Security empires come and go. While they serve a purpose, their citizens are willing to pay the cost. When they become too expensive to maintain, they simply fold, or get ground under. They work to purpose, or stop.

Conquest empires rarely outlive their founders, or only last a few generations. Alexander’s generals, or Charlemagne’s children and grandchildren, dividing and subdividing into smaller and smaller units, is the norm for such empires. (If not straight collapse when the dictator holding it all together vanishes.)

The only “conquest” empires that have held up are those that send settlers into the lands of hunter-gatherers or nomads. The United States, Russia and Australia being good examples. (But the only reason they can hold up is if the captured territory can be converted into a functional part of the state and society … something the US and Australia have largely managed … Russia’s attempts to enforce this unity by repression of its more developed conquered peoples have not been so successful over the last few centuries, and it is unlikely that China will do much better long-term no matter how much repression it introduces into its recent conquests of established societies like Tibet and the Uyghurs.)

Which leaves only trade empires as potentially successful long term options. And only because their success is not measured by sustaining the political unity of the “empire”, but by sustaining its economic goals.

The most successful empire in world history is the British empire, which could delightedly declare itself obsolete in the 1920s, and again (after having to work mostly co-operatively to fight World War Two) in the 1950s. Both times it encouraged the member states to go look after themselves (some successfully and some less so), and yet it still managed to leave an almost completely secure legacy for its existence … relatively safe international free trade routes. (The almost complete elimination of both piracy and slavery worldwide just being minor side benefits of the British Empire.)

For an empire developed “in a fit of absent mindedness”, and as a byproduct of trying to develop free trade around the world: the measure of success has to be the Commonwealth of Nations – comprising 54 nations with about 1/3 of the world’s population, getting together to play cricket every year and hold a Commonwealth Games every 4 years.

This is not an empire that copllapsed, or was destroyed. This is an empire that over a century or so (from granting independent Dominion status to Canada in 1886 [Canadians stoutly maintain it was 1867], Australia 1901, New Zealand and South Africa pre-Great War, Ireland and Egypt interwar, India and Pakistan post war, large parts of Asia and Africa in the 60s and 70s etc.); nonetheless developed and secured the international free trade system that the world has embraced. (Including a re-integration by an early exit-er from the empire … the 13 out of 35 British north American colonies that became the United States … and who finally inherited the title of world policeman when the rest of the Commonwealth nations had got sick of the whole thing.)

Nigel Davies, “Types of Empires: Security, Conquest, and Trade”, rethinking history, 2020-05-02.

August 8, 2020

QotD: The British Empire

July 20, 2020

QotD: Protectionists misunderstand the role of money

A Protectionist is Someone Who … thinks that the ultimate purpose of producing goods and services is to use them to acquire as much money as possible. Unlike a free-trader who understands that the purpose of producing goods and services is to acquire for yourself and your family as many as possible real goods and services to raise as much as possible your standard of living – and who understands that exchanging for money what you directly produce is merely a means of lowering your cost of acquiring in exchange as many as possible goods and services produced by others – the protectionist thinks that the ultimate purpose of producing real goods and services is to use them to acquire as much money as possible.

The Econ 101 teacher typically draws on the white board a diagram of two countries trading with each other. Country A is shown exporting (say) steel to country B in exchange for dollars, and then using those dollars to buy lumber from country B. The Econ 101 teacher informs his or her class that, while these exchanges are mediated by dollars, what ultimately is going on in this diagram is that the people of country A produce steel and send some of that steel to the people of country B because the people of country A want lumber from country B. Likewise, the people of country B produce lumber and send some of it to the people of country A because the people of country B want steel from country A. “The money that you see, class,” explains the Econ 101 teacher, “merely facilitates the exchange of steel for lumber. What’s important here is the getting of steel and of lumber. Money is a tool used by the people of country A to transform some of the steel they produce into lumber that they want to consume. Likewise, money is a tool used by the people of country B to transform some of the lumber they produce into steel that they want to consume.”

The protectionist thinks of this hypothetical two-country exchange entirely differently from the way that the Econ 101 teacher thinks of it. For the protectionist, the people of country A produce steel as a means of getting money; that is the ultimate goal. And the people of country B produce lumber as a means of getting money; that – the getting of money – is the ultimate goal. While for the Econ 101 teacher the two-country diagram that he or she draws is meant to show how money facilitates the ultimate acquisition by the peoples of each country of real goods, for the protectionist the diagram seems to show that the production of real goods is a means of facilitating the ultimate acquisition by the peoples of each country of money.

