I can’t tell you now many people I know here in Arizona that tell horror stories about California and how they had to get out, and then, almost in the same breath, complain that the only problem with Arizona is that it does not have all the laws in place that made California unlivable in the first place. They will say, for example, they left California for Arizona because homes here are so much more affordable, and then complain that Phoenix doesn’t have tight enough zoning, or has no open space requirements, or has no affordability set-asides, or whatever. I am amazed by how many otherwise smart people cannot make connections between policy choices and outcomes, preferring instead to judge regulatory decisions solely on their stated intentions, rather than their actual effects.

Warren Meyer, “When You Come Here, Please Don’t Vote for the Same Sh*t That Ruined the Place You Are Leaving”, Coyote Blog, 2016-11-02.

August 20, 2018

QotD: Economic refugees wanting to re-create the hell they just escaped from

August 15, 2018

QotD: State economic intervention in theory and practice

The economic theory: the state intervenes in the economy in order to prevent free-riding – in order to internalize externalities – in order to better ensure that all private parties pay the full marginal costs of their activities, and that all private parties reap the full marginal benefits of their activities – in order to promote competition – in order to protect the weak from the strong.

The political reality: the state intervenes in the economy in order to promote free-riding – in order to externalize costs and benefits that the market has reasonably internalized – in order to better ensure that politically powerful private parties escape the full marginal costs of their activities, and that politically disfavored groups be stripped of much of the marginal benefits of their activities – in order to promote monopoly – in order to render some people weak who are then pillaged by the strong.

Don Boudreaux, “Economists’ Normative Case for Government Intervention is a Very Poor Positive Theory of that Intervention”, Café Hayek, 2016-09-26.

August 14, 2018

Ontario embraces online sales for marijuana, with retail stores to follow in 2019

Chris Selley on the Ontario government’s surprisingly sensible approach to phasing in retail sales of cannabis over the next eight months:

Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government called a brief truce in its multi-front war with the federal Liberals on Monday to give one of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s signature policies a major boost: as had been widely rumoured, the Tories will scrap the previous Liberal government’s tentative public marijuana retail scheme and instead hand out licenses to the private sector.

How many licenses and what kinds of stores are just two of many unresolved details. The government says it will consult widely to determine how best to proceed, with a target opening date for licensed brick-and-mortar stores of April 1, 2019 (with publicly run online sales to commence in October). But it seems safe to hope the cap, if any, will be significantly higher than the previous government’s laughably timid 150.

Thanks to Toronto’s reluctantly laissez-faire approach to illegal storefront (nudge-wink) “medical” marijuana “dispensaries,” we know 150 might not even satisfy a free market in the country’s largest city. Trudeau has always said the goal of legalization was to smash the illegal market and plunk down a legal one in its place. The Ontario Liberals’ plan seemed almost tailor-made to fail in that endeavour.

There remains ample room for the new government to screw this up. But if it gets pricing and regulation and enforcement halfway right, the country’s most populous province should now be well placed to give legalization a good shot at achieving what proponents have always said it should — which is, basically, to make it like booze. Of course kids still get their hands on booze, but at least it’s a bit of a chore. And at least when kids get drunk, they’re not drinking moonshine.

The need to claim the retail market from the existing extra-legal networks will hinge on quality, availability and (especially) the prices that the province sets. Price it too high (pun unintentional), and the legal market will not take over distribution and sales from the black market. Provide poor quality and get the same results. Restrict sales too stringently, and watch the profits go back to the current dealers … who are not noted for their sensibilities about selling drugs to the under-aged.

In the meantime, it’s interesting to ponder why they’re going in this direction. Fedeli and Attorney-General Caroline Mulroney were at great pains Monday to stress their primary concern was the children.

“First and foremost, we want to protect our kids,” said Mulroney. “There will be no compromise, no expense spared, to ensure that our kids will be protected following the legalization of the drug.”

“Under no circumstances — none — will we tolerate anybody sharing, selling or otherwise providing cannabis to anybody under the age of 19,” said Mulroney. Fedeli vowed that even a single sale to a minor would void a retailer’s license.

Yet, let’s be honest, kids well under the age of 19 can already get cannabis and other illicit drugs — more so in urban and suburban areas, but it’s hard to imagine that legalizing cannabis for 19-plus customers somehow magically renders the under-19s uninterested in getting access, too.

