Wee Nips

Published 29 Jun 2025Born between 1954 and 1965? You might be part of the forgotten generation — Generation Jones — wedged awkwardly between Boomers and Gen X.

In this video, we break down what it means to be a Joneser, why we’re all still jonesing for something better, and how our weird hybrid powers (like remembering phone numbers and setting up Wi-Fi) just might save the world.

If you’ve ever used aluminum foil on rabbit ears or fixed a TV by smacking it, this one’s for you.

March 1, 2026

Generation Jones EXPLAINED: The Lost Generation Nobody Talks About

February 15, 2026

QotD: The love of long-distance train travel

Why is it that I love, or used to love, trains so much? I thought about this often when I was effectively banned, by the virus, from my normal daily journey between Oxford and London, 63 miles each way. Even now, in bare modern trains systematically stripped of character and romance, there can be a glorious seclusion in a long-distance train that does not stop too much. The soft and distant landscape rolls by, and at any time I can look up and see a familiar hill, church, or stretch of woodland. I can name much of what I see, and have walked over a great deal of it, purposely seeking to know the land better. If I am traveling from the North of England to London, I always try to change at York, to the hourly nonstop train to the capital. The feeling of peace and irresponsibility that spreads through me as the train heaves itself out of the station is a special joy. For two hours nobody can bother me. For two hours I will not be disturbed. For two hours I will be enclosed in a warm and comfortable space, again passing through familiar towns and fields along the route so wonderfully described by Philip Larkin in “The Whitsun Weddings“, until the brakes tighten and I am in prosaic London. And it seems to me that everyone else on that train will be similarly calmed and soothed.

Of course, the accursed cell phone and the even more accursed smartphone have penetrated the seclusion. And alas, there are no more dining cars, a delight now almost completely abolished by spiteful managements, and available mainly on ridiculous super-luxury trains such as the pastiche Orient Express. Yet no restaurant meal I have ever had, including the pressed duck at the old Tour D’Argent in Paris (before it became a museum where you could eat the exhibits), has surpassed the breakfasts, lunches, teas, and dinners I have eaten in trains.

I think of the wonderful bacon and eggs, accompanied by soda bread, on the cross-border Belfast-to-Dublin flyer in Ireland; the vast plates of pork and dumplings accompanied by Pilsener beer on the somnolent Zapadny Express from Nuremberg to Prague; the fresh pancakes and maple syrup at breakfast on the California Limited, with antelopes fleeing from the train somewhere between Dodge City and Albuquerque; the first sip of tea from the samovar, served in a glass in an ornate silver holder, on the Red Star night sleeper from Moscow to Leningrad; the first glass of wine on a sunny September evening as the Rome Express, an hour out of Paris, clattered southward past the faintly minatory cathedral tower at Sens. Then there were the toasted teacakes near Grantham on the southbound Flying Scotsman, and the superb galley-cooked steak on the upper deck of the Chicago-bound Capitol Limited, as it climbed westward through the evening into the forests beyond Harper’s Ferry and up the Potomac valley.

Peter Hitchens, “Why I Love Trains”, First Things, 2020-07-16.

February 11, 2026

The rise and fall of the “Western” on TV and in movies

Ted Gioia reconsiders his childhood loathing of the TV western (because of massive over-exposure to the genre):

I hated cowboys when I was a youngster. Not real cowboys — I never met a single gunslinger, cowpoke, or desperado in in my urban neighborhood. My loathing was reserved for cowboys on TV.

And they were everywhere.

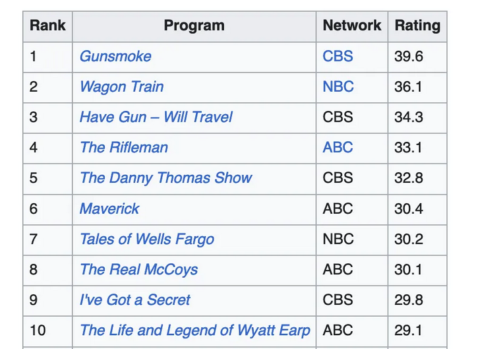

At one point, eight of the top ten shows on the flickering tube were westerns. And it got worse from there — Hollywood kept churning out more and more cowboy movies and TV series. I tried to avoid them, as did many of my buddies, but it was like dodging bullets in Dodge. There was nowhere to hide.

That’s because our parents loved these simple stories of frontier justice. They couldn’t get enough of them. And when they weren’t watching them on TV, they dragged us off to movie theaters to see The Magnificent Seven (128 minutes), The Alamo (138 minutes) or How the West Was Won (an excruciating 164 minutes).

