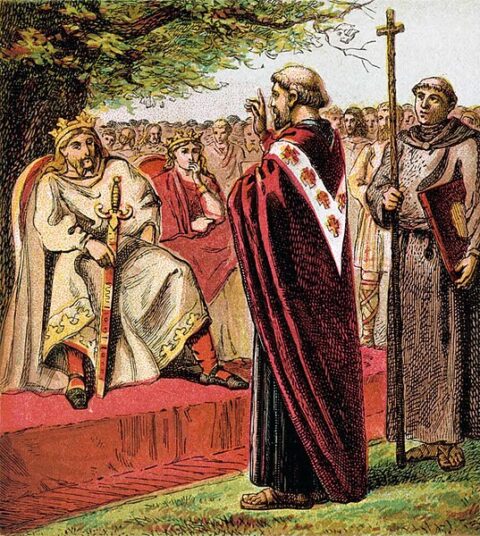

“Saint Augustine and the Saxons”

Illustration by Joseph Martin Kronheim from Pictures of English History, 1868 via Wikimedia Commons.

The story begins in sixth century Rome, once a city of a million people but now shrunk to a desolate town of a few thousand, no longer the capital of a great empire of even enjoying basic plumbing — a few decades earlier its aqueducts had been destroyed in the recent wars between the Goths and Byzantines, a final blow to the great city of antiquity. Under Pope Gregory I, the Church had effectively taken over what was left of the town, establishing it as the western headquarters of Christianity.

Rome was just one of five major Christian centres. Constantinople, the capital of the surviving eastern Roman Empire, was by this point far larger, and also claimed leadership of the Christian world — eventually the two would split in the Great Schism, but this was many centuries away. The other three great Christian centres — Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch — would soon fall to Islam, a turn of events that would strengthen Rome’s spiritual position. And it was this Roman version of Christianity which came to shape the Anglo-Saxon world.

Gregory was a great reformer who is viewed by some historians as a sort of bridge between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the founder of a new and reborn Rome, now a spiritual rather than a military empire. He is also the subject of the one great stories of early English history.

One day during the 570s, several years before he became pontiff, Gregory was walking around the marketplace when he spotted a pair of blond-haired pagan slave boys for sale. Thinking it tragic that such innocent-looking children should be ignorant of the Lord, he asked a trader where they came from, and was told they were “Anglii”, Angles. Gregory, who was fond of a pun, replied “Non Angli, sed Angeli” (not Angles, but angels), a bit of wordplay that still works fourteen centuries later. Not content with this, he asked what region they came from and was told “Deira” (today’s Yorkshire). “No,” he said, warming to the theme and presumably laughing to himself, “de ira” — they are blessed.

Impressed with his own punning, Gregory decided that the Angles and Saxons should be shown the true way. A further embellishment has the Pope punning on the name of the king of Deira, Elle, by saying he’d sing “hallelujah” if they were converted, but it seems dubious; in fact, the Anglo-Saxons were very fond of wordplay, which features a great deal in their surviving literature and without spoiling the story, we probably need to be slightly sceptical about whether Gregory actually said any of this.

The Pope ordered an abbot called Augustine to go to Kent to convert the heathens. We can only imagine how Augustine, having enjoyed a relatively nice life at a Benedictine monastery in Rome, must have felt about his new posting to some cold, faraway island, and he initially gave up halfway through his trip, leaving his entourage in southern Gaul while he went back to Rome to beg Gregory to call the thing off.

Yet he continued, and the island must have seemed like an unimaginably grim posting for the priest. Still, in the misery-ridden squalor that was sixth-century Britain, Kent was perhaps as good as it gets, in large part due to its links to the continent.

Gaul had been overrun by the Franks in the fifth century, but had essentially maintained Roman institutions and culture; the Frankish king Clovis had converted to Catholicism a century before, following relentless pressure from his wife, and then as now people in Britain tended to ape the fashions of those across the water.