July 24, 2018

The impact of licensing on previously unlicensed jobs

In the current Libertarian Enterprise, Sean Gabb looks at the recent outrage at Jeff Bezos and Amazon and recounts how at least one job he’d done in the past is now closed off to casual entrants due to the growth of licensing:

Let us imagine a natural order — that is, a world without states, or at least a world without the extended patterns of state-intervention that now exists. In such a world, wage labour would continue to exist. There are benefits in working for someone else. An employee commits to a contract of permanent service, in return for which he receives reasonable certainty of payment. Not everyone is or wants to be an entrepreneur. Not everyone finds it suitable to keep looking for unsatisfied wants and the most rewarding means of satisfying those wants. This being said, there would probably be much less wage labour than there is now.

If the present order of things does little to deter men like Mr Bezos, it does much to deter little people from starting little businesses — little business that sometimes replace, but more often supplement employed income. When I was much younger, the easiest way I found of making extra money was to drive a mini-cab. I went to the nearest cabbing office. I showed my clean driving licence. I showed a certificate of hire and reward insurance. I handed over £25 rent for the week, and was given a two-way radio and a cabbing number. That evening, I was taking prostitutes to their clients and pushing drunks up their garden paths. You cannot do this nowadays. Cabbing is licensed and regulated. It costs thousands to get a licence, and the regulations about age and type of vehicle add tens of thousands more to the costs of entry. You cannot get into cabbing unless you can pay these entry costs, and unless you are able to pay them back by working there full-time and long-term. A casual business has been made into a profession.

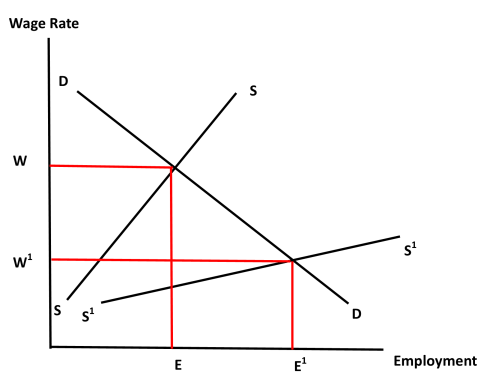

This is an example of which I have personal knowledge. But there is a vast range of little businesses that bring some money to little people. They have nearly all been placed out of reach. The effect is to increase the supply of unskilled labour seeking employment. Think of a supply and demand diagram. Shift the supply curve to the right. Make it more elastic. Money wages will be lower than they would otherwise be. Conditions of work — and these are part of the overall wage — will be worse. Make laws to prevent the market from clearing, and there will be more unemployment.

A further point I mention without choosing to develop is mass-immigration. This is not the kind of movement you would see in a natural order, where virtually the whole cost of entry and adjustment fell on the individual entrant. It is a movement encouraged and subsidised by the State — encouraged by institutional political correctness, and subsidised by laws that amount to forced association. The effect in economic terms is again on the supply curve for labour.

I have no reason to believe that Mr Bezos and Amazon have done anything to bring about this state of affairs. They simply operate in the labour market as they find it. No one is forced to work for Amazon. Amazon is not a legal monopoly, and has no power to force down wages. It pays at least the going rate. It is not a charity, and cannot be expected to behave as a charity. Blaming Amazon for how it pays and treats its workers makes no more sense than blaming a clock for telling the time.

He also touches on the state-created legal situation of limited liability:

I turn to the objection that Amazon is a limited liability company. This is an objection I accept. Limited liability companies exist because of a grant of privilege by the State. They are treated as persons, responsible for their own debts. Their owners have no liability beyond the value of the shares they own. This grant allows companies to gain more investment capital than they otherwise might. It allows them to grow larger and to exist for longer than they otherwise might. It allows even the most entrepreneurial company to turn gradually into a private bureaucracy, trading favours with the various state bureaucracies. Limited liability turns business into the economic arm of a malign ruling class.

So far as Amazon benefits from limited liability, it is an illegitimate enterprise. But this is not the end of the matter. Amazon almost certainly could exist without limited liability. It would instead have raised its investment capital by selling bonds. It would then only be in form what it plainly is in substance — that is, a projection of its owner’s ambition to achieve greatness. It would still have grown large, and it would have grown large by giving its customers what they want.

