The Great War

Published on 2 Apr 2019It’s time for another episode of Beyond The Great War where we answer questions from the community. This time we take a look at the Greater Poland Uprising and the situation of Poland in early 1919, Jesse recommends a few of his favourite history books and we also talk about how veterans were treated after the 1918 armistice.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar

Merchandise: https://shop.spreadshirt.de/thegreatwar/» SOURCES

Boysen, Jens. “Polish-German Border Conflict”, in 1914-1918 online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online…Davies, Norman. White Eagle, Red Star. The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920 and the ‘Miracle on the Vistula’ (London: Pimlico, 2003 [1972]).

Gattrell, Peter. Russia’s First World War (Pearson, 2005).

Gerwarth, Robert. The Vanquished. Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917-1923 (Penguin, 2017).

Horne, John. “The Living,” in Jay Winter, ed. The Cambridge History of the First World War, vol. 3: Civil Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014): 592-617.

Leonhard, Jörn. Der überforderte Frieden. Versailles und die Welt 1918-1923 (CH Beck, 2018).

Pawlowsky, Verena/Wendelin, Harald. “Government Care of War Widows and Disabled Veterans after World War I,” in: Contemporary Austrian Studies, XIX: From Empire to Republic: Post-World War I Austria, eds. Bischof, Günter/Plasser, Fritz/Berger, Peter (2010): 171-191

Prost, Antoine. “Les anciens combattants”, in Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Jean-Jacques Becker, eds. Encyclopédie de la Grande guerre 1914-1918 (Paris: Bayard, 2013): 1025-1036.

Snyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (Yale University Press, 2003).

April 3, 2019

Greater Poland Uprising – Book Picks – Veteran Care I BEYOND THE GREAT WAR

March 12, 2019

A choice between a (small) UBI and not taxing the poor at all

Tim Worstall responds to an article advocating abolishing Britain’s tax-free personal allowance and replacing it with a form of universal basic income (UBI):

Sure, we need to have government, even if not quite as much as we do have. Thus we need tax revenues to pay for it. But that tax should be, where it is derived from income, paid by the better off among us. As Adam Smith pointed out, people should be paying more than in proportion to their income. I would actually argue that income tax should only kick in at median income but agree that would require a smaller state than we’ve got now. Actually, that’s why I would propose it.

Still, that does mean that this suggestion fails at that first hurdle:

The tax-free personal allowance, which rises to £12,500 in April, should be scrapped and replaced with a flat payment of £48 a week for every adult, according to radical proposals welcomed by shadow chancellor John McDonnell. The proposal, from the New Economics Foundation thinktank, is for a £48.08 “weekly national allowance,” amounting to £2,500.16 a year from the state, paid to every adult over the age of 18 earning less than £125,000 a year. The cash would not replace benefits and would not depend on employment.

It’s a universal basic income. Excellent stuff therefore. But the error is to think that this should replace that personal allowance. Assume that they’re including NI in that no allowance thing – if they’re doing it for income tax then they probably will for NI. What that means is that anyone earning more than £50 a week is facing a 40% marginal tax rate (yes, 40%, employers’ NI is incident upon the workers’ wages).

Do we think that’s a just way to pay for diversity advisers? That someone on £50 a week gives up 40% of any income over that? No, we don’t, we think that’s an entirely unjust taxation system. Actually, it’s a really stercore* taxation system.

* Someone’s been at his Latin texts again … I had to look this word up myself. It’s the ablative singular form of stercus, which means “manure, dung; to sully, soil, decay”, according to Wiktionary.

March 10, 2019

Irish Potato Famine – The American Wake – Extra History – #4

Extra Credits

Published on 9 Mar 2019Not all of the 214,000 Irish immigrants in 1847 made it safely to their new homes — and of those who did, many faced classism and xenophobia and even bullying from the “Ulster Irish” or “Scots-Irish” folks who had previously established themselves. In New York City specifically, the Five Points neighborhood became an infamous center of conflict — while local Irish-American John Joseph Hughes became instrumental in restoring Irish Catholicism.

