After 1918 there began to appear something that had never existed in England before: people of indeterminate social class. In 1910 every human being in these islands could be “placed” in an instant by his clothes, manners and accent. That is no longer the case. Above all, it is not the case in the new townships that have developed as a result of cheap motor cars and the southward shift of industry. The place to look for the germs of the future England is in the light-industry areas and along the arterial roads. In Slough, Dagenham, Barnet, Letchworth, Hayes – everywhere, indeed, on the outskirts of great towns – the old pattern is gradually changing into something new. In those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick the sharp distinctions of the older kind of town, with its slums and mansions, or of the country, with its manor-houses and squalid cottages, no longer exist. There are wide gradations of income, but it is the same kind of life that is being lived at different levels, in labour-saving flats or council houses, along the concrete roads and in the naked democracy of the swimming-pools. It is a rather restless, cultureless life, centring round tinned food, Picture Post, the radio and the internal combustion engine. It is a civilization in which children grow up with an intimate knowledge of magnetoes and in complete ignorance of the Bible. To that civilization belong the people who are most at home in and most definitely of the modern world, the technicians and the higher-paid skilled workers, the airmen and their mechanics, the radio experts, film producers, popular journalists and industrial chemists. They are the indeterminate stratum at which the older class distinctions are beginning to break down.

This war, unless we are defeated, will wipe out most of the existing class privileges. There are every day fewer people who wish them to continue. Nor need we fear that as the pattern changes life in England will lose its peculiar flavour. The new red cities of Greater London are crude enough, but these things are only the rash that accompanies a change. In whatever shape England emerges from the war it will be deeply tinged with the characteristics that I have spoken of earlier. The intellectuals who hope to see it Russianized or Germanized will be disappointed. The gentleness, the hypocrisy, the thoughtlessness, the reverence for law and the hatred of uniforms will remain, along with the suet puddings and the misty skies. It needs some very great disaster, such as prolonged subjugation by a foreign enemy, to destroy a national culture. The Stock Exchange will be pulled down, the horse plough will give way to the tractor, the country houses will be turned into children’s holiday camps, the Eton and Harrow match will be forgotten, but England will still be England, an everlasting animal stretching into the future and the past, and, like all living things, having the power to change out of recognition and yet remain the same.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

December 7, 2021

QotD: The decline of class distinctions in Britain

December 4, 2021

When King James VI became King James I and VI

In his latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes discusses how the King of Scotland succeeded to the English throne as well:

King James I (of England) and VI (of Scotland)

Portrait by Daniel Myrtens, 1621 from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s late March 1603, and an exhausted messenger arrives in Edinburgh bearing a sapphire ring. He has ridden for over two days straight, over hundreds of miles, and his hair and clothes are matted with blood — on the way he had fallen from his horse, a hoof striking him directly in the head. It’s a miracle he’s alive, but he knows it has been worth it. He is the very first to tell you that your childless first cousin twice removed — the killer of your mother, whom you never knew — is finally dead. You, King James VI of Scotland, are James I of England as well.

[…]

James’s accession was a frenzy. From the very moment of Elizabeth’s death, her entire patronage network was turned on its head. Her chief ministers, the Privy Council, were relatively safe. Some of them had been corresponding with James for years. But they could only look on, anxiously, as a rush of would-be cronies went north to meet their new king. The exhausted messenger with the sapphire ring, Sir Robert Carey, was just the first. Carey had been related to Elizabeth I on her mother’s side — he was her first cousin once removed. (Carey’s grandmother was the “other Boleyn girl”, played by Scarlett Johansson in the 2008 film — although there’s no solid evidence, it’s not totally impossible that Carey was actually related to Elizabeth on her father’s side instead …) But that family connection meant nothing now that the queen was dead.

The sudden reset of the source of all patronage meant that the earlier the access to the new king’s person, the greater the chance of gaining his favour. Carey may have angered the Privy Council by riding ahead of their formal letters to James, but his exertion won him an on-the-spot appointment as a gentleman of the bedchamber, and his wife became a lady in waiting to James’s queen. The Careys were soon charged with the care of the royal couple’s younger sickly child, and when that child eventually became Charles I, Carey was made Earl of Monmouth. Not a bad result for a head wound and a two days’ ride, though I’m sure the horses would disagree. An old proverb about England was that it was “a paradise for women, a purgatory for servants, and a hell for horses” — something that James’s accession really put to the test. One teenage noblewoman reported how she and her mother killed three horses in a single day, pushing them hard despite the heat, in their rush to meet the new queen.

