The problem with wine is that it’s all so strong these days. I had a Saint-Estèphe last year that was 15 per cent. 15 percent Bordeaux! I used to enjoy having Châteauneuf-du-Pape on Christmas day, but that can touch 16 per cent. So once again Germany is your friend here.

A nice spätburgunder, the delightful German word for pinot noir, would be a good alternative. Or perhaps an English red. They’re not easy to find or cheap but I can thoroughly recommend the 2020 pinot noirs from Gusbourne in Kent and Danbury Ridge in Essex.

With the turkey, keep the pork accessories to a minimum. Don’t sneak into the kitchen to polish off the pigs in blankets. Instead have lots of vegetables, but do not have seconds, no matter how tempting that might be. As for Christmas pudding, avoid, avoid, avoid. Maybe a crumb for appearances’ sake. But you must resist the sweet wine. I’m a sucker for a nice monbazillac but I’ve decided you don’t need port and sweet wine, and I’m going for the port. Eyes on the prize and all that.

The strategy is to reach the port and stilton course having consumed no more than the equivalent of one bottle of wine. Ideally less. If you’ve had two, that’s too much. Go for a walk.

Assuming you’ve reached this stage soberish and with a stomach that’s not rebelling, that doesn’t mean that you can suddenly channel your inner Georgian squire when the decanter comes round. Don’t be like John Mytton, one time MP for Shrewsbury, who arrived at Cambridge University with 2,000 bottles of port: unsurprisingly he didn’t graduate. He was notorious for drunken antics such as setting fire to his nightshirt in a bid to cure hiccups and once rode a bear into a dinner party for a jape. We’ve all had that urge after too much port.

It might seem heretical, but you don’t need to finish off the decanter at the table. A vintage port should be good for four or five days, whereas tawny lasts for weeks, so you can keep coming back to it. If there are only a few port fans in the family, it’s worth opening a bottle on Christmas Eve and having a glass or two. Then if you do decide to polish it off while outlining your plan for getting the British economy back on track, there won’t be quite so much in the bottle. Oh, and tiny glasses, please. Think Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany in Master and Commander.

When lunch is over, say no to coffee and find somewhere to have a nap until it’s time for a cup of tea. Try to avoid eating or drinking alcohol again for the rest of the day. But who am I kidding, I’ll probably open a bottle of Beaujolais to go with my turkey sandwich. And maybe a little port and Stilton. But nothing after nine o’clock. That is very important.

And so to bed for a good night’s sleep and awake rested, if not quite refreshed, and without an angry wife glaring at me. That’s the plan anyway.

Henry Jeffreys, “How to drink port without the storm”, The Critic, 2022-12-09.

December 24, 2025

QotD: Moderation for the inveterate port fan at Christmas

December 20, 2025

The “pursuit” of the Brown University shooter as a parable of incompetence

Mark Steyn is supremely unimpressed with the quality of police work demonstrated by the “forty-seven genius law-enforcement agencies” apparently involved in investigating the murders at Brown University and the murder of an MIT nuclear fusion expert:

The Brown University shooter has been found dead by his own hand in a storage locker in southern New Hampshire. The entire officialdom of Providence, Rhode Island celebrated by throwing “the most worthless, uninformative, cover-your-ass press conference I have ever seen in my entire life“.

You’ll be glad to hear that the DEI Mayor of Providence has declared “we believe that you remain safe in our community“. He said this at 11pm last Sunday, but his statement was technically true because at that point the shooter was driving out of “our community” up to someone else’s community to kill an MIT professor, who would assuredly be alive today had not everybody in Providence bungled everything that could be bungled. The storage-locker guy and the Boston guy are both Portuguese nationals of the same age who are believed by the FBI to have attended the same university in Lisbon at the end of the last century. What that means, who knows? A random mass-shooting as prelude to something more personal and targeted? As is now traditional, I doubt we shall ever know, […] However, we do know how the forty-seven genius law-enforcement agencies “cracked the case”. An Internet user saw this post on Reddit, and brought it to the attention of one of the forty-seven agencies, who shortly thereafter swung into what passes for action. Here’s what the Redditor wrote:

I’m being dead serious. The police need to look into a grey Nissan with Florida plates, possibly a rental. That was the car he was driving. It was parked in front of the little shack behind the Rhode Island Historical Society on the Cooke St side. I know because he used his key fob to open the car, approached it and then something prompted him to back away. When he backed away he relocked the car. I found that odd so when he circled the block I approached the car and that is when I saw the Florida plates. He was parked in the section between the gate of the RIHS and the corner of Cooke and George St.

That’s it. That’s the entire “investigation”. “He blew this case right open. He blew it open,” cooed the Rhode Island Attorney-General, Peter Neronha. “That person led us to the car, which led us to the name, which led us to the photographs of that individual renting the car, which matched the clothing of our shooter here in Providence, that matched the satchel which we see here in Providence.”

Great. His name is “John”, and he had multiple interactions with the killer on the day of the shooting — both in the bathroom of the building two hours beforehand and by the car to which the killer kept circling back to see if “John” had ended his apparent stakeout of the vehicle. He spoke to the man long enough to determine that he had an “Hispanic” accent. In fact, Portuguese. But close enough. Or closer than the forty-seven kick-ass agencies.

But here’s the thing: “John” only wrote his post on Reddit because nobody on the scene was interested in what he’d seen that day. “John” is apparently a homeless man who lives in the basement below the scene of the shooting.

Come again? Brown University lets the homeless live in its faculty buildings? You might want to bear that in mind if you’re thinking of taking on six-figure debt to be gunned down at the Ivy League.

Oh, wait, no, relax: “John” is not any old homeless man but a graduate of Brown. They’re not all working as baristas. So it’s some grandfathered-in alumni legacy racket.

