TimeGhost History

Published 5 Mar 20251946 sees the world teetering on the brink of a new global conflict. George Kennan’s long telegram outlines Moscow’s fanatical drive against the capitalist West, while our panel covers escalating espionage, strategic disputes over Turkey, and the emerging ideological battle between the U.S. and the USSR. Tune in as we break down the news shaping the dawn of the Cold War.

(more…)

March 6, 2025

The Iron Curtain Descends – W2W 10 – News of 1946

March 3, 2025

Europe’s Imperial Giants: On the Brink of Collapse? – W2W 09 Q4 1946

TimeGhost History

Published 2 Mar 2025In 1946, Britain, France, and the Netherlands fight to regain control over shattered colonies — from Indonesia’s revolt to Vietnam’s war with France. Meanwhile, the U.S. and USSR maneuver to shape these emerging nations for their own global interests. Will independence spark true liberation, or will it simply swap one master for another?

(more…)

February 23, 2025

How WW2 Changed Espionage Forever

World War Two

Published 22 Feb 2025In their struggle to defeat German and Japanese espionage efforts, the Allied intelligence agencies of the KGB, CIA, MI6 and DGSE are all transformed into modern, global, espionage forces. But even as East and West work together to defeat the Axis, they are fighting the first underground battles of a new Cold War against one another.

(more…)

January 23, 2025

The Google of the early modern era

Ted Gioia compares the modern market power of the Google behemoth to the only commercial enterprise in human history to control half of the world’s trade — Britain’s “John Company”, or formally, the East India Company which lasted over 250 years growing from an also-ran to Dutch and Portuguese EICs to the biggest ever to sail the seas:

No business ever matched the power of the East India Company. It dominated global trade routes, and used that power to control entire nations. Yet it eventually collapsed — ruined by the consequences of its own extreme ambitions.

Anybody who wants to understand how big businesses destroy themselves through greed and overreaching needs to know this case study. And that’s especially true right now — because huge web platforms are trying to do the exact same thing in the digital economy that the East India Company did in the real world.

Google is the closest thing I’ve ever seen to the East India Company. And it will encounter the exact same problems, and perhaps meet the same fate.

The concept is simple. If you control how people connect to the economy, you have enormous power over them.

You don’t even need to run factories or set up retail stores. You don’t need to manufacture anything, or create any object with intrinsic value.

You just control the links between buyers and sellers — and then you squeeze them as hard as you can.

That’s why the East India Company focused on trade routes. They were the hyperlinks of that era.

So it needed ships the way Google needs servers.

The seeds for this rapacious business were planted when the British captured a huge Portuguese ship in 1592. The boat, called the Madre de Deus, was three times larger than anything the Brits had ever built.

But it was NOT a military vessel. The Portuguese ship was filled with cargo.

The sailors couldn’t believe what they had captured. They found chests of gold and silver coins, diamond-set jewelry, pearls as big as your thumb, all sorts of silks and tapestries, and 15 tons of ebony.

The spices alone weighed a staggering 50 tons — cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, pepper, and other magical substances rarely seen in British kitchens.

This one cargo ship represented as much wealth as half of the entire English treasury.

And it raised an obvious question. Why should the English worry about military ships — or anything else, really — when you could make so much money trading all this stuff?

Not long after, a group of merchants and explorers started hatching plans to launch a trading company — and finally received a charter from Queen Elizabeth in 1600.

The East India Company was now a reality, but it needed to play catchup. The Dutch and the Portuguese were already established in the merchant shipping business.

By 1603, the East India Company had three ships. A decade later that had grown to eight. But the bigger it got, the more ambitious it became.

The rates of return were enormous — an average of 138% on the first dozen voyages. So the management was obsessed with expanding as rapidly as possible.

They call it scalability nowadays.

But even if they dominated and oppressed like bullies, these corporate bosses still craved a veneer of respectability and legitimacy — just like Google’s CEO at the innauguration yesterday. So the company got a Coat of Arms, playacting as if it were a royal family or noble clan.

As a royally chartered company, I believe the EIC was automatically entitled to create and use a coat of arms. Here’s the original from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I:

October 17, 2024

Historian Reacts to Canada and the Scheldt Campaign

OTD Military History

Published 8 Oct 2024My reaction to the @LEGIONMAGAZINE’s video on the Battle of the Scheldt. This campaign was one of the toughest ever fought by Canada in World War 2.