Don Boudreaux, “A Protectionist is Someone Who…”, Café Hayek, 2018-04-10.

May 3, 2020

The Great Exhibition of 1851

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at one of the biggest popular events of Queen Victoria’s reign, the Great Exhibition:

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851, image from the 1852 book Dickinsons’ comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Wikimedia Commons.

On this day, in 1851, Londoners were finally allowed to enter one of the most spectacular edifices to grace their city. Over the previous months they had watched it spring up in Hyde Park — the largest enclosed structure that had ever been built, and made with three hundred thousand of the largest panes of glass ever produced. Set against the blackened, soot-stained buildings of London, the massive glass edifice gleamed. It soon became known as the Crystal Palace.

Although it no longer exists — it was rebuilt in Sydenham, but the new version burnt down in the 1930s — the fame of the Crystal Palace endures. The same goes for the event that it was originally built for, the Great Exhibition of 1851. But, despite that name-recognition, I’ve found that most people don’t really know what the Great Exhibition was for. Yes, it attracted six million visitors in the space of just a few months — an estimated two million people, almost a tenth of the entire population of Great Britain, most of them returning again and again. But why? I must admit, despite having mentioned the event before in some of my work, I’d never really considered it properly before I started researching the history of the Society of Arts.

The idea of such an exhibition in Britain originated with the Society’s secretary in the 1840s, the civil engineer Francis Whishaw. He had seen the use of industrial exhibitions in France, as a means of catching up with Britain in terms of technology. Every few years since 1798, the French government had held an exhibition of its national industries in Paris. The state paid for everything — a grand temporary building, as well as the expenses of the exhibitors — and the head of state himself awarded medals and cash prizes for the bet works on display. Some of the very best exhibitors were even admitted to the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest order of merit. The benefits to exhibitors were so high that essentially every manufacturer wished to take part. In the days before GDP statistics, the exhibitions were thus an effective means of getting a detailed snapshot of the nation’s manufacturing capabilities. An exhibition served as the nation’s industrial audit.

[…]

Although there had been a few local exhibitions of industry in Britain in the late 1830s and early 1840s, there had been nothing on a national scale to rival the French ones. So Francis Whishaw began the work of getting the Society to organise such an event — a national exhibition of industry for Britain. His initial plan came to nothing, partly as he left the Society to take another job, but in the late 1840s the project was resurrected by a new member of the Society, a civil servant named Henry Cole. In fact, Cole almost entirely took over the Society in the late 1840s, turning it into an exhibition-holding organisation. It held exhibitions devoted to particular living artists, on ancient and medieval art, on inventions, and especially on industrial design — what Cole liked to call “art-manufactures”. And, at the 1849 national exhibition in Paris, he adopted an idea that had already been floated for some years by French officials: an international exhibition, to show the industry of all nations.

This was the crucial step. The idea of an international exhibition of industry appealed to the free trade movement in Britain, which had achieved success in the 1840s with the abolition of the Corn Laws. By displaying the products of other nations, the argument went, British consumers would demand that they be able to buy them more cheaply. And free trade would hopefully bring an end to war, too. Free trade campaigners argued that the productive classes of rival nations competed peacefully, simply by trying to outdo one another in the quality and quantity of what they produced. It was the landed aristocracy, they argued, who let the competition become violent, feeding their pride by causing destruction. Thus, a grand exhibition of the products of all nations — the Great Exhibition — would be a physical manifestation of free trade and international harmony: a “competition of arts, and not of arms”.

The Great Exhibition thus had many roles. It was partly born of national paranoia, about French industrial catch-up, as well as about Britain being the first to hold such an event. It was also about exciting competitive emulation between manufacturers, showing consumers what they did not know they wanted, and achieving world peace and free trade. It certainly spurred on dozens of examples of international cooperation. In fact, just the other day I discovered that the first international chess tournament was held in London to coincide with the exhibition. And it served as an audit of the world’s industries, allowing people to judge who was ahead and who was behind. It thereby gave domestic reformers the ammunition to push for changes in areas where Britain seemed to be falling behind, in areas like education, intellectual property, and design. But more on those another time.