Which brings us to the other thing: He was generally known to be living there. So, on Saturday or at the very latest Sunday, why did no-one from the forty-seven kick-ass agencies seek to interview him? His would surely have been a unique perspective: neither teacher nor pupil, but someone who knows the building after-hours and observes the comings and goings. One expects the three-mil-a-year DEI president’s “campus security” to totally suck, but how can you call in the FBI and then the elite best-of-the-best G-men not be aware that there’s a guy living in the basement under the scene of the crime who had multiple interactions with the perp?

As I have had cause to remark a thousand times, nothing works anymore. When I observe that of the UK, English readers get mildly peeved. When I observe it of the Fifth Republic, French readers start gabbling and waving their Gauloise-stained hands around so animatedly their strings of onions fall from their shoulders. And, when I observe it of the United States, American readers get particularly chippy. But I’m an equal-opportunity civilisational doom-monger: we’re all going over the falls, and arguing that the canoe of the Euro-pussies or the tight-assed Brits is a foot-and-a-half ahead isn’t really much consolation. Police-wise, the Aussie constabulary bollocksed Bondi Beach and the forty-seven Yank agencies bollocksed Brown and MIT.

Of course, with the revelation that the shooter may have been Portuguese, the race hustlers are busy re-sorting the hierarchies of victimhood:

February 23, 2025

Portuguese Navy Lugers: Model m/910 from DWM and Mauser

Forgotten Weapons

Published 2 Nov 2024Following Portuguese Army adoption in 1908, the Portuguese Navy adopted the Luger in 1909 as the m/910. The pattern they chose was a “new model” Luger in 9x19mm, with a 100mm / 4″ barrel. A total of 650 were ordered in late 1909 and delivered between 1910 and 1912. The guns had Portuguese-language safety and extractor markings (“Seguranca” and “Carregada“) and included grip safeties. They were in a dedicated serial number range of 1 to 650. The first 350 were delivered under the reign of Portuguese King Manuel II and had crown-over-anchor chamber crests. With the establishment of a Republic in Portugal, that marking was changed to “R.P.” over an anchor, which was used on the remaining guns (351-650).

In the mid 1930s, the Navy ordered another 156 m/910 Luger pistols, this time from the Mauser company. These had the same Portuguese markings, but without any special crest — just blank chambers. They were numbered in Mauser’s export/commercial serial number range, and are in the “v” block of numbers. A few more very small orders were placed in 1941 and 1942, but these were filled with basically straight German P08 pistols.

(more…)

January 23, 2025

The Google of the early modern era

Ted Gioia compares the modern market power of the Google behemoth to the only commercial enterprise in human history to control half of the world’s trade — Britain’s “John Company”, or formally, the East India Company which lasted over 250 years growing from an also-ran to Dutch and Portuguese EICs to the biggest ever to sail the seas:

No business ever matched the power of the East India Company. It dominated global trade routes, and used that power to control entire nations. Yet it eventually collapsed — ruined by the consequences of its own extreme ambitions.

Anybody who wants to understand how big businesses destroy themselves through greed and overreaching needs to know this case study. And that’s especially true right now — because huge web platforms are trying to do the exact same thing in the digital economy that the East India Company did in the real world.

Google is the closest thing I’ve ever seen to the East India Company. And it will encounter the exact same problems, and perhaps meet the same fate.

The concept is simple. If you control how people connect to the economy, you have enormous power over them.

You don’t even need to run factories or set up retail stores. You don’t need to manufacture anything, or create any object with intrinsic value.

You just control the links between buyers and sellers — and then you squeeze them as hard as you can.

That’s why the East India Company focused on trade routes. They were the hyperlinks of that era.

So it needed ships the way Google needs servers.

The seeds for this rapacious business were planted when the British captured a huge Portuguese ship in 1592. The boat, called the Madre de Deus, was three times larger than anything the Brits had ever built.

But it was NOT a military vessel. The Portuguese ship was filled with cargo.

The sailors couldn’t believe what they had captured. They found chests of gold and silver coins, diamond-set jewelry, pearls as big as your thumb, all sorts of silks and tapestries, and 15 tons of ebony.

The spices alone weighed a staggering 50 tons — cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, pepper, and other magical substances rarely seen in British kitchens.

This one cargo ship represented as much wealth as half of the entire English treasury.

And it raised an obvious question. Why should the English worry about military ships — or anything else, really — when you could make so much money trading all this stuff?

Not long after, a group of merchants and explorers started hatching plans to launch a trading company — and finally received a charter from Queen Elizabeth in 1600.

The East India Company was now a reality, but it needed to play catchup. The Dutch and the Portuguese were already established in the merchant shipping business.

By 1603, the East India Company had three ships. A decade later that had grown to eight. But the bigger it got, the more ambitious it became.

The rates of return were enormous — an average of 138% on the first dozen voyages. So the management was obsessed with expanding as rapidly as possible.

They call it scalability nowadays.

But even if they dominated and oppressed like bullies, these corporate bosses still craved a veneer of respectability and legitimacy — just like Google’s CEO at the innauguration yesterday. So the company got a Coat of Arms, playacting as if it were a royal family or noble clan.

As a royally chartered company, I believe the EIC was automatically entitled to create and use a coat of arms. Here’s the original from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I:

December 21, 2024

QotD: Portugal’s early expansion in the Indian Ocean

At a cursory glance, the first arrival of Portuguese ships in India must not have appeared to be a particularly fateful development. Vasco da Gama’s 1497 expedition to India, which circumnavigated Africa and arrived on the Malabar Coast near Calicut consisted of a mere four ships and 170 men — hardly the sort of force that could obviously threaten to upset the balance of power among the vast and populous states rimming the Indian ocean. The rapid proliferation of Portuguese power in India must have therefore been all the more shocking for the region’s denizens.

The collision of the Iberian and Indian worlds, which possessed diplomatic and religious norms that were mutually unintelligible, was therefore bound to devolve quickly into frustration and eventually violence. The Portuguese, who harbored hopes that India might be home to Christian populations with whom they could link up, were greatly disappointed to discover only Muslims and Hindu “idolaters”. The broader problem, however, was that the market in the Malabar coast was already heavily saturated with Arab merchants who plied the trade routes from India to Egypt — indeed, these were precisely the middle men whom the Portuguese were hoping to outflank.