Canada and the Scheldt Campaign from Legion Magazine

• Canada and the Scheldt Campaign | Nar…

(more…)

July 15, 2024

Revisiting the “official” story of Srebrenica

Niccolo Soldo’s weekly roundup includes a look at the differences between the story the media told us about the Srebrenica massacre and what has come to light since then:

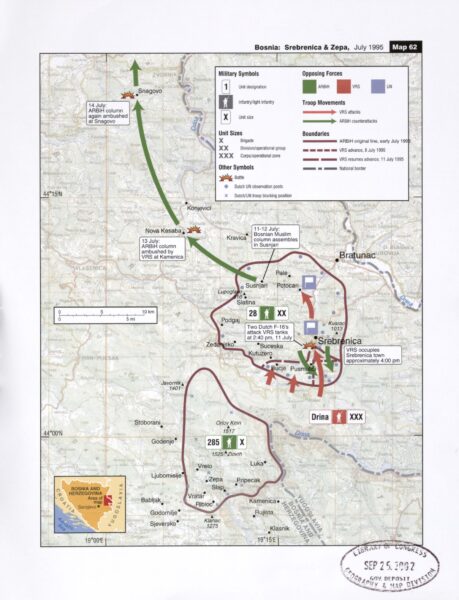

Map of military operations on July, 1995 against the town of Srebrenica.

Map 61 from Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict; Map Case (2002) via Wikimedia Commons.

29 years ago this week, Bosnian Serb forces of the VRS managed to seize the town of Srebrenica in Eastern Bosnia, on the border with Serbia. A massacre of Bosnian Muslim males ensued shortly thereafter, and the narrative of genocide sprung forth quickly from it, giving cause to NATO’s intervention in that conflict.

Did a massacre occur? Certainly. Some 2,000 Bosnian Muslim males were summarily executed by Bosnian Serb forces around Srebrenica shortly after the UN-designated “safe haven” fell to the Serbs. Some 8,000 Bosnian Muslims lost their lives in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Srebrenica, but the narrative of “genocide” whereby all 8,000 were executed is simply not true as per John Schindler, the then-Technical Director for the Balkans Division of the NSA:

Twenty-nine years ago today, the Bosnian Serb Army captured Srebrenica, an isolated town in Bosnia’s east that was jam-packed with Bosnian Muslims, most of them refugees. This small offensive, involving only a couple of battalions of Bosnian Serb troops, soon became the biggest story in the world. What happened around Srebrenica in mid-July 1995 permanently changed the West’s approach to war-making and diplomacy.

The essential facts of the Srebrenica massacre are not in dispute. The town was a United Nations “safe area” but U.N. peacekeepers there, an understrength Dutch battalion, failed to protect anyone. Over the week following Srebrenica’s quick fall, some 8,000 Bosnian Muslims, almost all male, a mix of civilians and military personnel, were killed by Bosnian Serb forces. About 2,000 disarmed Bosnian Muslim prisoners of war were executed soon after the town’s capture. The rest died in the days that followed, all over eastern Bosnia.

As the world learned the extent of the massacre, by far the biggest atrocity in the Bosnian War that had raged since the spring of 1992, Western anger mounted. Six weeks later, President Bill Clinton ordered the Pentagon to bomb the Bosnian Serbs in Operation Deliberate Force, the first major military action in NATO’s history. By the year’s end, the war was concluded by American-led diplomacy.

Here are Schindler’s conclusions:

That for three years, Srebrenica, supposedly a U.N. “safe area,” served as a staging base for Bosnian Muslim attacks into Serb territory. The Muslim military’s 28th Division regularly attacked out of Srebrenica. Bosnian Serbs claim they lost over 3,000 people, civilian and military, to those attacks.

That the Bosnian Muslim commander at Srebrenica, Naser Oric, was a thug who tortured and killed Serb civilians (he showed Western journalists footage of his troops decapitating Serb prisoners), as well as fellow Muslims he disliked. Mysteriously, Oric fled Srebrenica three months before the town’s fall, leaving his troops to die.

That most of the Bosnian Muslim dead, some three-quarters of them, died not at Srebrenica but during an attempted breakout by troops of the 28th Division to reach their own lines around Tuzla. They showed little communications discipline, and Bosnian Serb forces called down their artillery on them, columns of Muslim military and civilians together, slaughtering them. This doesn’t meet any standard definition of genocide.

That the Muslims were flying weapons into the “safe area” by helicopter in the months before the Bosnian Serb offensive. (Controversially, the Pentagon knew this was happening but pretended it didn’t.) The Serbs repeatedly protested to the U.N. about this violation, to no avail. This was the reason for the offensive to take the town.

