Practical Engineering

Published Jan 16, 2024Let’s dive into the engineering and construction of the Channel Tunnel on its 30th anniversary.

It is a challenging endeavor to put any tunnel below the sea, and this monumental project faced some monumental hurdles. From complex cretaceous geology, to managing air pressure, water pressure, and even financial pressure, there are so many technical details I think are so interesting about this project.

(more…)

April 21, 2024

How The Channel Tunnel Works

January 7, 2024

“Of course, you know that you Eeenglish invented modern people smuggling?”

In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams talks about the huge problems faced by European nations in combatting people smuggling:

Title page of a book covering the trial of seven smugglers for the murder of two revenue officers. In the preface the author says “I do assure the Public that I took down the facts in writing from the mouths of the witnesses, that I frequently conversed with the prisoners, both before and after condemnation; by which I had an opportunity of procuring those letters which are herein after inserted, and other intelligence of some secret transactions among them, which were never communicated to any other person.”

W.J. Smith, Smuggling and Smugglers in Sussex, 1749, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Prime Minister has nailed his colours to his mast and decided we should “stop the boats”. The slogan is everywhere. What Mr Sunak means is the vessels crossing the Channel laden with bedraggled folk seeking succour on the shores of Albion. I attended a conference recently to see how this was to be done. As the perpetrators are highly organised transnational criminals, the response must be a multi-national one. Delegates were given some historical context. Ours is not a unique era. Since pre-recorded history, mankind has been inclined to see the grass as always greener on the other side of the fence. Hollow out a log to cross a river, invade an island, a coastline, Troy, the Euphrates, the Tigris, the Nile. Anywhere, for trade, for adventure, for sanctuary. Leap the Channel by longship to escape overcrowding, poor crops, for plunder, to claim a crown.

However, we were reminded — for the conference was hosted by several coastal nations studying security and crime — that most of Europe’s maritime problems with criminality and smuggling, be it booze, tobacco, narcotics, fake branded goods, or people, involve rivers, not the open sea. An old friend from the Gendarmerie Maritime observed that the great rivers of the world are not only frontiers, but also highways; earlier versions of today’s motorways, as logistically familiar to the Romans as to our own times. Those long gaggles of barges which still shuffle along the Rhine or Danube are a happenstance of trade we Brits tend to overlook, as our canals and rivers have long been consigned to pleasure-boating.

Based in Messina, the gendarme’s opposite number from the Servizio navale of the Italian Carabinieri, wearing the most resplendent braid-laden uniform of anyone at our gathering, then fixed me with his gimlet eye. “Of course, you know that you Eeenglish invented modern people smuggling?” By this he went on to explain that many of the tricks of shifting people covertly through the Mediterranean, along the Dalmatian coast, by patrol boat about the Baltic, trawler braving the North Sea, MTB across the Channel, caïque over the Aegean, among the Ionian islands, and along the Adriatic, were devised by Britain’s Special Operation’s Executive (SOE) during the Second World War.

My Belgian and French friends observed that such smuggling had honourable roots. From 1789 and post-1917, many nations had aided middle class and aristocratic refugees to flee Revolutionary France and Russia. Subsequently, their descendants helped Jewish families quit the Third Reich. Others aided the British to move vast numbers of manpower by small boat in 1940 from Dunkirk, which emboldened fishermen to repeat the manoeuvre on a smaller scale to confound their German foes. Female Greek, Turkish and Croatian officers chipped in with their knowledge of various rat-lines established during World War Two to support partisans with personnel and weapons, and extract downed airmen, spies and important scientists. Post-war, as a Spanish policeman I knew from my days in Gibraltar observed, the same systems exported Nazi war criminals, and imported drugs and guns.