July 17, 2018

Juul threat

John Tierney on the good news/bad news in the most recent smoking statistics in the United States:

Tobacco-company stocks have plunged this year — along with cigarette sales — because of a wonderful trend: the percentage of people smoking has fallen to a historic low. For the first time, the smoking rate in America has dropped below 15 percent for adults and 8 percent for high school students. But instead of celebrating this trend, public-health activists are working hard to reverse it.

They’ve renewed their campaign against the vaping industry and singled out Juul Labs, the maker of an e-cigarette so effective at weaning smokers from their habit that Wall Street analysts are calling it an existential threat to tobacco companies. In just a few years, Juul has taken over more than half the e-cigarette market thanks to its innovative device, which uses replaceable snap-on pods containing a novel liquid called nicotine salt. Because the Juul’s aerosol vapor delivers nicotine more quickly than other vaping devices, it feels more like a tobacco cigarette, so it appeals to smokers who want nicotine’s benefits (of which there are many) without the toxins and carcinogens in tobacco smoke.

It clearly seems to be the most effective technology ever developed for getting smokers to quit, and there’s no question that it’s far safer than tobacco cigarettes. But activists are so determined to prohibit any use of nicotine that they’re calling Juul a “massive public-health disaster” and have persuaded journalists, Democratic politicians, and federal officials to combat the “Juuling epidemic” among teenagers.

The press has been scaring the public with tales of high schools filled with nicotine fiends desperately puffing on Juuls, but the latest federal survey, released last month, tells a different story. The vaping rate last year among high-school students, a little less than 12 percent, was actually four percentage points lower than in 2015, when Juul was a new product with miniscule sales. As Juul sales soared over the next two years, the number of high-school vapers declined by more than a quarter, and the number of middle-school vapers declined by more than a third — hardly the signs of an epidemic.

July 11, 2018

Environmentalists against science

At Catallaxy Files, Jeff Stier looks at situations when activists who normally fetishize their devotion to science will go out of their way to fight against scientific findings that don’t co-incide with their preferences:

The debate over regulation often devolves into a debate about “too little” versus “too much” regulation, split along the ideological divide. Too little regulation, goes the argument, and we are exposed to too much risk. Too little, and we don’t advance.

This binary approach, however, represents the dark-ages of regulatory policy. It was more frequently relevant when our tools to measure risk were primitive, but today’s technology allows much more precise ways to evaluate real-world risks. With less uncertainty, there’s less of a need to cast a broad regulatory net.

Regulation not warranted by countervailing risk just doesn’t make sense. That’s why a pseudoscientific approach, dubbed the “precautionary principle,” behind much of today’s regulation is so pernicious. This dogma dictates that it’s always better to be safe than to ever be sorry. The approach is politically effective not only because it’s something your mother says, but because it’s easier to envision potential dangers, remote as they may be, than potential benefits. Uncertainty, it turns out, is a powerful tool for those who seek to live in a world without risk.

But what happens when regulators can get a reasonably good handle on benefits and risks? Some potential risks have been eliminated simply because the basis for the concern has proven to be unwarranted. For more than two decades, the artificial sweetener, saccharin, came with a cancer warning label in the U.S.But it turned out that the animal experiment which led to the warning was later found to be irrelevant to humans, and the warning was eventually removed.

Warning about a product when risks are not well-understood is prudent. But it would be absurd to continue to warn after the science tells us there’s nothing to worry about.

Today, an analogous situation is playing out in the EU, where activists are using outmoded tests not just to place warning labels on silicones, a building block of our technological world, but to ban them outright.

The playbook is predictable: as the scientific basis for a product’s safety grows, opponents go to increasingly great lengths to manufacture uncertainty, move the goalposts and capitalize on scientific illiteracy to gain the political upper-hand.

We’ve seen these tactics employed in opposition to everything from growing human tissue in a lab, to harm-reducing alternatives to smoking, such as e-cigarettes. Now, the effort to manufacture uncertainty is playing out in the debate over the environmental impact of silicones, which are used to in a wide range of consumer, medical, and industrial products.

Fortunately, in the case of silicones, regulators in a number of countries, including Australia, have put politics aside and adhere to appropriate scientific methods to inform their decision-making.

