One of the interesting things about being a participant-observer anthropologist, as I am, is that you often develop implicit knowledge that doesn’t become explicit until someone challenges you on it. The seed of this post was on a recent comment thread where I was challenged to specify the difference between a geek and a hacker. And I found that I knew the answer. Geeks are consumers of culture; hackers are producers.

Thus, one doesn’t expect a “gaming geek” or a “computer geek” or a “physics geek” to actually produce games or software or original physics – but a “computer hacker” is expected to produce software, or (less commonly) hardware customizations or homebrewing. I cannot attest to the use of the terms “gaming hacker” or “physics hacker”, but I am as certain as of what I had for breakfast that computer hackers would expect a person so labeled to originate games or physics rather than merely being a connoisseur of such things.

One thing that makes this distinction interesting is that it’s a recently-evolved one. When I first edited the Jargon File in 1990, “geek” was just beginning a long march towards respectability. It’s from a Germanic root meaning “fool” or “idiot” and for a long time was associated with the sort of carnival freak-show performer who bit the heads off chickens. Over the next ten years it became steadily more widely and positively self-applied by people with “non-mainstream” interests, especially those centered around computers or gaming or science fiction. From the self-application of “geek” by those people it spread to elsewhere in science and engineering, and now even more widely; my wife the attorney and costume historian now uses the terms “law geek” and “costume geek” and is understood by her peers, but it would have been quite unlikely and a faux pas for her to have done that before the last few years.

Because I remembered the pre-1990 history, I resisted calling myself a “geek” for a long time, but I stopped around 2005-2006 – after most other techies, but before it became a term my wife’s non-techie peers used politely. The sting has been drawn from the word. And it’s useful when I want to emphasize what I have in common with have in common with other geeks, rather than pointing at the more restricted category of “hacker”. All hackers are, almost by definition, geeks – but the reverse is not true.

The word “hacker”, of course, has long been something of a cultural football. Part of the rise of “geek” in the 1990s was probably due to hackers deciding they couldn’t fight journalistic corruption of the term to refer to computer criminals – crackers. But the tremendous growth and increase in prestige of the hacker culture since 1997, consequent on the success of the open-source movement, has given the hackers a stronger position from which to assert and reclaim that label from abuse than they had before. I track this from the reactions I get when I explain it to journalists – rather more positive, and much more willing to accept a hacker-lexicographer’s authority to pronounce on the matter, than in the early to mid-1990s when I was first doing that gig.

Eric S. Raymond, “Geeks, hackers, nerds, and crackers: on language boundaries”, Armed and Dangerous, 2011-01-09.

September 27, 2023

QotD: Geeks and hackers

September 13, 2023

Why Do People In Old Movies Talk Weird?

BrainStuff – HowStuffWorks

Published 25 Nov 2014It’s not quite British, and it’s not quite American – so what gives? Why do all those actors of yesteryear have such a distinct and strange accent?

If you’ve ever heard old movies or newsreels from the thirties or forties, then you’ve probably heard that weird old-timey voice.

It sounds a little like a blend between American English and a form of British English. So what is this cadence, exactly?

This type of pronunciation is called the Transatlantic, or Mid-Atlantic, accent. And it isn’t like most other accents – instead of naturally evolving, the Transatlantic accent was acquired. This means that people in the United States were taught to speak in this voice. Historically Transatlantic speech was the hallmark of aristocratic America and theatre. In upper-class boarding schools across New England, students learned the Transatlantic accent as an international norm for communication, similar to the way posh British society used Received Pronunciation – essentially, the way the Queen and aristocrats are taught to speak.

It has several quasi-British elements, such a lack of rhoticity. This means that Mid-Atlantic speakers dropped their “r’s” at the end of words like “winner” or “clear”. They’ll also use softer, British vowels – “dahnce” instead of “dance”, for instance. Another thing that stands out is the emphasis on clipped, sharp t’s. In American English we often pronounce the “t” in words like “writer” and “water” as d’s. Transatlantic speakers will hit that T like it stole something. “Writer”. “Water”.

But, again, this speech pattern isn’t completely British, nor completely American. Instead, it’s a form of English that’s hard to place … and that’s part of why Hollywood loved it.

There’s also a theory that technological constraints helped Mid-Atlantic’s popularity. According to Professor Jay O’Berski, this nasally, clipped pronunciation is a vestige from the early days of radio. Receivers had very little bass technology at the time, and it was very difficult – if not impossible – to hear bass tones on your home device. Now we live in an age where bass technology booms from the trunks of cars across America.