The barbarians of Britain were grouped into tribes led by chieftains, the word for their warlords, cyning, eventually evolving into its modern usage of “king”. There were initially at least twelve small kingdoms, and various smaller tribal groupings, although by Augustine’s time a series of hostile takeovers had reduced this to eight — Kent, Sussex, Essex, and Wessex (the West Country and Thames Valley), East Anglia, Mercia (the Midlands), Bernicia (the far North), and Deira (Yorkshire).

In 597, when the Italian delegation finally finished their long trip, Kent was ruled by King Ethelbert, supposedly a great-grandson of the semi-mythical Hengest. The king of Kent was married to a strong-willed Frankish princess called Bertha, and luckily for Augustine, Bertha was a Christian. She had only agreed to marry Ethelbert on condition that she was allowed to practise her religion, and to keep her own personal bishop.

Bertha persuaded her husband to talk to the missionary, but the king was perhaps paranoid that the Italian would try to bamboozle him with witchcraft, only agreeing to meet him under an oak tree, which to the early English had magical properties that could overpower the foreigner’s sorcery. (Oak trees had a strong association with religion and mysticism throughout Europe, being seen as the king of the trees and associated with Woden, Zeus, Jupiter, and all the other alpha male gods.)

Eventually, and persuaded by his wife, Ethelbert allowed Augustine to baptise 10,000 Kentish men on Christmas Day, 597, according to the chronicles. This is probably a wild exaggeration; 10,000 is often used as a figure in medieval history, and usually just means “quite a lot of people”.

December 15, 2023

The Pagan Necropolis Under Vatican City

toldinstone

Published 1 Sept 2023Beneath the floor of St. Peter’s Basilica, an ancient Roman cemetery holds the secret to the origins of Vatican City.

(more…)

December 11, 2023

Roman glossary

As I continue to post QotD entries drawn from Bret Devereaux’s fascinating historical blog A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry (with Dr. Devereaux’s kind permission, I hasten to add), the number of specialized terms from the Roman Republic and Empire also expands. As some of these terms pop up in my shorter excerpts without immediate context, I think that a glossary for Rome is called for (similar to the Spartan glossary, as there’s a lot more Roman content coming up, it being Dr. Devereaux’s area of academic specialization) to help explain the terms that I think may need expansion in these excerpts from his longer posts. As usual, most of the information is drawn directly from ACOUP (often from more than one original post) and where I’ve felt the need to interpolate any additional information it will be enclosed in square brackets. Errors and misinterpretations of his original work are purely mine.

December 10, 2023

QotD: Roman citizenship

As with other ancient self-governing citizen bodies, the populus Romanus (the Roman people – an idea that was defined by citizenship) restricted political participation to adult citizen males (actual office holding was further restricted to adult citizen males with military experience, Plb. 6.19.1-3). And we should note at the outset that citizenship was stratified both by legal status and also by wealth; the Roman Republic openly and actively counted the votes of the wealthy more heavily than those of the poor, for instance. So let us avoid the misimpression that Rome was an egalitarian society; it was not.

The most common way to become a Roman citizen was by birth, though the Roman law on this question is more complex and centers on the Roman legal concept of conubium – the right to marry and produce legally recognized heirs under Roman law. Conubium wasn’t a right held by an individual, but a status between two individuals (though Roman citizens could always marry other Roman citizens). In the event that a marriage was lawfully contracted, the children followed the legal status of their father; if no lawfully contracted marriage existed, the child followed the status of their mother (with some quirks; Ulpian, Reg. 5.2; Gaius, Inst. 1.56-7 – on the quirks and applicability in the Republic and conubium in general, see S.T. Roselaar, “The Concept of Conubium in the Roman Republic” in New Frontiers: Law and Society in the Roman World, ed. P.J. du Plessis (2013)).