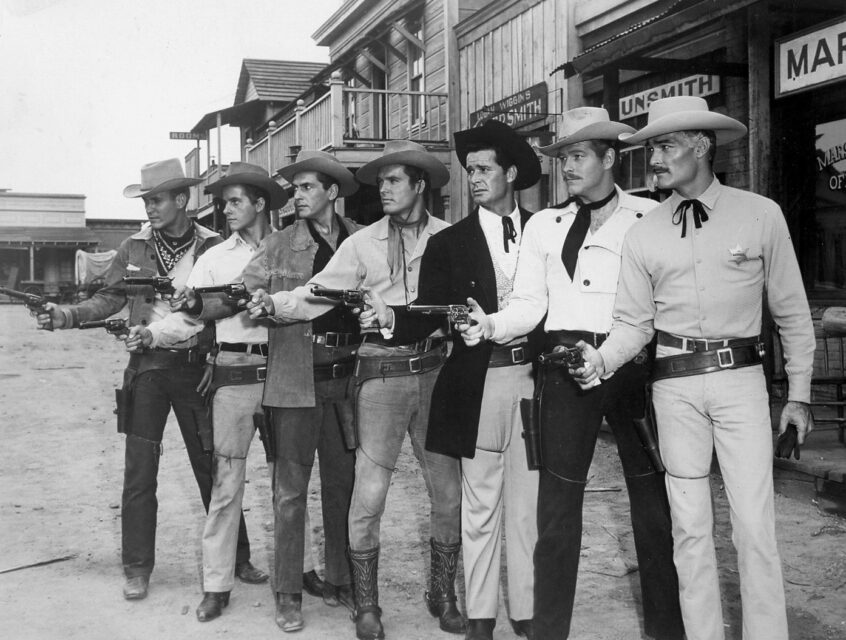

In 1959, Warner Bros posed some of their TV cowboy stars in a single photo (Source)

[…]

Many aspects of these films still put me off. I struggle with the clichés and tired formulas. But I’ve gradually acquired an affection for the genre — or maybe an affection for the audiences of an earlier day who could put such trust and faith in a sheriff or US marshal or gunslinger for hire.

Do any of us have that kind of faith in any authority figure nowadays? I doubt it. But I wish we could. And that’s impressed powerfully on my mind when I see Gary Cooper take on outlaws in the deserted western street of High Noon. Or James Stewart confront the dangerous Liberty Valance. Or John Wayne battle with a gang of desperadoes in Rio Bravo.

So forget all the shootouts and cattle drives and fancy roping. The real foundation of the western genre was moral authority. And Hollywood never let you forget it — that’s why heroes wore white hats and villains dressed in black.

The audience didn’t even have to think about it.

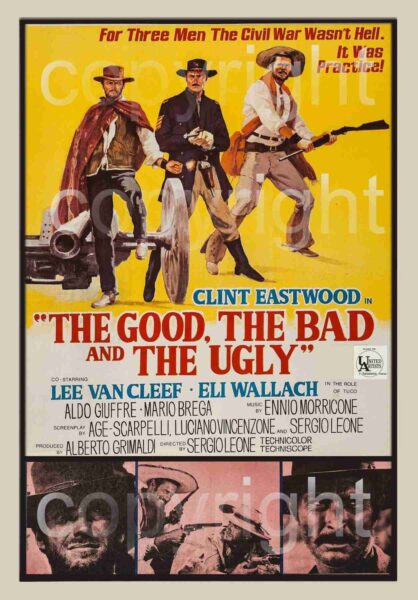

[…]Because that’s exactly what happened to the western. Just consider the unsettling film The Good, the Bad and the Ugly — which came out around the time the western genre died. Despite the movie’s title, it’s hard to identify any character in this film as good — instead they merely differ in their degrees of badness and ugliness.

And the same is true of The Wild Bunch or Once Upon a Time in the West and so many other films from that era. There are no heroes on display here, only various pathways into nihilism.

So long John Wayne. Hello Friedrich Nietzsche.

But this made perfect sense. The entire US of A was traumatized by the Vietnam War, and then Watergate — along with assassinations, riots, sex, drugs, and rock & roll. The moral sureness of the Eisenhower years, along with the complacent righteousness of so much of the public started to erode. At first it happened slowly, and then rapidly.

The classic western could not survive this.

January 23, 2026

The Rise and Fall of Watneys – human-created video versus AI slop

YouTuber Tweedy Misc released what he believed was the first attempt to discuss Watneys Red Barrel, the infamous British beer that triggered the founding of the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA). His video didn’t show up in my YouTube recommendations, but a later AI slop video that clearly used Tweedy’s video as fodder did get recommended and I even scheduled it for a later 2am post because it seemed to be the only one on the topic. I’m not a fan of clanker-generated content, but I was interested enough to set my prejudices aside for a treatment of something I found interesting. Tweedy’s reaction video, on the other hand, did appear in my recommendations a few weeks later, and I felt it deserved to take precedence over the slop:

And here’s the AI slop video if you’re interested:

Dear Old Blighty

Published Dec 20, 2025Discover how Watneys Red Barrel went from Britain’s biggest-selling beer to its most hated pint in just a few short years. This video explores how corporate brewing, keg beer, and ruthless pub control nearly destroyed traditional British ale, sparked a nationwide consumer revolt, and gave birth to CAMRA. From Monty Python mockery to boycotts in local pubs, Watneys became a national punchline and a cautionary tale in business failure. Learn how one terrible beer accidentally saved British brewing culture, revived real ale, and reshaped how Britain drinks forever.