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

February 28, 2019

The federal Liberals did get one important thing right … no, not marijuana legalization

Justin Trudeau’s Liberals haven’t had a lot of successes in their term in office, but there is one achievement they can legitimately take some credit for:

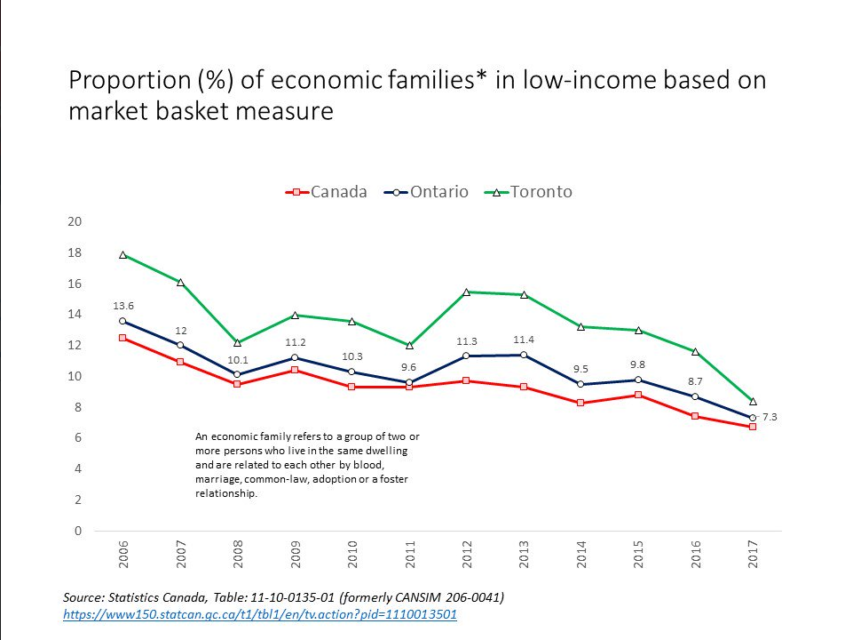

Pssst. Can I let you in on a little secret? Keep it under your hat, but — the poverty rate has fallen again. In fact, it’s at a new all-time low. Statistics Canada reports that the percentage of Canadians falling below the official poverty line in 2017 fell to 9.5 per cent, down from 15.6 per cent in 2006. That still leaves much room for improvement. But this is remarkable progress.

Of course, the official measure of poverty, known as the Market Basket Measure, has only been around for a few years. But an earlier, unofficial measure, known as the Low Income Cut Off, goes back much further. It, too, is at an all-time low, after a steady, two decades-long decline. Indeed, at 7.8 per cent, it’s barely half what it was in 1996.

Andrew Coyne continues:

The sources of this amazing success story are not hard to find — and no, it is not quite as simple a matter as replacing the Conservatives with the Liberals. The trendlines on both low and median incomes, I repeat, go back to the mid-1990s: when the economy, after the long recession, began to grow again.

It turns out — who knew — that poverty tends to fall, and incomes to rise, in periods of economic growth, such as we have enjoyed, almost without interruption, since then. Even the 2009 recession, a relatively mild one in Canada, barely made a dent in either trend.

Still, the Liberals deserve some credit for the continuing decline in poverty since they were elected. If the overall rate has dropped appreciably, it has fallen even more among children — especially welcome, given the lasting effects poverty can have on life chances. At nine per cent, it is down a third from just two years ago.

That’s almost certainly due, at least in part, to the Liberals’ first and most significant policy reform: the rationalization of several existing child benefits and credits into a single income-tested Canada Child Benefit, with increased amounts going to low-income families. It turns out — who knew — that if you give people more money, they are less likely to be in poverty.

February 18, 2019

Mis-measuring inequality

Tim Worstall explains why any protest in a western country about “inequality” is probably bogus from the get-go:

Their opening line, their justification:

We live in an age of astonishing inequality.