Consequently the children of a Roman citizen male in a legal marriage would be Roman citizens and the children of a Roman citizen female out of wedlock would (in most cases; again, there are some quirks) be Roman citizens. Since the most common way for the parentage of a child to be certain is for the child to be born in a legal marriage and the vast majority of legal marriages are going to involve a citizen male husband, the practical result of that system is something very close to, but not quite exactly the same as, a “one parent” rule (in contrast to Athens’ two-parent rule). Notably, the bastard children of Roman women inherited their mother’s citizenship (though in some cases, it would be necessarily, legally, to conceal the status of the father for this to happen, see Roselaar, op. cit., and also B. Rawson, “Spruii and the Roman View of Illegitimacy” in Antichthon 23 (1989)), where in Athens, such a child would have been born a nothos and thus a metic – resident non-citizen foreigner.

The Romans might extend the right of conubium with Roman citizens to friendly non-citizen populations; Roselaar (op. cit.) argues this wasn’t a blanket right, but rather made on a community-by-community basis, but on a fairly large scale – e.g. extended to all of the Campanians in 188 B.C. Importantly, Roman colonial settlements in Italy seem to pretty much have always had this right, making it possible for those families to marry back into the citizen body, even in cases where setting up their own community had caused them to lose all or part of their Roman citizenship (in exchange for citizenship in the new community).

The other long-standing way to become a Roman citizen was to be enslaved by one and then freed. An enslaved person held by a Roman citizen who was then freed (or manumitted) became a libertus (or liberta), by custom immediately the client of their former owner (this would be made into law during the empire) and by law a Roman citizen, although their status as a freed person barred them from public office. Since they were Roman citizens (albeit with some legal disability), their children – assuming a validly contracted marriage – would be full free-born Roman citizens, with no legal disability. And, since freedmen and freedwomen were citizens, they also could contract valid marriages with other Roman citizens, including freeborn ones […]. While most enslaved people in the Roman world had little to no hope of ever being manumitted (enslaved workers, for instance, on large estates far from their owners), Roman economic and social customs functionally required a significant number of freed persons and so a meaningful number of new Roman citizens were always being minted in the background this way. Rome’s apparent liberality with admission into citizenship seems to have been a real curiosity to the Greek world.

These processes thus churned in the background, minting new Romans on the edges of the populus Romanus who subsequently became full members of the Roman community and thus shared fully in the Roman legal identity.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

November 20, 2023

QotD: Flax and linen in the ancient and medieval world

Linen fabrics are produced from the fibers of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. This common flax plant is the domesticated version of the wild Linum bienne, domesticated in the northern part of the fertile crescent no later than 7,000 BC, although wild flax fibers were being used to produce textiles even earlier than that. Consequently the use of linen fibers goes way back. In fact, the oldest known textiles are made from flax, including finds of fibers at Nahal Hemar (7th millennium BC), Çayönü (c. 7000 BC), and Çatalhöyük (c. 6000 BC). Evidence for the cultivation of flax goes back even further, with linseed from Tell Asward in Syria dating to the 8th millennium BC. Flax was being cultivated in Central Europe no later than the second half of the 7th millennium BC.

Flax is a productive little plant that produces two main products: flax seeds, which are used to produce linseed oil, and the bast of the flax plant which is used to make linen. The latter is our focus here so I am not going to go into linseed oil’s uses, but it should be noted that there is an alternative product. That said, my impression is that flax grown for its seeds is generally grown differently (spaced out, rather than packed together) and generally different varieties are used. That said, flax cultivated for one purpose might produce some of the other product (Pliny notes this, NH 19.16-17)

Flax was a cultivated plant (which is to say, it was farmed); fortunately we have discussed quite a bit about farming in general already and so we can really focus in on the peculiarities of the flax plant itself; if you are interested in the activities and social status of farmers, well, we have a post for that. Flax farming by and large seems to have involved mostly the same sorts of farmers as cereal farming; I get no sense in the Greco-Roman agronomists, for instance, that this was done by different folks. Flax farming changed relatively little prior to mechanization; my impression reading on it is that flax was farmed and gathered much the same in 1900 BC as it was in 1900 AD. In terms of soil, flax requires quite a lot of moisture and so grows best in either deep loam or (more commonly used in the ancient world, it seems) alluvial soils; in both cases, it should be loose, unconsolidated “sandy” (that is, small particle-sized) soil. Alluvium is loose, often sandy soil that is the product of erosion (that is to say, it is soil composed of the bits that have been eroded off of larger rocks by the action of water); the most common place to see lots of alluvial soil are in the flood-plains of rivers where it is deposited as the river floods forming what is called an alluvial plain.