There’s also convincing evidence that the Muslim leadership in Sarajevo knew Srebrenica would be attacked and allowed it to fall. Their leader, Alija Izetbegovic, stated that if Srebrenica fell, the Serbs would massacre Muslims as payback, and America would intervene on the Muslim side in the war. He was right.

Some of you may not like what John has to say here about Gaza and how it relates to Srebrenica:

This isn’t merely a historical matter. What happened in Bosnia is being repeated today in Gaza. Western journalists uncritically accept Muslim claims about war crimes and “genocide” to smear a Western state that’s at war with radical Islam.

Here the strange ideological affinity between jihadists and the Western Left plays a role, as it did during the Bosnian War as well. No claims of war crimes, which possess great political value on the world stage, should be accepted without independent confirmation. Srebrenica should have taught Western elites this essential truth, but it didn’t.

On a personal note, I like to bring up Srebrenica to Serbs as an example of how media shapes narratives that are often very remote from the truth in the hope that they understand what I am saying in a wider context.

Fun fact: Srebrenica translates into “Silverton”, as it was a significant silver mining town during the late Medieval era, with imported Saxons running the show.

June 30, 2024

The medieval salt trade in the Baltic

In the long-awaited third part of his series on salt, Anton Howes discusses how the extremely low salt level of water in the Baltic Sea helped create a vast salt trade dominated by the merchant cities of the Hanseatic League:

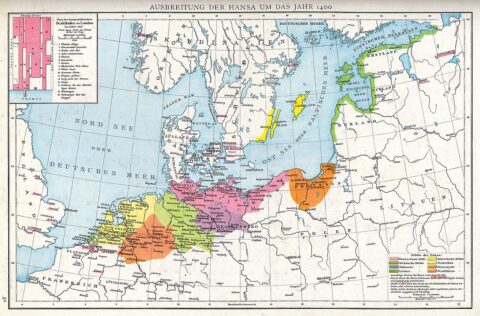

The extent of the Hanseatic League in 1400.

Plate 28 of Professor G. Droysen’s Allgemeiner Historischer Handatlas, published by R. Andrée, 1886, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s difficult to appreciate salt’s historical significance because it’s now so abundant. Societies used to worry about salt supplies — for preparing and preserving food — as a matter of basic survival. Now we use the vast majority of it for making chemicals or chucking on our roads to keep them from getting icy, while many salt-making plants don’t even operate at full capacity. Yet the story of how we came to achieve salt superabundance is a long and complicated one.

In Part I of this series we looked at salt as a kind of general-purpose technology for the improvement of food, as well as a major revenue-raiser for empires — especially when salt-producing coastal areas could dominate salt-less places inland. In Part II we then looked at a couple of places that were all the more interesting for being both coastal and remarkably salt-less: the coast of Bengal and the Baltic Sea. One was to be exploited by the English East India Company, which needlessly propped up a Bengalese salt industry at great human cost. The other, however, was to prove a more contested prize — and ultimately the place that catalysed the emergence of salt superabundance.

It’s worth a brief recap of where we left the Baltic. Whereas the ocean is on average 3.5% salt, along the Baltic coast it’s at just 0.3% or lower, which would require about twelve times as much time and fuel to produce a given quantity of salt. Although there are a few salt springs near the coast, they were nowhere near large enough to supply the whole region. So from the thirteenth century the Baltic’s salt largely came from the inland salt springs at Lüneburg, supplied via the cities of Lübeck and Hamburg downstream. These two cities had a common interest against the kingdom of Denmark, which controlled the straits between the North and Baltic seas, and created a coalition of trading cities that came to be known as the Hanseatic League. The League resoundingly defeated the Danes in the 1360s and 1430s so that their trade in salt — and the fish they preserved with it — could remain free.

But Lüneburg salt — and by extension the League itself — was soon to face competition.