So what happened to this accent? Linguist William Labov notes that Mid-Atlantic speech fell out of favor after World War II, as fewer teachers continued teaching the pronunciation to their students. That’s one of the reasons this speech sounds so “old-timey” to us today: when people learn it, they’re usually learning it for acting purposes, rather than for everyday use. However, we can still hear the effects of Mid-Atlantic speech in recordings of everyone from Katherine Hepburn to Franklin D. Roosevelt and, of course, countless films, newsreels and radio shows from the 30s and 40s.

(more…)

September 1, 2023

How the term “the Deep State” morphed from left-wing to (extreme, scary, ultra-MAGA) right-wing jargon

Matt Taibbi wants to track the changes in political language in US usage, starting today with “Deep State”:

In July of last year David Rothkopf wrote a piece for the Daily Beast called, “You’re going to miss the Deep State when it’s gone: Trump’s terrifying plan to purge tens of thousands of career government workers and replace them with loyal stooges must be stopped in its tracks.” In the obligatory MSNBC segment hyping the article, poor Willie Geist, fast becoming the Zelig of cable’s historical lowlight reel, read off the money passage:

During his presidency, [Donald] Trump was regularly frustrated that government employees — appointees, as well as career officials in the civil service, the military, the intelligence community, and the foreign service — were an impediment to the autocratic impulses about which he often openly fantasized.

This passage portraying harmless “government employees” as the last patriotic impediment to Trumpian autocracy represented the complete turnaround of a term that less than ten years before meant, to the Beast‘s own target audience, the polar opposite. This of course needed to be lied about as well, and the Beast columnist stuck this landing, too, when Geist led Rothkopf through the eye-rolling proposition that there was “something fishy, or dark, or something going on behind the scenes” with the “deep state”.

Rothkopf replied that “career government officials” got a bad rap because “about ten years ago, Alex Jones and the InfoWars crowd started zeroing in on the deep state, as yet another of the conspiracy theories …”

The real provenance of deep state has in ten short years been fully excised from mainstream conversation, in the best and most thorough whitewash job since the Soviets wiped the photo record clean of Yezhov and Trotsky. It’s an awesome achievement.

Through the turn of the 21st century virtually no American political writers used deep state. In the mid-2000s, as laws like the PATRIOT Act passed and the Bush/Cheney government funded huge new agencies like the Department of Homeland Security, the word was suddenly everywhere, inevitably deployed as left-of-center critique of the Bush-Cheney legacy.

How different was the world ten years ago? The New York Times featured a breezy Sunday opinion piece asking the late NSA whistleblower Thomas Drake — a man described as an inspiration for Edward Snowden who today would almost certainly be denounced as a traitor — what he was reading then. Drake answered he was reading Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry by Marc Ambinder, whose revelations about possible spying on “eighteen locations in the Washington D.C. area, including near the White House, Congress, and several foreign embassies”, inspired the ACLU to urge congress to begin encrypting communications.

On the eve of a series of brutal revelations about intelligence abuses, including the Snowden mess, left-leaning American commentators all over embraced “deep state” as a term perfectly descriptive of the threat they perceived from the hyper-concentrated, unelected power observed with horror in the Bush years. None other than liberal icon Bill Moyers convinced Mike Lofgren — a onetime Republican operative who flipped on his formers and became heavily critical of the GOP during this period — to compose a report called “The Deep State Hiding in Plain Sight“.

August 20, 2023

How to decode book blurbs

In The Critic, “The Secret Author” provides a glossary for industry outsiders to understand what the apparently glowing words of a blurb on a book cover actually mean:

Like many other professions, the book trade is keen on jargon: lots of it, the more the merrier. As with those other professions, it tends to be of two kinds: outward-facing, when publishers communicate with their customers; and inward-facing, when they communicate with other publishers or the people who write the products they sell.

Its function — the function of all professional jargon, it might be said — is simultaneously to create an easily intelligible code for the benefit of insiders and (frankly) to mystify and impress those beyond the loop.

Publishers’ outward-facing jargon can be conveniently observed in the blurbs printed on book jackets. These are full of code words which, you may be surprised to learn, usually have very little to do with the contents.

A good place to start in any consideration of jacket copy might be the late Anthony Blond’s still invaluable The Publishing Game (1971), in which the one-time kingpin of Anthony Blond Ltd and various successor firms identifies the real meaning of several of the key publishers’ cliches of the late 1960s.

They include Kafkaesque (“obscure”), Saga (“the editor suggested cuts but the author was adamant”), Frank or outspoken (“obscene”) and Well-known, meaning “unknown”. To these may be added Rebellious (“the author uses bad language”), Savage (“the author revels in sadism”), Ingenious (“usually means unbelievable”) and Sensitive (“homosexual”). Blond also offers a list of OK writers (Kafka, J.D. Salinger) with whom promising newcomers may profitably be compared.