No, we don’t. We live in an age of astonishing and increasing equality. Thus any set of policies, any series of analysis, that flows from this misunderstanding of reality is going to be wrong.

And that’s all we really need to know about it all.

The problem is that their measurements – the ones they’re paying attention to – of inequality just aren’t the useful ones, the ones we’re interested in. They’re usually pre-tax, pre-benefits. They’re always pre-government supplied services. And they never, ever, look at the thing we’re actually interested in, inequality of living standards.

To give an example, the Trades Union Congress did a calculation a few years back looking at top 10% households in the UK and bottom 10%. They took the average of each decile – so, the average of the top 10% households, the average of the bottom. Then they looked at the ratio between them.

The top 10% gain some 12 times the market income of the bottom 10%. Now take account of taxes and benefits. Then add in the effects of the NHS, free education for all children and so on. Government services. We end up with a ratio of 4 to 1. Life as it’s actually lived gives the top 10% four times the final income – income being defined by consumption of course – of the bottom 10%.

That’s not a high level of inequality.

December 29, 2018

Helping Africa become less poor

In the Washington Examiner, Tim Worstall explains how and why Africans will benefit from adopting western agricultural methods:

No doubt much to the annoyance of the real farming types, Africa is starting to adopt American industrial farming practices. Thankfully, this is going to make Africa and its residents vastly richer. Tyson (that enemy of everything the organic and slow-food movements hold dear) is working and investing to bring the U.S. system of broiler chicken production to the world’s poorest continent, thereby making it less poor.

[…]

To an economist, everything is a technology. A supermarket is a technology, a mobile phone system, medieval peasantry is a technology, and so is battery farming of broiler hens. A technology is a method of doing something and battery farming is a more advanced, because it’s more productive, technology than the medieval techniques. Most of Africa would be overjoyed to have something as productive as that peasantry our own forefathers suffered through.

Places and people are poor because they use older and less productive technologies. As Paul Krugman’s possibly finest essay points out (and his finest is very good indeed), when a place is using technologies as productive as a richer place, then those users are as rich. That’s just the definition: We’re richer if we get more output from our input of labor. Adopt technologies that are more productive, and we become richer.

The reason places like Africa are poor is not because of capitalism, exploitation, the residues of colonialization, or even the long, dark shadow of the slave trade. Nor is it poor even because of idiotic socialism or the propensity of politicians to run off with the national treasury. You can blame any selection of those as you wish, and with some of them you’d even be right, but they are all proximate causes. The ultimate reason is simply that poor places are using less productive technologies, richer ones more productive. All of those varied things can be blamed for reducing the use of more advanced technologies, but it is the lack of technological advance itself that causes the poverty.

December 20, 2018

QotD: An “authentic” peasant diet

The fact is that you wouldn’t want to eat like a European peasant of yesteryear, or a Chinese peasant, either. Sure, peasants ate well when the garden was producing and the harvest was ripe. A lot of the year, they ate pretty meager, dull fare. Many of the spices we now take as ordinary — salt and pepper, for example — were pretty pricey. So were meat and cheese, which, like everything else, tended to get pretty scarce in winter. When you read about what people were actually eating most of the year, you realize that diets were dull, repetitive, and heavy on grains and legumes, lightly complimented by salted and dried things (home canning, like many of the other things we think of as traditional, was another Industrial Revolution contribution, and before modern farming practices, cows tended to be “dried off” in the winter to save the expense of the extra feed a milking cow needed). And this stayed true throughout the 19th century for large swaths of the population in both America and abroad.

The farther north you went, the more this was true — it’s probably no accident that Ireland and Scandinavia are not, let us say, renowned for their fantastic contributions to world cuisine. When your growing season is a short cloudy period between miserable winters, you don’t have the raw materials to construct amazing dining experiences. (Sure, every country has at least one or two really good fairly traditional foods. But the shorter the time fresh ingredients are available, the fewer culinary marvels you’ll be able to produce.)