July 6, 2018

“That’s what governments are for — get in a man’s way”

Veronique de Rugy says that the 4th of July is a good time to reflect on the American Founding Fathers fighting to gain independence from a distant tyrannical government … and the rest of the year is devoted to coping with a less-distant but no-less tyrannical government in Washington:

Consider the oil and gas industry. Over the years, the federal government has adopted many regulations meant to hinder the industry. As Nick Loris, an energy policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation, reminds me, one such regulation is the Merchant Marine Act, also known as the Jones Act, which makes it more expensive to ship oil and natural gas from coast to coast. Then there are the past administrations’ outright moratoriums on drilling in certain areas of America’s coasts, which massively increases the cost of doing business. As Loris notes, there are many costly bureaucratic delays in issuing leases and processing applications for permits to drill (APDs), which stalls production on federal lands. On average, the federal processing of APDs in the last year of the Obama administration was 257 days, while state processing is typically 30 days or less.

Since Uncle Sam has a lot of regulations in place to make the operations of domestic oil and gas companies more costly, why is the biggest beneficiary of loans from the federal government export credit agency (the U.S. Export-Import Bank) the gigantic Mexico state-owned oil and gas company Pemex? Between 2007 and 2013 (the most complete data set we have), Pemex received over $7 billion in loans backed by American taxpayers to buy U.S. goods. Thanks to Uncle Sam, this discounted borrowing power gives Pemex a leg up on its competition with domestic oil and gas companies.

Then there’s the Trump administration tariffs. These import taxes on foreign goods coming from Europe, China, and other countries have not only raised the cost of doing business but also triggered retaliatory measures from foreign governments. For instance, the farm industry is paying a steep price from the tariffs on steel because they increase the cost of farm machinery, lowering profit margins. Farmers are also hurt by the European, Mexican, Canadian, and Chinese governments that have imposed retaliatory export restrictions on U.S. farm products. Many small farms are calling for help to survive. It’s so bad that the entire Iowa congressional delegation sent a letter to President Trump on June 25 in which it called the tariffs “catastrophic for Iowa’s economy.”

Quote in the headline from Firefly episode “Serenity, Part 1”.

July 4, 2018

June 30, 2018

Enriching the public in ways that do not show up in the GDP calculations

Tim Worstall looks at the calls to regulate the big tech firms and points out that we already get a very good deal on “free stuff” that isn’t reflected in standard economic statistics:

It won’t have escaped your attention that rather large numbers of people are calling for the regulation of the tech companies. The Amazon, Google, Facebook (Apple and Microsoft often added, just because they’re large) nexus have lots of power over markets and thus therefore – well, therefore something. My own prejudice here is that certain people just cannot look at centres of power and or money without insisting that they, the complainers, should be the ones exercising that power and determining the disposition of that money. Thus much of the drive for “democratic” regulation of the economy more generally, the self proclaimed democrats being the ones who would end up with the power. The advantage of this analysis being that it does describe reality, the same people do end up making the same arguments about different companies over time. Mere prominence brings the demand for control.

The economist on this subject is Jean Tirole. His Nobel was for exploring this very subject, tech companies and the two sided market. Google, for example, sells the search engine to us and us to the advertisers. The tech here is different, obviously, but the underlying economics is the same as that of the free newspaper.

Tirole’s a new book out and there are a number of interesting points to be had from it:

Yes, on the whole consumers tend to get a good deal, because we use wonderful services — like Google’s search engine, Gmail, YouTube, and Waze — for free. To be certain, we are not paid for the valuable data we provide to the platforms, as for example Eric Posner and Glen Weyl remind us in their recent book Radical Markets. But on the whole, our living standards have substantially improved thanks to the digital revolution.

From which we can extract a few points. We’re richer, we really are. Substantially richer and yet in a manner that normal economic statistics entirely fail to capture. As Hal Varian has pointed out, GDP doesn’t deal well with free. Near all of those benefits of the digital revolution are coming to us for free and so aren’t recorded in that GDP. So, we’re richer yet the numbers say we’re not. In that is much of the explanation of slow economic growth these days, even of slow real wage growth. We’re just not counting what is happening to our living standards.