The particular flashpoint which led to conflict, therefore, were the mutual efforts of the Portuguese and the Arabs to exclude each other from the market, and the devolution to violence was rapid. A second Portuguese expedition, which arrived in 1500 with 13 ships, got the action started by seizing and looting an Arab cargo ship off Calicut; Arab merchants in the city responded by whipping up a mob which massacred some 70 Portuguese in the onshore trading post in full sight of the fleet. The Portuguese, incensed and out for revenge, retaliated in turn by bombarding Calicut from the sea; their powerful cannon killed hundreds and left much of the town (which was not fortified) in ruins. They then seized the cargo of some 10 Arab vessels along the coast and hauled out for home.

The 1500 expedition unveiled an emerging pattern and basis for Portugal’s emerging India project. The voyage was marked by significant frustration: in addition to the massacre of the shore party in Calicut, there were significant losses to shipwreck and scurvy, and the expedition had failed to achieve its goal of establishing a trading post and stable relations in Calicut. Even so, the returns — mainly spices looted from Arab merchant vessels — were more than sufficient to justify the expense of more ships, more men, and more voyages. On the shore, the Portuguese felt the acute vulnerability of their tiny numbers, having been overwhelmed and massacred by a mob of civilians, but the power of their cannon fire and the superiority of their seamanship gave them a powerful kinetic tool.

Big Serge, “The Rise of Shot and Sail”, Big Serge Thought, 2024-09-13.

October 13, 2024

QotD: Portugal as “ADHD with borders”

… I often refer to Portugal as ADHD with borders. And it is that. It’s weird, the level of ADD that’s considered completely normal there. (And I was off the charts even for there. Oh, well.) But it took me till this last visit, when I’m almost — to the extent I’m fully acculturated here, or as much as it’s possible to be — to realize how much of Portugal’s inability to organize its way out of a wet paper bag OR maintain anything less durable than a Roman aqueduct (and even those!) is reinforced and driven to eleventy by a culture that goes “The highest virtue is doing things fast, no matter how BADLY they’re done”. And that’s pushed everywhere and by every possible means. And yes, I grew up with it (Anyone making a comment about my books gets put in the corner. Actually they’re worse if I take very long. Yes, I have an explanation, but it doesn’t matter. It is what it is) and internalized it to such an extent it took almost forty years to SEE it was there and it was bad.

Sarah Hoyt, “Culture Clash”, According to Hoyt, 2024-07-09.

October 11, 2024

QotD: Fascists are inherently bad at war

For this week’s musing, I wanted to take the opportunity to expand a bit on a topic that I raised on Twitter which draw a fair bit of commentary: that fascists and fascist governments, despite their positioning are generally bad at war. And let me note at the outset, I am using fascist fairly narrowly – I generally follow Umberto Eco’s definition (from “Ur Fascism” (1995)). Consequently, not all authoritarian or even right-authoritarian governments are fascist (but many are). Fascist has to mean something more specific than “people I disagree with” to be a useful term (mostly, of course, useful as a warning).

First, I want to explain why I think this is a point worth making. For the most part, when we critique fascism (and other authoritarian ideologies), we focus on the inability of these ideologies to deliver on the things we – the (I hope) non-fascists – value, like liberty, prosperity, stability and peace. The problem is that the folks who might be beguiled by authoritarian ideologies are at risk precisely because they do not value those things – or at least, do not realize how much they value those things and won’t until they are gone. That is, of course, its own moral failing, but society as a whole benefits from having fewer fascists, so the exercise of deflating the appeal of fascism retains value for our sake, rather than for the sake of the would-be fascists (though they benefit as well, as it is, in fact, bad for you to be a fascist).

But war, war is something fascists value intensely because the beating heart of fascist ideology is a desire to prove heroic masculinity in the crucible of violent conflict (arising out of deep insecurity, generally). Or as Eco puts it, “For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life, but, rather, life is lived for struggle … life is permanent warfare” and as a result, “everyone is educated to become a hero“. Being good at war is fundamentally central to fascism in nearly all of its forms – indeed, I’d argue nothing is so central. Consequently, there is real value in showing that fascism is, in fact, bad at war, which it is.

Now how do we assess if a state is “good” at war? The great temptation here is to look at inputs: who has the best equipment, the “best” soldiers (good luck assessing that), the most “strategic geniuses” and so on. But war is not a baseball game. No one cares about your RBI or On-Base percentage. If a country’s soldiers fight marvelously in a way that guarantees the destruction of their state and the total annihilation of their people, no one will sing their praises – indeed, no one will be left alive to do so.

Instead, war is an activity judged purely on outcomes, by which we mean strategic outcomes. Being “good at war” means securing desired strategic outcomes or at least avoiding undesirable ones. There is, after all, something to be said for a country which manages to salvage a draw from a disadvantageous war (especially one it did not start) rather than total defeat, just as much as a country that conquers. Meanwhile, failure in wars of choice – that is, wars a state starts which it could have equally chosen not to start – are more damning than failures in wars of necessity. And the most fundamental strategic objective of every state or polity is to survive, so the failure to ensure that basic outcome is a severe failure indeed.

Judged by that metric, fascist governments are terrible at war. There haven’t been all that many fascist governments, historically speaking and a shocking percentage of them started wars of choice which resulted in the absolute destruction of their regime and state, the worst possible strategic outcome. Most long-standing states have been to war many times, winning sometimes and losing sometimes, but generally able to preserve the existence of their state even in defeat. At this basic task, however, fascist states usually fail.

The rejoinder to this is to argue that, “well, yes, but they were outnumbered, they were outproduced, they were ganged up on” – in the most absurd example, folks quite literally argued that the Nazis at least had a positive k:d (kill-to-death ratio) like this was a game of Call of Duty. But war is not a game – no one cares what your KDA is if you lose and your state is extinguished. All that matters is strategic outcomes: war is fought for no other purpose because war is an extension of policy (drink!). Creating situations – and fascist governments regularly created such situations. Starting a war in which you will be outnumbered, ganged up on, outproduced and then smashed flat: that is being bad at war.

