We all know that barren cat ladies of both sexes and all 57+ genders are the poz’s storm troopers. As I’ve written here probably ad nauseam, you can’t beat Trigglypuff, because — and only because — she has more free time than you do. You have a life, a job, a family, hobbies, interests. She doesn’t. Hell, you have to sleep sometime. She doesn’t, because the Trigglypuffs of the world are by definition jacked up on powerful prescription psychotropics. You just can’t beat that.

You just can’t beat it. But […] Our Thing has lots of potential Trigglypuffs. They’re called “incels,” I’m informed, but whatever the nomenclature, there are a lot of young single dudes out there who while away their pointless hours with video games and porn. Those are our potential storm troopers (it’s a metaphor, FBI goons). Why haven’t we weaponized them? (again: metaphor).

It’s probably as simple as giving them a role model. It goes without saying that your “incel” (or whatever) was raised by women. Even if there was a biological male living in the house during his childhood, it’s a thousand to one he was just that: a cohabiting male. Certainly not a father. And even if by some miracle he was, the poor guy can only do so much. You’ve got to let your sons out of the house sometime … where they’ll immediately be snapped up by the sour, shrieking cat ladies that control our educational system, our media, our professions, our culture. Both the son and his father have to be very, very hard-headed, and not a little lucky, to escape a poz infection …

… and that’s the best-case scenario. For the worst, look around — you’ll find incel and his soy-enfeebled twerp of a “male” parent cowering under the bed, scrubbing their hands and faces with Lysol, while Mommy scolds and caterwauls on Facebook.

There are role models out there, y’all. Stoicism in general, and Marcus Aurelius in particular, have seen a real upswing in popularity, especially on “Game” sites. This doesn’t represent a return to a Classical education; it’s that Marcus seems to be — Marcus is — a worthwhile role model for a fatherless boy. Strip out the “credits” at the start of book one and a few of the denser, more philosophical passages, and you could subtitle Meditations “how to drop your nuts on the carpet and act like a fucking man for once.” Loosely translated, of course.

Severian, “Be a Centurion!”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-04-07.

July 10, 2020

QotD: Marcus Aurelius for the incel demographic

June 30, 2020

QotD: Ideologies and belief systems

It’s really not a good thing because it manifests itself not only in individual psychopathologies, but also in social psychopathologies. That’s this proclivity of people to get tangled up in ideologies, and I really do think of them as crippled religions. That’s the right way to think about them. They’re like religion that’s missing an arm and a leg but can still hobble along. It provides a certain amount of security and group identity, but it’s warped and twisted and demented and bent, and it’s a parasite on something underlying that’s rich and true. That’s how it looks to me, anyways. I think it’s very important that we sort out this problem. I think that there isn’t anything more important that needs to be done than that. I’ve thought that for a long, long time, probably since the early ’80s when I started looking at the role that belief systems played in regulating psychological and social health. You can tell that they do that because of how upset people get if you challenge their belief systems. Why the hell do they care, exactly? What difference does it make if all of your ideological axioms are 100 percent correct?

People get unbelievable upset when you poke them in the axioms, so to speak, and it is not by any stretch of the imagination obvious why. There’s a fundamental truth that they’re standing on. It’s like they’re on a raft in the middle of the ocean. You’re starting to pull out the logs, and they’re afraid they’re going to fall in and drown. Drown in what? What are the logs protecting them from? Why are they so afraid to move beyond the confines of the ideological system? These are not obvious things. I’ve been trying to puzzle that out for a very long time. […]

Nietzsche’s idea was that human beings were going to have to create their own values. He understood that we had bodies and that we had motivations and emotions. He was a romantic thinker, in some sense, but way ahead of his time. He knew that our capacity to think wasn’t some free-floating soul but was embedded in our physiology, constrained by our emotions, shaped by our motivations, shaped by our body. He understood that. But he still believed that the only possible way out of the problem would be for human beings themselves to become something akin to God and to create their own values. He talked about the person who created their own values as the overman, or the superman. That was one part of the Nietzschean philosophy that the Nazis took out of context and used to fuel their superior man ideology. We know what happened with that. That didn’t seem to turn out very well, that’s for sure.