The modus operandi created in those heady days of derring-do were continued for spies during the Cold War, often by the same families, using the same craft. This applied as much to jaunts and japes up and down the Danube, Rhine, Meuse and Elbe waterways as it did to the open seas. Our Danish representative observed that “boat people” were a distraction. Their numbers were vastly overshadowed by far greater numbers of religious refugees and assorted shady characters, then and now, who used stolen genuine, or expertly forged papers; another legacy from the even more distant times that preceded World War Two. The man from Interpol revealed that today’s Italian and Albanian crime families have such advanced facilities for reproducing many of the world’s passports, ID cards, work permits and driving licences, that they will pass muster even at most European electronic frontier posts and airport controls. Our Albanian colonel shifted uncomfortably.

With the fall of the Iron Curtain, espionage went out of business and, casting about for new business, these latter-day privateers and licenced black marketeers started smuggling industrial quantities of things and people, to replace the nocturnal movement of atomic secrets by night over water. A dinghy full of people in mid-Ocean is merely the tip of a giant iceberg of organisation and logistics that started on 22 July 1940 by direct order of Winston Churchill, but has continued in various legal, semi-legal and illegal forms ever since.

October 23, 2023

Hero-worship of Admiral Nelson seen as (somewhat) harmful

On Saturday, Sir Humphrey noted the anniversary of Trafalgar and indicated that the Royal Navy’s idolization of Admiral Nelson somewhat obscures the rest of the Royal Navy’s historical role:

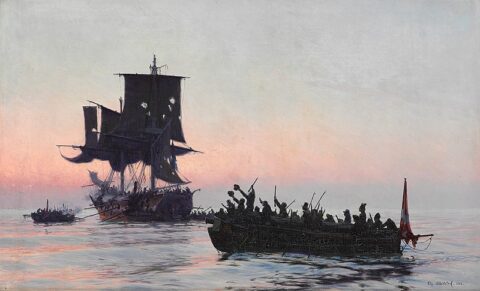

“Danish privateers intercepting an enemy vessel during the Napoleonic Wars”.

Oil painting by Christian Mølsted, 1888 from the Collection of the Museum of National History via Wikimedia Commons.

There is an argument, which the author has sympathy with, that the RN has perhaps idolised Nelson too much. That while he did much good, the adoration of him comes at the cost of forgetting countless other leaders and battles which have relevance to this day. This is not to denigrate or play down the impact of Trafalgar, but to ask whether we should be equally aware of other parts of Royal Navy history too. Understanding the Royal Navy of the late 18th and early 19th century can provide us with much to consider and learn from in looking at how to shape the Royal Navy of the early 21st century. If you look at the Royal Navy of today and of Nelson’s time (and throughout the Napoleonic Wars), a strong case can be made that although the technology is materially different, the missions, function, and capability that the RN offers to the Government of the day are little changed.

While we tend to fix attention mostly on the major battle of Trafalgar, the RN fulfilled a wide variety of different missions throughout the war. The fleet was responsible for blockading Europe, monitoring French movements, and providing timely intelligence on the activity of enemy fleets. Legions of smaller ships stood off hostile coasts, outside of engagement range, on lonely picket duties to track the foe. The Royal Navy also maintained forces capable of strategic blockades in locations like Gibraltar and the Skagerrak, relying on chokepoints to secure control of the sea.

The UK was a mercantile nation with a heavy reliance on trade, and with the land routes of Europe closed by Napoleon, the Merchant Navy was vital to victory. The Royal Navy played a key role in escorting ships in convoy, ensuring their protection from hostile forces and helping ensure vitally needed trade goods arrived in British ports. This included timber from colonies in North America, vital to building and repairing warships. Similarly British policy to defeat Napoleon relied on supporting continental land powers, and a steady flow of munitions and materiel were sent by sea, escorted by RN warships to Baltic ports to help support nations fighting France.

The Royal Navy maintained forces of small raiding craft to hold the French coast at risk throughout the wars, sending vessels to attack French coastal locations, capturing intelligence and tying down hundreds of French coastal artillery batteries and thousands of men who could have been deployed elsewhere to protect French soil. More widely the UK engaged in strategic raiding and blockade, for example operations in the Adriatic Campaign (1807-14) where a small number of British warships blockaded ports, conducted amphibious operations and engaged in surface combat with different foes. In the same vein the UK found itself targeted by Danish & Norwegian raiders too, who fought the so-called “Gunboat War” from 1807 to 14 against the UK, where many small scale actions between British brigs and small ships against gunboats in the Baltic. This often forgotten campaign saw violent clashes and victories on both sides with the sinking and capture of many RN vessels to protect convoy trade.

