Published on Mar 18, 2017

When Ned Kelly lost his father at a young age, he became the man of the house but didn’t know how to support his family. Swept up by the grandiose tales of a visiting bushranger, young Ned decided to give crime a try.

April 8, 2017

Ned Kelly – I: Becoming a Bushranger – Extra History

March 9, 2017

Words & Numbers: Women Prosper When Markets Are Free

Published on 8 Mar 2017

This week, in honor of International Women’s Day, Antony & James discuss the strong correlation between economic freedom and gender equality found across the world. They argue that if you want to see a world of increasing equality and opportunity for women, you also want to free the economy from central planning and control.

March 2, 2017

Words & Numbers: The Problem with Alternative Facts

Published on 1 Mar 2017

I this week’s episode, Antony & James talk about alternative facts and how false, partisan data skews important discussions about public policy.

Update: For some reason the original post link was taken private, so I’m reposting to the current version.

February 27, 2017

Real GDP Per Capita and the Standard of Living

Published on 20 Nov 2015

They say what matters most in life are the things money can’t buy.

So far, we’ve been paying attention to a figure that’s intimately linked to the things money can buy. That figure is GDP, both nominal, and real. But before you write off GDP as strictly a measure of wealth, here’s something to think about.

Increases in real GDP per capita also correlate to improvements in those things money can’t buy.

Health. Happiness. Education.

What this means is, as real GDP per capita rises, a country also tends to get related benefits.

As the figure increases, people’s longevity tends to march upward along with it. Citizens tend to be better educated. Over time, growth in real GDP per capita also correlates to an increase in income for the country’s poorest citizens.

But before you think of GDP per capita as a panacea for measuring human progress, here’s a caveat.

GDP per capita, while useful, is not a perfect measure.

For example: GDP per capita is roughly the same in Nigeria, Pakistan, and Honduras. As such, you might think the three countries have about the same standard of living.

But, a much larger portion of Nigeria’s population lives on less than $2/day than the other two countries.

This isn’t a question of income, but of income distribution — a matter GDP per capita can’t fully address.

In a way, real GDP per capita is like a thermometer reading — it gives a quick look at temperature, but it doesn’t tell us everything.It’s far from the end-all, be-all of measuring our state of well-being. Still, it’s worth understanding how GDP per capita correlates to many of the other things we care about: our health, our happiness, and our education.

So join us in this video, as we work to understand how GDP per capita helps us measure a country’s standard of living. As we said: it’s not a perfect measure, but it is a useful one.

February 10, 2017

QotD: “First world problems” used to be just “very rich people’s problems”

… my bathroom book (bathroom books are essays or short stories, because if you have never gotten trapped by a novel someone had forgotten in the bathroom and lost the entire morning as well as all circulation in your legs, I can’t explain it to you) is a Daily Life In Medieval England thing. And most of the time I read something that I’m sure the authors thought was new and exotic and think “Well, heck, it was like that in the village.”

[…]

Which brings us back, through back roads to the main point of this post. I was (being evil) reading some of the entries in the medieval life book to older son (having brought the book out of the bathroom to pontificate) and I said “bah, it was like that for us, too. It wasn’t that bad.” And son said “mom, it sounds horrific.” And I said “that’s because you grew up in a superabundant society, overflowing at both property and entertainment, which is why the problems we suffer from are problems that only affected the very rich in the past” (Crisis of identity, extreme sensitivity to suffering, etc.)

Which is also true. And note kindly, that though we’re overflowing at the seams with material goods, property crimes we still have with us, not counting on anything else.

But for my child this is the normal world and it doesn’t occur to him to think of it as superabundant. He just thinks of the conditions I grew up under (I think it was the “most people only had one change of clothes, including underwear” that got him) as barbaric and horrible.

I’ve long since realized that I grew up somewhere between medieval England and Victorian England. Tudor England feels about as familiar to me as the present day which is why I like visiting now and then.

Sarah A. Hoyt, “Time Zones”, According to Hoyt, 2015-06-23.

January 6, 2017

December 2, 2016

India’s bold experiment in self-inflicted economic wounds

Shikha Dalmia explains why Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi suddenly decided to kneecap his country’s money supply and cause massive economic disruption:

Modi was elected in a landslide on the slogan of “Minimum Government, Maximum Governance.” He promised to end babu raj — the rule of corrupt, petty bureaucrats who torment ordinary citizens for bribes — and radically transform India’s economy. But rather than tackling government corruption, he has declared war on private citizens holding black money in the name of making all Indians pay their fair share.

Tax scofflaw behavior is indeed a problem in India. But it is almost always a result of tax rates that are way higher than what people think their government is worth. The enlightened response would be to lower these rates and improve governance. Instead, Modi is taking his country down what Nobel-winning political economist F.A. Hayek called the road to serfdom, where every failed round of coercive government intervention simply becomes an excuse for even more draconian rounds — exactly what was happening in pre-liberalized India.