But we can and should go further than that. If the above is true then we’re very much less unequal than we’re recording. Stuff that’s free is, obviously enough, distributed rather more evenly among the population than extant monetary incomes. You, me and Bill Gates all have access to exactly the same amount of Facebook at the same price. We’re entirely equal in that sense. Bill’s actually poorer concerning search engines, stuck for emotional reasons with Bing as he is while we get to use Google or DuckDuckGo. Our standard measures of inequality are wrong both because of the undermeasurement of new wealth and also the extremely equitable pattern of the distribution of that new wealth.

QotD: In government regulations, complexity is a subsidy to existing companies

One of the major themes of the book I’m working on should be familiar to longtime readers of this “news”letter. It boils down to a simple insight: Complexity is a subsidy. The more complex you make the rules, the more you reward people with the cognitive, material, or social resources necessary to get around them. Big corporations tend not to object to more burdensome regulations because they can afford to comply with them. Dodd-Frank was great for the “too big to fail” crowd. But it has been murder on community banks that don’t have the resources to comply. As Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, put it:

It’s very hard for outside entrants to come in and disrupt our business simply because we’re so regulated. We hear people in our industry talk about the regulation, and they talk about it with a sigh about the burdensome of regulation. But in fact in some cases the burdensome regulation acts as a bit of a moat around our business.

But you’ve been hearing this stuff from me for years. Let’s get back to the arrogance thing. It seems to me a big part of the problem with progressive elites these days is that they lack self-awareness. That elites arrange affairs for their own self-interest is an insight that was already ancient when Robert Michels penned his Iron Law of Oligarchy. But ever since the progressives concocted their theories of “disinterestedness,” they’ve convinced themselves that they are not in fact a self-serving elite. Give feudal aristocrats their due: They were a self-dealing crop of rent-seekers and exploiters, but at least they were open about the fact that they believed they had a divine right to sit atop the social pyramid. Today’s progressive aristocracy is largely blind to the fact that their cult of expertise isn’t really about expertise; it’s about organizing society in a way that reinforces their status and power.

Well, most of them are blind to it. Occasionally the mask slips. Jonathan Gruber, one of the chief architects and financial beneficiaries of the health-care “reform,” told audiences that Obamacare was designed “in a tortured way” to hide the fact that “healthy people pay in and sick people get money.” They had to do it this way to get around the inconvenient “stupidity of the American voter.” A feudal lord who talked this way about his serfs wouldn’t get any grief for it. But in America such honesty gets you rendered an un-person.

Jonah Goldberg, “The Consequences of Overpromising on Obamacare”, National Review, 2016-10-08.

June 25, 2018

Differences between the United States and the “idealized” United States of Europe

Tim Worstall, in the Continental Telegraph:

There are those who think – urge, wish for perhaps – the European Union is or should become the United States of Europe. Lots of central bureaucratic control, the nation states left as just the remnants of once independent countries like the US states are these days. In some ways the two systems are very much the same already. No US state has any control at all over trade across its own border. Nor does any EU one. Trade is an issue solely the competence of the central organisations, respectively Washington DC and Brussels. Equally, both systems use this central control of trade and trade only to expand that central control.

In the US there was a case that Federal control of trade meant that the Feds got to decide who could grow wheat where and when. The usual sort of planning idiocy led to the Feds telling farmers who could grow how much and when. One farmer claimed he was only growing for his own consumption and this shouldn’t be limited. The centre (the Supreme Court) disagreed, the crux being that if he didn’t grow for his own consumption he would buy, this affected inter-state commerce, he had to obey the Feds. The EU takes this a step further. The Single Market rules are nominally about trade. Anything legal to be buying and selling in one place is such in all is a reasonable explanation of the nub of the matter. Sure, exceptions and all that. But this then smuggles into all law that continental (Roman Law really) idea that what is legal to do is something that the legislation defines. Instead of that Common Law idea that legislation, the law even, defines what it is illegal to do all other things being legal.

Once this is accepted then of course the next step is that there must be regulation of all things so as to tell people what it is legal to do. In this manner all sorts of things get smuggled in. Vacuum cleaner motors must be limited to a certain size or power. Because those whose lives are unfortunate enough that they’ve time to spare to be concerned about legislation on such matters note that they can be and thus incorporate their trivialities into legislation. The extent of this reach is larger than you think. The underlying legal, not political, justification for recycling targets is that some countries – Holland, where digging a hole gains nothing but wet boots – don’t have space for landfill. This would put them at a disadvantage if other countries do have the space, therefore all must recycle.