Jordan B. Peterson, “Biblical Series I: Introduction to the Idea of God” {transcript], jordanbpeterson.com, 2018-03-12.

June 28, 2020

QotD: Nietzsche’s views on Christianity

Nietzsche was a devastating critic of dogmatic Christianity — Christianity as it was instantiated in institutions. Although, he is a very paradoxical thinker. One of the things Nietzsche said was that he didn’t believe the scientific revolution would have ever got off the ground if it hadn’t been for Christianity and, more specifically, for Catholicism. He believed that, over the course of a thousand years, the European mind had to train itself to interpret everything that was known within a single coherent framework — coherent if you accept the initial axioms. Nietzsche believed that the Catholicization of the phenomena of life and history produced the kind of mind that was then capable of transcending its dogmatic foundations and concentrating on something else. In this particular case it happened to be the natural world.

Nietzsche believed that Christianity died of its own hand, and that it spent a very long time trying to attune people to the necessity of the truth, absent the corruption and all that — that’s always part of any human endeavour. The truth, the spirit of truth, that was developed by Christianity turned on the roots of Christianity. Everyone woke up and said, or thought, something like, how is it that we came to believe any of this? It’s like waking up one day and noting that you really don’t know why you put a Christmas tree up, but you’ve been doing it for a long time and that’s what people do. There are reasons Christmas trees came about. The ritual lasts long after the reasons have been forgotten.

Nietzsche was a critic of Christianity and also a champion of its disciplinary capacity. The other thing that Nietzsche believed was that it was not possible to be free unless you had been a slave. By that he meant that you don’t go from childhood to full-fledged adult individuality; you go from child to a state of discipline, which you might think is akin to self-imposed slavery. That would be the best scenario, where you have to discipline yourself to become something specific before you might be able to reattain the generality you had as a child. He believed that Christianity had played that role for Western civilization. But, in the late 1800s, he announced that God was dead. You often hear of that as something triumphant but for Nietzsche it wasn’t. He was too nuanced a thinker to be that simpleminded. Nietzsche understood — and this is something I’m going to try to make clear — that there’s a very large amount that we don’t know about the structure of experience, that we don’t know about reality, and we have our articulated representations of the world. Outside of that there are things we know absolutely nothing about. There’s a buffer between them, and those are things we sort of know something about. But we don’t know them in an articulated way.

Jordan B. Peterson, “Biblical Series I: Introduction to the Idea of God” {transcript], jordanbpeterson.com, 2018-03-12.

June 20, 2020

History-Makers: Confucius

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 19 Jun 2020Welcome to the challenge run of History-Makers, where I attempt to give insightful historical context to someone whose backstory is almost entirely blank.

SOURCES & Further Reading: Confucius: A Very Short Introduction by Gardner, China: A History by Keay, The Analects of Confucius, The Mencius.

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

June 10, 2020

QotD: “God is Dead”

We have this articulated space that we can all discuss. Outside of that we have something that’s more akin to a dream that we’re embedded in. It’s an emotional dream that we’re embedded in, and that’s based, at least in part, on our actions. […] What’s outside of that is what we don’t know anything about at all. The dream is where the mystics and artists live. They’re the mediators between the absolutely unknown and the things we know for sure. What that means is that what we know is established on a form of knowledge that we don’t really understand. If those two things are out of sync — if our articulated knowledge is out of sync with our dream — then we become dissociated internally. We think things we don’t act out and we act out things we don’t dream. That produces a kind of sickness of the spirit. Its cure is something like an integrated system of belief and representation.

People turn to things like ideologies, which I regard as parasites on an underlying religious substructure, to try to organize their thinking. That’s a catastrophe and what Nietzsche foresaw. He knew that, when we knocked the slats out of the base of Western civilization by destroying this representation, this God ideal, we would destabilize and move back and forth violently between nihilism and the extremes of ideology. He was particularly concerned about radical left ideology and believed — and predicted this in the late 1800s, which is really an absolute intellectual tour de force of staggering magnitude — that in the 20th century hundreds of millions of people would die because of the replacement of these underlying dream-like structures with this rational, but deeply incorrect, representation of the world. We’ve been oscillating back and forth between left and right ever since, with some good sprinkling of nihilism and despair. In some sense, that’s the situation of the modern Western person, and increasingly of people in general.