Countries, governments and ideologies which are good at war do not voluntarily start unwinnable wars.

So how do fascist governments do at war? Terribly. The two most clear-cut examples of fascist governments, the ones most everyone agrees on, are of course Mussolini’s fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Fascist Italy started a number of colonial wars, most notably the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which it won, but at ruinous cost, leading it to fall into a decidedly junior position behind Germany. Mussolini then opted by choice to join WWII, leading to the destruction of his regime, his state, its monarchy and the loss of his life; he managed to destroy Italy in just 22 years. This is, by the standards of regimes, abjectly terrible.

Nazi Germany’s record manages to somehow be worse. Hitler comes to power in 1933, precipitates WWII (in Europe) in 1939 and leads his country to annihilation by 1945, just 12 years. In short, Nazi Germany fought one war, which it lost as thoroughly and completely as it is possible to lose; in a sense the Nazis are necessarily tied for the position of “worst regime at war in history” by virtue of having never won a war, nor survived a war, nor avoided a war. Hitler’s decision, while fighting a great power with nearly as large a resource base as his own (Britain) to voluntarily declare war on not one (USSR) but two (USA) much larger and in the event stronger powers is an act of staggeringly bad strategic mismanagement. The Nazis also mismanaged their war economy, designed finicky, bespoke equipment ill-suited for the war they were waging and ran down their armies so hard that they effectively demodernized them inside of Russia. It is absolutely the case that the liberal democracies were unprepared for 1940, but it is also the case that Hitler inflicted upon his own people – not including his many, horrible domestic crimes – far more damage than he meted out even to conquered France.

Beyond these two, the next most “clearly fascist” government is generally Francisco Franco’s Spain – a clearly right-authoritarian regime, but there is some argument as to if we should understand them as fascist. Francoist Spain may have one of the best war records of any fascist state, on account of generally avoiding foreign wars: the Falangists win the Spanish Civil War, win a military victory in a small war against Morocco in 1957-8 (started by Moroccan insurgents) which nevertheless sees Spanish territory shrink (so a military victory but a strategic defeat), rather than expand, and then steadily relinquish most of their remaining imperial holdings. It turns out that the best “good at war” fascist state is the one that avoids starting wars and so limits the wars it can possibly lose.

Broader definitions of fascism than this will scoop up other right-authoritarian governments (and start no end of arguments) but the candidates for fascist or near-fascist regimes that have been militarily successful are few. Salazar (Portugal) avoided aggressive wars but his government lost its wars to retain a hold on Portugal’s overseas empire. Imperial Japan’s ideology has its own features and so may not be classified as fascist, but hardly helps the war record if included. Perón (Argentina) is sometimes described as near-fascist, but also avoided foreign wars. I’ve seen the Baathist regimes (Assad’s Syria and Hussein’s Iraq) described as effectively fascist with cosmetic socialist trappings and the military record there is awful: Saddam Hussein’s Iraq started a war of choice with Iran where it barely managed to salvage a brutal draw, before getting blown out twice by the United States (the first time as a result of a war of choice, invading Kuwait!), with the second instance causing the end of the regime. Syria, of course, lost a war of choice against Israel in 1967, then was crushed by Israel again in another war of choice in 1973, then found itself unable to control even its own country during the Syrian Civil War (2011-present), with significant parts of Syria still outside of regime control as of early 2024.

And of course there are those who would argue that Putin’s Russia today is effectively fascist (“Rashist”) and one can hardly be impressed by the Russian army managing – barely, at times – to hold its own in another war of choice against a country a fourth its size in population, with a tenth of the economy which was itself not well prepared for a war that Russia had spent a decade rearming and planning for. Russia may yet salvage some sort of ugly draw out of this war – more a result of western, especially American, political dysfunction than Russian military effectiveness – but the original strategic objectives of effectively conquering Ukraine seem profoundly out of reach while the damage to Russia’s military and broader strategic interests is considerable.

I imagine I am missing other near-fascist regimes, but as far as I can tell, the closest a fascist regime gets to being effective at achieving desired strategic outcomes in non-civil wars is the time Italy defeated Ethiopia but at such great cost that in the short-term they could no longer stop Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria and in the long-term effectively became a vassal state of Hitler’s Germany. Instead, the more standard pattern is that fascist or near-fascist regimes regularly start wars of choice which they then lose catastrophically. That is about as bad at war as one can be.

We miss this fact precisely because fascism prioritizes so heavily all of the signifiers of military strength, the pageantry rather than the reality and that pageantry beguiles people. Because being good at war is so central to fascist ideology, fascist governments lie about, set up grand parades of their armies, create propaganda videos about how amazing their armies are. Meanwhile other kinds of governments – liberal democracies, but also traditional monarchies and oligarchies – are often less concerned with the appearance of military strength than the reality of it, and so are more willing to engage in potentially embarrassing self-study and soul-searching. Meanwhile, unencumbered by fascism’s nationalist or racist ideological blinders, they are also often better at making grounded strategic assessments of their power and ability to achieve objectives, while the fascists are so focused on projecting a sense of strength (to make up for their crippling insecurities).

The resulting poor military performance should not be a surprise. Fascist governments, as Eco notes, “are condemned to lose wars because they are constitutionally incapable of objectively evaluating the force of the enemy”. Fascism’s cult of machismo also tends to be a poor fit for modern, industrialized and mechanized war, while fascism’s disdain for the intellectual is a poor fit for sound strategic thinking. Put bluntly, fascism is a loser’s ideology, a smothering emotional safety blanket for deeply insecure and broken people (mostly men), which only makes their problems worse until it destroys them and everyone around them.

