Ed West believes we’re suffering so many social ailments because we’re social creatures, evolutionarily speaking, and modern society has reduced or eliminated so many traditional community social gatherings — made far, far worse by arbitrary lockdown rules and harsh enforcement during the Wuhan Coronavirus panicdemic. He’s talking specifically about Britain and Europe, but the same definitely applies here in North America:

“Procession for Corpus Christi” attributed to Master of James IV of Scotland (Flemish, before 1465 – about 1541), illuminator.

Original illumination in the Getty Center Collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week, for example, most of continental Europe got a holiday to mark Corpus Christi, once a huge event in England but killed off by the Reformation. Why can’t we have a holiday too? It was 27 degrees in London last Thursday — it would have been great.

We’re all aware, on some subconscious level, that there is a need for communal feasts and holidays, and in some ways the idea of a June procession to celebrate the official religion has made a comeback with Pride. The feast-shaped hole in our lives is why, from time to time, the great and the good come up with very boring ideas for substitutes feasts, the latest being “Celebration Day”. The idea is for “one day in the year when we can all take a pause in our busy lives to reflect, remember and celebrate the lives of people no longer here”. You mean, like the feast of All Saints’ and All Souls’, which again was a huge part of our calendar once and is still marked in Catholic countries? Like that one?

[…]

Contrary to the fashionable Noughties takes about the evils of supernatural belief, religion has huge psychological benefits. There is a vast array of evidence showing that attending religious ceremonies increases dopamine responses in the brain. Overcoming our fear of death is not even the key part; it is meeting other people and taking part in a common ritual, which has huge benefits, including reduced risk of suicide or addiction. Religious attendance is “associated with lower psychological distress” and “related to higher well-being”.

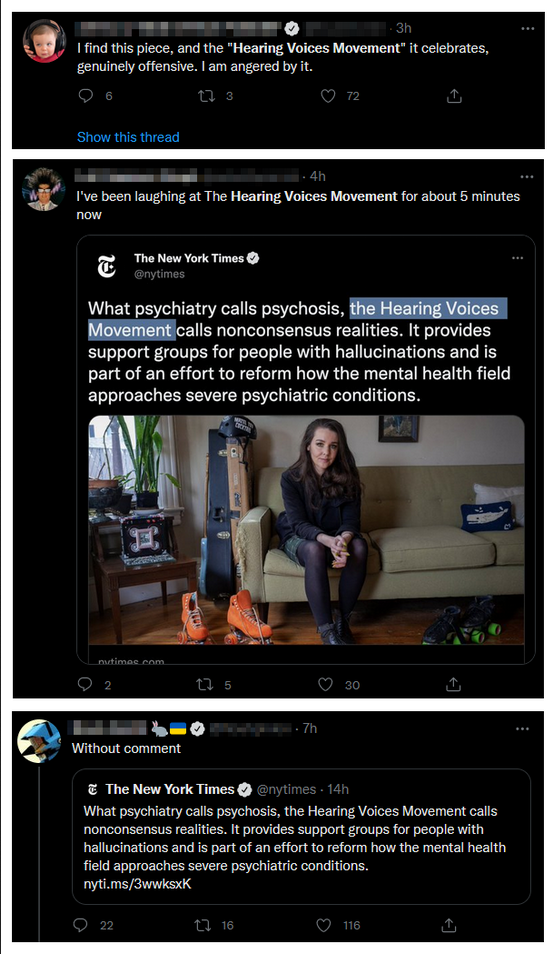

Modernity, diet and substance abuse may have slightly increased rates of extreme mental illness such as schizophrenia, while social media has allowed people with personality disorders to become prevalent, especially in politics. But most of the “mental health crisis” is just loneliness. People attend fewer communal events because of the decline of religion, they see other people less regularly and they have fewer friends — of course they’re unhappy! Humans are not just social mammals, we are ultra-social by the standards of other species; that’s why we need common rituals and why we’re chasing that religious feeling everywhere and can’t find it. It is why, as Madeline Grant wrote in the Telegraph this week, that as well as progressive institutions adopting religious-type feasts, even exercise classes increasingly resemble Mass.

Lockdown, traumatic though it was, was merely an extreme version of the trend towards solitude already underway (with working from home, online shopping and various other lockdown activities on the rise before 2020). Most traditional societies would consider our everyday lives in non-Covid times to be a form of lockdown, with historically very unusual levels of isolation. That is why the extreme loneliness of lockdown gave rise to ersatz rituals such as Clap for Carers.

Yet you just can’t beat the real thing. As Parker wrote at the time, ritual decline was a real sadness in our lives: “From the Middle Ages until the first half of the 20th century, Whitsun and the week that followed was the chief summer holiday of the year in Britain. It was a time for all kinds of communal merry-making, varying over the centuries but consistent in spirit: the season for feasts and fairs, dancing and drinking, school and church processions, and generally having a good time.”