[…]

About 600 million poor and uneducated Indians don’t have bank accounts. Roughly 300 million don’t have official identification. It’s not easy to swap their soon-to-be worthless cash, which is a catastrophe given that they live hand to mouth. It is heartbreaking to see these people lined up in long queues outside post offices and banks, missing days and days of work, pleading for funds from the very bureaucrats from whose clutches Modi had promised to release them.

Modi hatched his scheme in complete secrecy, without consulting his own economic advisers or the Parliament, lest rich hoarders catch wind and ditch their cash holdings for gold and other assets. Hence, he could not order enough new money printed in advance. This is a massive problem given that about 90 percent of India’s economic transactions are in cash. People need to be able to get money from their banks to meet basic needs. But the government has imposed strict limits on how much of their own money people can withdraw from their own accounts.

[…]

This is not boldness, but sheer conceit based on the misguided notion that people have to be accountable to the government, rather than vice versa. Over time, it will undermine the already low confidence of Indians in their institutions. If Modi could unilaterally and so suddenly re-engineer the currency used by 1.1 billion people, what will he do next? This is a recipe for capital flight and economic retrenchment.

The fear and uncertainty that Modi’s move will breed will turn India’s economic clock back to the dark times of pre-liberalized India — not usher in the good times (aache din) that Modi had promised.

October 19, 2016

Economics Made the World Great – and Can Make It Even Better

Published on Sep 23, 2016

A lot of doom and gloom types say we’re living in dark times. But they’re wrong.

While there are real problems, the world has never been healthier, wealthier, and happier than it is today. Over a billion people have been lifted from dire poverty in just the past few decades.

What has contributed to this improvement of our well-being? The answer can be found in the evolution of economic and policy ideas.

But we can still do better. How will we solve today’s challenges and what breakthroughs will spark change tomorrow?

October 18, 2016

QotD: “Smart Growth” regulations hurt the poor

In the 1970s, municipalities enacted new rules that were designed to protect farmland and to preserve green space surrounding rapidly growing cities by forbidding private development in those areas. By the late 1990s, this practice evolved into a land-use strategy called “smart growth.” (Here’s a video I did about smart growth.) While some of these initiatives may have preserved green space that can be seen, what is harder to see is the resulting supply restriction and higher cost of housing.

Again, the lower the supply of housing, other things equal, the higher real-estate prices will be. Those who now can’t afford to buy will often rent smaller apartments in less-desirable areas, which typically have less influence on the political process. Locally elected officials tend to be more responsive to the interests of current residents who own property, vote, and pay taxes, and less responsive to renters, who are more likely to be transients and nonvoters. That, in turn, makes it easier to implement policies that use regulation to discriminate against people living on low incomes.

Sandy Ikeda, “Shut Out: How Land-Use Regulations Hurt the Poor”, The Freeman, 2015-02-05.