Too, we must remember that not everyone was a good cook. Cooking was a job, not an absorbing hobby, and as with any other job, many people did it badly. Every farm wife could produce enough calories to feed her family (at least, if the raw materials were available). Not all of them could produce anything you’d want to eat. Modern food-processing technology has relieved us of that most “authentic” culinary experience: boring ingredients processed by an indifferent cook into something that you’d only voluntarily consume if you were pretty hungry. Even the memory of these cooks has fallen away, though you’ll encounter a lot of them if you read old novels.

Megan McArdle, “‘Authentic’ Food Is Not What You Think It Is”, Bloomberg View, 2017-02-24.

November 19, 2018

“You call someplace paradise/kiss it goodbye”

The Eagles song “The Last Resort” references a generic paradise, not the California town of that name, yet it fits disturbingly well, as Gerard Vanderleun describes:

Paradise is not a town on some flat land out on the prairies or deep in the desert. Paradise is a series of cleared areas and roads superimposed on an extremely rugged terrain composed of deep, narrow ravines and high and densely wood ridges. The Skyway is fed by hundreds of paved and unpaved roads that twist and turn and rise and dip and then, at their OFFICIAL ends, run deeper still and far off the grid. If you live in Paradise you know there are hundreds of people living back up in those ravines and ridges that would be hard to find before the fire. In those places, the poor are lodged tighter than ticks.

I’ve seen, before the fire this time, people in the outback of Paradise so abidingly poor they were living in trailers from the 70s resting on cinder blocks and at most only two winters away from a pile of rust. These people would have had no warning of a fire, no warning at all. Instead of “sheltering in place” they would have been “incinerated in place.”

In the ravines and forests of Paradise, cell reception was so spotty that AT&T gave me my own personal internet driven cell-phone tower. If those off the grid in Paradise actually owned cell phones they would have been lucky to get an alert. But most of those did not own cell phones, and landlines didn’t run that deep in the woods. When the fire closed over them they would have had no warning. No warning until the trailer melted around them. And then there was, out behind but still close to their trailer, their large propane tank.

October 24, 2018

Temporal privilege

In the latest issue of Libertarian Enterprise, Sarah Hoyt discusses reading a recent historical novel that she nearly threw at the wall:

What brought about this rant is that I just read a Pride and Prejudice Variation written by someone who swallowed Dickens hook line and barbed socialist sinker.

Dickens was an amazing writer. What he was not was an historian or an impartial observer. What he put in his books has tainted people’s perception of the past and encouraged the cardinal “socialist virtue” of envy. It causes people to think those richer than themselves are callous bastards. It teaches people to see the past through that lens.

This book was almost walled when the woman assured us that the middle and upper classes did not care about the disappearance of a serving-woman.

It wasn’t many years after that the murder of a series of prostitutes set Victorian England aflutter, and yes, that included the upper and middle classes.

In the same way she waxes pathetic about how death was common among the poor in the Regency. B*tch, death was common in the Regency, period. If your entitled, propagandized ass were plopped down in a society with no antibiotics and uncertain house-heating, you’d learn really quickly how common. Young ladies in the upper reaches of society routinely made two baby shrouds as part of their trousseau. They were expected to lose at least that many children. And while we’re talking of children, yeah, death in child birth was really common too. As was death in any of the male occupations which, as is true throughout history, took them outside the house. Even noblemen were around horses a lot, and spent quite a bit of time — if they were worth their salt — managing their own lands, fraught occupations in a time when any wound could turn “septic” and any cold could turn “putrid” and carry you off.

Yeah. The people in these close-to-the-bone societies didn’t give money to people who’d waste it. They sometimes set conditions on distributing largesse. And they had definite opinions on what behaviors were “good” and which “bad.”

They weren’t tight-ass moralists, as the left imagines. They were following precepts and behaviors proven to lead to success. Mostly success in staying alive.

They were poorer than us and in that measure they were a lot more realistic.

