I am not in fact claiming that medieval Catholicism was mere ritual, but let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that it was — that so long as you bought your indulgences and gave your mite to the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever and showed up and stayed awake every Sunday as the priest blathered incomprehensible Latin at you, your salvation was assured, no matter how big a reprobate you might be in your “private” life. Despite it all, there are two enormous advantages to this system:

First, n.b. that “private” is in quotation marks up there. Medieval men didn’t have private lives as we’d understand them. Indeed, I’ve heard it argued by cultural anthropology types that medieval men didn’t think of themselves as individuals at all, and while I’m in no position to judge all the evidence, it seems to accord with some of the most baffling-to-us aspects of medieval behavior. Consider a world in which a tag like “red-haired John” was sufficient to name a man for all practical purposes, and in which even literate men didn’t spell their own names the same way twice in the same letter. Perhaps this indicates a rock-solid sense of individuality, but I’d argue the opposite — it doesn’t matter what the marks on the paper are, or that there’s another guy named John in the same village with red hair. That person is so enmeshed in the life of his community — family, clan, parish, the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever — that “he” doesn’t really exist without them.

Should he find himself away from his village — maybe he’s the lone survivor of the Black Death — then he’d happily become someone completely different. The new community in which he found himself might start out as “a valley full of solitary cowboys”, as the old Stephen Leacock joke went — they were all lone survivors of the Plague — but pretty soon they’d enmesh themselves into a real community, and red-haired John would cease to be red-haired John. He’d probably literally forget it, because it doesn’t matter — now he’s “John the Blacksmith” or whatever. Since so many of our problems stem from aggressive, indeed overweening, assertions of individuality, a return to public ritual life would go a long way to fixing them.

The second huge advantage, tied to the first, is that community ritual life is objective. Maybe there was such a thing as “private life” in a medieval village, and maybe “red-haired John” really was a reprobate in his, but nonetheless, red-haired John performed all his communal functions — the ones that kept the community vital, and often quite literally alive — perfectly. You know exactly who is failing to hold up his end in a medieval village, and can censure him for it, objectively — either you’re at mass or you’re not; either you paid your tithe or you didn’t; and since the sacrament of “confession” took place in the open air — Cardinal Borromeo’s confessional box being an integral part of the Counter-Reformation — everyone knew how well you performed, or didn’t, in whatever “private” life you had.

Take all that away, and you’ve got process guys who feel it’s their sacred duty — as in, necessary for their own souls’ sake — to infer what’s going on in yours. Strip away the public ritual, and now you have to find some other way to make everyone’s private business public … I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Calvinism is really Karen-ism, and if it IS unfair, I don’t care, because fuck Calvin, the world would’ve been a much better place had he been strangled in his crib.

A man is only as good as the public performance of his public duties. And, crucially, he’s no worse than that, either. Since process guys will always pervert the process in the name of more efficiently reaching the outcome, process guys must always be kept on the shortest leash. Send them down to the countryside periodically to reconnect with the laboring masses …

Severian, “Faith vs. Works”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-07.

January 14, 2025

QotD: Ritual in medieval daily life

December 26, 2023

The awe-inducing power of volcanoes

Ed West considers just how much human history has been shaped by vulcanology, including one near-extinction event for the human race:

A huge volcano has erupted in Iceland and it looks fairly awesome, both in the traditional and American teenager senses of the word.

Many will remember their holidays being ruined 13 years ago by the explosion of another Icelandic volcano with the epic Norse name Eyjafjallajökull. While this one will apparently not be so disruptive, volcano eruptions are an under-appreciated factor in human history and their indirect consequences are often huge.

Around 75,000 years ago an eruption on Toba was so catastrophic as to reduce the global human population to just 4,000, with 500 women of childbearing age, according to Niall Ferguson. Kyle Harper put the number at 10,000, following an event that brought a “millennium of winter” and a bottleneck in the human population.

In his brilliant but rather depressing The Fate of Rome, Harper looked at the role of volcanoes in hastening the end of antiquity, reflecting that “With good reason, the ancients revered the fearsome goddess Fortuna, out of a sense that the sovereign powers of this world were ultimately capricious”.

Rome’s peak coincided with a period of especially clement climatic conditions in the Mediterranean, in part because of the lack of volcanic activity. Of the 20 largest volcanic eruptions of the last 2,500 years, “none fall between the death of Julius Caesar and the year AD 169”, although the most famous, the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, did. (Even today it continues to reveal knowledge about the ancient world, including a potential treasure of information.)