Jordan B. Peterson, “Biblical Series I: Introduction to the Idea of God” {transcript], jordanbpeterson.com, 2018-03-12.

June 8, 2020

QotD: Death and life

Facing death — and life — with courage, awareness, and honesty can bring out the best in us and focus our minds on what matters most: gratitude and love. Gratitude for a chance at life, given the biological reality that those hundred billion people who lived before us were, in fact, only a tiny fraction of the many trillions of people who could have been born but were not. The chance encounter of sperm and egg that led to each of us could just as well have produced someone else, and you would never know it because there would be no you to know. Once born, we are each unique, a concatenation of genes and brains with thoughts, feelings, memories, histories, and points of view that can never be duplicated, here or in the hereafter. Our sentience — yours, mine, everyone’s — is ours alone and like no other anywhere in the cosmos. We are given this one chance to live, some four score trips around the sun, a brief but glorious moment in the cosmic drama unfolding on this provisional proscenium. Given all we know about the universe and the laws of nature, that is the most any of us can reasonably hope for. Fortunately, it is enough. It is the soul of life. It is heaven on earth.

Michael Shermer, Heavens on Earth: The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, Immortality, and Utopia, 2018.

May 30, 2020

QotD: The “Americanization” of German philosophy

This popularization of German philosophy in the United States is of peculiar interest to me because I have watched it occur during my own intellectual lifetime, and I feel a little like someone who knew Napoleon when he was six. I have seen value relativism and its concomitants grow greater in the land than anyone imagined. Who in 1920 would have believed that Max Weber’s technical sociological terminology would someday be the everyday language of the United States, the land of the Philistines, itself in the meantime become the most powerful nation in the world? The self-understanding of hippies, yippies, yuppies, panthers, prelates and presidents has unconsciously been formed by German thought of a half-century earlier; Herbert Marcuse’s accent has been turned into a Middle Western twang; the echt Deutsch label has been replaced by a Made in America label; and the new American life-style has become a Disneyland version of the Weimar Republic for the whole family.

Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 1987.

May 19, 2020

QotD: Amour-propre

The French have this wonderful word, amour-propre, so much better than our English “self-love.” It comes, with its edge, from La Rochefoucauld, his urbane and scintillating Maxims in the seventeenth century. It is the arch-flatterer, “more artful than the most artful of mankind.” In parallel, it comes from Blaise Pascal, who observes that Christianity is the only cure. Then it comes again through Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in the “enlightened” eighteenth century, who thought the primitive savages incapable of amour-propre, because they lacked the gilt-framed mirrors of sophisticated society, in which their pride might be reflected. He imagines it the source of all corruption; and with some authority, for he was himself among the most corrupt of men — this Rousseau who taught us all to “blame society.”

Really there is nothing new under the sun, and the concept comes much earlier from Saint Augustine of Hippo who in his City of God calls it in Latin, amor sui, and puts it about the centre of his review of human tawdriness. That, in turn, is how it came to Pascal: via the French Augustinians, with whom Pascal was in thick, about the time he was writing his Lettres provinciales. One might add, contre Rousseau (and perhaps with Joseph de Maistre) that it goes back farther, to Adam and Eve.

Ye devill appeals to Eve’s amour-propre. She then appeals to Adam’s. That’s how this whole wretched mess got started. Note that this couple predeceased all Rousseau’s noble savages, and that the field anthropologists have since discovered that the primitive tribal types are a lot like us. Which is to say, bad, in many colourful ways, and quite invariably self-regarding.

David Warren, “Amour-propre”, Essays in Idleness, 2016-06-01.