Naturally, Blond’s list is of its time: nobody these days would think of labelling a gay coming-of-age novel “sensitive”. On the other hand, if the content has been superannuated, here in 2023 very little has changed in the form — which is to say that the modern book blurb is still awash with genteel euphemism and downright obfuscation.

Sometimes a blurb-adjective means its exact opposite. Thus powerful can invariably be construed as “weak”, whilst audacious or bold generally means “deeply conventional”. Shocking, obviously, means “not shocking” and challenging “not at all challenging”.

Then there are the contemporary buzzwords: transgressive, used to describe anything even a degree or two north of the sexual or ideological status quo; or immersive, which is another way of saying “reasonably engrossing”.

July 30, 2023

QotD: Thomas Hobbes and Leviathan

… I’m not trying to cast Thomas Hobbes, of all people, as some kind of proto-Libertarian. The point is, for Hobbes, physical security was the overriding, indeed obsessive, concern. Indeed, Hobbes went so far as to make his peace with Oliver Cromwell, for two reasons: First, his own physical safety was threatened in his Parisian exile (a religious thing, irrelevant). Second, and most importantly, Cromwell was the Leviathan. The Civil Wars didn’t turn out quite like Hobbes thought they would, but regardless, Cromwell’s was the actually existing government. It really did have the power, and when you boil it down, whether the actually existing ruler is a Prince or a Leviathan or something else, might makes right.

One last point before we close: As we’ve noted here probably ad nauseam, modern English is far less Latinate than the idiom of Hobbes’s day. Hobbes translated Leviathan into Latin himself, and while I’m not going to cite it (not least because I myself don’t read Latin), it’s crucial to note that, for the speakers of Hobbes’s brand of English, “right” is a direction – the opposite of left.

I’m oversimplifying for clarity, because it’s crucial that we get this – when the Barons at Runnymede, Thomas Hobbes, hell, even Thomas Jefferson talked about “rights”, they might’ve used the English word, but they were thinking in Latin. They meant ius – as in, ius gentium (the right of peoples, “international law”), ius civile (“civil law”, originally the laws of the City of Rome itself), etc. Thus, if Hobbes had said “might makes right” – which he actually did say, or damn close, Leviathan, passim – he would’ve meant something like “might makes ius“. Might legitimates, in other words – the actually existing power is legitimate, because it exists.

We Postmoderns, who speak only English, get confused by the many contradictory senses of “right”. The phrase “might makes right” horrifies us (at least, when a Republican is president) because we take it to mean “might makes correct” – that any action of the government at all is legally, ethically, morally ok, simply because the government did it. Even Machiavelli, who truly did believe that might makes ius, would laugh at this – or, I should say, especially Machiavelli, as he explicitly urges his Prince, who by definition has ius, to horribly immoral, unethical, “illegal” (in the “law of nations” sense) behavior.

So let’s clarify: Might legitimates. That doesn’t roll off the tongue like the other phrase, but it avoids a lot of confusion.

Severian, “Hobbes (II)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-11.

July 19, 2023

Ever wonder where the term “two-spirit” came from?

In Spiked, Malcolm Clark explains the origin of the now commonly used term as a portmanteau for many different words — with significant variation in meaning — in indiginous languages:

The term two-spirit was first formally endorsed at a conference of Native American gay activists in 1990 in Winnipeg in Canada. It is a catch-all term to cover over 150 different words used by the various Indian tribes to describe what we think of today as gay, trans or various forms of gender-bending, such as cross-dressing. Two-spirit people, the conference declared, combine the masculine and the feminine spirits in one.

From the start, the whole exercise reeked of mystical hooey. Myra Laramee, the woman who proposed the term in 1990, said it had been given to her by ancestor spirits who appeared to her in a dream. The spirits, she said, had both male and female faces.

Incredibly, three decades on, there are now celebrities and politicians who endorse the concept or even identify as two-spirit. The term has found its way into one of Joe Biden’s presidential proclamations and is a constant feature of Canadian premier Justin Trudeau’s doe-eyed bleating about “2SLGBTQQIA+ rights”.

The term’s success is no doubt due in part to white guilt. There is a tendency to associate anything Native American with a lost wisdom that is beyond whitey’s comprehension. Ever since Marlon Brando sent “Apache” activist Sacheen Littlefeather to collect his Oscar in 1973, nothing has signalled ethical superiority as much as someone wearing a feather headdress.

