I was aware that the greatest Liberal Prime Minister in Canadian history, Sir Wilfred Laurier, had lost an election on the basis of a negotiated free trade deal with the United States, but I was not aware of exactly how that happened. Colby Cosh provides the gory details that got Laurier out of office for good:

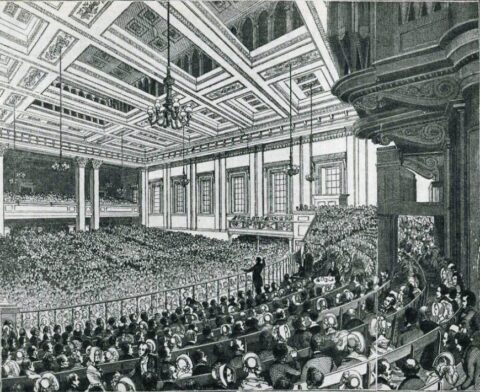

Funny thing I noticed: Friday marked the anniversary of the 20th century’s most remarkable explosion in Canadian-American relations, which took place on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1911. On that day, Feb. 14, Missouri Democratic congressman James Beauchamp “Champ” Clark gave a short speech in defence of a free-trade agreement that had been hammered out between the (Republican) Taft administration and Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government.

Clark, a progressive and witty westerner who had already been chosen to become Speaker of the House in April, was widely expected to be the Democratic nominee for president in 1912. He was, in other words, a man who counted. And on the floor of the House, he advocated passage of the free-trade deal on grounds that eventually doomed it: namely, that it was a conscious step toward total American absorption of the Dominion of Canada.

When Clark’s remarks hit the newspapers up north — and no news story hit harder between 1900 and the dawn of the Great War — there was a spasm of anti-American and pro-Empire feeling throughout the country. As any schoolbook will tell you, this helped lead to the defeat of Laurier and the ruin of the trade deal in September 1911’s general election. This gaffe is indeed now what Clark is best remembered for, along with his eventual fumbling away of the 1912 presidential nomination to an unassuming professor named Woodrow Wilson.

When I was an undergraduate, we all had to have it explicitly explained to us that back in Edwardian days, the Liberals were the party of free trade, and the Conservatives the great defenders of tariff protection (although Sir John A. had sometimes sought without success to kick-stark “reciprocity” negotiations with the U.S.). Perhaps the most confusing feature of the 1911 controversy to students of today will be Champ Clark’s idea that the U.S. government would want to lower trade barriers to facilitate eventual annexation of Canada, rather than raising them to mutually punitive levels as a matter of crude antagonism.

Between Confederation and Champ’s time, Americans often just assumed as a matter of course that Canada would fall into their laps without any need for aggression or invasion. We northerners would eventually see that the benefits of American citizenship were more valuable than our romantic imperial attachments, and we would come beat down the door. This was certainly Clark’s own idea, and it created no controversy among Americans themselves when he expressed it.

Of course, in Laurier’s day “liberal” meant something closer to the modern sense of “libertarian” than it does to the current incarnation (or shambling corpse) of that party.