May 6, 2020

QotD: The French philosophes and the “lower orders”

Apart from the different philosophical status they assigned to reason and virtue, the one issue where the contrast between the British and French Enlightenments was sharpest was in their attitudes to the lower orders. This is a distinction that has reverberated through politics ever since. The radical heirs of the Jacobin tradition have always insisted that it is they who speak for the wretched of the earth. In eighteenth-century France, they claimed to speak for the people and the general will. In the nineteenth century, they said they represented the working classes against their capitalist exploiters. In our own time, they have claimed to be on the side of blacks, women, gays, indigenes, refugees, and anyone else they define as the victims of discrimination and oppression. Himmelfarb’s study demonstrates what a façade these claims actually are.

The French philosophes thought the social classes were divided by the chasm not only of poverty but, more crucially, of superstition and ignorance. They despised the lower orders because they were in thrall to Christianity. The editor of the Encyclopédie, Denis Diderot, declared that the common people had no role in the Age of Reason: “The general mass of men are not so made that they can either promote or understand this forward march of the human spirit.” Indeed, “the common people are incredibly stupid,” he said, and were little more than animals: “too idiotic — bestial — too miserable, and too busy” to enlighten themselves. Voltaire agreed. The lower orders lacked the intellect required to reason and so must be left to wallow in superstition. They could be controlled and pacified only by the sanctions and strictures of religion which, Voltaire proclaimed, “must be destroyed among respectable people and left to the canaille large and small, for whom it was made.”

Keith Windschuttle, “Gertrude Himmelfarb and the Enlightenment”, New Criterion, 2020-02.

May 1, 2020

QotD: Cynicism

Somewhere around that same eighth-grade mark where we all experimented with being mean, we get the idea that believing in things makes you a sucker — that good art is the stuff that reveals how shoddy and grasping people are, that good politics is cynical, that “realism” means accepting how rotten everything is to the core.

The cynics aren’t exactly wrong; there is a lot of shoddy, grasping, rottenness in the world. But cynicism is radically incomplete. Early modernist critics used to complain about the sanitized unreality of “nice” books with no bathrooms. The great modernist mistake was to decide that if books without sewers were unrealistic, “reality” must be the sewers. This was a greater error than the one it aimed to correct. In fact, human beings are often splendid, the world is often glorious, and nature, red in tooth and claw, also invented kindness, charity and love. Believe in that.

Megan McArdle, “After 45 Birthdays, Here Are ’12 Rules for Life'”, Bloomberg View, 2018-01-30.

April 19, 2020

QotD: Early Greek philosophers

The greatest name in this succession of first researchers was that of Democritus, who became known as the laughing philosopher. In his ethical teaching great store was set by cheerfulness.

Democritus was still living when the new scientific movement suffered a violent reverse. It was in Athens, a center of conservatism, that the opposition arose and it was brilliantly headed. The leader was no other than Socrates, who despaired of the possibility of scientific knowledge. Even Aristotle, who pioneered in some branches of science, rejected the atomic theory. Between these two great names came that of Plato, who believed the ultimate realities to be not atoms but triangles, cubes, spheres and the like. By a kind of analogy he extended this doctrine to the realm of abstract thought. If, for example, perfect spheres exist, why should not perfect justice exist also? Convinced that such perfect justice did exist, he sought in his own way to find it. The ten books of his Republic record only part of his searchings of the mind. At the core of all this thinking lies the doctrine that the eternal, unchangeable things are forms, shapes, models, patterns, or, what means the same thing in Greek, “ideas.” All visible things are but changing copies of unchanging forms.

The Epicurean Revival

After the great triumvirate of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle had passed away the scientific tradition was revived with timely amendments by Epicurus. In his time it was the prevalent teaching that the qualities of compound bodies must be explained by the qualities of the ingredients. If the compound body was cold, then it must contain the cold element air, if moist, water, if dry, earth, and if hot, fire. Even Aristotle sanctioned this belief in the four elements. Epicurus, on the contrary, maintained that colorless atoms could produce a compound of any color according to the circumstances of their combination. This was the first definite recognition of what we now know as chemical change.