However, the later years of Antiquity were marked by “a spasm” of eruptions and as Harper wrote, “The AD 530s and 540s stand out against the entire late Holocene as a moment of unparalleled volcanic violence”.

In the Chinese chronicle Nan Shi (“The History of the Southern Dynasties”) it was reported in February 535 that “there twice was the sound of thunder” heard. Most likely this was a gigantic volcanic explosion in the faraway South Pacific, an event which had an immense impact around the world.

Vast numbers died following the volcanic winter that followed, with the year 536 the coldest of the last two millennia. Average summer temperature in Europe fell by 2.5 degrees, and the decade that followed was intensely cold, with the period of frigid weather lasting until the 680s.

The Byzantine historian Procopius wrote how “during the whole year the sun gave forth its light without brightness … It seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear”. Statesman Flavius Cassiodorus wrote how: “We marvel to see now shadow on our bodies at noon, to feel the mighty vigour of the sun’s heat wasted into feebleness”.

A second great volcanic eruption followed in 540 and (perhaps) a third in 547. This led to famine in Europe and China, the possible destruction of a city in Central America, and the migration of Mongolian tribes west. Then, just to top off what was already turning out to be a bad decade, the bubonic plague arrived, hitting Constantinople in 542, spreading west and reaching Britain by 544.

Combined with the Justinian Plague, the long winter hugely weakened the eastern Roman Empire, the combination of climatic disaster and plague leading to a spiritual and demographic crisis that paved the way for the rise of Islam. In the west the results were catastrophic, and urban centres vanished across the once heavily settled region of southern Gaul. Like in the Near East, the fall of civilisation opened the way for former barbarians to build anew, and “in the Frankish north, the seeds of a medieval order germinated. It was here that a new civilization started to grow, one not haunted by the incubus of plague”.

July 9, 2023

Imperial Rome

In UnHerd, Freddie Sayers talks to historian and podcaster Tom Holland about his latest book, Pax:

To his army of ardent followers, Tom Holland has a unique ability to bring antiquity alive. An award-winning British historian, biographer and broadcaster, his thrilling accounts offer more than a mere snapshot of life in Ancient Greece and Rome. In Pax — the third in his encyclopaedic trilogy of best-sellers narrating the rise of the Roman Empire — Holland establishes how peace was finally achieved during the Golden Age, with a forensic recreation of key lives within the civilisation, from emperors to slaves.

This week, Holland came to the UnHerd club to talk about Roman sex lives, Christian morality, and the rise and fall of empires. Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

Freddie Sayers: Let’s kick off with the very first year in your book.

Tom Holland: It opens in AD 68, which is the year that Nero committed suicide: a key moment in Roman history, and a very, very obvious crisis point. Nero is the last living descendant of Augustus, and Augustus is a god. To be descended from Augustus is to have his divine blood in your veins. And there is a feeling among the Roman people that this is what qualifies you to rule as a Caesar, to rule as an emperor. And so the question that then hangs over Rome in the wake of Nero’s death is: what do we do now? We no longer have a descendant of the divine Augustus treading this mortal earth of ours. How is Rome, how is its empire, going to cohere?

FS: It seemed to me, when I was reading Pax, that there was a recurring theme: a movement between what’s considered decadence, and then a reassertion of either a more manly, martial atmosphere, or a return to how things used to be — to the good old days. With each new emperor in this amazing narrative, it often feels like there’s that same kind of mood, which is: things have gotten a bit soft. We’re going to return to proper Rome.

TH: It’s absolutely a dynamic that runs throughout this period. And it reflects a moral anxiety on the part of the Romans that has been characteristic of them, really, from the time that they start conquering massively wealthy cities in the East — the cities in Asia Minor or Syria or, most of all, Egypt. There’s this anxiety that this wealth is feminising them, that it’s making them weak, it’s making them soft — even as it is felt that the spectacular array of seafood, the gold, the splendid marble with which Rome can be beautified, is what Romans should have, because they are the rulers of the world.

That incredible tension is heightened by class anxieties. There’s no snob like a senatorial snob. They want to distinguish themselves from the masses. But at the same time, there’s the anxiety that if they do this in too Greek a way, in too effeminate a way, then are they really Romans? And so the whole way through this period, the issue of how you can enjoy your wealth, if you are a wealthy Roman, without seeming “unRoman”, is an endearing tension. And of course, there is no figure in the empire who has to wrestle with that tension more significantly than Caesar himself.