March 10, 2020

QotD: Free trade versus protectionism

It is a myth that free trade is unproven in practice. Forget that countries with freer trade have both higher per-capita incomes and faster rates of economic growth. Look instead at the essentials of the case. Each and every day you trade freely with many merchants. Do you think that you and your family would be enriched if your neighbor extracted punitive payments from you whenever you buy some item that your neighbor judges to be from a seller located too distant from your neighborhood? Every day Arizonans trade freely with Texans and Rhode Islanders. Do you think that Arizonans would be enriched if the government of that state obstructed their ability to trade as they choose with people located in other states?

People trade freely countless times, each and every day. Yes, yes, I’m well aware that such trade isn’t ideally free. Occupational-licensing restrictions, for example, unjustly and harmfully obstruct domestic trade. But the fact remains that today within each country – including within the U.S. – trade is not typically obstructed based on geographic location or political boundaries. And therefore people buy and sell freely within countries. If the case for a policy of free trade were not practical – if it were only a theoretical curiosity – then it would be true that ordinary people would be even richer if the state obstructed their abilities to trade with each other domestically.

It’s a myth also that the economic case for a policy of free trade in any one country requires that other governments also practice free trade. The case for a policy of free trade is, at bottom, a case for unilateral free trade: while nearly everyone in the world would be better off if all governments adopted policies of free trade, nearly everyone in the home country would be better off if the home government adopts a policy of free trade regardless of the policies of other governments.

Protectionism is a nasty mash of logical fallacies, half-truths, hubris, economic ignorance, and cronyist apologetics.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2017-12-18.

January 23, 2020

The EU apparently fears a “Singapore on the Thames”

In the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall explains why the EU negotiators are reportedly offering a much worse trade deal to the United Kingdom than they’ve already agreed with Canada, Japan, and other trading partners:

Take, for example, this idea of Singapore on Thames. It’s trivially easy to rally the peeps against one or other relaxation of regulation. Chlorine washed chicken for example. But what about lifting the entire burden? Singapore is, after all, about 50% richer than Britain on a per capita basis. The correct question therefore is would you like a 50% pay raise at the price of shooting all the bureaucrats? Given the manner in which the bureaucrats don’t want the question even asked we have a reasonable enough guide that the answer would be yes.

Which is why the terms on offer to a Britain which could do the SonT thing are so terrible. Because of SonT succeeded it would be a death blow to the entire idea of how Europe is regulated. Lille, Leipzig and Livorno will all put up with interfering bureaucracy because that’s just the way the world is. But if Les Rosbifs become richer by half again simply by that bonfire of the regulations then the auto da fes will light up all over Europe.

So, yes, of course the EU is offering shit trade terms. They can’t allow an independent and free Britain to succeed. That we will anyway is what will bring that freedom and liberty to the continent – once again. For as so often it will be us that saves Europe from itself.

January 9, 2020

Addressing overblown fears of “regulatory divergence” after Brexit

Tim Worstall explains why worries about “regulatory divergence” are not very sensible:

So now we get to – having agreed that Brexit is going to happen – having to decide what the new trade deal is going to be. At which point there are all sorts of people insisting that we shouldn’t have regulatory divergence. Yet gaining that regulatory divergence is the very point of our having Brexit. We want to be able to do things differently than the European Union.

Thus this sort of worry is thinking about it the wrong way around:

Brexit is nearly done, but don’t expect an easy ride on trade. The EU is terrified of regulatory divergence

We are still very much in the early honeymoon period of the new Government, when flush with a stunning election victory all things seem possible. Even the traditionally hostile Financial Times seems to have been partially won over by the infectious optimism that for now flows through the nation’s veins, warming to some of the opportunities for positive change that Brexit may allow.

Yet at some stage, with the feelgood mood colliding with harsh realities, there is going to be a comedown. The first of these awakenings is likely to centre on trade.

In reaching a trade deal with the EU by the end of the year as promised, the Government will either have to compromise on scope for regulatory divergence, …

The point being that since the divergence is the very thing we want it’s not the thing to compromise upon.

Start from the very basics. There is no version of voluntary trade that is worse than autarky. There are versions of trade that are better than simple unilateral free trade. Like, for example, the other people adopting unilateral free trade too.