The Stoic Reaction

Epicurus was still a young man when Athenian conservatism bred a second reaction to the new science. This was headed by Zeno, the founder of Stoicism. His followers welcomed a regression more extreme than that of Aristotle in respect to the prime elements. For the source of their physical theories they went back to Heracleitus, who believed that the sole element was fire. This was not a return to the Stone Age but it was a longish way in that direction.

This Heracleitus had been a doleful and eccentric individual and became known, in contrast to the cheerful Democritus, as the weeping philosopher. His gloom was perpetuated in Stoicism, a cheerless creed, of which the founder is described as “the sour and scowling Zeno.” Epicurus, on the contrary, urged his disciples to “wear a smile while they practiced their philosophy.”

Running parallel to these contrasting attitudes toward life and physical theories was an equally unbroken social divergence. Platonism as a creed was always aristocratic and in favor in royal courts. “I prefer to agree with Plato and be wrong than to agree with those Epicureans and be right,” wrote Cicero, and this snobbish attitude was not peculiar to him. Close to Platonism in point of social ranking stood Stoicism, which steadily extolled virtue, logic, and divine providence. This specious front was no less acceptable to hypocrites than to saints. Aptly the poet Horace, describing a pair of high-born hypocrites, mentions “Stoic tracts strewn among the silken cushions.” Epicureanism, on the contrary, offered no bait to the silk-cushion trade. It eschewed all social distinction. The advice of the founder was to have only so much regard for public opinion as to avoid unfriendly criticism for either sordidness or luxury. This was no fit creed for the socially or politically ambitious.

Norman W. DeWitt, “Epicurus: Philosophy for the Millions”, The Classical Journal, 1947-01.

April 16, 2020

QotD: Nietzsche’s ideas

… an accurate and intelligent account of Nietzsche’s ideas, by one who has studied them and understands them, is, as Mawruss Perlmutter would say, yet another thing again. Seek in What Nietzsche Taught, by Willard H. Wright, and you will find it. Here in the midst of the current obfuscation, are the plain facts, set down by one who knows them. Wright has simply taken the eighteen volumes of the Nietzsche canon and reduced each of them to a chapter. All of the steps in Nietzsche’s arguments are jumped; there is no report of his frequent disputing with himself; one gets only his conclusions. But Wright has arranged these conclusions so artfully and with so keen a comprehension of all that stands behind them that they fall into logical and ordered chains, and are thus easily intelligible, not only in themselves, but also in their interrelations. The book is incomparably more useful than any other Nietzsche summary that I know. It does not, of course, exhaust Nietzsche, for some of the philosopher’s most interesting work appears in his arguments rather than in his conclusions, but it at least gives a straightforward and coherent account of his principal ideas, and the reader who has gone through it carefully will be quite ready for the Nietzsche books themselves.

These principal ideas all go back to two, the which may be stated as follows:

- Every system of morality has its origin in an experience of utility. A race, finding that a certain action works for its security and betterment, calls that action good; and, finding that a certain other action works to its peril, it calls that other action bad. Once it has arrived at these valuations it seeks to make them permanent and inviolable by crediting them to its gods.

- The menace of every moral system lies in the fact that, by reason of the supernatural authority thus put behind it, it tends to remain substantially unchanged long after the conditions which gave rise to it have been supplanted by different, and often diametrically antagonistic conditions.

In other words, systems of morality almost always outlive their usefulness, simply because the gods upon whose authority they are grounded are hard to get rid of. Among gods, as among office-holders, few die and none resign. Thus it happens that the Jews of today, if they remain true to the faith of their fathers, are oppressed by a code of dietary and other sumptuary laws — i.e., a system of domestic morality — which has long since ceased to be of any appreciable value, or even of any appreciable meaning, to them. It was, perhaps, an actual as well as a statutory immorality for a Jew of ancient Palestine to eat shell-fish, for the shell-fish of the region he lived in were scarecly fit for human food, and so he endangered his own life and worked damage to the community of which he was a part when he ate them. But these considerations do not appear in the United Sates of today. It is no more imprudent for an American Jew to eat shell-fish than it is for him to eat süaut;ss-und-sauer. His law, however, remains unchanged, and his immemorial God of Hosts stands behind it, and so, if he would be counted a faithful Jew, he must obey it. It is not until he definitely abandons his old god for some modern and intelligible god that he ventures upon disobedience. Find me a Jew eating oyster fritters and I will show you a Jew who has begun to doubt very seriously that the Creator actually held the conversation with Moses described in the ninteenth and subsequent chapters of the Book of Exodus.