FS: The 100-odd years that you’re covering in this volume is a period of great peace and prosperity and power, and yet at each juncture, it feels like there’s this anxiety. That’s what surprised me as a reader. There’s this sense of the precariousness of the empire — maybe it’s become softer, maybe it’s decadent, or maybe it needs to rediscover how it used to be.

TH: And, you see, this is the significance of AD 69, “the Year of the Four Emperors”, because the question is, are the cycles of civil war expressive of faults? Of a kind of dry rot in the fabric of the Empire that is terminal? Of the anger of the gods? And whether, therefore, the Romans need to find a way to appease the gods so that the whole Empire doesn’t collapse. This is an anxiety that lingers for several decades. It looks to us like this is the heyday of the Empire. They’re building the Colosseum, they’re building great temples everywhere. But they’re worrying: “Have the gods turned against us?”

And of course, there is a very famous incident, 10 years after the Year of the Four Emperors, which is the explosion of Vesuvius. And this is definitely seen as another warning from the gods, because it coincides with a terrible plague in Rome, and it coincides with the incineration (for the second time in a decade) of the most significant temple in Rome — the great temple to Jupiter on the Capitol, the most sacred of the seven hills of Rome.

Romans offer sacrifice to the gods or you pay dues to the gods rather in the way that we take out an insurance policy. And if the gods are busy burying famous towns on the Bay of Naples beneath pyroclastic flows, or sending plagues, or burning down temples, then this, to most, is evidence that the Roman people have not been paying their dues. So a lot of what is going on — certainly in the imperial centre — in this period, is an attempt to try and get the Roman Empire back on a stable moral footing.

April 8, 2023

QotD: Rome’s “excess labour” problem

Back when historians actually cared about the behavior of real people, they looked at big-picture stuff like “labor mobility”. Ever wonder why all that cool shit Archimedes invented never went anywhere? The Romans had a primitive steam turbine. Why did it remain a clever party trick? Romans were fabulous engineers — these are the guys, you’ll recall, who just built a harbor in a convenient spot when they couldn’t find a good enough natural one. Surely their eminently practical brains could spot some use for these gizmos …?

The thing is — as old-school historians would tell you if any were still alive — technology is all about saving labor. Physical labor, mental labor, same deal. Consider the abacus, for instance. It’s a childishly simple device — it’s literally a child’s toy now — but think about actually doing math with it, when the only alternative is scratch paper. How much time do you save, not having to jot things down (remember where you put the jottings, etc.)?

I’m sure you see where this is going. The Romans did NOT lack for labor. They had, in fact, the exact opposite problem: Far, far too much labor. It’s almost a cliché to say that a particular group in the ancient world didn’t qualify as a “civilization” until they started putting up as ginormous a monument as they could figure out. They raised monuments for lots of reasons, of course, but not least among them was the excess-labor problem. What else are you supposed to do with the tribe you just conquered? Unless you want to wipe them out, to the last old man, woman, and child, slavery is the only humane solution.

If that’s true, then the opposite should also hold — technological innovation starts with a labor shortage. Survey says … yep. There’s a reason the Scientific Revolution dates to the Renaissance: The massive labor shortage following the Black Death. That this is also the start of the great age of exploration is also no accident. While the labor (over-)supply was fairly constant in the ancient world, once technological innovation really got going, the labor-supply pendulum started swinging wildly. The under-supply after the Black Death led to over-supply once technological work-arounds were discovered; that over-supply was exported to the colonies, which were grossly under-supplied, etc.

In short: If you want to know what kind of society you’re going to have, look at labor mobility.

Severian, “Excess Labor”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-07-28.

September 20, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 4 – Justinian, The Hand of God

seangabb

Published 1 Jan 2022Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

July 26, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 4 – The Ostrogoths in Italy

seangabb

Published 10 May 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western Provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

May 3, 2022

History of Rome in 15 Buildings 07. The Column of Marcus Aurelius

toldinstone

Published 27 Sep 2018Roman troops file in neat lines over raging rivers and trackless mountains. They crush barbarian forces in battle after battle, leaving fields of corpses in their wake. Villages burn, captives weep – and the lonely figure of the philosopher-emperor leads his legions to victory. So the spiraling reliefs of the Column of Marcus Aurelius, subject of the seventh episode in our History of Rome, represent the brutal conflict that turned back the first wave of the barbarian invasions.