The problem is that too many will believe almost any old guff they are told about Native Americans. This is an open invitation to fakery. Ms Littlefeather, for example, may have built a career as a symbol of Native American womanhood. But after her death last year, she was exposed as a member of one of the fastest growing tribes in North America: the Pretendians. Her real name was Marie Louise Cruz. She was born to a white mother and a Mexican father, and her supposed Indian heritage had just been made up.

Much of the fashionable two-spirit shtick is just as fake. For one thing, it’s presented as an acknowledgment of the respect Indian tribes allegedly showed individuals who were gender non-conforming. Yet many of the words that two-spirit effectively replaces are derogatory terms.

In truth, there was a startling range of attitudes to the “two-spirited” among the more than 500 separate indigenous Native American tribes. Certain tribes may have been relaxed about, say, effeminate men. Others were not. In his history of homosexuality, The Construction of Homosexuality (1998), David Greenberg points out that those who are now being called “two spirit” were ridiculed by the Papago, held in contempt by the Choctaws, disliked by the Cocopa, treated by the Seven Nations with “the most sovereign contempt” and “derided” by the Sioux. In the case of the Yuma, who lived in what is now Colorado, the two-spirited were sometimes treated as rape objects for the young men of the tribe.

June 25, 2023

British schoolchildren mock their oh-so-woke teachers

In Christopher Gage’s weekly round-up, I discovered that I shared a trait with Ted Kaczynski (“austere anarchist scholar” as US mainstream media might have described him). Not just any trait, but the one that ended up putting him in prison after nearly twenty years of sending bombs through the mail:

… Ted insisted on the proper use of the idiom, “You can’t eat your cake and have it, too”. Ted rejected the common and logically fraught version: “You can’t have your cake and eat it, too”. Indeed, you can. You must have your cake if you are to eat your cake. You cannot have your cake once you’ve eaten your cake.

That turn of phrase helped F.B.I agents snare Ted. His sister-in-law read his essay, recognised the writing style, and the peculiar diction, and then grassed him up to the rozzers.

For the record, this may be the only point of agreement I have with that noted austere scholar, although I’ve never read any of his writings to find out.

Another amusing incident involved children taking the Mickey out of ultra-progressive teachers in British schools:

Last week, schoolchildren in Sussex dropped themselves into the soup after suggesting that their fellow classmate is not actually a cat.

Two thirteen-year-old girls at Rye College were told they “should go to a different school” if they didn’t believe that a girl could identify as a cat.

During a “life education” class, the pair said there was “no such thing as agender” and: “If you have a vagina, you’re a girl, and if you have a penis, you’re a boy — that’s it.”

When they queried how someone could identify as a cat, the pair were blasted for questioning their classmate’s identity.

An investigation found children at schools across the land now identify as dinosaurs and horses. Another often dons a cape and demands to be acknowledged as a moon. Another identifies as Bambi.

After the hysteria simmered, it became obvious what was going on here. And it too became obvious that this is a good thing.

Reader, these children are taking the Mickey.

When confronted with obvious nonsense held by their preachy, supposedly superior teachers, these kids cannot resist mocking them to a nub.

After all, if one can identify as whatever one wants then that includes anything one wants. For teenagers primed with mischief, this is just too good a brew not to sup on a daily basis.

And it is a promising sign. Ridicule, the sharp-elbowed sister of truth, is essential to all progress. Clearly, these kids are unafraid to think for themselves and are determined to see that which is beyond their own nose.

Perhaps this is the beginning of the end of what almost everybody knows to be patent nonsense. As history assures us, once something becomes a laughingstock it soon dies of ridicule.

As James Thurber put it, that which cannot withstand laughter is not a good thing.

June 15, 2023

Sarah Hoyt objects to being an “imaginary creature”

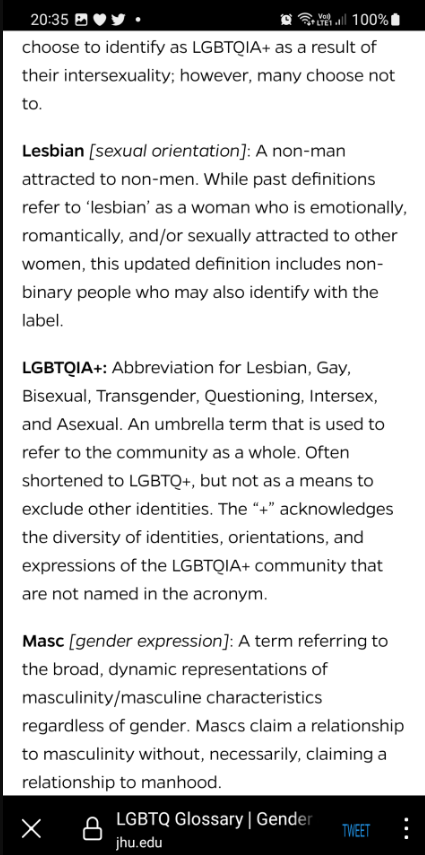

Recent revisions to the quasi-official dictionary of the woke English language seem to have classified individuals like Sarah as “non-men”:

I was born female in a country that was profoundly patriarchal and, back then, patriarchal without guilt. So, it was acceptable to make jokes about women being dumber than men. And it was acceptable for teachers to assume you were dumb because female.