H.L. Mencken, “Transvaluation of Morals”, The Smart Set, 1915-03.

April 4, 2020

QotD: The danger of studying philosophy

I quickly learned that […] many of my professors valued paradoxical and obscure arguments. And I got pretty good at making them. In an essay on Wallace Stevens, I concluded by asserting, “If everything is nothing, then that nothingness is everything. For poetry to encompass one, it encompasses the other. When Stevens’s mind of winter descends into the inescapable nothingness of his subjectivity, he has claimed for himself the totality of everything.” I don’t know what this means. But I wrote it and I was rewarded for it.

I knew my analysis of Wallace Stevens would please my professor, but I was bothered by a nagging thought that I really didn’t understand Wallace Stevens. I wondered if my graduate school training just amounted to a parlor trick. Last year, at my high school, the students enjoyed arguing if a hotdog is a sandwich, the millennial equivalent of asking how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. The hotdog question made its way to the whiteboard in our staff lounge. By the time I arrived, my colleagues had written their responses. Some argued that a hot dog is not a sandwich because a sandwich requires two pieces of bread and a hotdog bun isn’t supposed to separate. Others averred that it most definitely is a sandwich: Meat between bread is a sandwich, end of story. I saw these responses and thought, “Simpletons!” before putting my graduate education to work: “In order to determine if a ‘hotdog is a sandwich,’ we must first determine the proper understanding of ‘is’ for if we do not grasp the ontological necessity of being itself, we fall into an abyss wherein ‘being’ is and is not itself and thus a hotdog is and is not a sandwich for it is and is not its very self.” I was quite amused by the whole situation until a colleague told me that a student had seen the whiteboard and said he wanted to study philosophy so that he could write like me.

S. A. Dance, “Incomprehension 501: Intro to Graduate School”, Quillette, 2018-03-06.

March 24, 2020

QotD: “Desacralizing the State”

Winston Churchill famously proclaimed democracy to be the least-worst government. Alas, quotability is not the same thing as wisdom. Worst at what, Sir Winston?

Speaking of quotable-yet-loony folks, Aristotle defined Man as “the political animal,” and as such had an answer to our question: The State’s purpose, Aristotle said, is to promote virtue.

Let’s leave the contentious topic of “virtue” aside, and step back to the definition of “Man.” Man isn’t a political animal. Man is a purpose-finding animal, an explaining animal. We simply can’t resist the siren song of teleology. We all live under some kind of State; therefore, we assume that “The State” must have a purpose. It’s in our DNA; we can’t do otherwise, but … we might be wrong. Perhaps “self-organization into some kind of government” is just one of Humanity’s givens, like “sexual dimorphism*” or “requires oxygen.” Maybe “government” just IS.

A dangerous thought, that. If it’s true, it desacralizes the State — the worship of which, I think we all agree, has driven all the major political events in the West since at least 1789. Historian Herbert Butterfield called the 20th century’s great mass movements “giant organized forms of self-righteousness,” but he could’ve taken that a step further — “popular” government of any sort invariably becomes a giant organized form of self-righteousness. People being people — that is, teleology-addled monkeys — it can’t be any other way. The State, since it exists, must exist to do something. What better something to do than to promote virtue?

So we’re back to Aristotle. But it looks like Aristotle stole a base. As a rule, people aren’t virtuous. Why else would they need the State to promote virtue? And yet, the State is made up of nothing but people. Aristotle also said that a cause can’t give something to an effect that it, the cause, doesn’t already have. So how, then, can the State — which, like Soylent Green, is made of people — itself make people virtuous?