So, our baseline starting point for any negotiation on trade is that any trade is better than none, but we must measure any specific proposal against the effects of unilateral free trade. If it would be better to have this extra thing then all well and good, let’s have it. But if the conditions attached to that make the overall deal worse than the unilateral position then we should not have it.

For example, UK farm goods gaining tariff and quota free access to the EU would be a nice thing to have. But a likely cost of that is that British consumers would not be allowed tariff and quota free access to the farm goods of the rest of the world. The cost of that second is greater than the benefits of the first – we don’t do it therefore.

On regulation much the same becomes true. The negotiating stance at least. What would be the paradisical effect of a system of perfect regulation? Not that one exists nor ever will but that’s what we need to imagine. Then, anything we’re asked to accept which is worse than this has to be tested for whether what we lose from the restriction is worth what we then gain elsewhere.

Given EU regulation this is always going to lead to the answer “No”.

November 15, 2019

QotD: Understanding trade policy

You live on a block on Elm St. which has two other households: the Joneses and the Jacksons. Suppose your neighbor Jones puts a knife to your throat and threatens to kill you unless you either buy your tomatoes from him or, if you insist on buying tomatoes from a grower across town, pay him a fine for each across-town tomato that you buy. You immediately understand that Jones is violating your rights; you immediately understand that Jones is a thug, pure and simple. No amount of philosophy, economics, political science, or theology will change your assessment.

Now let Jones secure Jackson’s approval for his actions. Jackson expresses his approval not only of Jones obstructing your freedom to buy across-town tomatoes, Jackson also approves of Jones taking some of your money directly to help Jones pay for the employment, arming, and dressing up in fancy costumes of a street gang who will do the actual dirty work of caging or killing you if you refuse to abide by the tomato-buying terms that Jones imposes on you.

When you object to the injustice of Jones’s actions, he reminds you that you had a vote in this matter. But being outvoted 2 to 1, this majority outcome, by some mystical process, transforms Jones’s pure and simple thuggery into perfectly acceptable – even noble – “trade policy” the violation of which would make you the anti-social criminal.

Further, Jones, to his delight, discovers that Jackson has been hard at work on a treatise that details the many dangers of allowing you to buy your tomatoes without obstruction from across town. Jackson’s treatise even has empirical data on the number of tomatoes and labor hours that would no longer be grown and and worked on your Elm St. block if you are left free to buy your tomatoes unobstructed. Combined with criticisms of “simple-minded” defenses of free trade and with explanations that tomatoes grown across town are sold at unfairly low prices, Jackson’s treatise rids Jones of the few qualms that Jones’s threats of violence against you caused him to suffer from time to time

Thus is “trade policy.”

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2017-10-23.

September 15, 2019

Explaining Brexit to liberal Americans

Andrew Sullivan tries to put the Brexit debate into terms that coastal, urban Americans can understand:

One of the frustrating aspects of reading the U.S. media’s coverage of Brexit is that you’d never get any idea why it happened in the first place. Brexit is treated, automatically, as some kind of pathology, a populist act of wanton self-harm, an absurd idea, etc etc. And from the perspective of an upstanding member of the left-liberal media establishment, that’s all true. If your idea of Britain is formed by jetting in and out of London, a multicultural, global metropolis that is as lively and European as any city on the Continent, you’d think that E.U. membership is a no-brainer. Now that the full hellish economic consequences of exit are in full view, what could possibly be the impulse to stick with it?

I get this. I would have voted Remain. I find London to be far more fun now than it was when I left the place. But allow me to suggest a parallel version of Britain’s situation — but with the U.S. The U.S. negotiated with Canada and Mexico to create a free trade zone called NAFTA, just as the U.K. negotiated entry to what was then a free trade zone called the “European Economic Community” in 1973. Now imagine further that NAFTA required complete freedom of movement for people across all three countries. Any Mexican or Canadian citizen would have the automatic right to live and work in the U.S., including access to public assistance, and every American could live and work in Mexico and Canada on the same grounds. This three-country grouping then establishes its own Supreme Court, which has a veto over the U.S. Supreme Court. And then there’s a new currency to replace the dollar, governed by a new central bank, located in Ottawa.