Most of these things amused me. It was always fun in mixed classes after the first test to watch the teacher look at my test and at the boys in the class trying to figure out what parent was so cruel as to name their son a girl’s name.

I enjoyed breaking people’s minds. And once I was known in a group or place, I was not treated as inferior. The only things that truly annoyed me were the ones I thought were arbitrary restrictions, like not going out after 8 pm alone. Took flaunting them a few times to find out they weren’t arbitrary. Or rather, they were arbitrary but since culture-wide flaunting was dangerous, and I was lucky not to pay for the flaunting with life or limb.

Yes, I went through a phase of screaming that I was just as good as any man. Then realized it was true and stopped screaming it.

Then got married and had kids, and realized I was just as good but different. I could do things men couldn’t do. Parenthood is different as a woman. And none of it mattered to my worth, just like being short and having brown hair doesn’t make me inferior to tall blonds. Just different.

And even though I’m a highly atypical woman, at the beginning of my sixth decade, I find myself completely at peace with the fact I am a woman and not apologetic at all for it.

Imagine my surprise when I found out women don’t exist. There’s only man and non-man.

This nonsense, from here, has got to stop. When you get so “inclusive” you’re excluding an entire biological sex (but curiously not the other) you might want to re-evaluate your principles. Also, your sanity.

Yes, I know, saying this makes me a TERF, which is nonsense. Maybe a TERNF, since I’ve not called myself a feminist since I was 18 and realized feminism aimed for making women “win” at men’s expense. It wasn’t aiming for equality but for “equity” and since I never needed a movement to outcompete males, I decided it was spinach and to h*ll with it.

Also I’m not trans-exclusionary. If women don’t exist, what the heck are men who are trans trans TO? Non-man? Uh … what? What are drag queens imitating? Is it just non-man?

June 14, 2023

“‘Misogyny’ is overtaking ‘fascist’ in the ‘I Don’t Own a Dictionary’ championships”

Christopher Gage suspects that George Orwell lived in vain:

In his essay, “Politics and the English Language”, George Orwell lamented the decline in the standards of his mother tongue.

For Orwell, all around him lay the evidence of decay. Orwell argued sloppy language came from and led to sloppy thinking:

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language […] It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

With his effortless knack for saying in plain English the resonant and enduring, Orwell’s dictum is obvious as soon as uttered.

Orwell wrote that back in 1946. What would the author of Animal Farm and 1984 make of today’s standards?

“Misogyny” is overtaking “fascist” in the “I Don’t Own a Dictionary” championships.

Spend five minutes online, and you’ll encounter words defined in their starkest definitions. Words like “misogyny”, “misandry”, and “narcissist”, once possessed specific meanings. Now they mean whatever the speaker claims they mean.

The beauty of the English language lies in its precision. Sadly, those who populate the land which spawned the English language wield the language with all the grace and precision of a meat hook.

According to The Guardian, the recent Finnish election was suppurated with misogyny and fascism.

In that election, the one debased in misogyny and fascism, the losing incumbent Sanna Marin, a woman, won more seats in parliament than in 2019. The three candidates with the most votes — Riikka Purra, Sanna Marin and Elina Valtonen — were all women. Women lead seven of the nine parties returned to parliament — including the “far-right” Finns Party.

The Guardian didn’t permit reality to spoil a good headline.

As Orwell had it, “Fascism” is a hollow word. In the essay mentioned above, he said: “The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’.” In modern parlance, the same applies to “misogyny”. “misandry”, “narcissism”, “gaslighting”, and just about every other buzzword shoehorned into a HuffPost headline.

June 10, 2023

QotD: The word “objectively”

For years past I have been an industrious collector of pamphlets, and a fairly steady reader of political literature of all kinds. […] When I look through my collection of pamphlets — Conservative, Communist, Catholic, Trotskyist, Pacifist, Anarchist or what-have-you — it seems to me that almost all of them have the same mental atmosphere, though the points of emphasis vary. Nobody is searching for the truth, everybody is putting forward a “case” with complete disregard for fairness or accuracy, and the most plainly obvious facts can be ignored by those who don’t want to see them. The same propaganda tricks are to be found almost everywhere. It would take many pages of this paper merely to classify them, but here I draw attention to one very widespread controversial habit — disregard of an opponent’s motives. The key-word here is “objectively”.