See what I mean about this teleology stuff? The mind rebels. The State is a human thing. Humans made it, and every human act, we’re hardwired to believe, has a purpose behind it. That hardwiring may lead us into incoherence in under three steps, but so far as I know, I’m the only guy in the history of Political Science ever to suggest that government just … kinda … IS. That it evolved with us, and thus all our airy-fairy noodling about Divine Right and We the People and the Vanguard of the Proletariat and whatnot are just foolish blather about what’s basically still a monkey troop.

[…]

All this would be just philosophy-wank, better suited to a dorm room bull session after a few bong rips, if not for the fact that “desacralizing the State” has to be the #1 project of any viable Dissident movement. The State, as a human production, has only such “goals” as we give it … and, being made up of nothing but humans, is going to be as good at achieving those goals as we humans generally are at achieving any of our goals …

Severian, “The Least-Worst Government?”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-12-21.

February 11, 2020

Animal “rights”

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, L. Neil Smith republished a short essay he wrote for the March 1996 edition which is still fully relevant today:

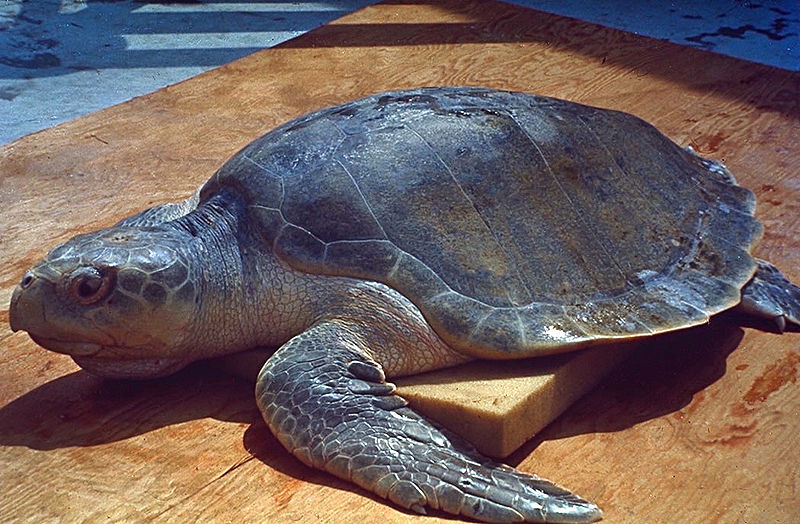

An olive ridley sea turtle, a species of the sea turtle superfamily.

NASA image via Wikimedia Commons.

Last Friday I watched an episode of X-Files in which innocent zoo animals were being abducted — apparently by benign, superior UFOsies (the ones who mutilate cattle and stick needles in women’s bellies) — to save them from a despicable mankind responsible for the erasure of thousands of species every year.

Or every week, I forget which.

I was reminded of a debate I’d found myself involved in about sea turtles; I’d suggested that laws prohibiting international trade in certain animal products be repealed so the turtles might be privately farmed and thereby kept from extinction. After all, who ever heard of chickens being an endangered species? From the hysteria I provoked — by breathing the sacred phrase “animal rights” and the vile epithet “profit” in one sentence — you’d have thought I’d demanded that the Virgin be depicted henceforth in mesh stockings and a merry widow like Frank N. Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

That debate convinced me of two things. First: I wasn’t dealing with politics, here, or even philosophy, but with a religion, one that would irrationally sacrifice its highest value — the survival of a species — if the only way to assure it was to let the moneylenders back into the temple. Its adherents abominate free enterprise more than they adore sea turtles.

Second (on evidence indirect but undeniable): those who cynically constructed this religion have no interest in the true believers at its gullible grassroots, but see it simply as a new way to pursue the same old sinister objective. A friend of mine used to refer to “watermelons” — green on the outside, red on the inside — who use environmental advocacy to abuse individualism and capitalism. Even the impenetrable Rush Limbaugh understands that animal rights and related issues are just another way socialism pursues its obsolete, discredited agenda.

In my experience, those who profess to believe in animal rights usually don’t believe in human rights. That’s the point, after all.