They had to be. The other way lay death.

Spitting on our ancestors for not obsessing about gender-fluid trilobites is in fact the ultimate expression of “temporal privilege.” The left is yelling at people poorer, unhealthier and less able than themselves.

And they’re proud of it.

October 16, 2018

Fast food outlets cluster in poorer areas – because they’re low-margin businesses

Tim Worstall debunks the “fast food restaurants are preying on the poor” myth:

Contrary to the musings of Rod Liddle in the Sunday Times there is a cause and effect going on over the placings of fast food restaurants or outlets in British towns. The provision of burnt chicken and maybemeatburgers to the hoi polloi is a hugely competitive business. This means that it is also low margin. So, where do you put the places that are in a low margin line of business?

[…] this is about clustering of those nosh joints. Why are they in the poor areas? Well, for the same reason the poor are in the poor areas. They’re cheap. This being rather the defining point about poor people, they look for cheap places to live. The two are therefore synonymous, poor and cheap. And what is it we’ve just said about nosh? That it’s a low margin business. Therefore purveyors of the deep fried and battered saveloy – that joy of the ages – are going to be clustered in the poor part of town where they can afford the rents.

And that’s our cause and effect. Some poor people are poor because they’re, or have been, ill. They’re in the cheap part of town because they’re poor. Fried gut shops are in poor areas because they don’t make much money therefore they’re in the poor part of town. Absolutely any analysis of the phenomenon which doesn’t account for this is wrong. And no analysis done by anyone does take account of it – therefore all current analyses of the point are indeed wrong.

There are also other factors to consider, including the fact that poor people are less likely to have the ability or facilities to prepare their own meals (or the habit of cooking for themselves), so the easy availability of high-calorie fast food or snacks is rather important to them. When you’re hungry and don’t have a fridge or freezer full of food at home, a burger or fried chicken has a much stronger appeal than it does to more wealthy folks with well-stocked pantries. If you’ve been raised on high-fat/high-salt foods, the “healthier” alternatives may not appeal, as they also are less flavourful than their fast food options.

September 26, 2018

The New York Times on the minimum wage question

Jon Miltimore shares the key points of a New York Times editorial on the minimum wage:

The minimum wage is the Jason Vorhees of economics. It just won’t die.

No matter how many jobs the minimum wage destroys, no matter how many times you debunk it, it always comes back to wreak more havoc.

We’ve covered the issues at length at FEE, and quite effectively, if I do say so myself. But I have to admit that one of the greatest takedowns of the minimum wage you’ll ever find comes from an unlikely place: The New York Times.

There are many reasons people and politicians find the minimum wage attractive, of course. But the Times, in an editorial entitled “The Right Minimum Wage: 0.00,” skillfully rebuts each of these reasons in turn.

Noting that the federal minimum wage has been frozen for some six years, the Times admits that it’s no wonder that organized labor is pressuring politicians to increase the federal minimum wage to raise the standard of living for poorer working Americans.

“No wonder. But still a mistake,” the Times explains. “There’s a virtual consensus among economists that the minimum wage is an idea whose time has passed.”

But why has the idea “passed”? Why would raising the minimum wage not help the working poor?

“Raising the minimum wage by a substantial amount would price working poor people out of the job market,” the editors explain.

But wouldn’t the minimum wage increase the purchasing power of low-income Americans? Wouldn’t a meaningful increase allow a single breadwinner to support a family of three and actually be above the official U.S. poverty line?

Ideally, yes. But there are unseen problems, as the editors point out:

There are catches…[A higher minimum wage] would increase employers’ incentives to evade the law, expanding the underground economy. More important, it would increase unemployment: Raise the legal minimum price of labor above the productivity of the least skilled workers and fewer will be hired.

But if that’s true, why would progressives support such a law? What’s their rationale for supporting a minimum wage if it does more harm than good? Is it sheer political opportunism?