How many Americans would support this? How many votes would a candidate for president get if he or she proposed it? The questions answer themselves. It would be unimaginable for the U.S. to allow itself to be governed by an entity more authoritative than its own government. It would signify the end of the American experiment, because it would effectively be the end of the American nation-state. But this is precisely the position the U.K. has been in for most of my lifetime. The U.K. has no control over immigration from 27 other countries in Europe, and its less regulated economy has attracted hundreds of thousands of foreigners to work in the country, transforming its culture and stressing its hospitals, schools and transportation system. Its courts ultimately have to answer to the European Court. Most aspects of its economy are governed by rules set in Brussels. It cannot independently negotiate any aspect of its own trade agreements. I think the cost-benefit analysis still favors being a member of the E.U. But it is not crazy to come to the opposite conclusion.

More to the point, the European Economic Community has evolved over the years into something far more ambitious. Through various treaties — Maastricht and Lisbon, for example — what is now called the European Union (note the shift in language) has embarked on a process of ever-greater integration: a common currency, a common foreign policy and now, if Macron has his way, a common central bank. It is requiring the surrender and pooling of more and more national sovereignty from its members. And in this series of surrenders, Britain is unique in its history and identity. In the last century, every other European country has experienced the most severe loss of sovereignty a nation can experience: the occupation of a foreign army on its soil. Britain hasn’t. Its government has retained control of its own island territory now for a thousand years. More salient: this very resistance has come to define the character of the country, idealized by Churchill in the country’s darkest hour. Britain was always going to have more trouble pooling sovereignty than others. And the more ambitious the E.U. became, the more trouble the U.K. had.

August 18, 2019

QotD: “Hitting back” at protectionist policies

You buy lawn-care services from company XYZ located on the other side of town. Your neighbor, Mr. Stump, takes it upon himself to hold you up at gunpoint to the tune of $25 each time you buy services from XYZ rather than from Stump’s teenage son. You are less powerful than Stump and, not being suicidal, you pay the “tariff” that he officiously demands. But Stump is a magnanimous fellow, and so he agrees to a deal with XYZ: Stump drops his tariffs on your purchases from XYZ in return for XYZ agreeing to raise the price it charges you by $15.

But soon a trade dispute erupts. Stump discovers – correctly, we can assume – that XYZ is charging you less for its lawn-care services than Stump agreed is acceptable for you to be charged and that XYZ agreed in the trade deal to charge. Stump, being a master negotiator, threatens to reimpose the $25 tariff on you unless and until XYZ raises the price it charges you to at least the level that Stump has divined is acceptable and that is enshrined in the terms of the trade agreement between him and XYZ. Alas, XYZ gives in and agrees to raise the price it charges you. Stump then boasts that, by not letting XYZ get away with breaking its word in the trade deal, he is not only protecting the neighborhood from dangerously low prices but is also upholding the sacred rule of law and the sanctity of contractual agreements.

Of course, in reality, Stump’s presumptuous exercise of the power to

rob youimpose a tariff on you whenever you engage in commerce that he finds objectionable is a wrong inflicted on you and on your trading partner, XYZ. The fact that the practicalities of the situation result in your and XYZ going along with the “deal” to entice Stump to stop robbing you each time you buy XYZ’s services does not ethically oblige you to stick to the terms of the deal if you can, in secret, get better terms from XYZ. When Stump threatens to reimpose on you the $25 tariff, he harms you. That is, when in response to Stump’s threat to reimpose the tariff XYZ agrees to abide by the terms of its trade agreement with Stump and raise the price that it charges you, you are made worse off, not better off.Stump’s enforcement of this agreement, in short, does not protect you from further victimization in the future; instead, that enforcement is itself an act of victimizing you. Successful enforcement of this agreement assures you a future less prosperous than it would be were Stump instead to ignore XYZ’s “violation” of the deal.

Note: we can all agree that, between the two options (1) $25 tariff and (2) no tariff but an enforced price-hike, under the trade agreement, of $15, that the second option is better for you than the first option. It is in this limited sense that trade agreements in reality are beneficial. But there’s a third option: (3) Stump does not interfere with your commerce and you pay whatever price you negotiate with XYZ without that price being artificially affected by Stump’s interference. This third option is, for you, the best of the three – and it’s the only fully ethical one of the bunch. (So when Dan Griswold, myself, and other free-traders defend trade agreements, we do so with the realistic recognition that option (3) is politically infeasible. Given this unfortunate infeasibility of option (3), we endorse option (2) over option (1).)

Don Boudreaux, “Strict Enforcement of an Impoverishing Deal Assures Continuing Impoverishment”, Café Hayek, 2017-07-07.