We are told that it is only people’s objective actions that matter, and their subjective feelings are of no importance. Thus pacifists, by obstructing the war effort, are “objectively” aiding the Nazis; and therefore the fact that they may be personally hostile to Fascism is irrelevant. I have been guilty of saying this myself more than once. The same argument is applied to Trotskyism. Trotskyists are often credited, at any rate by Communists, with being active and conscious agents of Hitler; but when you point out the many and obvious reasons why this is unlikely to be true, the “objectively” line of talk is brought forward again. To criticize the Soviet Union helps Hitler: therefore “Trotskyism is Fascism”. And when this has been established, the accusation of conscious treachery is usually repeated.

This is not only dishonest; it also carries a severe penalty with it. If you disregard people’s motives, it becomes much harder to foresee their actions. For there are occasions when even the most misguided person can see the results of what he is doing. Here is a crude but quite possible illustration. A pacifist is working in some job which gives him access to important military information, and is approached by a German secret agent. In those circumstances his subjective feelings do make a difference. If he is subjectively pro-Nazi he will sell his country, and if he isn’t, he won’t. And situations essentially similar though less dramatic are constantly arising.

In my opinion a few pacifists are inwardly pro-Nazi, and extremist left-wing parties will inevitably contain Fascist spies. The important thing is to discover which individuals are honest and which are not, and the usual blanket accusation merely makes this more difficult. The atmosphere of hatred in which controversy is conducted blinds people to considerations of this kind. To admit that an opponent might be both honest and intelligent is felt to be intolerable. It is more immediately satisfying to shout that he is a fool or a scoundrel, or both, than to find out what he is really like. It is this habit of mind, among other things, that has made political prediction in our time so remarkably unsuccessful.

George Orwell, “As I Please”, Tribune, 1944-12-08.

May 21, 2023

QotD: Swearing

In 1927, Robert Graves published a little book called Lars Porsena or the Future of Swearing and Improper Language. He noted a recent decline in the use of foul language by the English, and predicted that this decline would continue indefinitely, until foul language had all but disappeared from the average man’s vocabulary. History has not borne him out, to say the least: indeed, I have known economists make more accurate predictions.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Get stuffed, sunshine”, The Independent, 1998-10-10.

May 9, 2023

Apparently, we are all misunderstanding the Trudeau masterplan

All the smoke about Canada not having a national identity is there to hide Justin Trudeau continuing his father’s masterplan to DESTROY QUEBEC:

“Quebec caught in a trap. French forced into decline. Its political influence doomed. 12 million residents in Montreal. Quebec with 5 million. Ottawa’s grand plan explained. Justin is smarter than we think. They want to assimilate us all. All this, without any debate. Two catastrophic scenarios.”

Forget King Charles III’s coronation or the Liberal Party Convention. If you woke up Saturday morning in Quebec, this was the apocalyptic front page that graced your browser, courtesy of the Journal de Montreal:

The Journal‘s cri-de-coeur was in response to the federal government’s increase in the annual immigration level to 500,000 people. This increase, designed to boost the population of Canada to 100 million by the end of the century, would marginalize Quebec’s influence within Canada. It is estimated that Quebec’s overall share of the Canadian population would fall from 25 to 10%, while francophone Quebecers would be in the minority within their own province for the first time in 500 years.

This would displace Quebec from the center of power in Canada. Its official language, French, would be relegated to the same status as all languages and cultures other than English. Instead of being one of Canada’s two official languages, French would merely be one of many, and Quebec, no longer a nation, but a province like any other.

But wait: Journal authors further suggest that this was the grand plan of Prime Ministers Justin and Pierre Elliott Trudeau all along. In a very colorful column, “How the Trudeaus Drowned Quebec“, columnist Richard Martineau even compares the current PM to the protagonist of an infamous Stephen King novel:

“For Justin, Canada is not a country.

It is a hotel, an Airbnb.

And Quebec is just one of the many rooms in this vast real estate complex.

Room 237, here. Like the one in the movie The Shining.

Come, drop your bags and settle in! All we ask is that you pay your taxes.It’s true that Trudeau Sr. paved the way for the reduction of Quebec’s power in Canada, but it didn’t start with his 1981 Charter of Rights, as the Journal claims. It actually began a decade earlier, in 1971, with the creation of Canada’s Official Multiculturalism Policy. The policy enshrined the idea that linguistic and cultural minorities in Canada should be encouraged to preserve their heritage, and allocated federal funding to help them do so.