Thus Pliny (NH 19.7ff) when listing the best flax-growing regions names places like Tarragona, Spain (with the seasonally flooding Francoli river) or the Po River Basin in Italy (with its large alluvial plain) and of course Egypt (with the regular flooding of the Nile). Pliny notes that linen from Sætabis in Spain was the best in Europe, followed by linens produced in the Po River Valley, though it seems clear that the rider here “made in Europe” in his text is meant to exclude Egypt, which would have otherwise dominated the list – Pliny openly admits that Egyptian flax, while making the least durable kind of linen (see below on harvesting times) was the most valuable (though he also treats Egyptian cotton which, by his time, was being cultivated in limited amounts in the Nile delta, as a form of flax, which obviously it isn’t). Flax is fairly resistant to short bursts of mild freezing temperatures, but prolonged freezes will kill the plants; it seems little accident that most flax production seems to have happened in fairly warm or at least temperate climes.

Flax is (as Pliny notes) a very fast growing plant – indeed, the fastest growing crop he knew of. Modern flax grown for fibers is generally ready for harvesting in roughly 100 days and this accords broadly with what the ancient agronomists suggest; Pliny says that flax is sown in spring and harvested in summer, while the other agronomists, likely reflecting practice further south suggest sowing in late fall and early winter and likewise harvesting relatively quickly. Flax that is going to be harvested for fibers tended to be planted in dense bunches or rows (Columella notes this method but does not endorse it, De Rust. 2.10.17). The reason for this is that when placed close together, the plants compete for sunlight by growing taller and thinner and with fewer flowers, which maximizes the amount of stalk per plant. By contrast, flax planted for linseed oil is more spaced out to maximize the number of flowers (and thus the amount of seed) per plant.

Once the flax was considered ready for harvest, it was pulled up out of the ground (including the root system) in bunches in handfuls rather than as individual plants […] and then hung to dry. Both Pliny and Columella (De Rust. 2.10.17) note that this pulling method tended to tear up the soil and regarded this as very damaging; they are on to something, since none of the flax plant is left to be plowed under, flax cultivation does seem to be fairly tough on the soil (for this reason Columella advises only growing flax in regions with ideal soil for it and where it brings a good profit). The exact time of harvest varies based on the use intended for the flax fibers; harvesting the flax later results in stronger, but rougher, fibers. Late-pulled flax is called “yellow” flax (for the same reason that blond hair is called “flaxen” – it’s yellow!) and was used for more work-a-day fabrics and ropes.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

November 12, 2023

QotD: Archaeological evidence on the foundation of Rome

The first thing we need to talk about is the physical location of Rome and the peoples directly around it. […] Rome in its earliest history was, essentially, a frontier city, placed at the very northern end of Latium, the region of Italy that was populated by Latin-speakers. Rome’s position on the Tiber River put it at the cultural meeting place of the Etruscan (and Faliscian) cultural zone to the North, Latium to the South and Umbrian-speaking peoples in the Apennine uplands to the North-East. To the West, of course, lay the Sea, which by Rome’s legendary founding date was already beginning to fill with seaborne merchants, particularly Phoenician and Greek ones […] These patterns of settlements and cultural zones are both attested in our literary sources but also show up fairly clearly in the archaeology of the region.

Rome itself, a cluster of hills situated at an important ford over the Tiber (and thus a natural trade and migration route running north-south along Italy’s Western side), was already inhabited by the close of the Neolithic with small settlement clusters on several of its hills. As you might well imagine, excavating pre-historic Rome is difficult, due to the centuries of development piled on top of it and the fact that in many cases pre-historic evidence must exist directly below subsequent ruins which are now cultural heritage sites. Nevertheless, archaeology sheds quite a lot of light. That archaeological evidence allows us to reject the sort of “empty fields” city foundation that Livy implies. Rather than being “founded”, the city of Rome as we know it formed out of the political merger of these communities (the technical term is synoecism from Greek συνοικισμóς, literally “[putting] the houses together”). There is, importantly, no clear evidence of any archaeological discontinuity between the old settlements on the hills and the newly forming city; these seem to have been the same people. The Palatine hill, which is “chosen” by Romulus in the legend and would be the site of the houses of Rome’s most important and affluent citizens during the historical period, seems to have been the most prominent of these settlements even at this early stage.