This is, however, not an invitation to complacency for liberal democracies which – contrary to fascism – have tended to be quite good at war (though that hardly means they always win). One thing the Second World War clearly demonstrated was that as militarily incompetent as they tend to be, fascist governments can defeat liberal democracies if the liberal democracies are unprepared and politically divided. The War in Ukraine may yet demonstrate the same thing, for Ukraine was unprepared in 2022 and Ukraine’s friends are sadly politically divided now. Instead, it should be a reminder that fascist and near-fascist regimes have a habit of launching stupid wars and so any free country with such a neighbor must be on doubly on guard.

But it should also be a reminder that, although fascists and near-fascists promise to restore manly, masculine military might, they have never, ever actually succeeded in doing that, instead racking up an embarrassing record of military disappointments (and terrible, horrible crimes, lest we forget). Fascism – and indeed, authoritarianisms of all kinds – are ideologies which fail to deliver the things a wise, sane people love – liberty, prosperity, stability and peace – but they also fail to deliver the things they promise.

These are loser ideologies. For losers. Like a drunk fumbling with a loaded pistol, they would be humiliatingly comical if they weren’t also dangerous. And they’re bad at war.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, February 23, 2024 (On the Military Failures of Fascism)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-02-23.

July 26, 2024

QotD: Comparative advantage

To produce wine in Portugal, might require only the labour of 80 men for one year, and to produce the cloth in the same country, might require the labour of 90 men for the same time. It would therefore be advantageous for her to export wine in exchange for cloth. This exchange might even take place, notwithstanding that the commodity imported by Portugal could be produced there with less labour than in England. Though she could make the cloth with the labour of 90 men, she would import it from a country where it required the labour of 100 men to produce it, because it would be advantageous to her rather to employ her capital in the production of wine, for which she would obtain more cloth from England, than she could produce by diverting a portion of her capital from the cultivation of vines to the manufacture of cloth.

David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), quoted on the Library of Economics and Liberty site.

January 28, 2024

Adolescence is “a profoundly unnatural life-stage”

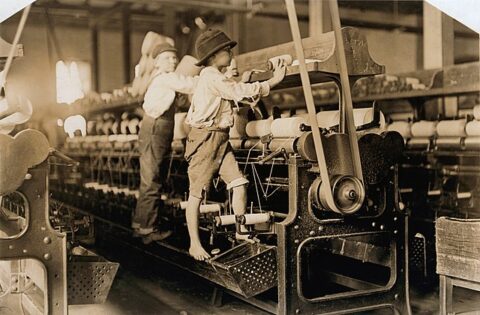

Sarah Hoyt on the plight of the younger Millennials and the Gen Z kids in our over-supervised safety-at-all-costs culture today:

Child labour laws did generally get younger children out of dangerous places like mines, mills, and factories. Modern child labour laws instead keep young adults from gaining work experience in many cases.

Photo of pre-teen children working in a mill in Macon, Georgia in 1909. Photo NCLC.01581, Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons.

Mostly, it gets attributed to “kids these days” but unless you have kids, these days, you don’t know how they are bound. And even if you do, you might not realize it, because all you see is the infantilization of a generation, and not that they, themselves, aren’t the ones doing the infantilizing, but all those “good rules” and regulations and laws are doing it.

I realized about 10 years ago that my son’s generation was about 10 years behind where we were. In their mid twenties they were doing things we did in our teens. It was disconcerting. And even I had no idea why, other than too much regimentation in school, too much of a never end of button counting, and not enough room or freedom to think or be on their own.

Since then … I’ve seen more. And a lot of the reason they are younger than we were is that the entire world is geared not to let them grow up. I mean, let’s be glad that — unprepared or not — they’re legal adults at 18, or people would be denouncing them for walking alone down the street, without an “adult” at 25.

There’s also … adolescence is in some ways a profoundly unnatural life-stage, and more or less invented in the 20th century. In the past, sure, people were children, and people grew to be adults, but there wasn’t this protracted time period where they were adults in size and at least some ability, but weren’t allowed to be adults: they weren’t allowed to earn or spend, or make their own decisions, for years.

The earn or spend thing is important. Kids used to grow along with their tasks. Read Tudor or colonial memoirs, and you find four year olds looking after cows or horses, or learning Latin, or other unlikely things even for twelve year olds in our time.

Mom went to work at 10 and started getting a salary. It wasn’t much, and 90% of it went to her parents’ budget. But she was working, holding down a job, doing things that were maybe not at adult level, but could lead to it, eventually, if she applied herself. This was normal for her generation. In my own generation, amid the working class, most people went to work at 10. Heck, amid the middle class, most people went to work at 15 or so, after 9th grade. Were they more mature than the rest of us that went all the way to college?

I wouldn’t have thought that at the time, but yes, of course they were. Most of my elementary school classmates were married, with kids by the time my biggest worries were final exams. Of course, with my intellectual pride I looked down on them but now I understand they were managing a very difficult job, which at the time I could not have done.

I always feel stunned and shocked when someone says the kids should be “holding down two jobs like I was at 16” or “working to pay their way through college”. (That last is a giggle as it has two impossibilities. Finding a job that pays enough after college which has a lot of make-work expectations, and making a full-time middle-class salary, which is what college costs these days.) Two Jobs. At 16. The difficulties in giving work to 16 year olds, increasingly restriction of hours, etc. combined with chaotic scheduling in the only unskilled jobs remaining (mostly just retail) means that until recently none of them could find A job. Let alone two. And the recently was during Covid. I haven’t seen so many little 16 year olds cashiering, or serving at tables recently. And that’s because most people I’m seeing are around my age: I guess unemployment is biting hard.

But you know, all these strong rules against “child labor” mean that most kids hit 18 or, if they’re going to college, 22 or — more likely, as most degrees (remember make work?) are taking 6 or 7 years — 24, with absolutely no job experience. Which means their applications aren’t even looked at. Not seriously.

Honestly, almost every young person — particularly young men — I know who found a job, and is doing relatively well, did so through contacts. Through friends of friends. Through knowing someone.