If you enjoyed this video, you might be interested in my book Naked Statues, Fat Gladiators, and War Elephants: Frequently Asked Questions about the Ancient Greeks and Romans. You can find a preview of the book here:

https://toldinstone.com/naked-statues…

If you’re so inclined, you can follow me elsewhere on the web:

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorian…

https://www.instagram.com/toldinstone/To see the story and photo essay associated with this video, go to:

https://toldinstone.com/the-column-of…Thanks for watching!

April 25, 2022

QotD: The 15th century as a “mulligan”

I can’t really recommend Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars or Johan Huizinga’s The Autumn of the Middle Ages as casual reading — you don’t have to be a specialist in the field to appreciate them (I’m not), but it surely helps. Nonetheless they’re worth a browse (provided you can find them), for a glimpse inside the head of a once vital, but now senescent, culture.

As I’ve written here before, the 15th century makes much more sense if you consider it a “mulligan” century, a do-over — an attempt to stuff the Early Modern cat back into the High Medieval bag in the wake of the Black Death. One cannot, of course, say that thus-and-such should’ve happened in history — history is the study of what actually did happen — but it’s clear that the Black Death was a giant hiccup in the otherwise “natural” progression from Middle Ages to Early Modern. It was all there in embryo in 1340; had the Black Death not hit the pause button for half a century, the great ructions of the early 1500s would’ve hit in the early 1400s. And they no doubt would’ve been a lot less severe, too — without the Black Death, the “Martin Luther” of 1417 might’ve been one of the great reforming Popes.

Read Huizinga or Duffy, and you get the overwhelming impression of bright children playing dress up. Everything’s cranked way past eleven. Like kids, they know that grownups do these things, and because they’re bright kids they have some idea why grownups do it … but not really, and the nuances utterly escape them. Huizinga tells the story of some churchman who ostentatiously drinks every drink he’s given in five swallows, one for each of Jesus’s wounds … obnoxious enough, but then he goes that characteristically Late Medieval extra mile — because both blood and water flowed from Christ’s side, he takes the second swallow in two gulps.

Knights vow to not open one of their eyes until they’ve met the Turk in battle. Another churchman rails against the kitschy little figurines found in burghers’ homes, a carving of the Virgin Mary with a door in her stomach. You open it up, and there’s the Trinity. Bad enough, but again the Late Medieval twist: He’s not upset at the figure as such (even though it’s the next best thing to idolatry); he’s pissed because you see the entire Trinity there, and not just Jesus, as is theologically proper. Speaking of Mary, academics debate, in all apparent seriousness, whether or not she was an “active participant” in Our Lord’s conception. And so on: Creeping to the Cross, endless novenas and rosaries and vigils, the whole spastically ostentatious public piety of the devotio moderna. The Imitation of Christ is great, everyone should read it, but imagine people doing all that in public, and not in the cloister as Kempis intended.

The old, exhausted, Alzheimery (it’s a word) dregs of a once vital and vibrant spirituality. Sound familiar?

Severian, “Alt Discussion Thread: Sacraments and Superstitions”, Founding Questions, 2022-01-18.

March 19, 2022

Belisarius: War & Plague

Epic History TV

Published 18 Mar 2022Download Endel here, first 100 downloads get 1 week of free audio experiences!

https://app.adjust.com/b8wxub6?campai…Big thanks to Legendarian for Total War: Attila gameplay footage, check out his YouTube channel here: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCOI2…

Big thanks also to our series consultant Professor David Parnell of Indiana University Northwest, who you can follow on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/byzantineprof

Total War: Attila gameplay footage used with kind permission of Creative Assembly – buy the game here: https://geni.us/qDreR

Support Epic History TV on Patreon from $1 per video, and get perks including ad-free early access & votes on future topics https://www.patreon.com/EpicHistoryTV

Original artwork by Miłek Jakubiec https://www.artstation.com/milek

Recommended reading (as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases):

Procopius, History of the Wars https://geni.us/L3Pgc

The Wars of Justinian by Michael Whitby https://geni.us/Xxrd3

Rome Resurgent by Peter Heather https://geni.us/ZFoU1

The Armies of Ancient Persia: the Sassanians by Kaveh Farrokh https://geni.us/jMQo3z