#Watneys #BritishBeer #UKNostalgia #RealAle #CAMRA #BritishPubs #RetroBritain #LostBrands #BeerHistory #DearOldBlighty

December 25, 2025

QotD: Christmas dinner

An advertisement in my Sunday paper sets forth in the form of a picture the four things that are needed for a successful Christmas. At the top of the picture is a roast turkey; below that, a Christmas pudding; below that, a dish of mince pies; and below that, a tin of —’s Liver Salt.

It is a simple recipe for happiness. First the meal, then the antidote, then another meal. The ancient Romans were the great masters of this technique. However, having just looked up the word vomitorium in the Latin dictionary, I find that after all it does not mean a place where you went to be sick after dinner. So perhaps this was not a normal feature of every Roman home, as is commonly believed.

Implied in the above-mentioned advertisement is the notion that a good meal means a meal at which you overeat yourself. In principle I agree. I only add in passing that when we gorge ourselves this Christmas, if we do get the chance to gorge ourselves, it is worth giving a thought to the thousand million human beings, or thereabouts, who will be doing no such thing. For in the long run our Christmas dinners would be safer if we could make sure that everyone else had a Christmas dinner as well. But I will come back to that presently.

The only reasonable motive for not overeating at Christmas would be that somebody else needs the food more than you do. A deliberately austere Christmas would be an absurdity. The whole point of Christmas is that it is a debauch — as it was probably long before the birth of Christ was arbitrarily fixed at that date. Children know this very well. From their point of view Christmas is not a day of temperate enjoyment, but of fierce pleasures which they are quite willing to pay for with a certain amount of pain. The awakening at about 4 a.m. to inspect your stockings; the quarrels over toys all through the morning, and the exciting whiffs of mincemeat and sage-and-onions escaping from the kitchen door; the battle with enormous platefuls of turkey, and the pulling of the wishbone; the darkening of the windows and the entry of the flaming plum pudding; the hurry to make sure that everyone has a piece on his plate while the brandy is still alight; the momentary panic when it is rumoured that Baby has swallowed the threepenny bit; the stupor all through the afternoon; the Christmas cake with almond icing an inch thick; the peevishness next morning and the castor oil on December 27th — it is an up-and-down business, by no means all pleasant, but well worth while for the sake of its more dramatic moments.

Teetotallers and vegetarians are always scandalized by this attitude. As they see it, the only rational objective is to avoid pain and to stay alive as long as possible. If you refrain from drinking alcohol, or eating meat, or whatever it is, you may expect to live an extra five years, while if you overeat or overdrink you will pay for it in acute physical pain on the following day. Surely it follows that all excesses, even a one-a-year outbreak such as Christmas, should be avoided as a matter of course?

Actually it doesn’t follow at all. One may decide, with full knowledge of what one is doing, that an occasional good time is worth the damage it inflicts on one’s liver. For health is not the only thing that matters: friendship, hospitality, and the heightened spirits and change of outlook that one gets by eating and drinking in good company are also valuable. I doubt whether, on balance, even outright drunkenness does harm, provided it is infrequent — twice a year, say. The whole experience, including the repentance afterwards, makes a sort of break in one’s mental routine, comparable to a week-end in a foreign country, which is probably beneficial.

George Orwell, “In praise of Christmas”, Tribune, 1946-12-20.

December 13, 2025

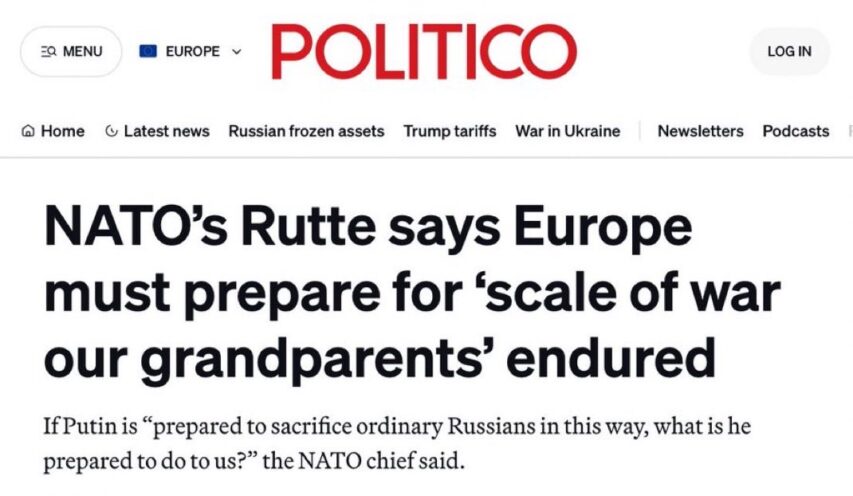

“Europe must prepare for ‘scale of war our grandparents’ endured”

On the social media site formerly known as Twitter, @InfantryDort responds to the NATO Secretary General’s announcement that Europe should gird its collective loins for combat on a scale similar to the World Wars:

Fighting Like Our Grandparents, Without Becoming Like Them?What a strange moment it is to belong to the warrior culture in the West.