A key event in this merging comes in the mid-600s, when these hill-communities begin draining the small valley that lay between the Capitoline and Palatine hills; this valley would naturally have been marshy and quite useless but once drained, it formed a vital meeting place at the center of these hill communities – what would become the Forum Romanum. That public works project – credited by the Romans to the semi-legendary king Tarquinius Priscus (Plin. Natural History 36.104ff) – is remarkably telling, both because it signals that there was enough of a political authority in Rome to marshal the resources to see it done (suggesting somewhat more centralized government, perhaps early kings) and because the new forum formed the meeting place and political center for these communities, quite literally binding them together into a single polity. It is at this point that we can really begin speaking of Rome and Romans with confidence.

What does our archaeology tell us about this early community at this point and for the next several centuries?

The clearest element of this early polity is the Latin influence. Linguistically, Rome was of Latium, spoke (and wrote their earliest inscriptions) in Latin and it falls quite easily to reason that the majority of the people in these early hilltop communities around the Tiber ford were culturally and linguistically Latins. But there are also strong signs of Etruscan and Greek influence in the temples. For instance, in the Forum Boarium (between the Tiber and the Palatine), we see evidence for a cult location dating to the seventh century, with a temple constructed there in the early sixth century (and reconstructed again towards the end of that century); votive offerings recovered from the site include Attic ware pottery and a votive ivory figurine of a lion bearing an inscription in Etruscan.

Archaeological evidence for the Sabines is less evident. Distinctive Sabine material culture hasn’t been recovered from Rome as of yet. There are some clear examples of linguistic influence from Sabine to Latin, although the Romans often misidentify them; the name of the Quirinal hill, for instance (thought by the Romans to be where the Sabines settled after joining the city) doesn’t seem to be Sabine in origin. That said, religious institutions associated with the hill in the historical period (particularly the priests known as the Salii Collini) may have some Sabine connections. More notably, a number of key Roman families (gentes in Latin; we might translate this word as “clans”) claimed Sabine descent. Of particular note, several of these are Patrician gentes, meaning that they traced their lineage to families prominent under the kings or very early in the Republic. Among these were the Claudii (a key family in Roman politics from the founding of the Republic to the early Empire; Liv. 2.16), the Tarpeii (recorded as holding a number of consulships in the fifth century), and the Valerii (prominent from the early days of the Republic and well into the empire; Dionysius 2.46.3). There seems little reason to doubt the ethnic origins of these families.

So on the one hand we cannot say with certainty that there were Sabines in Rome in the eighth century as Livy would have it (though nothing rules it out), but there very clearly were by the foundation of the Republic in 509. The Sabine communities outside of Rome (because it is clear they didn’t all move into Rome) were absorbed in 290 and granted citizenship sine suffrago (citizenship without the vote) almost immediately; voting rights came fairly quickly thereafter in 268 BC (Vel. Pat. 1.14.6-7). The speed with which these Sabine communities outside of Rome were admitted to full citizenship speaks, I suspect, to the degree to which the Sabines were already by that point seen as a kindred people (despite the fact that they spoke a language quite different from Latin; Sabine Osco-Umbrian was its own language, albeit in the same language family).

The only group we can say quite clearly that there is no evidence for in early Rome from Livy’s fusion society are the Trojans; there is no trace of Anatolian influence this early (and we might expect the sudden intrusion of meaningful amounts of Anatolian material culture to be really obvious). Which is to say that Aeneas is made up; no great surprise there.