More widely the Royal Navy worked closely with the British Army in a variety of amphibious operations, providing ships to deploy and sustain the Army on campaign. There were a number of impressive amphibious failures, but also some successes too, particularly in the West Indies and Egypt, where working as part of a jointly integrated force, the Royal Navy provided fire support (and even operated Congreve land attack rockets for shore bombardment) as the British Army fought the French ashore. In the Peninsular War the RN was vital for ensuring the supply of Wellington’s forces and, where necessary evacuating them, such as during the retreat from Corunna.

June 4, 2023

D-Day Series: RCN and Operation Neptune

Valour Canada

Published 28 Dec 2015This video describes the Royal Canadian Navy’s (RCN) invaluable contributions to the invasion on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Operation Neptune was the name of the English Channel-crossing portion of the larger Normandy invasion (named Operation Overlord).

1. Overview (0:00)

Dawn. June 6, 1944. D-Day. Operation Overlord, the largest amphibious invasion in history, is about to begin. This is a description of the battlefield prior to the attack and also tells how the RCN played an important role both in the English Channel and along the French coast.2. Stop the U-boats (2:55)

Churchill said that the only thing that scared him during the war were the U-boats. This describes the problematic German U-boats and how the British and Canadian Navies (Operation Neptune) worked together to find, track, and destroy the underwater menace prior to D-Day.3. Clear the Mines (6:27)

“There is no doubt that the mine is our greatest obstacle to success” – British Admiral Bertram Ramsay. The size and effectiveness of the German minefield that guarded the D-Day beaches and how the Allied Navies worked together to prepare a route through which the invasion could occur.4. Cover the Beaches (9:49)

The Canadian Tribal-class destroyers played a significant role in eliminating the German Navy’s major surface warships’ threat to the invasion fleet. The RCN destroyer squadron and their mission of clearing the English Channel of German ships before, during, and after the invasion. A battle between the Canadian destroyers Haida and Huron and four German ships near the port of Brest on June 9 is discussed. Also covered are the two Canadian destroyers, Algonquin and Sioux, that were tasked with shore bombardment at Juno Beach.5. Land the Troops (13:01)

Shortly after dawn and following a forty-minute naval barrage at Juno Beach, the first Canadian soldiers came ashore. By noon, the beach was held by the Canadians and millions of tons of supplies were being brought ashore. This section describes the first waves of the invasion and the tanks, artillery, vehicles, and supplies that were soon to follow.

(more…)

March 16, 2023

History of the Royal Navy – Wooden Walls (1600-1805)

Ryan Doyle

Published 3 Mar 2013

(more…)

August 28, 2022

Jersey – Millennia of Maritime Defence Preserved

Drachinifel

Published 4 May 2022Today we take a look at the island of Jersey, part of the Channel Islands off the coast of France, to examine the many generations of maritime defence that have been built and upgraded there.

It’s an excellent place to visit! https://www.jersey.com/

(more…)

March 20, 2022

Canada Carries On — The Fighting Sea Fleas (1944)

PeriscopeFilm

Published 24 Dec 2012Support Our Channel: https://www.patreon.com/PeriscopeFilm

World War 2 propaganda film narrated by Lorne Greene about Canadian Motor Torpedo Boats crews and their actions. Shows life aboard Motor Torpedo Boats during the Battle of the Atlantic, fending off attacks by German U-Boats and commerce raiders. Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) was the name given to fast torpedo boats by the Royal Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy. The “Motor” in the formal designation, referring to the use of petrol engines, was to distinguish them from the majority of other naval craft that used steam turbines or reciprocating engines. Produced & Directed by Sydney Newman, and released in 1944.