To watch your society fracture in real time. To see cohesion traded for comfort. And to be told to prepare for wars of national survival while the nation itself dissolves at home.

Europe, in particular, has already spent its strongest men. Bled out across the killing fields of the 20th century. Now it is warned to fight like its grandparents once did.

The warning is correct, but not in the way people think.

Violence, chaos, entropy … these are the default state. They pull on human societies the way gravity pulls on matter. Left alone, everything falls.

Function requires resistance. A rocket escapes gravity only by burning fuel. An exoskeleton works only by pushing back. Civilization is no different.

You cannot fight a war of national survival abroad when the nation no longer coheres at home. When families are exposed, trust is gone, and the social fabric has been cut to make the room feel larger.

It’s not strength. It is just removing load-bearing walls and mistaking openness for stability.

The lesson: Our grandparents didn’t just fight with weapons. They fought with unity, discipline, restraint, and shared purpose.

Without those, you don’t get their victories. You only inherit their destruction. And all without the moral scaffolding that survived it. Wars are not won by nostalgia. They are won by societies that still function.

TLDR: Few sane men will go off to war in a far away land when hordes of their previous battlefield opponents have moved into their neighborhoods.

Update, 13 December: On the social media site formerly known as Twitter, John Carter responds to Rutte’s speech:

These are just empty rituals indulged in by the clerisy of hermetically sealed institutions. They have no ability to mobilize for war. The financialized economies they preside over have been hollowed out by deindustrialization, over-regulation, and climate hysteria. The populations of their countries are deracinated, alienated, and ethnoculturally fragmented. They did all of this themselves, deliberately and systematically, over decades, because it benefited them to do so. It made the institutions stronger, and enriched them as a class. That it came at the expense of the viability of their societies didn’t bother them in the slightest.

Membership in the institutional theocracy is predicated on absolute alignment with internal narratives. Those narratives are simply whatever the theocracy needs to believe at any given moment to justify itself. At the moment, they need to believe that nothing fundamental has shifted in Western countries since the end of WWII, in particular that it is still in principle possible to mobilize a (non-existent) industrial base for wartime production, and that it is possible to motivate an alienated population to fight. They also need to believe that the loathing with which native populations regard them is inorganic, a function of narrative warfare from the troll farms of foreign adversaries, and that this resentment can be effectively curtailed with censorship and propaganda.

Internally they see themselves as very serious people, statesmen and generals, guardians of the moral order.

From the outside, they are clowns engaged in a pantomime.

December 7, 2025

“Anglofuturism” – slogan or beacon of hope?

At Without Diminishment, Robert King argues for Anglofuturism as the most hopeful path forward from the morass all of the Anglosphere seems to be bogged down in:

Born in the digital backwaters of podcasts and Substacks, Anglofuturism has climbed into public view like a rocket nearing the King Charles III Space Station, gathering both attention and indignation as it ascends.

The New Statesman mutters about it being rooted in “nostalgia“, while the far-left activist group Hope Not Hate insists it is something deeply sinister. Yet their agitation merely confirms a familiar sequence. First, they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, and then you win.

At its essence, Anglofuturism is a project of civilisational renewal.

It begins with the conviction that Britain’s decline is not destiny but a decision, and the consequence of decades of political miscalculations that consider the national story to be over, Britain’s very own “end of history”.

Just turn on the news and you will see evidence for this everywhere. Strategic islands like the Chagos Islands surrendered to the vassals of hostile powers. A once-thriving energy sector crippled by the ritual self-flagellation of net zero policies, despite abundant North Sea oil resources.

The capital city of London, once envied for its composure, now deafened by the shrill chants of imported grievances, “From the river to the sea”. Britain was once a country whose streets were said to be paved with gold, according to the legend of Dick Whittington.

Today, they are paved with boarded banks, betting slips, and vape shops. The country’s future is already playing out in London, a place where the nation of Britain has faded into the idea of “the Yookay”. Britain is told that because it once colonised, it must now invite colonisation, that because it once conquered, it must now submit.

The result is a people bending ever lower in the hope of forgiveness from a self-appointed virtuous minority at home, and from the ever-growing numbers of strangers who now claim the country as their own.

Anglofuturism is the vanguard against this ideology. It insists that love of one’s civilisation is a duty, not a sin. It binds identity to optimism, and pride to ambition. It seeks to remind Britons that its best days may yet lie ahead, but only if it learns once more to have confidence in itself.

[…]

The policy of splendid isolation simply will not work for the twenty-first century.

Enter CANZUK, the proposed alliance of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Four constitutional monarchies, four democracies, and four maritime powers linked by law, language, and lineage. Together they would represent over 140 million people and a combined GDP exceeding $6 trillion. It would be a realm on which, once again, the sun would never set.

Our shared day of remembrance on November 11 is a reminder that we partake in traditions born of shared sacrifice.