This is a bad sign, because it’s how Portugal functions, and it is not in any way shape or form meritocracy, which in turn contributes to other things falling apart.

But more and more what I’m seeing is young people hitting their mid twenties lost, and doing this, and doing that, and trying this and trying that, and nothing ever gels. To make things worse, they don’t have the habits mom had by 10, because they haven’t been allowed to acquire them.

There was a similar generation — one, while here we’re well into two — in Portugal, where unemployment was so bad (the generation before mine) that most people weren’t “established” on a path till their mid thirties. I’d guess about half of them never got the knack of it: of the day to day of working, fulfilling the work duties, just … the unglamorous day to day that makes us adults.

June 15, 2023

Sarah Hoyt objects to being an “imaginary creature”

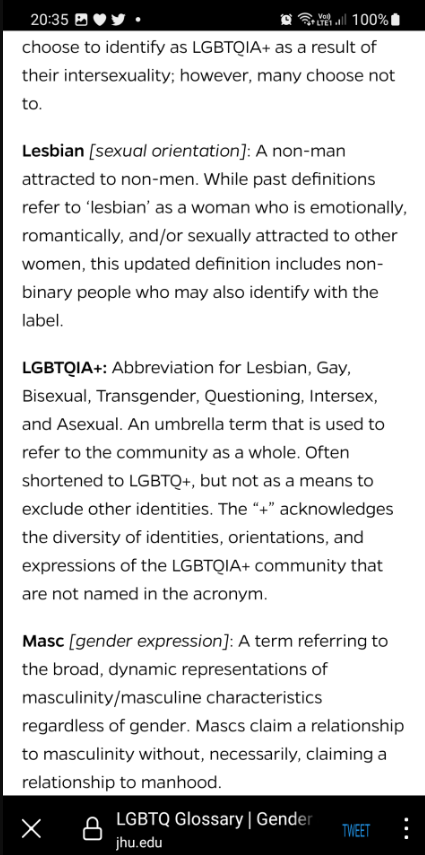

Recent revisions to the quasi-official dictionary of the woke English language seem to have classified individuals like Sarah as “non-men”:

I was born female in a country that was profoundly patriarchal and, back then, patriarchal without guilt. So, it was acceptable to make jokes about women being dumber than men. And it was acceptable for teachers to assume you were dumb because female.

Most of these things amused me. It was always fun in mixed classes after the first test to watch the teacher look at my test and at the boys in the class trying to figure out what parent was so cruel as to name their son a girl’s name.

I enjoyed breaking people’s minds. And once I was known in a group or place, I was not treated as inferior. The only things that truly annoyed me were the ones I thought were arbitrary restrictions, like not going out after 8 pm alone. Took flaunting them a few times to find out they weren’t arbitrary. Or rather, they were arbitrary but since culture-wide flaunting was dangerous, and I was lucky not to pay for the flaunting with life or limb.

Yes, I went through a phase of screaming that I was just as good as any man. Then realized it was true and stopped screaming it.

Then got married and had kids, and realized I was just as good but different. I could do things men couldn’t do. Parenthood is different as a woman. And none of it mattered to my worth, just like being short and having brown hair doesn’t make me inferior to tall blonds. Just different.

And even though I’m a highly atypical woman, at the beginning of my sixth decade, I find myself completely at peace with the fact I am a woman and not apologetic at all for it.

Imagine my surprise when I found out women don’t exist. There’s only man and non-man.

This nonsense, from here, has got to stop. When you get so “inclusive” you’re excluding an entire biological sex (but curiously not the other) you might want to re-evaluate your principles. Also, your sanity.

Yes, I know, saying this makes me a TERF, which is nonsense. Maybe a TERNF, since I’ve not called myself a feminist since I was 18 and realized feminism aimed for making women “win” at men’s expense. It wasn’t aiming for equality but for “equity” and since I never needed a movement to outcompete males, I decided it was spinach and to h*ll with it.

Also I’m not trans-exclusionary. If women don’t exist, what the heck are men who are trans trans TO? Non-man? Uh … what? What are drag queens imitating? Is it just non-man?

April 30, 2023

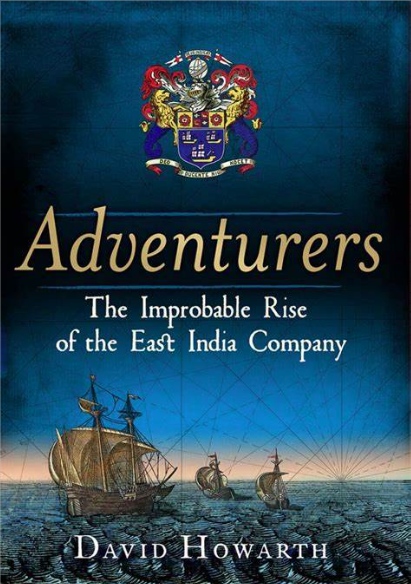

David Howarth’s history of the East India Company

Robert Lyman reviews David Howarth’s recent work Adventurers: The Improbable Rise of the East India Company:

It is the human detail of the EIC and the ultimate triumph of its trading endeavours despite the best efforts of Portugal, the Dutch Republic and of the vicissitudes of Neptune that holds great fascination for me, and which is the triumph of Howarth’s intimate and intricate portrayal of the EIC in the first century of its existence. His great achievement is both to bring the dusty tomes of the Company back to life, not just to humanise one of the greatest trading ventures of all of human history, but to interpret the early years of the Company (his book spans 1600 to 1688, though most of the narrative is pre-1650) as a peculiarly human rather than an institutional endeavour. Is this important? Yes. Humans have agency; institutions consume or act upon the determining agency of human beings, not the other way around. Too much of modern (post 1880) history is based upon determining the perspective of organisations and movements (as interpreted by later historians, many with their own ideological baggage) rather than of actual, real live people making decisions for themselves in the peculiar and particular context of their lives and times.