But Livy’s conception of an early Roman community – perhaps at the end of the sixth century rather than in the middle of the eighth – that was already a conglomeration of peoples with different linguistic, ethnic and religious backgrounds is largely confirmed by the evidence. Moreover, layered on top of this are influences that speak to this early Rome’s connectedness to the broader Mediterranean milieu – I’ve mentioned already the presence of Greek cultural products both in Rome and in the area surrounding it. Greek and eastern artistic motifs (the latter likely brought by Phoenician traders) appear with the “Orientalizing” style in the material culture of the area as early as 730 B.C. – no great surprise there either as the Greeks had begun planting colonies in Italy and Sicily by that point and Phoenician traders are clearly active in the region as well. Evidently Carthaginian cultural contacts also existed at an early point; the Romans made a treaty with Carthage in the very first year of the Republic, which almost certainly seems like it must have replaced some older understanding between the Roman king and Carthage (Polybius 3.22.1). Given the trade contacts, it seems likely that there would have been Phoenician merchants in permanent residence in Rome; evidence for such permanently resident Greeks is even stronger.

In short, our evidence suggests that were one to walk the forum of Rome at the dawn of the Republic – the beginning of what we might properly call the historical period for Rome – you might well hear not only Latin, but also Sabine Umbrian, Etruscan and Greek and even Phoenician spoken (to be clear, those are three completely different language families; Umbrian, Latin and Greek are Indo-European languages, Phoenician was a Semitic language and Etruscan is a non-Indo-European language which may be a language isolate – perhaps the modern equivalent might be a street in which English, French, Italian, Chinese and Arabic are all spoken). The objects on sale in the markets might be similarly diverse.

I keep coming back to the languages, by the by, because I want to stress that these really were different people. There is a tendency – we will come back to it next time – for a lot of modern folks to assume that, “Oh well, these are all Italians, right?” But the idea of “Italians” as such didn’t exist yet (and Italy even today isn’t quite so homogeneous as many people outside of it often assume!). And we know that the different languages were mirrored by different religious and cultural practices (although material culture – the “stuff” of daily life, was often shared through trade contacts). Languages thus make a fairly clear and easy marker for a whole range of cultural differences, though – and we will come back to this as well – it is important to remember that people’s identities are often complex; identity is generally a layered, “yes, but also …” affair. I have only glanced over this, but we also see traces of Latin, Etruscan, Greek and Umbrian religious practice in early Roman sanctuaries and our later literary sources; Phoenician influence has also been posited – we know at least that there was a temple to Uni/Astarte in Pyrgi within 30 miles of Rome so Phoenician religious influence could never have been that far away.

We thus have to conclude that Livy is correct on at least one thing: Rome seems to have been a multi-ethnic, diverse place from the beginning with a range of languages, religious practices. Rome was a frontier town at the beginning and it had the wide mix of peoples that one would expect of such a frontier town. It sat at the juncture of Etruria (inhabited by Etruscans) to the north, of Latium (inhabited by Latins) to the South, and of the Apennine mountains (inhabited by Umbrians like the Sabines). At the same time, Rome’s position on the Tiber ford made it the logical place for land-based trade (especially from Greek settlements in Campania, like Cumae, Capua and Neapolis – that is, Naples) to cross the Tiber moving either north or south. Finally, the Tiber River is navigable up to the ford (and the Romans were conscious of the value of this, e.g. Liv 5.54), so Rome was also a natural destination point for seafaring Greek and Phoenician traders looking for a destination to sell their wares. Rome was, in short, far from a homogeneous culture; it was a place where many different peoples meet, even in its very earliest days. Indeed, as we will see, that fact is probably part of what positioned Rome to become the leading city of Italy.

(For those looking to track down some of these archaeological references or get a sense of the source material, though it is now a touch dated, The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol 7.2: The Rise of Rome to 220 B.C., edited by F.W. Walbank, A.E. Astin, M.W. Frederiksen, and R.M. Ogilvie (1990) offers a fairly good overview, particularly the early chapters by Ogilvie, Torelli and Momigliano. For something more suited to regular folks, when I teach this I use M.T. Boatwright, D.J. Gargola, N. Lenski and R.J.A. Talbert, The Romans: From Village To Empire (2012) and it has a decent textbook summary, p. 22-42, covering early Rome with particularly good reference to the archaeology)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans? Part I: Beginnings and Legends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-11.