Such a bloc would not be a re-creation of empire, but a confederation of equals who share the responsibilities of defence and trade, coordinating space and science, and projecting stability from north to south and east to west.

It could stand apart from American turbulence, Chinese authoritarianism, and European stagnation, and be a new civilisational pole rooted in innovation and freedom under common law. It could even be a new contender to lead the free world.

Britain is still a nation successful at exporting ideas like capitalism, liberalism, and, regrettably, Blairism. Anglofuturism could be its most powerful export to the Anglosphere yet.

For those of us at the edge of that world, in Cape Town, Perth, or Vancouver, the message of Anglofuturism is that our story is not over. Our civilisation may be weak, even fading, but it can be revived. Doing this will demand the same courage that built it, in the spirit of the pioneers and soldiers, the engineers and thinkers who shaped continents and defended freedom when it was under siege.

October 7, 2025

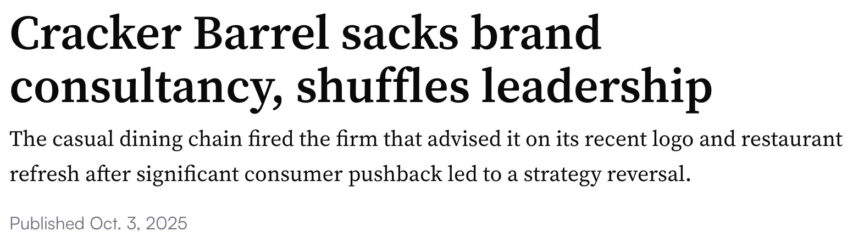

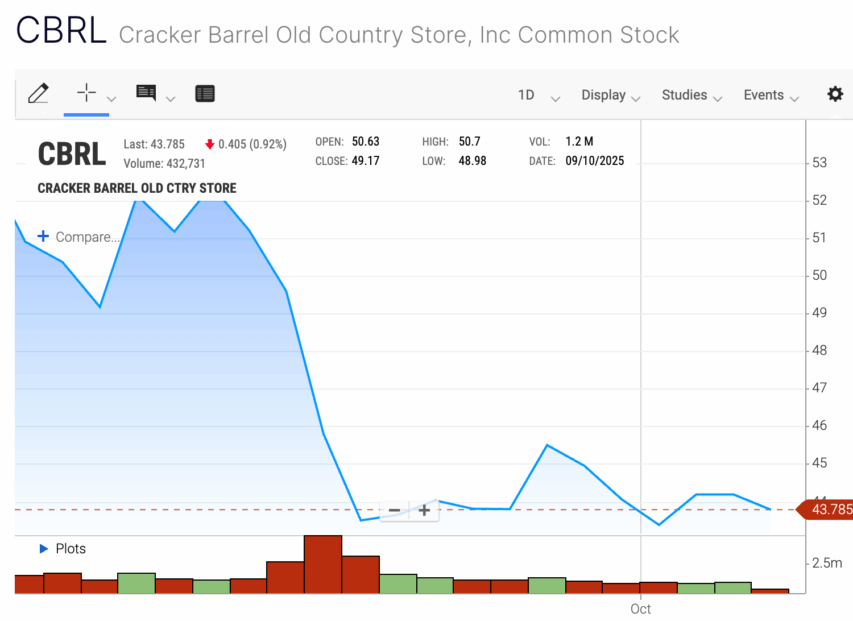

Big management shake-up at Cracker Barrel’s corporate HQ

Back in August, the US chain restaurant field saw a corporation decide that doing what their customers wanted was actually a pretty good strategy … after they’d tried the opposite and nearly gone the way of Bud Light:

Last week was the Red Wedding for Cracker Barrel.

Some senior people who were in the headquarters office last Monday weren’t there anymore as the weekend drew near, some old managers from an earlier corporate culture came back to rewind the clock, and the branding consultant that advised on the now-fatally-wounded rebranding effort was sent packing. The new logo departed. The redesigned stores were acknowledged as a failure and an embarrassment.

[…]

See what they said about the redesign? “We won’t continue with it”. The whole thing collapsed, a $700 million rebrand that slammed into a concrete wall and exploded.

It remains to be seen how much the rebranding of the rebranding will matter, and this is what Cracker Barrel stock looks like in the last month:

Now, a reminder: The New York Times columnist David French explained, just over a month ago, that the controversy over Cracker Barrel’s rebranding was an absurd fake crisis ginned up by right-wing idiots who were just pretending that something had gone wrong at the company. Along with the Sydney Sweeney thing, he concluded that we were watching some “completely frivolous and meaningless cultural disputes,” examples of the way “right-wing media both mobilizes its base and bends political reality”. If you believed that the Cracker Barrel rebranding was poorly done and would alienate the company’s customers, you were falling for an invented reality that was completely meaningless and frivolous.

Then Cracker Barrel fired a bunch of managers and its rebranding consultant, abandoned the rebranding, and apologized profusely, while its stock plummeted.