The means through which Howarth paints his story is by the decisions, actions and activities of actual people, some influential decision-makers and many others who were not, all of which makes up a remarkably vivid tapestry of human intercourse. Each chapter, for instance, is constructed around a person or group of people. One powerfully tells the story of the men of the Peppercorn, an EIC East Indiaman, as it seeks out the riches of a world on the extreme periphery of the consciousness of most Europeans. The ultimate triumph of European expansion into Asia is not difficult to comprehend. Europe was pursuing an adventure, aggressively, relentlessly and determinedly, to bring the riches of the world back to its own shores. At no time did the Chinese, Japanese, Indians or inhabitants of the Spice Islands return the favour. The energetic persistence of Sir Thomas Roe, for instance, the Company’s ambassador to the Mughal court (1615-1619), is easily compared to the intellectual (and alcoholic) indolence of the Great Mughal with whom Roe was attempting to interact. Roe was there, in India: Europeans were interested in the “East” and with travelling to the other side of the world for purposes of human engagement, adventure, patriotism and, yes, greed and selfish self-interest. The Great Mughal, by contrast, was also driven by greed and self-interest, but he just wasn’t interested in exploring. He certainly wasn’t interested in Europe. He was already, in his view, at the top of the human tree and had no need for either the ideas or the money of the red-haired barbarians who came from across the sea, a sea that incidentally few Mughal emperors had (amazingly) ever even seen. Fascinatingly, the Mughal shared with King James I an abhorrence with “trade”, though James knew he needed grubby merchants like Sir John Lyman [the reviewer’s ancestor] as they gave him coin. It wasn’t just about the merchants: Kings and governments needed the money that the merchants delivered by the bucket load because they couldn’t create it themselves. Howarth astutely observes that the “EIC belonged to the globe of politics as much as it did to the sphere of commerce”. Indeed, something of a symbiosis between the two in Tudor and Stewart England created a sense of nationhood – in the face of the resistance of others, in Europe and further afield – for the first time. The Mughal Empire was ultimately swallowed up as a result of a dynamism by European politicians and merchants working in unison which it never bothered to replicate by undergoing the reverse journey.

And power? No. Howarth is remarkably clear that the primary task of the EIC was to make money, not to accrue territory, create power in foreign territories or aggrandise native populations. The role of the executive arm of the EIC (its ships, sailors and factors) was to make money for its investors, many of whom were the very merchant adventurers in the little ships travelling east over vast oceans. The great game of mercantile expansion took place because those who had most to lose were also sailing the ships, negotiating with foreign emissaries, fighting the Portuguese and the Dutch and placing their lives on the line. Amazingly, in 1570 England had only 58,000 tons of marine tonnage compared with Spain’s 300,000, and was very definitely the minnow in the rush to conquer the seas. The men who built and sailed its boats came from a long way behind, and yet in time were to build a seagoing commercial empire which more than rivalled all its competition. Its early growth was fuelled by the wealth provided by spice rather than slaves and, in contradistinction to what some modern historical moralists are keen to tell us, by a “reluctance to use violence and vigilance to avoid land commitments”. Indeed, unlike that of the Dutch, and despite what one might assume if we were to read the British national anthem back into history, “expansion in England happened with no appeal whatever to national glory”.

The amazing thing about the EIC was just how chaotic and disorganised it was. There was nothing inevitable about its rise as a monolithic mercantile overlord destined for instance, in the due course of time, to rule India. Second guessing history is only possible for historians able to look backwards and identify trends and features, convictions that didn’t exist for those when history was happening trying to make their way through the fog of an uncertain and troublesome future. The EIC proved simply to be better organised than the Portuguese, and not distracted as the Dutch were in their long war against Spain. Luck and serendipity played as much a role on the eventual survival of the EIC as did its ability to raise massive amounts of money from venturers in England (every raise or round of financing was heavily over-subscribed) for its adventures and to recruit adventurers to take its ships to sea. The EIC was phenomenally successful in raising voluntary capital to fund its ventures relative to other European states. By comparison, “although Iberian barns might have looked well built and better stocked, once they were given a good kick the rusted hinges flew off”.

February 11, 2023

Americans tend to think other countries are just like America, but with weird accents and quaint clothing

Sarah Hoyt on the common problem Americans (and to a lesser extent, Canadians) have in trying to understand other nations even if they’ve done some international travel:

I also see every country, regardless of their history making the assumption that the modus operandi and motives of other cultures and organizations is exactly the same as theirs. I’ve now mentioned about a million times the idiots who went over as Human Shields to Iraq because “they can’t even provide drinking water for their people, how would they have missiles” thereby completely missing the fact that other countries — dictatorships at that — have different priorities than say the US or England, even. In the same way, Portugal assumes that every country is as fraught as corruption as they are. Which works fine for other Latin countries, but fails them when it comes to other places, because as corrupt as we are … yeah. It’s nowhere near there yet. Russia assumes everyone moves, breathes and thinks only about them, and that everyone’s intention is to threaten them or conquer them, because they are obsessed with their dreams of national glory, and they think they should rule the world. And the US by and large goes around like a large vaguely autistic child who really, really, really doesn’t understand how different it is from other nations, or if it does assumes it’s worse.

Look, it’s part of the reason our intelligence services are so sucky. To completely understand what other countries are doing and why, you have to know they have very different cultures. They’re not you. Most countries can sort of extrapolate other countries, but America is so different we suck at it. This is why we tend to think places like the USSR (Russia’s party mask) were totes super powers. Because for America to do and say the things they did and said, we’d have to be very sure of our power. But other countries aren’t America. So we go through the world acting like gullible giants.

In fact Americans have one of the weirder cultures in the world. It’s just not in your face weird as China (whose history reads like they should be extra-terrestrials.) It’s subtle and more in the mental furniture.

Because of this, and because we’re a continent-sized nation, born and bred Americans (as opposed to imports like me) read not just the rest of the world but history hilariously wrong. (The history part is because at least when I went through school here — one year — American schools suck at teaching history. It’s all names and dates, not “Why did France do that?” Yeah, probably not worse than the rest of the world, now that all the books have just-so Marxist explanations, but still stupid.)