November 3, 2023

QotD: The use of Epigraphy and Papyrology in interpreting and understanding the ancient and classical world

… let’s say you still have a research question that the ancient sources don’t answer, or only answer very incompletely. Where can you go next? There are a few categories, listed in no particular order.

Let’s start with the most text-like subcategories, beginning with epigraphy. Epigraphy is the study of words carved into durable materials like stone or metal. For cultures that do this (so, Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans: Yes! Gauls, pre-Roman Iberians, ancient Steppe nomads: No!), epigraphy provides new texts to read and unlike the literary texts, we are discovering new epigraphic texts all the time. The downside is that the types of texts we recover epigraphically are generally very limited; mostly what we see are laws, decrees and lists. Narrative accounts of events are very rare, as is the epigraphic preservation of literature (though this does happen, particularly in Mesopotamia with texts written on clay tablets). That makes epigraphy really valuable as a source of legal texts (especially in Greece and Rome), but because the texts in question tend to be very narrowly written (again, we’re talking about a single law or a single decree; imagine trying to understand an act of Congress renaming a post office if you didn’t [know] what Congress was or what a post office was) without a lot of additional context, you often need literary texts to give you the context for the new inscription you are looking at.

The other issue with epigraphy is that it is very difficult to read and use, both because of wear and damage and also because these inscriptions were not always designed with readability in mind (most inscriptions are heavily abbreviated, written INALLCAPSWITHNOSPACESORPUNCTUATIONATALL). Consequently, getting from “stone with some writing on it” to an edited, usable Greek or Latin text generally requires specialists (epigraphers) to reconstruct the text, reconstructing missing words (based on the grammar and context around them) and making sense of what is there. Frankly, skilled epigraphers are practically magicians in terms of being able figure out, for instance, the word that needs to fit in a crack on a stone based on the words around it and the space available. Fortunately, epigraphic texts are published in a fairly complex notation system which clearly delineates the letters that are on the stone itself and those which have been guessed at (which we then all have to learn).

Related to this is papyrology and other related forms of paleography, which is to say the interpretation of bits of writing on other kinds of texts, though for the ancient Mediterranean this mostly means papyrus. The good news is that there is a fairly large corpus of this stuff, which includes a lot of every day documents (tax receipts! personal letters! census returns! literary fragments!). The bad news is that it is almost entirely restricted to Egypt, because while papyrus paper was used far beyond Egypt, it only survives in ultra-dry conditions like the Egyptian desert. Moreover, you have all of these little documents – how do you know if they are typical? Well, you need a very large sample of them. And then we’re back to preservation because the only place you have a very large sample is Egypt, which is strange. Unfortunately, Egypt is quite possibly the strangest place in the Ancient Mediterranean world and so papyrological evidence is frequently plagued by questions of applicability: sure we have good evidence on average household size in Roman Egypt, but how representative is that of the Roman Empire as a whole, given that Egypt is such an unusual place?

Outside of Egypt and a handful of sites (I can think of two) in England? Almost nothing. To top it all off, papyrology shares epigraphy’s problem that these texts are difficult and often require specialists to read and reconstruct them due to damage, old scripts and so on. The major problem is that the quantity of recovered papyrus has vastly outstripped the number of trained papyrologists, bottle-necking this source of evidence (also a lot of ancient papyri get traded on the antiquities black market, potentially destroying their provenance, and there is a special level in hell for people who buy black market antiquities).

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: March 26, 2021 (On the Nature of Ancient Evidence”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-26.

November 2, 2023

Keeping Clean in Rome

seangabb

Published 2 Jul 2023A lecture, given in June 2023, about bathing and keeping clean in the Roman World — plus an overview of depilation and going to the toilet.