If you listened to David French, if you trusted the op-ed pages of the New York Times to explain the world to you, your understanding of the most basic outline of factual reality was flipped over, turned precisely upside down. He was only wrong about literally every single detail, completely missing what was happening, what it meant, and what would happen in the near future as a result of it. To listen to this idiot is to abuse your own mind, trapping yourself in the confines of an absurd house of ideological mirrors. He is inevitably wrong, completely wrong, reliably wrong to the point of absolute and unyielding madness.

September 9, 2025

QotD: The horrible 1970s

It should be noted, though, that it really was kind of gross to be alive during the ’70s. You can’t unsee all those hairdos, medallions, and Day-Glo typefaces. You just kind of have to put your head down like a shell-shocked veteran and stride your way grimly through a happier age.

Colby Cosh, “Cinema: recently seen”, ColbyCosh.com, 2005-08-19.

August 29, 2025

Memories of Bournemouth

It’s nearly sixty years since my family emigrated, but I still have golden memories of the family trips to the seaside, although my family went to Scarborough, Whitby, and Redcar rather than the Bournemouth of Pimlico Journal‘s childhood:

“Harvester at Durley Chine” by David Lally is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

At every possible opportunity in the summer weekends of my childhood, my father would take our family down to the coast. Our route to the sea was normally through the medieval city of Salisbury, across the chalk downs of Hardy’s Wessex, and into the piney moors of the New Forest. The destination would nearly always be Bournemouth, the prim, stately model of the British seaside town, perched magisterially on Dorset’s sandstone cliffs, above a long golden strand lapped by the warm waves of the Channel.

Our favourite beach was at Durley Chine, where we could park (for free, greatly appealing to my father) among obscured mansions in the shade of thick-smelling conifers, and make our descent to the shore, where the chine gives way to the rows of huts that line the promenade, and a reassuringly lower-middle class Harvester restaurant. We would while away the hours on the sand until the sky was orange, my mother reading, my father swimming, and my brother and I playing whatever games we could devise, mostly involving the throwing of sand. The day would end with fish and chips under the pines, watching the sun sink over the jurassic cliffs past Poole harbour, the gateway to King Alfred’s stronghold at Wareham.

These were among the most precious times of my early life, and the sights and sounds and smells of that part of the world and the accompanying hazy, worriless bliss are cherished sensations. Though the beach is public, it was one of those places that felt special and individual to my family, as if we had somehow carved out our own summer fief on the crowded shore.

It was on Durley Chine beach, on 24 May 2024, that two innocent women, Amie Grey and Leanne Miles, were attacked by Nasen Saadi, a criminology student from Croydon of Iraqi and Thai heritage. Saadi murdered Grey and left Miles in critical condition, and was sentenced this year to thirty-nine years in prison for his crimes. The incident was part of an escalating pattern of violence, particularly sexual violence, in the Bournemouth area over the past few years, with the beach as the focal point, a pattern which had begun in July 2021 with the brutal rape of a 15-year-old girl by Gabriel Marinoaica, a young man from Walsall who dragged his victim into the sea to commit his attack. Another notable incident occurred eight months later. Afghan asylum seeker and convicted killer Lawangeen Abdulrahimzai (he had shot two fellow Afghans while living illegally in Serbia in 2018, before fleeing to Norway, where his asylum claim was rejected, then travelling to Britain and successfully claiming asylum by pretending to be an unaccompanied fourteen-year-old, despite being an adult) stabbed Thomas Roberts (a local man and qualified precision engineer who had recently applied to join the Royal Marines) to death outside a Subway in the city centre, in a dispute over an e-scooter.

The news stories become relentless from that point. Among many depravities are the sexual assault of a 17-year-old boy by a group of Asian males on 17 June 2023, accompanied the same day by an attempted assault on a 16-year-old girl outside the fish and chip shop on the seafront. A week later, two girls, aged just 10 and 11, who would have been in primary school at the time, were sexually assaulted while swimming in the sea. As far as I can tell, none of these crimes have yet been prosecuted.

Two months after the murder of Amie Grey, on 19 July 2024, a day of delirious warmth culminated in violent clashes between youths, many coming in from London, on the seafront — clashes which were filmed and circulated on social media. In the chaos, a teenage girl was sexually assaulted. Jessica Toale, the freshly-elected Labour MP for Bournemouth West, a seat which had been Tory since its creation in 1950, said after the events of 19 July that crime and anti-social behaviour had become a ‘huge issue’ in contrast to the safe Bournemouth she remembered as a girl, stating that ‘… parents had told [her] that they are concerned about letting their daughters go to the town’. These are almost reactionary words from a Labour MP, and reflective of the mood of anxiety and decline that seems to have enveloped the city, a mood founded on the series of despair-inducing events plaguing residents and visitors. On 30 June, disorder similar to that witnessed in July last year returned to the seafront, with police making arrests across the country in the aftermath.

A week later, on 6 July, a young woman was raped in a public toilet adjoining the beach. The police have charged Mohammed Abdullah, a Syrian asylum seeker living in West London, with the crime.