Late Roman Cavalryman AD 236–565 (Osprey) by Simon MacDowall https://geni.us/XMGl

Buy EHTV t-shirts, hoodies, mugs and stickers here! teespring.com/en-GB/stores/epic-histo…

Music from Filmstro: https://filmstro.com/?ref=7765

Get 20% off an annual license with this exclusive code:EPICHISTORYTV_ANN“Rites” by Kevin MacLeod https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song…

License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license#EpicHistoryTV #RomanEmpire #EasternRomanEmpire #Justinian #Belisarius #ByzantineEmpire #Romans #Ostrogoths

December 17, 2021

Scott Alexander on the risk of ancient plagues returning

The other day, Scott Alexander responded to a hair-on-fire New York Magazine piece of hysteria-mongering about climate change warming up arctic zones that may still harbour ancient plagues that can return:

I’m a little nervous talking about this, because I am not a microbiologist. But I haven’t seen the proper experts address this properly, so I’ll try, and if I’m wrong you guys can shout me down.

(Also, the real microbiologists are apparently “self-injecting [3.5 million year old bacteria] just out of curiosity” and we should probably stay away from them for now)

I think we probably don’t have to worry very much about ancient diseases from millions of years ago.

Animal diseases can’t trivially become contagious among humans. Sometimes an animal disease jumps from beast to man, like COVID or HIV, but these are rare and epochal events. Usually they happen when the disease is very common in some population of animals that lives very close to humans for a long time. It’s not “one guy digs up a reindeer and then boom”.

If a plague is so ancient that it’s from before humans evolved, it’s probably not that dangerous. In theory, it could be dangerous for whatever animal it originally evolved for — a rabbit plague infecting rabbits, or an elephant plague infecting elephants. And then maybe after many rabbits are infected, some human might eat an infected rabbit and get unlucky, and the plague might mutate to affect humans. But I don’t think this is any more likely than any of the zillion plagues that already infect rabbits jumping to humans, and nobody is worrying about those.

The story about anthrax is a distraction. The fact that someone got anthrax from a corpse frozen in permafrost is irrelevant; there is anthrax now, and you could get it from a perfectly fresh corpse or living animal if you wanted. It’s adapted to animals and it can’t spread from person to person. Just because you got an irrelevant-to-humans modern animal disease when you dug up a modern animal, doesn’t mean you’re going to get a dangerous-to-humans disease from an ancient animals.

But I’m more concerned about recent human plagues coming back.

Not bubonic plague; that one is another distraction. The reason we don’t get more Black Deaths isn’t because yersinia pestis died off or mellowed out. It’s because we have good sanitation and pest control.

But the 1918 Spanish flu has, as far as I know, legitimately died out. Lots of people like saying that in a sense it’s still with us. This NEJM paper (with a celebrity author!) points out that it’s the ancestor of all existing flu strains. But most of these flu strains are less infectious than it was. This didn’t make sense to me the first, second, or third time I asked about it: why would a flu evolve into an inferior flu? Sure, it might evolve into a less deadly flu because it’s perfectly happy being more infectious but less deadly. But I think the Spanish flu was also especially infectious; so why would it evolve away from that?

November 22, 2021

A new study may show that “Justinian’s plague” reached Britain before Constantinople

Instapundit linked to a news release on a recent Cambridge study on the plague which devastated the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Justinian I, but which may have come through an as-yet undiscovered northern European path that reached the British Isles well before appearing within the Eastern Roman territories:

Illustration of the Hagia Sophia from European History: An outline of its development by George Burton Adams, 1899.

Wikimedia Commons

“Plague sceptics” are wrong to underestimate the devastating impact that bubonic plague had in the 6th–8th centuries CE, argues a new study based on ancient texts and recent genetic discoveries.

The same study suggests that bubonic plague may have reached England before its first recorded case in the Mediterranean via a currently unknown route, possibly involving the Baltic and Scandinavia.

The Justinianic Plague is the first known outbreak of bubonic plague in west Eurasian history and struck the Mediterranean world at a pivotal moment in its historical development, when the Emperor Justinian was trying to restore Roman imperial power.

For decades, historians have argued about the lethality of the disease; its social and economic impact; and the routes by which it spread. In 2019-20, several studies, widely publicised in the media, argued that historians had massively exaggerated the impact of the Justinianic Plague and described it as an “inconsequential pandemic”. In a subsequent piece of journalism, written just before COVID-19 took hold in the West, two researchers suggested that the Justinianic Plague was “not unlike our flu outbreaks”.