Not necessarily. The Times explains:

A higher minimum would undoubtedly raise the living standard of the majority of low-wage workers who could keep their jobs. That gain, it is argued, would justify the sacrifice of the minority who became unemployable.

There’s just one problem with this logic, the editors say:

The argument isn’t convincing. Those at greatest risk from a higher minimum would be young, poor workers, who already face formidable barriers to getting and keeping jobs. The idea of using a minimum wage to overcome poverty is old, honorable – and fundamentally flawed. It’s time to put this hoary debate behind us, and find a better way to improve the lives of people who work very hard for very little.

September 9, 2018

QotD: Minimum wages hurt the very poorest workers

The theory that minimum wages discharged the least productive workers had been a constant of Anglophone political economy, dating to John Stuart Mill’s (1848) Principles of Political Economy. When England established a minimum wage with the Trades Board Act in 1909, it did so notwithstanding the objections of a generation of England’s most eminent economists – Henry Sidgwick, Alfred Marshall, Philip Wicksteed, and A.C. Pigou – all of whom observed that while the law could make it criminal to pay a worker less than the minimum, it could not compel firms to hire someone at that rate. Even the intellectual champions of the English minimum wage conceded the point.

Thomas Leonard, Illiberal Reformers, 2016.

August 19, 2018

Poor whites in the pre-Civil War South

Colby Cosh retweeted this fascinating thread by Keri Leigh Merritt (embed through the ThreadReaderApp):

August 5, 2018

August 4, 2018

Violence against women

Joanna Williams on the problem that well-established, well-paid, financially secure women — at least the professional feminists fitting those criteria — are having to work very hard to maintain their air of victimhood:

Being a feminist must be hard work. Perhaps you’ve got a newspaper column to fill with your hot take on the latest sexist outrage. Or perhaps you have a university sexual-harassment policy to write. Or a government minister to consult about a proposed new law. Or a hefty budget to administer. You’ve got the salary, a platform for your views, and the capacity to influence what happens in almost every institution in the country. And yet the entire basis for you being in this fortunate position, for walking the corridors of power, is your powerlessness. The bind for today’s professional feminist is the more power and influence she gains, the harder she needs to work to show that women are still oppressed.

[…]

As feminists increasingly take positions of power, tackling violence against women drives their agenda. The World Health Organisation tells us that violence against women ‘is a major public-health problem’. The United Nations tells us it is ‘a grave violation of human rights’. The British government describes violence ‘against women and girls’ as a serious crime that has ‘a huge impact on our economy, health services, and the criminal-justice system’.

Of course, violence against women and girls deserves to be taken seriously and perpetrators should be severely punished. But the lives of women in poverty-stricken and wartorn countries are very different to those of women in England. Likewise, adult women have far more agency and control over their lives than girls. Conflating the experiences of women all around the world, and of adult women with children, allows professional feminists to claim suffering by proxy.

At the same time, the definition of violence seems to broaden by the day. The internationally agreed definition of violence against women and girls is: ‘Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women [or girls], including threats of such acts.’ In the UK and the US, violence encompasses sexual harassment – which includes winking, whistling and looking at someone for too long. Amnesty International describes women’s experiences of ‘violence and abuse on Twitter’. In 2017, the organisers of a women’s strike against President Trump described ‘the violence of the market, of debt, of capitalist property relations, and of the state; the violence of discriminatory policies against lesbian, trans and queer women’.

This is not violence as a physical act, but violence as metaphor. No wonder it is experienced everywhere. The World Health Organisation describes violence against women as an ‘epidemic’. We are told that over a third of girls have been sexually harassed at school and that more than a third of women have experienced sexual harassment at work. But then we also learn that two women are killed each week by a current or former partner. And here, immediately, is the problem with violence as metaphor. Real violence becomes relativised. When winking and nasty tweets are described as acts of violence, the word is no longer enough to describe acts of physical brutality and murder. Violence has become nothing more than a badge permitting membership of an inclusive feminist club, and this does little to support women who really are in need of help.