This film is part of the Periscope Film LLC archive, one of the largest historic military, transportation, and aviation stock footage collections in the USA. Entirely film backed, this material is available for licensing in 24p HD. For more information visit http://www.PeriscopeFilm.com

December 8, 2021

What if the refugee flow was crossing the Channel the opposite way?

In The Critic, Joel Rodrigues considers what the media narrative would say if the constant stream of migrants from the EU to Britain was reversed, as all the major media outlets predicted would happen if Brexit went through:

This map shows the location of the Strait of Dover between England and France, and part of the English Channel and the North Sea. It also shows nearby towns such as Dover, Calais, and Dunkirk.

Image created by NormanEinstein via Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine “tent” cities on the Kent coast, similar to “the Jungle” that existed in Calais up until 2016. These camps are the type of camps that the Remain campaign (wrongly) warned would spring up if Britain voted to leave the EU, as part of their Project Fear campaign. The tent cities are full of migrants, hoping to reach the French coast and the “sunlit uplands” of the European Union.

The camps are filthy, riddled with violent crime, and it is here that people traffickers sell spaces on dinghies to cross the channel for thousands of pounds a ticket. The British police and immigration services are aware of undocumented people living in squalor in the camps, but largely do nothing.

Occasionally a camp is cleared to placate the locals, but it quickly springs up somewhere else. The British government make no effort to document, accommodate or process the migrants living in appalling conditions on its territory. Instead, it blames the “pull factor of the EU’s single market”, saying that many of these migrants have family in France and want to live in a French or German speaking society. A junior British minister suggests that the black market economies in the EU are also a pull factor, and that there are a “lack of safe asylum routes” into the EU.

People smugglers continue operating from the British coast, and the migrant camps expand. Dinghies are now launched daily from the UK towards the continent. Police are aware of the launches, but do nothing. The RNLI and Royal Navy escort these flimsy boats until they are in EU waters, despite their not being seaworthy. Thousands succeed in making the crossing.

Then, tragedy strikes when a boat sinks. Statements are released from the British and French governments lamenting the loss of life. Trying to find a solution, Emmanuel Macron writes a letter to Boris Johnson urging increased collaboration, with joint patrols if necessary, to prevent a repeat of the tragedy.

The British government issue a response claiming that the perfectly conciliatory letter is in fact unacceptable, a “threat to British sovereignty”, and that France is uninvited from crisis talks. British media later reports that in a meeting with some of his advisors, Boris Johnson branded Emmanuel Macron as “a clown in charge of a circus”.

Imagine the media commentary and narrative in the UK surrounding such a situation, especially post-Brexit.

“Migrants die fleeing racist, Brexit-ridden, plague island,” says an op-ed in the Guardian. The comments are largely agreed that Boris Johnson is personally responsible for each of their deaths.

“UK condemned as using migrants to destabilise the EU’s single market,” reports the BBC. Parallels are also drawn in The Times between Boris Johnson and Belarus’ Lukashenko. There are mass demonstrations outside Parliament as the crisis worsens.

One can imagine the EU Commission swiftly and publicly denouncing the UK and drawing up sanctions. The Labour party would likely call it a national scandal, and demand resignations, as well as accusing the government of taking a hardline stance as cynical electioneering.

I searched for public domain or Creative Commons images of the English Channel migrant crisis, but came up surprisingly empty, hence the generic map to illustrate this post. I had expected to be inundated with lots of heart-rending images of desperate refugees, but not this time…

November 5, 2021

QotD: The Dame of Sark

The death at ninety of Dame Sibyl Hathaway, the Dame of Sark, removed the only person in the British Isles whom I still wanted to meet. Unfortunately, she rejected all my advances. She was a model ruler for out times, forbidding not only cars and aircraft on her island, but also trade unions, taxation, female dogs, divorce, and most of the troublesome manifestations of our age. I had always hoped to persuade this admirable lady to take England under her rule when our parliamentary system finally disintegrates. Now she is dead I think I shall leave the country for a time — probably for a very long time. I can see no hope.