In a new study, published in Past & Present, Cambridge historian Professor Peter Sarris argues that these studies ignored or downplayed new genetic findings, offered misleading statistical analysis and misrepresented the evidence provided by ancient texts.

Sarris says: “Some historians remain deeply hostile to regarding external factors such as disease as having a major impact on the development of human society, and ‘plague scepticism’ has had a lot of attention in recent years.”

Sarris, a Fellow of Trinity College, is critical of the way that some studies have used search engines to calculate that only a small percentage of ancient literature discusses the plague and then crudely argue that this proves the disease was considered insignificant at the time.

Sarris says: “Witnessing the plague first-hand obliged the contemporary historian Procopius to break away from his vast military narrative to write a harrowing account of the arrival of the plague in Constantinople that would leave a deep impression on subsequent generations of Byzantine readers. That is far more telling than the number of plague-related words he wrote. Different authors, writing different types of text, concentrated on different themes, and their works must be read accordingly.”

July 24, 2021

History Hijinks: Rome’s Crisis of the Third Century

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 23 Jul 2021Local Empire Too Stubborn To Die — Field Historian Blue is here at the scene of Ancient Rome with more on the Crisis of the Third Century.

SOURCES & Further Reading

https://www.britannica.com/place/anci… + Aurelian, Postumus, Zenobia

The Great Courses The Roman Empire: From Augustus to The Fall of Rome lectures 13 14 and 15, “From Commodus to Caracalla”, “The Crisis of the Third Century” and “Diocletian and Late Third-Century Reforms”, by Gregory Aldrete

The Enemies of Rome Chapter 20 “Parthia, Persia, Palmyra” by Stephen KershawPartial Tracklist: “Scheming Weasel”, Sneaky Snitch”, “Marty Gots A Plan” Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com)Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b…Content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

PODCAST: https://overlysarcasticpodcast.transi…

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/osp

MERCH LINKS: http://rdbl.co/osp

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

From the comments:

Facundo Cadaa

2 hours ago

Thumbnail: “Rome’s big crisis”Do you have any idea how little that narrows it down?

July 16, 2021

The lure of London and agricultural specialization in post-Black Death England

In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the “push” and “pull” theories to account for the vast growth of London and how that urban growth strongly encouraged specialization in English agriculture to feed the great city:

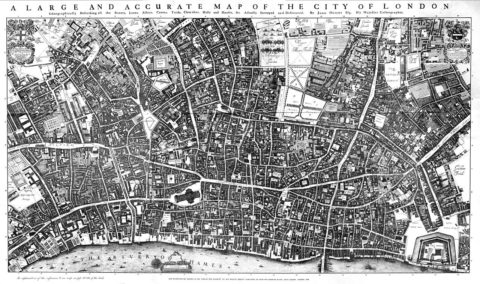

The 1677 original of this map is 8 feet 5 inches by 4 feet 7 inches, in 20 sheets. In 1894 the British Museum granted permission to the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society to make a reduced copy, of which the original of this scan is a copy. The L&M Society copy apparently did not match the dissected sheets perfectly, and the misjoins can be seen in places in this reproduction.

Scanned copy of reproduction in Maps of Old London (1908) of Ogilby & Morgan’s Map of London.

Something significant happened to the English countryside in the century before 1650. Although England’s population merely recovered to its pre-Black Death high of about 5 million, the economy was transformed. Having once been an overwhelmingly agrarian society, by 1650 a small but unprecedented proportion of the population now lived in cities, and less than half of the workforce was employed in agriculture. The country had de-agrarianised, and most remarkably of all, its food was still grown at home.

[…]

One possibly explanation is that there was some special change in England’s agricultural technology that increased its productivity, requiring fewer and fewer people, and possibly even driving them off the land, so that they were forced to find alternative employment. This thesis comes in various forms, many of which I’m still coming to grips with, but broadly speaking it implies a “push” from the fields, and into industry and the cities. Desperate, and unable to demand high wages, these cheaper workers should have stimulated industry’s growth.

The alternative, however, is that there was nothing very special or innovative about English agriculture, and that instead there was an even larger increase in the demand for workers in industry and services. The thesis implies a “pull” into industry and the cities, causing people to abandon agriculture for more profitable pursuits, and thereby making England’s agriculture de facto more productive — something that may or may not have actually been accompanied by any changes to agricultural technology, depending on how much slack there was in how the labourers or land had been employed.