October 1, 2016

Here’s some fantastic news you’re not seeing in the headlines

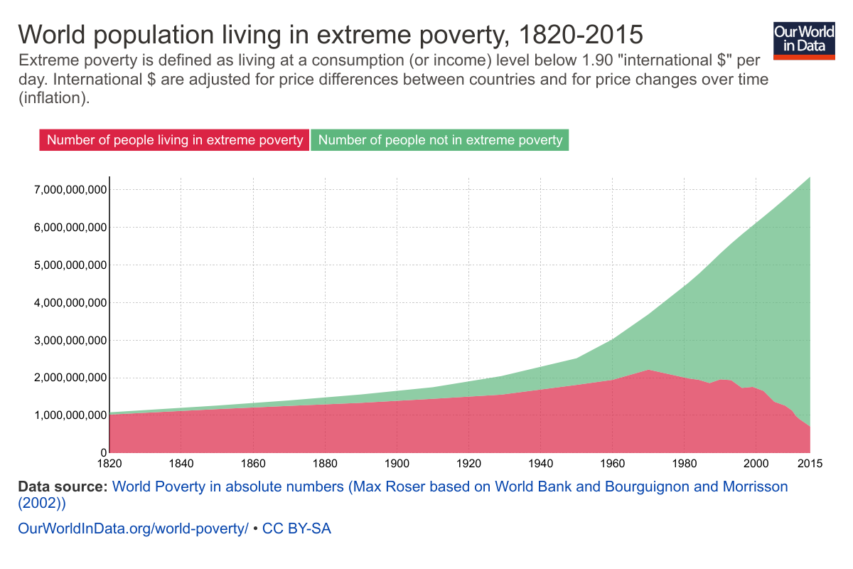

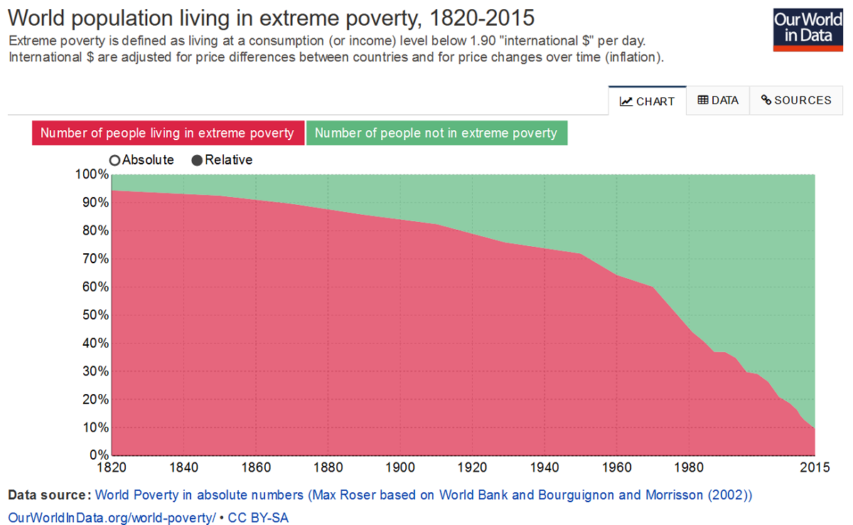

The same world poverty data, presented as absolute or relative levels of poverty:

H/T to Rob Fisher at Samizdata for the link.

September 6, 2016

QotD: Minimum lot size regulations hurt the poor

Other things equal, the larger the lot, the more you’ll pay for it. Regulations that specify minimum lot sizes — that say you can’t build on land smaller than that minimum — increase prices. Regulations that forbid building more units on a given-size lot have the same effect: they restrict supply and make housing more expensive.

People who already live there may only want to preserve their lifestyle. But whether they intend to or not (and many certainly do so intend) the effect of these regulations is to exclude lower-income families. Where do they go? Where they aren’t excluded — usually poorer neighborhoods. But that increases the demand for housing in poorer neighborhoods, where prices will tend to be higher than they would have been.

And it’s not just middle-class families that do this. Very wealthy residents of exclusive neighborhoods and districts also have an incentive to support limits on construction in order to maintain their preferred lifestyle and to keep out the upper-middle-class hoi polloi. Again, the latter then go elsewhere, very often to lower-income neighborhoods — Williamsburg in Brooklyn is a recent example — where they buy more-affordable housing and drive up prices. Those who complain about well-off people moving into poor neighborhoods — a phenomenon known as “gentrification” — may very well have minimum-lot-size and maximum-density regulations to thank.

When government has the authority to restrict building and development, established residents of all income levels will use that power to protect their wealth.

Sandy Ikeda, “Shut Out: How Land-Use Regulations Hurt the Poor”, The Freeman, 2015-02-05.

August 21, 2016

QotD: Price controls and other forms of rationing

Of the numerous and occasionally contradictory techniques used to ration demand and supply [when monetary prices are not used], perhaps the most common is past behavior: persons already in apartments are given preference under rent control, or past acreage determines current allotments under agricultural price support programs. Another common technique is queuing or first come – first served: taxicabs, theater tickets, medical services, and many other goods and services are rationed in this way when their prices are controlled. Of course, discrimination and nepotism are also widely used; the best way to get a rent-controlled apartment is to have a (friendly) relative own a controlled building. Other criteria are productivity – the least productive workers are made unemployed by minimum wage laws;…. collateral – borrowers with little collateral cannot receive legal loans when effective ceilings are placed on interest rates.

Each rationing technique benefits certain groups at the expense of other groups relative to their situation in a free market. Price controls are almost always rationalized, at least in part, as a desire to help the poor, yet it is remarkable how frequently they harm the poor.

Gary Becker, Economic Theory, 1971.

July 15, 2016

QotD: The poverty of the past

I would point you to one of the great economic resources of our times. The work of Angus Maddison. Download that database (it’s a simple Excel file). Play around with it. And then think about it.

While you think about it, ponder the point that Brad Delong likes to make (derived in part from Maddison and also from his own work). The one fact of economics that we need to explain is what the heck happened around 1700? Why did living standards flatline, roughly and around about, from the founding of Ur until someone worked out how to use a steam engine? That’s the one supreme puzzle. Now, we think we’ve found a lot of answers, Malthusian growth giving way to Smithian (and possibly, as Deepak Lal puts it, Promethean). We might want to ascribe it to capitalism, to markets, to the welfare state, to a step change in technology: and bits and pieces of all of those have obviously contributed to where we are now. But something the heck happened which was different from everything that preceded it.

