Timothy Carney says we should know much more about socialist historian Gabriel Kolko and his careful debunking of the “Teddy Roosevelt as trust-buster” myth:

Every American knows the fable of the Progressive Era and that “trust buster” Teddy Roosevelt wielding the big stick of federal power to battle the greedy corporations. We would be better off if more people knew the work of the man who dismantled this myth: historian Gabriel Kolko, who died this month at age 81.

Kolko was a self-described socialist and a Harvard-educated historian, but he had little use for the liberal political establishment’s pious regard for the Progressive Era of 1900 to 1916. And he was never credulous enough to believe that government intervention in the economy was generally in the public interest.

For today’s politics, Kolko’s most important book was The Triumph of Conservatism, published in 1967. His thesis: “The dominant fact of American political life” in the Progressive Period “was that big business led the struggle for the federal regulation of the economy.”

The standard history of the Progressive Period — which painted Teddy and the Feds as the scourge of Big Business — relied too much on the public rhetoric of TR and his cohorts. Kolko dug deeper to show how Big Business truly felt about Big Government, and how the Progressives truly felt about Big Business.

Many corporate titans in the early 20th Century, buying into the pervasive hubris of the day, believed that a state-managed economy was the inevitable end of a rational society — the conclusion of what Standard Oil’s top lobbyist Samuel Dodd called the “march of civilization.” Competition, in their eyes, was destructive redundancy.

[…]

Liberal scholar William Galston at the Brookings Institution explains the economics at play. “Corporations have sizeable cash flows and access to credit markets, which gives them a cushion against adversity and added costs,” he wrote in 2013, explaining why the big guys often welcome regulation. “[S]mall businesses often operate much closer to the margin and are acutely sensitive to policies that threaten to drive up costs.” Also, “CEOs can hire experts to help them cope with added regulatory burdens and can spread the costs over a large workforce.”

Kolko’s research smashed the favorite tales of the Progressive myth. When Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle, which included descriptions of rancid meat-packing plants, Roosevelt saw Sinclair as personally despicable, but a useful asset in his quest to impose federal meat inspection. Sinclair opposed Roosevelt’s regulation, and Kolko relates that “the big packers were warm friends of regulation, especially when it primarily affected their innumerable small competitors.”

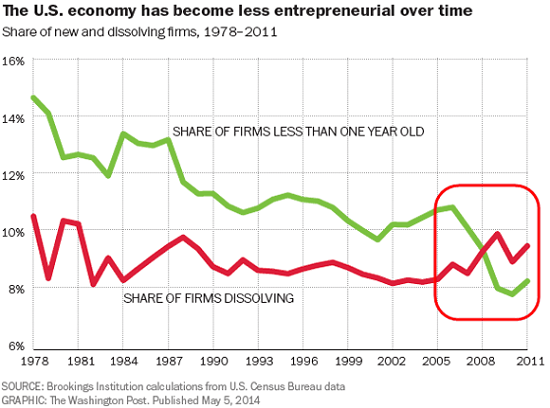

By “conservatism,” Kolko meant “stability,” and preservation of the status quo. This is often the aim of corporate giants. It is consistently the consequence of federal action. And it is reliably the enemy of entrepreneurship, economic growth and free choice.