Giving the centre power always, but always, means an extension of the centre’s power. The two systems aren’t so different then.

June 5, 2018

Down with the experts!

In Quillette, Alex Smith explores the limits of expertise and why so many people today would eagerly agree with the sentiments in my headline:

“People are sick of experts.” These infamous and much-derided words uttered by UK Conservative parliamentarian Michael Gove express a sentiment with which we are now probably all familiar. It has come to represent a sign of the times — either an indictment or a celebration (depending on one’s political point of view) of our current age.

Certainly, the disdain for expertise and its promised consequences have been highly alarming for many people. They are woven through various controversial and destabilising phenomena from Trump, to Brexit, to fake news, to the generally ‘anti-elitist’ tone that characterises populist politics and much contemporary discourse. And this attitude stands in stark contrast to the unspoken but assumed Obama-era doctrine of “let the experts figure it out”; an idea that had a palpable End of History feeling about it, and that makes this abrupt reversion to ignorance all the more startling.

The majority of educated people are fairly unequivocal in their belief that this rebound is a bad thing, and as such many influential voices — Quillette‘s included — have been doing their best to restore the value of expertise to our society. The nobility of this ambition is quite obvious. Why on earth would we not want to take decisions informed by the most qualified opinions? However, it is within this obviousness that the danger lies.

I want to propose that high expertise, whilst generally beneficial, also has the capacity in certain circumstances to be pathological as well — and that if we don’t recognise this and correct for it, then we will continue down our current path of drowning its benefits with its problems. In short, if you want to profit from expertise, you must tame it first.

[…]

However, it is worth drawing a distinction between these two types of expertise — the kind people question, and the kind people don’t. In short, people value expertise in closed systems, but are distrustful of expertise in open systems. A typical example of a closed system would be a car engine or a knee joint. These are semi-complex systems with ‘walls’ — that is to say, they are self-contained and are relatively incubated from the chaos of the outside world. As such, human beings are generally capable of wrapping their heads around the possible variables within them, and can therefore control them to a largely predictable degree. Engineers, surgeons, pilots, all these kinds of ‘trusted’ experts operate in closed systems.

Open systems, on the other hand, are those that are ‘exposed to the elements,’ so to speak. They have no walls and are therefore essentially chaotic, with far more variables than any person could ever hope to grasp. The economy is an open system. So is climate. So are politics. No matter how much you know about these things, there is not only always more to know, but there is also an utterly unpredictable slide towards chaos as these things interact.

The erosion of trust in expertise has arisen exclusively from experts in open systems mistakenly believing that they know enough to either predict those systems or — worse — control them. This is an almost perfect definition of hubris, an idea as old as consciousness itself. Man cannot control nature, and open systems are by definition natural systems. No master of open systems has ever succeeded — they have only failed less catastrophically than their counterparts.

May 9, 2018

Freedom of the Press … except where prohibited by (British) law

Wednesday is a critical day in the history of Britain, in the sense that a long-established freedom is at risk of being curtailed:

Press freedom is hanging by a thread in Britain. Tomorrow, the House of Commons will vote on the Data Protection Bill, and Labour MPs have added amendments to it that would effectively end 300 years of press freedom in this country.

That this profound affront to liberty had almost passed under the radar, until spiked and others began making noise about it over the weekend, shouldn’t surprise us. This vote is the culmination of a slow and covert war on the press that has been waged for the best part of a decade.

This story begins with the Leveson Inquiry, an effective showtrial of the press that sparked dozens of spurious trials of journalists and barely any convictions. Since then, press-regulation campaigners have had to find new and underhand ways to push their agenda on an industry and a public who clearly see right through it.

In the wake of Leveson, a new regulator, Impress, was established and given official recognition. It was an historic moment, in the worst possible sense: this was Britain’s first state-backed regulator since the days of Crown licensing. But it was also a stunningly bad bit of PR for the press-regulation lobby, in that Impress was staffed by tabloid-loathing hackademics and funded by tabloid-loathing millionaire Max Mosley.