Lüneburg could simply not keep up with the growth of Baltic demand, as the region’s population became larger and wealthier. And so more and more salt had to come from farther afield, from the Bay of Biscay off France’s western coast, as well as from Setúbal in Portugal and from southern Spain.1 This “bay salt” — originally referring to just the Bay of Bourgneuf, but then extended to the entire Bay of Biscay, and often to all Atlantic solar-evaporated salt — was made by the sun and the wind slowly evaporated the seawater from a series of shallow coastal pools, with the salt forming in coarse, large-grained pieces that were skimmed off the top. Bay salt, however, inevitably ended up mixed with some of the sand and dirt from the bottoms of the pools in which it was held, while the seawater was never filtered, meaning that the salt was often brown, green, grey or black depending on the skill of the person doing the skimming — only the most skilled could create a bay salt that was white. And it often still contained lots of other chemicals found in seawater, like magnesium chloride and sulphate, calcium carbonate and sulphate, potassium chloride and so on, known as bitterns.2

Bay or “black” salt, made with the heat of the sun, was thus of a lower quality than the white salt boiled and refined from inland salt springs or mined as rock. Its dirt discoloured and adulterated food. Its large grains meant it dissolved slowly and unevenly, slowing the rate at which it started to penetrate and preserve the meat and fish — an especially big problem in warmer climates where flesh spoiled quickly. And its bitterns gave it a bitter, gall taste, affecting the texture of the flesh too. Bay salt, thanks to the bitterns, would “draw forth oil and moisture, leading to dryness and hardness”, as well as consuming “the goodness or nutrimental part of the meat, as moisture, gravy, etc.”3 The resulting meat or fish was often left shrunken and tough, while bitterns also slowed the rate at which salt penetrated them too. Bay-salted meat or fish could often end up rotten inside.

But for all these downsides, bay salt required little labour and no fuel. Its main advantage was that it was extremely cheap — as little as half the price of white Lüneburg salt in the Baltic, despite having to be brought from so much farther away.4 Its taste and colour made it unsuitable for use in butter, cheese, or on the table, which was largely reserved for the more expensive white salts. But bay salt’s downsides in terms of preserving meat and fish could be partially offset by simply applying it in excessive quantities — every three barrels of herring, for example, required about a barrel of bay salt to be properly preserved.5

By 1400, Hanseatic merchants were importing bay salt to the Baltic in large and growing quantities, quickly outgrowing the traditional supplies. No other commodity was as necessary or popular: over 70% of the ships arriving to Reval (modern-day Tallinn in Estonia) in the late fifteenth century carried salt, most of it from France. But Hanseatic ships alone proved insufficient to meet the demand. The Danes, Swedes, and even the Hanseatic towns of the eastern Baltic, having so long been under the thumb of Lübeck’s monopoly over salt from Lüneburg, were increasingly happy to accept bay salt brought by ships from the Low Countries — modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands. Indeed, when these interloping Dutch ships were attacked by Lübeck in 1438, most of the rest of the Hanseatic League refused Lübeck’s call to arms. When even the Hanseatic-installed king of Denmark sided with the Dutch as well, Lübeck decided to back down and save face. The 1441 peace treaty allowed the Dutch into the Baltic on equal terms.6 Hanseatic hegemony in the Baltic was officially over.

The Dutch, by the 1440s, had thus gained a share of the carrying trade, exchanging Atlantic bay salt for the Baltic’s grain, timber, and various naval stores like hemp for rope and pitch for caulking. But this was just the beginning.

1. Philippe Dollinger, The German Hansa, trans. D. S. Ault and S. H. Steinberg, The Emergence of International Business, 1200-1800 (Macmillan and Co Ltd, 1970), pp.219-220, 253-4.

2. L. Gittins, “Salt, Salt Making, and the Rise of Cheshire”, Transactions of the Newcomen Society 75, no. 1 (January 2005), pp.139–59; L. G. M. Bass-Becking, “Historical Notes on Salt and Salt-Manufacture”, The Scientific Monthly 32, no. 5 (1931), pp.434–46; A. R. Bridbury, England and the Salt Trade in the Later Middle Ages (Clarendon Press, 1955), pp.46-52. Incidentally, some historians, like Jonathan I. Israel, Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585-1740 (Clarendon Press, 1989) p.223, note occasional reports of French bay salt having been worse than the Portuguese or Spanish due to its high magnesium content, “which imparted an unattractive, blackish colour”. This must be based on a misunderstanding, however, as the salts would have been identical other than in terms of the amount of dirt taken up with the salt from the pans. At certain points in the seventeenth century the French workers skimming the salt must simply have been relatively careless compared to those of Iberia.

3. John Collins, Salt and fishery a discourse thereof (1682), pp.17, 54-5, 66-8.

4. Bridbury, pp.94-7 for estimates.

5. Karl-Gustaf Hildebrand, “Salt and Cloth in Swedish Economic History”, Scandinavian Economic History Review 2, no. 2 (1 July 1954), pp.81, 86, 91.