Official multiculturalism was both a vote-getter for the Liberals and a means of diffusing the English-French “two solitudes” paradigm that was threatening to tear the country apart. At the time, Canada had just lived through the October Crisis of 1970, which had seen Trudeau invoke the War Measures Act in response to terrorist acts by the Front de Liberation du Quebec. Official multiculturalism was seen as a way to boost the federalist cause by aligning the interest of linguistic and cultural minorities within Quebec with those of the federal government.

The larger impact, however, was to enshrine multiculturalism outside Quebec, where most minorities settled, and where garnering favour with different cultural communities became standard operating procedure, particularly for the federal Liberal party. Immigration thus became a politically untouchable issue, except in Quebec, where the protection of the French language continued to take precedence over concerns for minority rights.

May 6, 2023

QotD: The luxury beliefs of the leisure class

Thorstein Veblen’s famous “leisure class” has evolved into the “luxury belief class”. Veblen, an economist and sociologist, made his observations about social class in the late nineteenth century. He compiled his observations in his classic work, The Theory of the Leisure Class. A key idea is that because we can’t be certain of the financial standing of other people, a good way to size up their means is to see whether they can afford to waste money on goods and leisure. This explains why status symbols are so often difficult to obtain and costly to purchase. These include goods such as delicate and restrictive clothing, like tuxedos and evening gowns, or expensive and time-consuming hobbies like golf or beagling. Such goods and leisurely activities could only be purchased or performed by those who did not live the life of a manual laborer and could spend time learning something with no practical utility. Veblen even goes so far as to say, “The chief use of servants is the evidence they afford of the master’s ability to pay.” For Veblen, butlers are status symbols, too.

[…]

Veblen proposed that the wealthy flaunt status symbols not because they are useful, but because they are so pricey or wasteful that only the wealthy can afford them. A couple of winters ago it was common to see students at Yale and Harvard wearing Canada Goose jackets. Is it necessary to spend $900 to stay warm in New England? No. But kids weren’t spending their parents’ money just for the warmth. They were spending the equivalent of the typical American’s weekly income ($865) for the logo. Likewise, are students spending $250,000 at prestigious universities for the education? Maybe. But they are also spending it for the logo.

This is not to say that elite colleges don’t educate their students, or that Canada Goose jackets don’t keep their wearers warm. But top universities are also crucial for inculcation into the luxury belief class. Take vocabulary. Your typical working-class American could not tell you what “heteronormative” or “cisgender” means. But if you visit Harvard, you’ll find plenty of rich 19-year-olds who will eagerly explain them to you. When someone uses the phrase “cultural appropriation”, what they are really saying is “I was educated at a top college”. Consider the Veblen quote, “Refined tastes, manners, habits of life are a useful evidence of gentility, because good breeding requires time, application and expense, and can therefore not be compassed by those whose time and energy are taken up with work.” Only the affluent can afford to learn strange vocabulary because ordinary people have real problems to worry about.

The chief purpose of luxury beliefs is to indicate evidence of the believer’s social class and education. Only academics educated at elite institutions could have conjured up a coherent and reasonable-sounding argument for why parents should not be allowed to raise their kids, and that we should hold baby lotteries instead. Then there are, of course, certain beliefs. When an affluent person advocates for drug legalization, or defunding the police, or open borders, or loose sexual norms, or white privilege, they are engaging in a status display. They are trying to tell you, “I am a member of the upper class”.

Affluent people promote open borders or the decriminalization of drugs because it advances their social standing, and because they know that the adoption of those policies will cost them less than others. The logic is akin to conspicuous consumption. If you have $50 and I have $5, you can burn $10 and I can’t. In this example, you, as a member of the upper class, have wealth, social connections, and other advantageous attributes, and I don’t. So you are in a better position to afford open borders or drug experimentation than me.

Or take polyamory. I recently had a revealing conversation with a student at an elite university. He said that when he sets his Tinder radius to 5 miles, about half of the women, mostly other students, said they were “polyamorous” in their bios. Then, when he extended the radius to 15 miles to include the rest of the city and its outskirts, about half of the women were single mothers. The costs created by the luxury beliefs of the former are bore by the latter. Polyamory is the latest expression of sexual freedom championed by the affluent. They are in a better position to manage the complications of novel relationship arrangements. And even if it fails, they have more financial capability, social capital, and time to recover if they fail. The less fortunate suffer the damage of the beliefs of the upper class.

Rob Henderson, “Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class – An Update”, Rob Henderson’s Newsletter, 2023-01-29.

April 22, 2023

Epistemology, but not using the term “epistemology” because reasons

At Founding Questions, Severian responds to a question about the teaching profession in our ever-more-self-beclowning world:

Proposed coat of arms for Founding Questions by “urbando”.