Auberon Waugh, Diary, 1974-07-25.

September 10, 2021

The Channel Dash / Operation Cerberus — How to win through refuge in audacity

Drachinifel

Published 9 Jan 2019Today we look at the Channel Dash, also known as one of the few times Hitler was right, the British were asleep and the Germans succeeded in spite of thinking they were all doomed. An operation made up purely of rolling natural 1’s and 20’s.

June 18, 2019

What Happened to the Giant Hovercraft SR-N4? – The Concorde of the Seas

Curious Droid

Published on 8 Sep 2017They were once known as the “Concorde of the Seas”: mighty flying boats that ferried their passengers with speed and style. Hovercraft was a symbol of national innovation and represented the future of transport in the 20th Century.

And yet, like the Concorde, the huge iconic “Mountbatten-class” hovercraft that once traversed the 22-mile English Channel from England to France carrying hundreds or passengers and cars are no longer with us.

So what happened to the giant hovercraft SN-R4?

Patreon : https://www.patreon.com/curiousdroid

Paypal.me : https://www.paypal.me/curiousdroidSponsors: Symon Hamer, Florian Hesse, Georgi Dobrev, Douglas Gustafson, Marcus Chiado, Mitchell Payce, Skalgrin, Jorn Karlsen, John Roscoe.

This episode’s shirt was the Trip Paisley Surf Retro by Madcap England and is available from http://www.atomretro.com/madcap_england

Get 10% discount with the code DROID10Presented By Paul Shillito

Written & Researched by Andy Munzer

Additional Material by Paul Shillito

Images and Footage : retepbleck, MAD Hovercraft, http://www.hovercraft-museum.org, Griffon Hoverwork, kentishmanvideo

Music by Mike Mullen, http://www.positrosmic.com

May 26, 2019

The Allied Clusterf**k in France – WW2 – 039 – May 25 1940

World War Two

Published on 25 May 2019While the massive invasion of the Benelux countries and France was going down last week, things were also developing on the fronts in Norway and China. But this week, the German beast is let loose. After breaking through its cage at Sedan last week, nothing seems strong enough to block its way to the English Channel. And if one thing becomes clear, it is that the Allied command structure and the way they communicate is one big smoking mess…

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Join our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN.

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: EastoryColorisations by Joram Appel, Spartacus Olsson and Norman Stewart.

Eastory’s channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEly…

Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.Sources:

FDR Presidential Library & Museum

National Portrait Gallery

IWM: H 9218, F 4484, F 4613, F 4578, F 4743б (F 4339

MUSÉE DES ETOILES

Nationaal Archief

Sound effect: LittleRobotSoundFactoryA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

April 15, 2015

Operation Sealion, wargamed by some of the original commanders

Strategy Page has a great summary of the German plan to invade Britain and the most likely outcome if the invasion had ever been attempted:

Operation Sealion, or, in the original German Unternehmen Seelöwe, is one of the most famous “what ifs” of the Twentieth Century.

On July 16, 1940, following the collapse of France, the Dunkerque evacuation, and the rejection of his peace overtures, Adolf Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 16, which initiated preparations for an invasion of Britain. At the time, it seemed to many that if Hitler had tried an offensive across the English Channel a defenseless Britain would inevitably fall. But was it so? What were Hitler’s chances?

In 1973 historian Paddy Griffith, just beginning his career as an instructor at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, decided to evaluate the chances of a successful German invasion of Britain by using a wargame.

Organization. Griffith’s wargame was much more than a board with a set of counters, a rule booklet, and some dice. It was a massive multiplayer game, which Griffith later wrote about in Sprawling Wargames. Based on traditional kriegsspiel methodology, the game involved several dozen players and umpires, all isolated from each other except by means of simulated signaling. Many of the players and umpires were veterans of the war from both sides. Among them were former wartime senior German officers such as Luftwaffe fighter Generalleutnant Adolf Galland and Kriegsmarine Vice Admiral Friedrich Ruge, as well as several men from both sides who had been lower ranking offices and later risen higher, including Christopher Foxley-Norris, who had commanded a fighter squadron during the Battle of Britain and rose to air chief marshal, Sir Edward Gueritz, a junior naval officer at the time who became a rear admiral, Heinz Trettner, who had served on the staff of the German airborne forces in 1940, rose to command a parachute division by war’s end, and later served as Inspector General of the post-war German air force, and Glyn Gilbert, a junior officer in one of the defending infantry battalions in 1941, who later rose to major general.