August 24, 2025

This is Westland Helicopters (1960s)

British Helicopters History

Published 17 Jan 2020Major rationalisation of the UK aircraft industry occurred during the 1960s. With the acquisition of Bristol Helicopters, Fairey Aviation and Saunders-Roe, Westland Helicopters transformed itself into Britain’s only helicopter maker with plants at Yeovil, Weston-super-Mare, Eastleigh, and Hayes, producing helicopters for all roles.

August 23, 2025

Another Bud Light moment: Cracker Barrel gets rid of the cracker

I haven’t been to the United States for more than a decade — not for political reasons, just for financial ones … I haven’t had the money to travel since 2015 — so it’s at least that long since I visited a Cracker Barrel. On our usual driving holidays, we’d stop somewhere like a Cracker Barrel to get a big breakfast to tide us over to our next destination a few hundred miles further down the road. I’d heard that the food quality had dropped after Covid, but I can’t confirm that from personal experience. Here’s ESR’s take on the latest rebranding that has riled up the online commentariat and apparently tanked the company’s stock price:

Today I’m here to talk about why I dislike Cracker Barrel, but dislike the Cracker Barrel rebrand even more.

My first reaction to the outpouring of social-media sentimentality about the destruction of CB’s comfortable old-timey ambience was to stare and wonder if these boosters had gone entirely out of their minds.

Yes, CB was designed to evoke a sort of folk memory of what rural country stores used to be like. But it’s, at best, a gigantized, commoditized, kitschy simulacrum of what they were — Hee Haw as filtered through the mind of an urban-corporate bugman.

Exhibit A for this is the gauntlet you have to run through to get to the food — gift shops that are unrivaled for the utter tastelessness and worthlessness of the cheesy crap on their shelves.

Once you get to the food, well … they serve a decent breakfast. Everything else is bland, homogenized slop.

And yet, I find that I dislike the rebranded look and feel even more. Because at least CB as it was gestured feebly in the direction of something authentic and American. The new look strips out all those vestiges — it has all the character of a generic airport lounge.

If you’re reading this and getting hot under the collar because I’ve impugned an experience that has sentimental value for you … look, I get it, okay? Old CB wasn’t designed for me, nor for anybody else who can unironically describe themselves as urbane, sophisticated cosmopolitans. But in its own pastiched way it had value, value which is now being destroyed.

Certainly the stock market thinks so. CB’s share price has been dropping like a rock — the rebrand is a failure even by corporate-bugman standards.

If the chain needed saving, the right thing to do would have been to double down on the attractive parts. Keep the local memorabilia on the walls, improve the menu, turn down the wince-inducing tackiness of the gift shop. Make it more like the mythical olden days, not less.

But no. Because the CEO is an idiot. I’ve been on a corporate board of directors and I’m here to confirm that if CB’s doesn’t convene an emergency meeting to fire her before the end of the week they are not doing their job.

July 26, 2025

VIA Rail’s premier passenger train, The Canadian

In the National Post, Raymond J. de Souza discovers the aging crown jewel of VIA Rail’s passenger services, The Canadian, which VIA inherited from Canadian Pacific Railway when the country’s long-distance and intercity rail passenger services were merged into a single Crown Corporation in the 1970s:

Canadian Pacific FP7 locomotive 1410 at the head of The Canadian stopped at Dorval, Quebec on 6 September, 1965. The Canadian was Canadian Pacific’s premier passenger train before VIA Rail was formed.

Photo by Roger Puta via Wikimedia Commons.

What did I learn after four days and four nights, some 4,500 kilometres, from Vancouver to Toronto on board Via Rail’s The Canadian? Many things, as it happens.

I learned that The Canadian attracts train aficionados the world over for one of the last great rail journeys on one of the last great trains. The stainless steel rolling stock is 70 years old, the cars having been upgraded along the way, but still rolling as a living part of railway history.

Part of the cultural history Via Rail preserves is superlative meals thrice daily, served in fine style in the dining cars. Four dinners: rack of lamb, beef tenderloin, AAA prime rib, bone-in pork chop. Delicious desserts. Canadian wines and craft beers. Fish eaters and vegans also had options. The question arises ineluctably: Why is the Via Rail food between Montreal and Toronto so horrible?

Perhaps it would be too expensive; The Canadian in sleeper class certainly is. Expense was really the question in the 1870s.

“Could a country of three and a half million people afford an expenditure of one hundred million dollars at time when a labourer’s wage was a dollar a day?” asked Pierre Berton in his 1970 chronicle of that decision, The National Dream.

The cost of not building was greater, argued Sir John A. Macdonald. It was the price of remaining a sovereign continental country. Part of the financing was creative; the Hudson’s Bay Company gave Rupert’s Land to Canada, and Canada paid the contractors partly in free land.

Growing up in Calgary, I presumed that the greatest challenge was putting the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) through the mountains. And it is true that the most spectacular scenery on the route is the Fraser Canyon and the mountains of the Yellowhead Pass. (The Canadian now travels the northern route of the Canadian National (CN) Railway, not the original southern route of the CPR.)