July 26, 2019

Post-Brexit, consider CANZUK

Tom Colsey explains why in a post-Brexit world, CANZUK might be an attractive economic alternative:

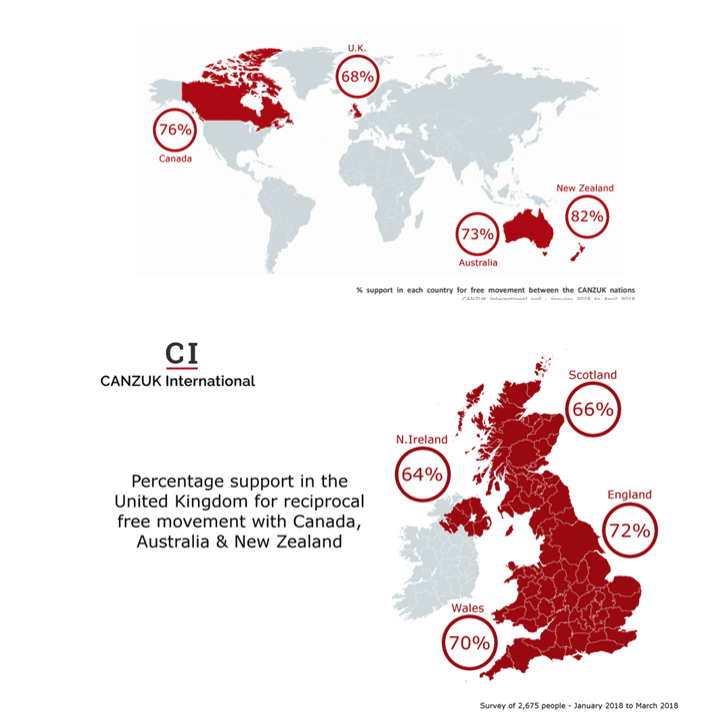

One possible option would mean the island nation would initially turn away from Europe toward certain anglophone Commonwealth nations and former colonies. I talk, of course, of the promising CANZUK proposal that would see Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom band together with voluntary agreements on multilateral free trade and movement, forming a bloc that would singularly hold the third largest nominal GDP in the world.

The Free Movement Proposal

What makes CANZUK unique is how viable and well-thought-out it is on every level. Unlike within the EU, the grouping would not be consolidated through impositional treaties laced with unpleasant footnotes delegating political power to a bureaucratic institution. Freedom of movement would assist meeting labor market demands across the countries, yet this would be prohibited to those with serious criminal records.

Everything the EU seemed to get wrong about forming unions under a liberal-internationalist pretense, CANZUK proposals seem to get right. They account for social attitudes and the dangers of becoming impositional, eroding national sovereignty. Free movement within the European Union had been widely reviled by the domestic population — and is part of the reason Britain now is set to leave. Yet the very same population overwhelmingly favor the same principle, alternatively implemented, across the CANZUK nations, polling outright majorities in favor in every region.

Perhaps a reason for this is that while the nations are extremely close culturally, they are also resoundingly similar socio-economically. Despite their distances, the states could have been separated at birth (of course, they do share the same monarch).

June 22, 2019

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

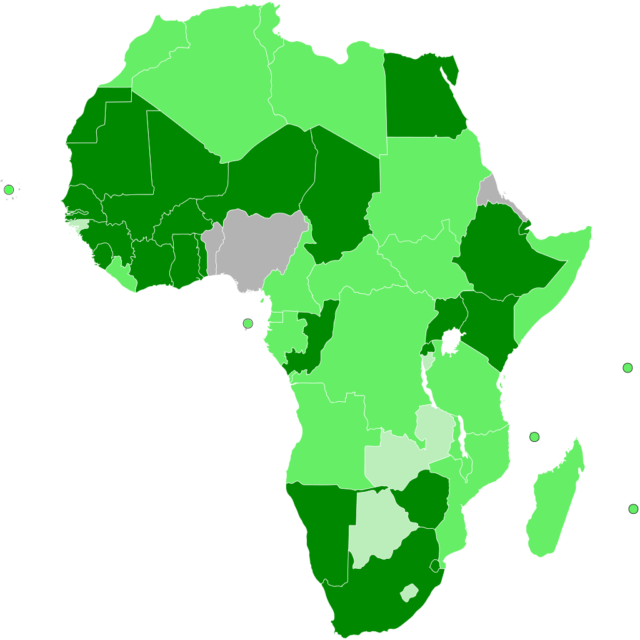

Alexander Hammond explains why a free trade deal among many African nations is good news for the United States and other non-African nations:

2018 map showing the African countries involved in the African Continental Free Trade Agreement.