Each side was given the same forces, operational plans, and intelligence as it had in 1940. The game was based on the assumption that the Luftwaffe had still not won the battle for air supremacy over the Channel and southern England by the time the landings were scheduled to take place, in early September, which was in fact the case. The intelligence picture greatly favored the British, who had proven much better at securing information about the enemy’s plans and force than the Germans had on their own.

There’s even a mention of the (significant) Canadian contribution to the defence of Britain after Dunkirk:

The defending forces included the 1st Canadian Division (the most well-prepared division available, full strength and fully equipped, though without combat experience), plus the less-well prepared 2nd Canadian division and partial divisions from Australia and New Zealand.

Although I haven’t read Griffith’s book, my other readings on the subject align with the eventual outcome of the wargame:

Following the game the participants took part in a general analysis. Some interesting observations and conclusions were made. The British GHQ mobile reserve had not been engaged at all. In addition, casualties to the Royal Navy had been serious, but hardly devastating; of about 90 destroyers on hand, only five had been sunk and six seriously damaged, and only three of the three dozen cruisers had been lost, and three more heavily damaged.

Compare that to the actual Royal Navy losses during the evacuation of Crete — with little to no air support from the RAF, due to extreme distance from friendly airbases:

Attacks by German planes, mainly Ju-87s and Ju-88s, destroyed three British cruisers (HMS Gloucester, Fiji, and Calcutta) and three destroyers (HMS Kelly, Greyhound and Kashmir) between 22 May and 1 June. Italian bombers from 41 Gruppo sank one destroyer (Juno on 21 May and damaged another destroyer (Imperial) on 28 May beyond repair. The British were also forced to scuttle another destroyer (Hereward) on 29 May, that had been seriously damaged by German aircraft, and abandoned when Italian motor torpedo boats approached to deliver the coup de grâce.

Damage to the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable, the battleships HMS Warspite and Barham, the cruisers HMS Ajax, Dido, Orion, and HMAS Perth, the submarine HMS Rover, the destroyers HMS Kelvin and Nubian, kept these ships out of action for months. While at anchor in Suda Bay, northern Crete, the heavy cruiser HMS York was badly damaged by Italian explosive motor boats and beached on 26 March 1941. She was later wrecked by demolition charges and abandoned when Crete was evacuated in May. By 1 June the effective eastern Mediterranean strength of the Royal Navy had been reduced to two battleships and three cruisers to oppose the four battleships and eleven cruisers of the Italian Navy

And back to the Operation Sealion summary from Strategy Page:

All participants, German as well as British, agreed that the outcome was an accurate assessment of the probable result of an actual invasion.

Oddly, the Sandhurst wargame was designed on the basis of inaccurate information. Some time after the game, additional hitherto secret documents came to light, which revealed that the Germans probably had even less chance of success than they did in game. At the time the game was designed, the true extent of British “stay behind” forces, intended to conduct guerrilla operations in the rear of the invasion forces, and the sheer scale of defensive installations that had been erected across southern England in anticipation of an invasion were still classified; there were some 28,000 pill boxes, coastal batteries, strong points, blockhouses, anti-aircraft sites, and some other installations.

So assuming Hitler had for a time been serious about invading England, his decision to call it off was probably wise.