Yet it was the Canadian Shield, thousands of lakes and muskeg atop the hardest rock on earth, that was the real obstacle. John Palliser, one of the 1860s expeditioners between Thunder Bay and the Rockies, reported back that while getting through the mountain passes could be done, the impenetrable land north of Lake Superior was the insuperable problem. And without getting around the Shield, Canada would be constrained, cooped up, with the prairies and mountains and west coast inaccessible.

I’d always hoped to travel The Canadian at some point, but I was never able to afford the tickets at the same time that I had available time to travel, and there’s no hope I’ll ever be able to scrape up the money these days. According to VIA Rail’s website, the trip from Toronto to Vancouver would be between C$5860 to $9460 per person.

May 5, 2025

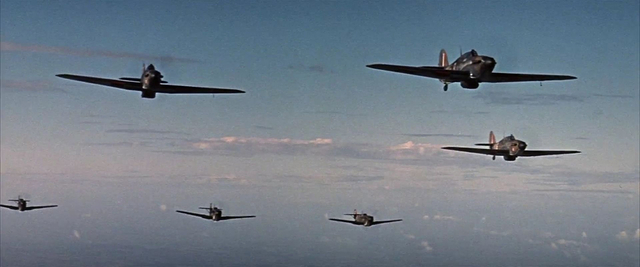

Remembering The Battle of Britain (1969)

At SteynOnline, Rick McGinnis discusses the 1969 film The Battle of Britain, which was considered a financial flop at the time it was released and only turned a profit once home VCR sales provided a new revenue stream — it was how I first watched the movie, although I do remember seeing posters for it at the cinema while it was in theatrical release.

The best recent depictions of the war – my subjective list includes Band of Brothers, The Pacific, Saving Private Ryan, Dunkirk, Das Boot, Greyhound and Letters from Iwo Jima – were mostly made with veterans advising on historical accuracy and mostly being heard. This wasn’t always the case: for at least two decades following the war, when veterans were still thick on the ground, historical accuracy was frequently sacrificed in the interest of adventure, drama, comedy or romance.

(My subjective list includes Kelly’s Heroes, The Dirty Dozen, The Guns of Navarone, D-Day The Sixth of June, Where Eagles Dare, Operation Petticoat, From Here to Eternity and Von Ryan’s Express. Not that these aren’t entertaining, enjoyable films; they just shouldn’t be considered history.)

If there was a turning point – a film that struggled and mostly succeeded in telling a plausibly accurate story about the war to audiences likely to contain not just veterans but civilians with lived memories – it was probably Guy Hamilton’s Battle of Britain, released in 1969, barely thirty years after the event it commemorates.

While in pre-production for the film, 007 producer Harry Saltzman and his co-producer (and veteran RAF pilot) Benjamin Fisz realized that their American backers at MGM were nervous about making a film about something Americans knew little about. This led to The Battle for the Battle of Britain, a short TV documentary about the film and the event that it was based on, hosted and narrated by one of the film’s stars, Michael Caine.

Included with the 2005 collector’s edition DVD of Hamilton’s film, The Battle for the Battle of Britain begins with a series of “man on the street” interviews conducted outside the American embassy in London. Older interview subjects talk vaguely about how they’d admired the British for standing alone against Nazi Germany at the time; younger ones almost unanimously admit that they don’t’ know anything about it. One woman states that she doesn’t wish to give an opinion since she works for the embassy. At the time these interviews were made the average age of a British pilot who fought in the battle and survived would have been around fifty, as the vast majority of the young men who flew to defend England in the summer of 1940 were on either side or twenty.

Making Battle of Britain felt like a duty in 1969; it attracted a cast of big stars who were willing to work for scale just to be involved, but that didn’t stop the film from going massively over schedule and over budget. Historical accuracy was so important that Saltzman and Lisz ended up collecting what became the world’s 35th largest air force, rebuilding wrecked airframes and making planes that had sat on concrete plinths outside museums and airfields flyable again.

The film begins with the fall of France in the spring of 1940, and British pilots and air crew struggling to get back in the air ahead of the rapidly approaching German army. We meet the three RAF squadron leaders who will be at the centre of the action: Caine’s Canfield, Robert Shaw as the curt, intense “Skipper”, and Colin Harvey (Christopher Plummer), a Canadian married to Maggie (Susannah York), an officer in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.

Back across the channel we meet Sir Laurence Olivier as Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command and the man who will lead the English in the air battle to come. Blunt and charmless, Dowding had the unenviable task of telling Sir Winston Churchill, only just appointed Prime Minister, that he doesn’t support his promise to send more fighter squadrons across the Channel to aid the French as they would be squandered in a lost cause and, in any case, he needs every plane and pilot he has to fight the German invasion that’s doubtless coming.

December 25, 2024

Drinker’s Christmas Crackers – It’s a Wonderful Life

The Critical Drinker

Published 17 Dec 2020Join me as I review what may be the ultimate Christmas movie — the 1946 classic starring James Stewart and Donna Reed … It’s a Wonderful Life.