6. For this section see: Dollinger, pp.194-5, 201, 236, 254, 300.

June 26, 2024

Why the Allies Lost The Battle of France

Real Time History

Published Mar 1, 2024In May 1940, Nazi Germany attacks in the West. The Allied armies of France, Britain, Belgium, and the Netherlands have more men, guns, and tanks than the Germans do – and the French army is considered the best in the world. But in just six weeks, German forces shock the world and smash the Allies. So how did Germany win so convincingly, so fast?

(more…)

June 16, 2024

Mao Tightens His Grip – WW2 – Week 303 – June 15th, 1945

World War Two

Published 15 Jun 2024After several weeks of the Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong’s power has consolidated to the point that it is absolute. All pledge loyalty Mao, and his infallibility shall not be questioned. Meanwhile the war goes on in the field with Australian landings on Brunei, continuing fighting on Okinawa, and the last part of Europe — in the Netherlands — liberated from Axis control.

(more…)

June 14, 2024

QotD: European “megacorporations” in the east

The great (and terrible) chartered trading companies offer a more promising historical parallel for the megacorporation, with much larger scope. The largest of these were the British East India Company (EIC, 1600-1874) and the Dutch East India Company (the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC, 1594-1800). The EIC at one point accounted for something close to half of the the world’s trade and the VOC at points had total or near-total monopolies on the trade of important and valuable spices. Both companies were absolutely massive and exercised direct, state-like authority over territory and people.

And the structure of these massive trading companies mirrors some of the elements of a megacorp. While both companies were, in theory, shipping companies, in practice they were massive vertically integrated conglomerates. Conquering the production areas (particularly India for the EIC and Java for the VOC), they essentially controlled the production chain from start to finish. That complete vertical integration meant that the companies also had to supply employees and colonial subjects, which in turn meant controlling trade and production in everything from food and clothes to weapons. Both companies had their own armies and fleets (the EIC boasted more than 25,000 company soldiers at its height, the VOC more than 10,000) and controlled and administered territory.

In short, they were the colonial Dutch and British governments for many millions of colonial subjects. For the people living in territory dominated by these companies, they really would have resembled the megacorps of speculative fiction, operating with effectively impunity and using their vast profits to field armies and navies capable of defeating local states and compelling them to follow the interests of the company (which remained profit-oriented).

(I feel the need to stop and note that “company rule” in India and even more so in the Dutch East Indies was brutally exploitative, living up to – and in many cases quite surpassing – the normal dystopian billing of science fiction megacorporations. At the same time, it seems equally worth noting that the shift to direct colonial rule by the state was not always much better.)

So in one sense, the speculative fiction megacorp has already existed, but in the other, the limits of these historical entities are informative too. First, it seems relevant that none of these companies were creatures of the markets, rather, they were created by state action – they were chartered companies, state monopolies, or both. These massive imperial trading companies (of which the EIC and VOC were the most successful, but not the only ones) were all created by their respective governments, armed with substantial privileges and typically given exclusive rights to certain trade – they were state-sanctioned monopolies (echoes of this also in the Japanese Zaibatsu state-sanctioned vertical monopolies; note that the Roman publicani [tax-farming “companies” of the middle and late Republic] were also state-sanctioned monopolies) whose monopolies were backed by state power to the point that their states (that is, Britain, the Dutch Republic, France and so on) would and did go to war to protect the trading rights of their monopoly trading companies.

Second, these megacorporations, far from being in a position to usurp the states that formed them (as fictional megacorporations often do), turn out to be extremely vulnerable to those states. The EIC was effectively nationalized by an act of parliament in 1858 (after the Indian Mutiny of 1857 discredited company rule in the eyes of the British government) and disbanded in 1874. The VOC was likewise nationalized by its parent government in 1796 and then dissolved in 1799. No effort was made by either company to resist being disbanded with any sort of force; it would have been a pointless gesture in any case. While the resources of the EIC were vast, the military capabilities of the British Empire were far greater. Moreover, the companies simply didn’t have the legitimacy to operate absent their state backing.

This is of course also true for the not-quite-megacorporations, like the great trusts of America’s gilded age (Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, etc.), or the Japanese zaibatsu or even modern super-sized corporate entities. Of the 10 largest companies in the world, four are straight up state-owned enterprises. Even for the private modern massive company, by and large when they try to fight their “home” state, they lose, or at least are badly damaged without seriously inconveniencing the far greater power of the state (just ask AT&T or Microsoft).

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: January 1, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-01.