The push thesis implies agricultural productivity was an original cause of England’s structural transformation; the pull thesis that it was a result. The evidence, I think, is in favour of a pull — specifically one caused by the dramatic growth of London’s trade.

Even though the population eventually recovered from the massive impact of the Black Death, not all of the land that was under plough was returned to active farming and a much greater diversity of uses for rural land emerged, including more pastures for grazing livestock, and small cash crops to be sold into the cities (especially into London).

With the dramatic growth of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the more intensive methods came to be in much higher demand. Indeed, the extraordinary pull of the city’s growth resulted in English agriculture becoming increasingly specialised. Not only were there millions of acres of pasture still left that could be returned to the plough, but despite the relative fall in the prices of livestock, some areas actually became even more devoted to pasture. Many of the villages that had been abandoned after the Black Death were, even by the 1870s, over half a millennium later, still not being farmed. With wealthy Londoners demanding more varied diets, with meat and dairy, the various regions of England discovered their comparative advantages rather than all shifting to grain. There was thus extra room for agriculture to become more productive simply by devoting the best land for pasture to pasture, and the best soils for arable to arable, then trading the produce with one another, rather than have each area try to be self-sufficient. It’s something we also see in the decline of grains like rye, especially near London, to be replaced by wheat — the switching of a crop best-suited to local subsistence, to one that could be sold elsewhere and in bulk for cash.

In general, the south and east of England became increasingly arable, while the north-west concentrated on pasture. Yet there were also exceptions to be made for London’s particular wants. Thus, county Durham converted more land to arable to feed the miners of Newcastle coal, used to heat London’s homes; and the county of Middlesex, now largely disappeared under London’s own expansion, specialised in pasture for horses, rather than feeding people, so as to feed the city’s main sources of transportation. As the writer Daniel Defoe put it in the 1720s, “this whole Kingdom, as well the people, as the land, and even the sea, in every part of it, are employed to furnish something, and I may add, the best of everything, to supply the city of London with provisions.”

June 4, 2021

The Peloponnesian War

Epimetheus

Published 21 Oct 2018The Peloponnesian War (extended Video)

Support new videos from Epimetheus on Patreon!

https://www.patreon.com/Epimetheus1776

From the comments:

Epimetheus

2 years ago (edited)

On Spartan society I left out the council of five ephors who were elected annually and shared power with the two kings. This video is a little less edited and recorded partially earlier this year and this evening — sorry if the audio sounds a little all over the place — but I thought some of you may enjoy a finished video rather than one that does not get released — let me know what you think of this longer less polished style of video in contrast to the shorter version of this videoI have increasingly committed to using most of my time on this channel writing researching editing drawing and narrating these videos by myself, I love doing it and would not like to go back to working full time in a cubicle (doing boring stuff) if you want to help me out with upgrading my software and equipment (I use a slow old computer and a tablet) you can do so on Patreon https://www.patreon.com/Epimetheus1776

Even if it is just a single dollar I greatly appreciate you taking the time and your generosity

May 25, 2021

536 AD – Worst Year in History

Kings and Generals

Published 11 May 2021Start speaking a new language in 3 weeks with Babbel

Get 6 months FREE when you sign up for 6 months!

HERE: https://go.babbel.com/6plus6-youtube-…

Kings and Generals’ historical animated documentary series on the history of Ancient Civilizations continues with a video on the year 536 AD, which many historians consider the worst year in history, as plague, famine, volcanic eruption, and extreme weather patterns changed the fate of the millions, especially influencing Sassanid and Eastern Roman Empires.

Support us on Patreon: http://www.patreon.com/KingsandGenerals or Paypal: http://paypal.me/kingsandgenerals We are grateful to our patrons and sponsors, who made this video possible: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1o…

Art and animation: Haley Castel Branco

Narration: Officially Devin (https://www.youtube.com/user/OfficiallyDevin)

Script: Matt Hollis

Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals

Podcast ► Google Play: http://bit.ly/2QDF7y0 iTunes: https://apple.co/2QTuMNG

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/KingsGenerals

Instagram ► http://www.instagram.com/Kings_Generals

Production Music courtesy of EpidemicSound

#Documentary #WorstYearInHistory #536