Dark green indicates ratification, medium green are countries that signed in March 2018, and light green are countries that signed in July 2018 but did not ratify the agreement immediately.

Map by Themightyquill at Wikimedia Commons.

The poorest continent in the world is about to lend a hand to the United States. Last week, Africa implemented the world’s largest free-trade area, and that’s great news for American foreign policy. Back in December, U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton unveiled a plan for the Trump administration’s titled the “Africa Strategy.”

The plan is simple — the United States will give less aid to Africa, instead prioritizing enhancing America’s “economic ties with the region.” Now that many African nations have unified under a single market, trading with the continent will become far easier — and a trade deal between the United States and Africa would help out everyone involved.

Streamlining Trade

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) trade deal officially came into force on May 30, a month after it reached the twenty-two-nation threshold needed to do so. Now, tariffs on 90 percent of the goods traded among AfCFTA member states will be removed — a move that, according to the UN, will boost intra-African trade by 52 percent in only a few years.

Given the United States’ new plans for the continent, the AfCFTA’s member states aren’t the only economies that will reap the benefits of an African single market.

A key component of the Trump administration’s Africa Strategy is to advance “U.S. trade and commercial ties” with Africa by creating “modern comprehensive trade agreements.” A single African market will be a far simpler trade partner for America. Now, only one set of trade deals will need to be negotiated with the AfCFTA — as opposed to fifty-five intricately-crafted trade deals with each small African economy. The U.S. Trade Representative has even released a report noting how time-consuming and costly it is to negotiate trade deals with each African nation. Because trade deals are long and expensive processes, creating a solitary trade deal with the AfCFTA will keep more money in the U.S. government’s purse.

June 12, 2019

The fantastic notion that Donald Trump is “at heart really a free trader”

Guest-posting at Catallaxy Files, Don Boudreaux explodes the farcical notion that President Trump is using protectionist tools with an eventual free trade goal:

Donald Trump addresses a rally in Nashville, TN in March 2017.

Photo released by the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

In the case of Donald Trump, the claim that he is at heart really a free trader who raises tariffs today with the aim of bringing about lower tariffs tomorrow — and all because he is committed to achieving free traders’ ideal goal of maximum possible expansion of the international division of labor — is especially preposterous.

Trump has pontificated on trade for decades, and every word out of his mouth clearly reveals a man who knows nothing about the economics of trade and who is as clichéd an economic nationalist as can be imagined.

Behold this line from a 1990 interview he did in Playboy: “The Japanese double-screw the US, a real trick: First they take all our money with their consumer goods, then they put it back in buying all of Manhattan. So either way, we lose.”

Let’s examine this unalloyed gem of economic witlessness.

Overlooking Trump’s outrageous exaggerations, such as his claim that the Japanese buy up “all” of Manhattan, we start by stating an obvious truth: the voluntary purchase of a good is not a transaction in which the buyer is “screwed” or has his or her money “taken.” Instead, the buyer’s money is voluntarily spent. While every person of good sense sees a foreign seller who makes attractive offers to domestic buyers as someone who improves the well-being of each buyer who accepts the offer, Trump sees this seller as a con artist or thief.

And so Trump ignores the value to Americans of the imports we purchase. In typical mercantilist fashion, he believes that the ultimate purpose of trade is to send out as many exports as possible in exchange for as much money as possible — money that in Trump’s ideal world is never spent on imports. His view on this matter is even more bizarre than that of ordinary mercantilists. For Trump, imports are not merely costs that we endure in order to export, they are actual losses. (Although it goes without saying, I’ll say it nevertheless: Trump does not understand that imports are benefits and that exports are costs.)

Furthermore, by describing the money spent on imports as “our money,” Trump reveals his belief that money earned by each American does not belong to that individual but, instead, to the collective.