May 26, 2024

The Last Battles in Europe – WW2 – Week 300 – May 25, 1945

World War Two

Published 25 May 2024This week, the fighting in Europe finally comes to an end and the Allies round up more leading Nazis including Heinrich Himmler and Karl Dönitz. In Asia, the fighting continues on Okinawa even as the Japanese start pulling back. The Australians continue fighting on Tarakan, and the Chinese are victorious in western Hunan.

00:00 Intro

01:45 Fighting In Europe Ends

04:30 Notes From Europe

06:57 Japanese Begin To Withdraw On Okinawa

12:41 The Battle Of Tarakan Island

14:35 Chinese Victory In Western Hunan

18:51 Conclusion

(more…)

May 5, 2024

Allied Victory in Berlin, Italy, and Burma! – WW2 – Week 297 – May 4, 1945

World War Two

Published 4 May 2024So much goes on this week, and this is the longest episode of the war by like 15 minutes. But there’s so much to cover! The Battle of Berlin ends; the war in Italy ends; the war in Burma ends- well, it ends officially, though there are still tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers scattered around Burma. And there’s a whole lot more to these stores and a whole lot more stories this week in the war. You can’t miss this one.

01:27 The End of the War in Italy

03:40 Western Allied Advances

07:02 Relief Operations in the Netherlands

15:45 Hitler’s Death and the Surrender of Berlin

24:20 Walther Wenck’s Retreat

28:00 The Polish Situation

31:09 What About Prague?

32:44 The End of the Burma Campaign

36:04 THE FIGHT FOR TARAKAN ISLAND BEGINS

37:24 Okinawa

40:11 Other Notes

41:04 Summary

41:43 Conclusion

(more…)

April 11, 2024

QotD: North America will never be a “bicycle” culture

Regarding bicycles, they, like motorcycles, have long since transformed from “a means of locomotion” to “a lifestyle”. Note that I’m only talking about AINO here. Everyone has heard that “more bicycles than people in the Netherlands” factoid, and Euros do seem to love them some bikes, but I haven’t spent enough time over there to say much about it. Here in the Former America, though, anyone who rides a bicycle past age 16 falls into one of two broad groups: 1) they’re nature lovers who want to be out in the countryside but for various reasons can’t take up hiking, or 2) they’re preening, posturing, virtue-signaling, passive-aggressive assholes. The latter outnumber the former about 5,000 to 1.

I’m deliberately discounting bicycles as a means of locomotion, you’ll notice, because look: America is a car society. Our cities are designed for cars. Indeed, given the vast distances involved over here, cars are what make our lifestyle possible. Europeans who haven’t been here, or who only visit the big tourist pits like NYC and LA, don’t get this. Even if you’ve seen the maps, it doesn’t really register until you experience it. I’m just guessing here, for purposes of explanation, but it really does seem to be the case that if it were possible to hop in your car and drive two hours due east from downtown Paris, you’d pass through three or four countries. There are lots of American cities where, if it were possible to hop in your car and drive two hours straight from downtown, you’d still be in that same city. The continental US is just mind-bogglingly huge; only Russians and maybe Australians share our mental maps. When you’ve got daily commutes that run an hour, hour and a half on freeways, setting anything up with bicycles in mind is just ludicrous.

Severian, “Cars, Bikes, Motorcycles”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-07-25.

March 28, 2024

Why European farmers are revolting

spiked

Published Mar 27, 2024Europe’s farmers are rising up – and the elites are terrified. From the Netherlands to Germany to Ireland, farmers are taking to the streets, parking their tractors on the establishment’s lawn, spraying buildings with manure and bringing life to a standstill. The reason? Because unhinged green regulations, dreamt up by European Union bureaucrats, are immiserating them. In this spiked video polemic, Fraser Myers explores the roots of the farmers’ revolt across the continent – and explains why it must succeed. Watch, share and let us know what you think in the comments.

Support spiked:

https://www.spiked-online.com/support/

Sign up to spiked‘s newsletters: https://www.spiked-online.com/newslet…

Check out spiked‘s shop: https://www.spiked-online.com/shop/

February 25, 2024

Battleships – Ruling the Waves Across the 7 Seas – Sabaton History 124 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published Nov 16, 2023They were as much symbols of national pride as they were mighty weapons of war, but they were indeed MIGHTY. Dreadnoughts, battleships, super battleships — Sabaton has covered them in songs more than once, and today we dive into the battleship craze of the early 20th century: the Age of the Battleship!

(more…)