No national newspaper signed up to it. And so the Hacked Off brigade has been pushing over the past few years for Section 40, a law that would force publications to sign up to a state-approved regulator, which at the moment means signing up to Impress. Those publications, like spiked, who would refuse on principle, would be required to pay the legal costs of any case brought against them, even if they win.

As such, Section 40 would be a gift to the powerful and the begrudged. It would enable anyone to launch lawsuits aimed at shutting down publications they dislike. This is an opportunity that people who have been exposed by the press would take in a heartbeat. It would undermine not only press freedom, but also natural justice.

And it isn’t just the press who are concerned about this. In 2016, the government opened a public consultation into press freedom, asking members of the public if it should implement Section 40 and commence the second part of the Leveson Inquiry. Out of a huge 174,730 responses, 79 per cent said No to Section 40 and 66 per cent said No to Leveson 2.

Update, 10 May: The vote was too damned close, but it was defeated by a nine-vote margin. Guido has the list of MPs voting in favour of muzzling the press here.

May 5, 2018

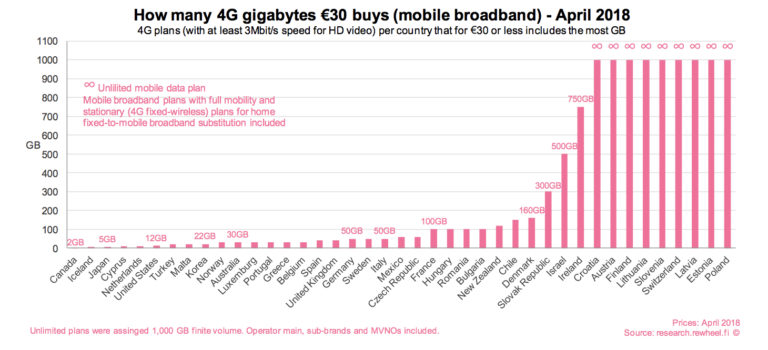

Canada is #1 in the world! In the ripping-off-the-wireless-user sweepstakes!

This is the sort of thing that isn’t really surprising — if you’re a Canadian wireless data user — but puts it into a sad, sad perspective:

The sad state of Canadian wireless pricing is old news for consumers and the government, but a new report graphically demonstrates how Canadians face some of the least competitive pricing in the developed world. The Rewheel study measured pricing in EU and OECD markets by examining how many gigabytes of 4G wireless data consumers get for the equivalent of 30 euros. This chart from Rewheel says it all:

Canada is at the far left of the chart with consumers getting less for their money than anyone else. While many countries offer unlimited mobile data at that price, the report says Canadian carriers offer a measly 2 GB. The smartphone data plans aren’t much better, with nearly all countries offering better deals and many shifting to unlimited data at that price.

[…]

In addition to outrageously expensive wireless data plans, Canadians also face huge overage charges (more than a billion dollars per year generated in the wireless overage cash grab) and steadily increasing roaming charges. Yet when it came to introducing greater resale competition, the CRTC rejected new measures that it admitted could result in some improvement to affordability.

QotD: Making decisions for other people’s “best interests”

Confession: ever since I began to study economics as an 18-year old, I’ve always had difficulty understanding the thought processes of people who fancy themselves fit to intervene into the affairs of other adults in ways that will improve the lives of other adults as judged by these other adults. I understand the desire to help others, and I also understand that individuals often err in the pursuit of their own best interests. What I don’t understand is Jones’s presumption that he, who is a stranger to Smith, can know enough to force Smith to modify his behavior in ways that will improve Smith’s long-term well-being. Honestly, such a presumption has struck me for all of my adult life as being so preposterous as to be inexplicable. I cannot begin to get my head around it.

I cannot get my head around Jones’s presumption that he knows enough to forcibly prohibit Smith from working for an hourly wage lower than one that Jones divines is best for Smith. I cannot understand Jones’s presumption that he ‘knows’ that Smith meant, but somehow failed, to bargain for family leave in her employment contract. I am utterly befuddled by Jones’s presumption to know that the pleasure that Smith gets from smoking cigarettes is worth less to Smith than is the cost that Smith pays to smoke cigarettes. I cannot fathom why Jones presumes that he knows better than does Smith how Smith should educate her children.

Yet this presumption is possessed by many, perhaps even most, people. Why?

Don Boudreaux, “A Pitch for Humility”, Café Hayek, 2016-08-05.