(more…)

August 12, 2023

The urge to compare our own culture to the declining Roman Empire

In UnHerd, Alexander Poots wants pundits to stop comparing this or that country in the West to the latter stages of the Gibbonian decline of Rome:

“The Course of Empire – Desolation” by Thomas Cole, one of a series of five paintings created between 1833 and 1836.

Wikimedia Commons.

On both sides of the Atlantic, hysterical comparisons between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the senile polities of the modern West have become the journalistic norm. Every major problem facing our society — from climate change to Covid to inflation — has received the Gibbon treatment.

There are, of course, regional variations. The British, tied by geography to Europe’s fortunes, tend to favour the definitive fall of the Western empire in AD 476. The Americans, ever fearful of an over-mighty executive, linger on the collapse of senatorial authority in 49 BC. And it is also more than a journalistic trope, with the unacknowledged legislators of our world also playing the same game. Elon Musk recently suggested that today’s baby drought is analogous to the low birth rates of Julius Caesar’s dictatorship. Marc Andreessen has compared California to Rome circa AD 250. Joe Rogan, meanwhile, is beginning to suspect that all this gender business might have a worrying ancient precedent.

Such appeals to the past are only human. The fourth word in Virgil’s Aeneid is Troiam. This is the first fact that we learn about Aeneas: he is from Troy. Virgil does not even bother to tell us his hero’s name until the 92nd line. Doubtless, the poets of Ur and Hattusha had their own Troys. And perhaps the first men who placed one mud brick upon another sang of flooded valleys, choked caves and herds that no longer ran. But Rome has been our common loss since the early Middle Ages. As Virgil looked back to Priam, so we look back to Virgil. In 1951, it was perfectly natural for W. H. Auden to compare a dying Britain with a dead Rome: “Caesar’s double-bed is warm / As an unimportant clerk / Writes I DO NOT LIKE MY WORK / On a pink official form”

But journalists and billionaires do not work in a poetic register. They deal in facts and lucre. When they say that Britain or America is following imperium Romanum down the dusty track to oblivion, they seem to be speaking literally. This is not a mistake that Virgil would have made. It is all very well to evoke Rome as an elegiac warning. But if we believe that there are concrete lessons to learn from the Roman Empire’s decline and fall, then we will have to examine the mother of cities as she really was. The results are surprising.

In AD 384, 400 years after Virgil composed his Aeneid, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus had a bridge problem. Symmachus was Urban Prefect of Rome, a role of huge responsibility. By the fourth century, the city of Rome was no longer the imperial capital of the western empire; it had been replaced in 286 by Mediolanum (modern Milan), which was a good deal closer to the empire’s febrile northern borders. But Rome remained the nation’s hearthstone. Her good governance was of the highest priority. The Urban Prefect dispensed justice, organised games, fed the mob and looked after the material fabric of the city. It was not an enviable position. One man had to keep the vast, turbulent metropolis ticking over with the minimum of rioting. Symmachus was well aware of the touchiness of the Roman pleb. His own father had been burned out of his house and chased from the city after making a catty remark of the “let them eat cake” variety during the wine shortage of 375.

The bridge problem went like this. Around 382, the emperor Gratian ordered that a new bridge be built across the Tiber. It soon became clear that construction was taking too long and costing too much. Two years later, as the project neared completion, one span collapsed. Such waste of public funds could not be ignored, and so an inquiry was launched. A specialist diver was engaged to examine the structure; he discovered that the job had been bodged. The engineers responsible for the project, Cyriades and Auxentius, were summoned to account for their failure. Each blamed the other, before Auxentius, who had been caught backfilling sections of the bridge with bales of hay, fled the city — pockets doubtless jingling with public gold.

On the face of it, this sounds like a very late Roman story: a nation once famous for its engineering prowess could no longer build a bridge across the Tiber without everything going horribly wrong. But I’m not sure that’s true. Problems arise all the time, and in themselves tell us very little about a society. What matters is the response to those problems. And Symmachus’s dispatches to the imperial court make it clear that his response was considered and comprehensive. The bridge was completed in the end, and stood for over 1,000 years until its demolition in 1484. Now think of 21st-century London: remember what happened the last time we tried to build a bridge across the Thames?