I had friends in my writers’ group back when who were writing, say, ancient Egyptian families and couldn’t understand in most of them the teens wouldn’t be/act the same as American teens now. Heck, my dad’s generation in Portugal, less than 100 years ago weren’t “teens” really. Their equivalent was under ten. Because by 12 most of the boys in the village were apprenticed in the job they’d have for life. (And dad was in school, yes, but it was way tougher than even I had.) They didn’t have time. And even I — and you guys know my basic disposition — didn’t sass my parents as American teens do, because there was a deep “fund” of “respect the elders” in the culture. I still have trouble calling people older than I — even colleagues — by their first name.

And then there’s the hilarious — or sad — misunderstandings like the Human Shields mentioned above. It’s sad, because they will buy other countries at face value, but are willing to entertain their own country might be evil. Which is why we have a large contingent of open-mouth guppies who think that the US invented slavery. Even though places around the world still have slavery. Including China, where everyone is a slave, it’s the degree that varies, of course.

The problem is made worse — not better — by idiotic travel abroad.

To understand the differences in a country, you need to live with them, as one of them, for a while. You need to speak the language well enough you understand overheard conversations. Etc.

My experience coming over as an exchange student for 12th grade was about ideal. I lived with an American family, as one of their kids, and attended a school nowhere USA (okay, a suburb of Akron, Ohio) and yeah, I had slight celebrity status in the school — being one of three foreign exchange students — but not that much. So I got to experience the normal life of normal people in normal circumstances, which was an eye-opener.

I always wanted my kids to follow me in this experience, but you know, things got complicated around the time they were of age to do it. So they didn’t. They still have experienced life as an every day foreigner when we visit my parents. In fact the issue there is that they never get past the irritation “What do you mean we can’t do that” and towards “oh, it’s just different. Still sucky, but different.”

Going over for two weeks, with or without the guided tour, staying in nice hotels and associating only with people at your social level and not past the level of polite interaction does not enlarge the mind. Instead, it gives a false sense of knowing what the world is like. This is where we get the “socialists” who know it’s good, because look at all the magnificent buildings in Europe, and the fact everyone has time to sit in the coffee shop and socialize with friends. And look at all the amazing public transportation. And and and. If you lived there, or knew history, you’d know most of the buildings created by socialists in the 20th and 21st century are already crumbling. (Some start before being finished.) You’d know people sit around in coffee shops either because they are unemployed, they pretend to work and their boss pretends to pay them, or all of the above. And all of it is paid for in a significant reduction in lifestyle and just the general comfort of life. (Take it from me. Their lifestyle is two social economic levels down from us, for the same relative “income level.” So, you know, upper class is middle-middle class here.) And you’d know the frustration of waiting for the bus on a rainy, windy day, getting soaked, but the bus is late because all the bus drivers went out for a pint together. And suddenly there’s five of them in a row, but you’re already soaked and starting to cough. More importantly you’d know the public transport only works because everyone works in the city and lives in crowded suburbs, in stack-a-prole apartments, while the countryside is relatively empty. And the people who live there need to buy gas at ridiculous prices, so they can barely afford it.

Tank Chats #167 | French Panhard EBR | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 28 Oct 2022How much do you know about the Panhard EBR? Join David Willey for this week’s Tank Chat as he covers the development, design and use of this French armoured car.

(more…)

September 3, 2022

Napoleon Defeats Russia: Friedland 1807

Epic History TV

Published 28 Sep 2018Napoleon brings his war against Russia and Prussia to an end with victory at Friedland, leading to the famous Tilsit conference, after which Napoleon stood at the peak of his power.

(more…)

May 31, 2022

QotD: Chaos, the ancient enemy

No, not that one. Though perhaps that one, or a more concrete incarnation of it. Though evil seems cohesive and organized, it is often either about to bring about the oldest enemy of mankind, perhaps the oldest enemy of life or perhaps just that enemy with a mask on, dancing forever formlessly in the void.

I was probably one of the few people not at all surprised that Jordan Peterson’s seminal work was subtitled “An antidote to chaos”. Because of course that is our ancient enemy, the enemy of everything that lives down to the smallest organized cell.

Perhaps it is my Greek ancestry (in culture, via the Romans, if nothing else. I mean 23 and me has opinions, but they revise my genetic makeup so often I’m not betting on anything. Also, frankly, they base it on today’s populations, so that if say every person in an extended family left Greece to colonize Iberia, today I’d show only Iberian genetics. [Spoiler: I don’t. Europeans are far more mixed up than they dream of in their philosophies.]) that makes me see Chaos as a vast force waiting in the darkness before and around this brief bit of light that is Earth and humanity, ready to devour us all.

I can’t be the only one impressed by this image, as I’ve run across echoes of it in countless stories both science fiction and fantasy. If you’re reading the kind of story that tries to scrute the ultimate inscrutable and unscrew the parts of the mental universe of humanity to take a metaphorical look under the hood, sooner or later you come across a scene where the main characters get to the end of it all and face howling chaos and darkness. Only it usually doesn’t even howl, nor is it dark. It’s just nothing. Which is the ultimate face and vision of chaos. And most of us know it. Perhaps writers, most of all.

I have a complex relation with chaos, in that part of me seems to be permanently submerged in it. Some of this is the culture in which I was brought up. You know, the Portuguese might have crime, but no one can accuse them of having organized crime. Or indeed organized much of anything.

It’s not just the disease of “late industrializing culture”. There’s something more at work. For one, the Portuguese pride themselves on it. They routinely contrast the British habit of queuing for everything to the Portuguese habit of queuing for nothing (And you haven’t lived till you see a communion scrum with the little old ladies having their elbows at the level of young men’s crotches) by describing the way Portuguese do not queue as “All in a pile and may G-d help us”.

Sarah Hoyt, “The Ancient Enemy”, According to Hoyt, 2019-04-05.