Also in the fashion of the typical mercantilist, the presumption is that the nation is akin to a gigantic household whose members all share in and collectively own its money. And just as Dad justly superintends little Emma’s and Bobby’s spending to ensure that they don’t dissipate the family’s wealth, Uncle Sam must superintend his subjects’ spending in order to ensure that we don’t dissipate the nation’s wealth.

One other flaw in the above quotation from Trump’s Playboy interview is notable: he believes that foreign investments in America inflict losses on us. He doesn’t pause to consider that when we Americans sell assets to foreigners we regain ownership of some of the dollars that Trump, in his previous sentence, lamented are lost to Americans when we bought imports.

Nor does he ask what the American sellers of these assets do with the sales proceeds. Perhaps we invest some or even all of them. And if so, perhaps these new American investments will prove to be more profitable than are the investments made in America by foreigners. (By the way, contrary to another mercantilist myth, Americans are not made better off when foreigners’ investments in America fail. Quite the contrary.)

An even deeper error infects Trump’s “understanding” of foreign investment: he implicitly — and, once again, like all mercantilists — assumes that the amount of capital in the world is fixed. Only then would it be true that each American sale of assets to foreigners necessarily reduces Americans’ net financial worth (which is presumably what Trump means when he says that “we lose” when the Japanese purchase Manhattan real estate).

December 6, 2018

QotD: The best “industrial policy” is not to have one at all

Which brings us to nub of the matter: how do we increase trade and productivity, given that productivity is the thing they claim the whole schemozzle is about. There is one simple and single policy which will do both. One policy which will increase British productivity simply by allowing more trade.

This policy is so simple that even the Treasury (yes, that’s our Treasury, the one in London) was able to get right, even when being run by George Osborne. As they set out in their analysis of Brexit repercussions:

“The benefits of trade in terms of increasing productivity are well understood… greater openness to trade creates a larger market which the most productive firms expand to serve. Openness also increases competition between firms, enhancing the incentives for domestic firms to innovate or adopt new technology… It increases returns on investment, and encourages UK firms to make greater use of new technologies, either by improving the quality of inputs, or through the more effective adoption of technological innovations. Greater openness to trade also increases consumer choice and reduces prices. Lower trade costs give consumers access to cheaper imported goods and competition reduces the price of domestically-produced goods.”

In plain English, it is the competition from imports which forces British firms to buck up their act and become more productive. So here is how we improve British productivity: we move to unilateral free trade. No barriers to imports, no tariffs, just the same regulation as domestically produced items.

British industry, facing the stiffest competition from the best in the world, would be forced to meet global standards of productivity. So the best industrial policy would be to stop trying to have an industrial policy about what we can and can’t buy from beyond Britain’s borders – and the rest should take care of itself.

Tim Worstall, “The best industrial strategy for Britain is not to have one”, CapX, 2017-01-23.

November 22, 2018

QotD: They’re not “trade wars”, they’re “economic suicide bombings”

… this recent Facebook post by Steve Horwitz:

Instead of “trade wars,” let’s call them what they really are: economic suicide bombings.

Indeed so.

Like physical bombings, the economic suicide bombings that are tariffs and other trade restrictions create particular jobs by destroying real wealth. Those who then resupply the wealth that is destroyed applaud the suicide bombings, and tirelessly repeat ancient, absurd dogmas to justify the bombings. But unlike physical bombings, the victims of economic suicide bombings are largely unseen and, hence, ignored.

The people – and they are many – who cling to the dogma of protectionism do so as a matter of faith. This dogma cannot withstand the scrutiny of reason or be justified by any competent observation of reality. Yet the uncivilized and destructive religion of protectionism nevertheless flourishes, no doubt in no small part because the narrow interests of a relatively small but politically powerful cabal of producers are served by the public taking to be true all the mysticism of protectionism and its alleged miracles.

Whether or not Jesus miraculously created abundance out of the scarcity of five loaves and two fish I will not here say. I am, however, quite confident that when the likes of Donald Trump, Peter Navarro, Chuck Schumer, Bernie Sanders, and Sherrod Brown promise to perform a similar miracle – that is, to create abundance out of artificially contrived scarcity – they are either delusional about their own powers or are cynically playing their congregations for fools.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2018-10-12.

November 14, 2018

QotD: Protectionism and competition

The ITC [U.S. International Trade Commission] acts as if American companies have a right not to be injured by foreign competition, regardless of how poorly they serve their American customers.

James Bovard, The Fair Trade Fraud, 1991.