September 28, 2014

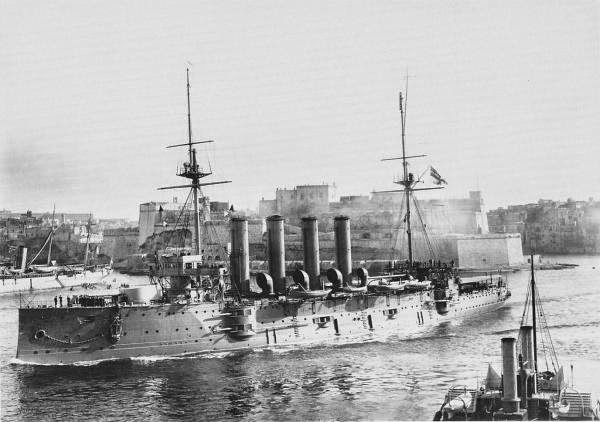

The “Live Bait Squadron” in the Broad Fourteens

Antoine Vanner recounts the tragic story of the sinking of three Royal Navy armoured cruisers (HMS Aboukir, HMS Hogue, and HMS Cressy) early in the First World War:

Despite this “wake up call” regarding vulnerability of warships at low speed the Royal Navy initiated a patrol of the northern entrance of the English Channel with five obsolete Cressy class armoured cruisers. This group was known as “Cruiser Force C” and the patrol area they were assigned to was in the shallow waters off the Dutch coast known as the “Broad Fourteens”. The logic of maintaining a patrol in the area was unassailable as a fast German raiding force of destroyers could wreak havoc on British maritime supply lines between the English Coast and Northern France should they enter the Channel. Though destroyers and light cruisers would have been more suited to the task it was believed that destroyers would be unable to maintain the patrol in bad weather and insufficient modern light cruisers were available. The solution was to deploy old armoured cruisers which had at least got the necessary station-keeping capability. This was perhaps their only positive attribute.

The vulnerability of these cruisers was recognised by many senior officers, not only because of their obsolescence but because of their manning. Taken hastily from reserve – which meant they had been unmanned and poorly, if at all, maintained – on outbreak of war they were quickly overhauled and put back in service. Originally capable of 21 knots they now found it hard to make 15. Crews were in short supply, leading the ships to be manned by reservists, many middle-aged, many of them pensioners, who had not previously served or exercised together as units. In addition, nine naval cadets, some as young as 15, were allocated to each ship, being taken directly from the Royal Naval College. The general view of Cruiser Force C’s fighting potential was summed up in the nickname it quickly acquired – the “Live Bait Squadron”.

Britain’s armoured cruisers can be fairly described as the most unsuccessful and unfortunate type of warship ever employed by the Royal Navy. The 34 vessels of this type that were in service at the outbreak of war had entered service between 1902 and 1908 – they were not old ships. Of these 34, a total of 13 were to be lost in the next four years. Intended to form part of the battle fleet, they had been rendered obsolete by the advent of the almost equally-disastrous battle-cruiser concept. The earlier classes – the six ships of the Cressy class being the oldest – had very limited offensive capability, especially in rough weather. They were large – and expensive – ships and they needed large crews.

[…]

At dawn on September 22nd U-9 surfaced to find the storm over, the sea calm but for a slow swell. Smoke was seen on the horizon and the U-9’s engines were immediately shut down to get rid of their exhaust plume. A quick appraisal led Weddingen to order diving but he continues to observe through his periscope. Three vessels were approaching – the Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue – and Weddingen steered on his electric motors towards the central vessel, Aboukir.

Undetected, U-9 came within 600 yards of Aboukir’s port bow before firing a torpedo. As this was still running Weddingen took his craft down to 50 feet, then heard “a dull thud, followed by a shrill-toned crash”. Cheering erupted on U-9.

October 11, 2012

French fishing fleet dabbles in piracy, maritime intimidation

The BBC reports on a recent incident between British and French fishing vessels:

Fishermen are calling for Royal Navy protection after claims they were attacked by French vessels.

Kevin Lochrane, from East Sussex, said he was surrounded by seven or eights boats in international waters 15 miles off Caen in a dispute over scallops.

One Scottish fisherman, Andy Scott, said he feared for his crew’s safety during the incident.

Other crewmen said they were also surrounded by the French fishermen, who they said tried to damage their gear.