The Latin motto translates to “We are so irrevocably fucked”.

I know a guy who teaches at a SPLAC where they have some “common core” curriculum — everyone in the incoming class, regardless of major, is required to take a few set courses, and all of them revolve around that question. How do we know what we know? So it’s not just a public school / grade school thing. And epistemology IS fascinating … almost as fascinating as the fact that the word “epistemology” never shows up on my buddy’s syllabi.

I think the problem is especially acute for “teachers”, because the Dogmas of the Church of Woke are so ludicrous that it takes real effort to not see the obvious absurdities. It takes real hermeneutical talent to reconcile the most obvious empirical facts with the Dogmas of the Faith, and very few kids have it. So they either completely check out, or just repeat the Dogmas by rote.

The other problem has to do with teacher training. I know a little bit about this (or, at least, a little bit about how it stood 15 years ago), because a) I was “dating” an Education Theory person, and b) I went through Flyover State’s online

indoctrinationeducation Certificate Program.The former is just awful, even by ivory tower standards, so I’ll spare you the gory details. Just know that however bad you think “social science” is, it’s way way worse. The “certification program” was something I got my Department to sign off on — I was the guy who “knew computers” (which is just hilarious if you know me in real life; I’m all but tech-illiterate), so I got assigned all the online classes, which the Department fought against with all its might, and only grudgingly agreed to offer when the Big Cheese threatened to pull some $$$ if they didn’t. So even though I wouldn’t have been eligible for all the benefits and privileges thereunto appertaining, me being a lowly adjunct, none of the real eggheads could bring themselves to do it, so I was the guy.

The Education Department, being marginally smarter than the History Department, saw which way the wind was blowing, so they started offering big money incentives for professors to sign up for this “online teaching certification program” they’d dreamed up. No, really: It was something like $5000 for a two course, which really meant “two hours a day, four days a week,” because academia works like that (it’s a 24/7 job, remember — 24 hours a week, 7 months a year). By my math, $5000 by 16 hours is something like $300 an hour, so hell yeah I signed right up …

It was torture. Sheer torture. I knew it would be, but goddamn, man. Take the worst corporate struggle session you’ve ever been forced to attend, put it on steroids. Make the “facilitator” — not professor, by God, not in Education! — the kind of sadistic bastard that got kicked out of Viet Cong prison guard school for going overboard. Add to that the particularities of the Education Department, where all of academia’s worst pathologies are magnified. You know how egghead prose hews to the rule “Why use 5 words when 50 will do?” In the Ed Department, it’s “why use 50 when 500 will do.” The first two hours of the first two struggle sessions were devoted to Bloom’s Taxonomy of Success Words, and click that link if you dare.

I know y’all won’t believe this, but I’ll tell you anyway: I spent more than an hour rewriting the “objectives” section of my class syllabus to conform to that nonsense. Instead of just “Students will learn about the origins, events, and outcomes of the US Civil War,” I had to say shit like “Engaging with the primary sources” and “evaluating historical arguments,” and yes, the “taxonomy” buzzwords had to be both underlined and italicized, for reasons I no longer remember, but which were of course retarded.

Given that this is fairly typical Ed Major coursework, is it any surprise that they have no idea what learning is?

April 13, 2023

QotD: The real purpose of modern-day official commissions

After the riots were over, the government appointed a commission to enquire into their causes. The members of this commission were appointed by all three major political parties, and it required no great powers of prediction to know what they would find: lack of opportunity, dissatisfaction with the police, bla-bla-bla.

Official enquiries these days do not impress me, certainly not by comparison with those of our Victorian forefathers. No one who reads the Blue Books of Victorian Britain, for example, can fail to be impressed by the sheer intellectual honesty of them, their complete absence of any attempt to disguise an often appalling reality by means of euphemistic language, and their diligence in collecting the most disturbing information. (Marx himself paid tribute to the compilers of these reports.)

I was once asked to join an enquiry myself. It was into an unusual spate of disasters in a hospital. It was clear to me that, although they had all been caused differently, there was an underlying unity to them: they were all caused by the laziness or stupidity of the staff, or both. By the time the report was written, however (and not by me), my findings were so wrapped in opaque verbiage that they were quite invisible. You could have read the report without realising that the staff of the hospital had been lazy and stupid; in fact, the report would have left you none the wiser as to what had actually happened, and therefore what to do to ensure that it never happened again. The purpose of the report was not, as I had naively supposed, to find the truth and express it clearly, but to deflect curiosity and incisive criticism in which it might have resulted if translated into plain language.

Theodore Dalrymple, “It’s a riot”, New English Review, 2012-04.