And now back to Maddison’s numbers. To explain them a little bit (and this again draws on points I’ve lifted from Delong). They are in constant dollars. So, an adjustment has been made for inflation over the decades and centuries. We can’t say that sure, peoples’ incomes in the past were low but so were prices. These numbers are at modern prices (actually, the prices of 1992 if I recall correctly, so adjust by 20 odd years mentally). They are also PPP adjusted, another version of the same thing. So they really are (trying, this is more of an art than a science at this distance) trying to reflect different prices in different places as well as the inflation adjustment across time.

Finally, they are of GDP per capita. This isn’t the same as the average income, not at all. Some amount of GDP will flow to capital, there will be inequality of distribution and so on. However, the average living standard of a place and time cannot be more than that GDP per capita. And then look at the numbers again. Up until 1600 or so GDP per capita wandered around between $500 a year and $1,000 a year or so. All over the world. Up a bit, down a bit, the central years of the Roman Empire were better when the Romans were civilising my Celtic forbears than when the Saxons were slaughtering my Celtic forbears but no real breakout from that range.

And remember: this is at 1992 prices. We really are saying that people had the standard of living that we would have if we had $500 or $1,000 a year to go spend in a 1992 Walmart. Now go look at 1890s America. That house on the prairies time. We really are saying that the average American in 1890 (less than in fact, that difference between incomes and GDP, distributional effects) was living on $3,900 a year. And no, not at some different price level. All housing, clothing, heating, food, everything, at the prices that we would see in a 1992 Walmart.

That’s poor.

In the year of my birth it was $12,200: better, certainly, but simply nowhere near as good as today.

It really is important to understand this point. The past was unimaginably poor by our current standards. As are parts of ther world today. Or, as the man said, the Good Old Days are right now.

Tim Worstall, “Joni Ernst, Bread Bags And The Poverty Of The Past”, Forbes, 2015-02-02.

June 27, 2016

May 24, 2016

The Great Enrichment

In the Wall Street Journal, economist Deirdre McCloskey pinpoints the launch point of the greatest increase in global human wealth ever seen:

In the 18th century, liberal thinkers such as Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin courageously advocated liberty in trade. By the 1830s and 1840s, a much enlarged intelligentsia, mostly the sons of bourgeois fathers, commenced sneering loftily at the liberties that had enriched their elders and made possible their own leisure. The sons advocated the vigorous use of the state’s monopoly of violence to achieve one or another utopia, soon.

Intellectuals on the political right, for instance, looked back with nostalgia to an imagined Middle Ages, free from the vulgarity of trade, a nonmarket golden age in which rents and hierarchy ruled. Such a conservative and Romantic vision of olden times fit well with the right’s perch in the ruling class. Later in the 19th century, under the influence of a version of science, the right seized upon social Darwinism and eugenics to devalue the liberty and dignity of ordinary people and to elevate the nation’s mission above the mere individual person, recommending colonialism and compulsory sterilization and the cleansing power of war.

On the left, meanwhile, a different cadre of intellectuals developed the illiberal idea that ideas don’t matter. What matters to progress, the left declared, was the unstoppable tide of history, aided by protest or strike or revolution directed at the evil bourgeoisie — such thrilling actions to be led, naturally, by themselves. Later, in European socialism and American Progressivism, the left proposed to defeat bourgeois monopolies in meat and sugar and steel by gathering under regulation or syndicalism or central planning or collectivization all the monopolies into one supreme monopoly called the state.

While all this deep thinking was roiling the intelligentsia of Europe, the commercial bourgeoisie — despised by the right and the left, and by many in the middle, too — created the Great Enrichment and the modern world. The Enrichment gigantically improved our lives. In doing so, it proved that both social Darwinism and economic Marxism were mistaken. The supposedly inferior races and classes and ethnicities proved not to be so. The exploited proletariat was not driven into misery; it was enriched. It turned out that ordinary men and women didn’t need to be directed from above, and when honored and left alone, became immensely creative.

The Great Enrichment is the most important secular event since human beings first domesticated wheat and horses. It has been and will continue to be more important historically than the rise and fall of empires or the class struggle in all hitherto existing societies. Empire did not enrich Britain. America’s success did not depend on slavery. Power did not lead to plenty, and exploitation was not plenty’s engine. Progress toward French-style equality of outcome was achieved not by taxation and redistribution but by the Scots’ very different notion of equality. The real engine was the expanding ideology of classical liberalism.

The Great Enrichment has restarted history. It will end poverty. For a good part of humankind, it already has. China and India, which have adopted some of economic liberalism, have exploded in growth. Brazil, Russia and South Africa, not to speak of the European Union — all of them fond of planning and protectionism and level playing fields — have stagnated.