Just as courtiers flocked to James, however, the king wanted to win friends and allies too. So he handed out favours like confetti. Before he had even reigned a single year, he had created 934 knighthoods — already more than the 878 that Elizabeth I, her generals, and her lord deputies in Ireland had created over the course of her entire 45-year reign. One morning, during his journey down to London, James knighted more people than Elizabeth had in her first five years — all before he’d even had his breakfast. The sheer volume of new knighthoods prompted Francis Bacon — one of about 300 to be knighted in London ahead of the coronation — to call it a “divulged and almost prostitute title”.

The same went for peerages. Elizabeth, over her long reign of almost half a century, had created only 18 new titles. James, before he had even been crowned, had already created 12 — mostly turning knights into lords, and raising some lords into earls. Along with the honours came grants of land, annual pensions, and one-off gifts — not only to James’s new English courtiers, but to his old Scottish favourites too. James’s arrival was an explosion of largesse. (Not all were happy about the relative loss of favour, of course […] at least one pro-invention courtier got involved in a treasonous plot against the new king and ended up losing his head.)

James’s largesse even extended to policy. As he triumphantly marched into London, he issued a proclamation to immediately suspend all of Elizabeth’s patent monopolies, to be re-granted pending review. (This did not apply to patents for trading corporations or guilds.) Rather than leaving the validity of patents to be tested in the common-law courts, at great legal cost to those affected, he would have his Privy Council systematically examine them first, only allowing them if they were in the public interest. He characterised it as a continuation — even a “perfecting” — of Elizabeth’s partial measures a couple of years earlier, which we discussed in Part II. With his proclamation also condemning various other unpopular things, like high court fees, his new subjects were overjoyed.

But the honeymoon was not to last.

November 29, 2021

QotD: The law

Here one comes upon an all-important English trait: the respect for constitutionalism and legality, the belief in “the law” as something above the State and above the individual, something which is cruel and stupid, of course, but at any rate incorruptible.

It is not that anyone imagines the law to be just. Everyone knows that there is one law for the rich and another for the poor. But no one accepts the implications of this, everyone takes it for granted that the law, such as it is, will be respected, and feels a sense of outrage when it is not. Remarks like “They can’t run me in; I haven’t done anything wrong”, or “They can’t do that; it’s against the law”, are part of the atmosphere of England. The professed enemies of society have this feeling as strongly as anyone else. One sees it in prison-books like Wilfred Macartney’s Walls Have Mouths or Jim Phelan’s Jail Journey, in the solemn idiocies that take place at the trials of Conscientious Objectors, in letters to the papers from eminent Marxist professors, pointing out that this or that is a “miscarriage of British justice”. Everyone believes in his heart that the law can be, ought to be, and, on the whole, will be impartially administered. The totalitarian idea that there is no such thing as law, there is only power, has never taken root. Even the intelligentsia have only accepted it in theory.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

November 27, 2021

King James I and his hatred of tobacco smoking — “so vile and stinking a custom”

Anton Howes recounts some stories he uncovered while researching English patent and monopoly policies during the Elizabethan and Stuart eras:

… some of the most interesting proclamations to catch my eye were about tobacco. Whereas tobacco was famously a New World crop, it is actually very easy to grow in England. Yet what the proclamations reveal is that the planting of tobacco in England and Wales was purposefully suppressed, and for some very interesting reasons.

James I was an anti-tobacco king. He even published his own tract on the subject, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, just a year after his succession to the English throne. Yet as a result of his hatred of “so vile and stinking a custom”, imports of tobacco were heavily taxed and became a major source of revenue. Somewhat ironically, the cash-strapped king became increasingly financially dependent on the weed he never smoked. The emergence of a domestic growth of tobacco was thus not only offensive to the king on the grounds that he thought it a horrid, stinking, and unhealthy habit — it was also a threat to his income.

What I was most surprised to see, however, was just how explicitly the king admitted this. It’s usual, when reading official proclamations, to have to read between the lines, or to have to track down the more private correspondence of his ministers. Very often James’s proclamations would have an official justification for the public good, while in the background you’ll find it originated in a proposal from an official about how much money it was likely to raise. There was money to be made in making things illegal and then collecting the fines.

Yet the 1619 proclamation against growing tobacco in England and Wales had both. The legendary Francis Bacon, by this stage Lord High Chancellor, privately noted that the policy might raise an additional £3,000 per year in customs revenue. And the proclamation itself noted that growing tobacco in England “does manifestly tend to the diminution of our customs”. Although the proclamation notes that the loss of customs revenue was not usually a grounds for banning things, as manufactures and necessary commodities were better made at home than abroad, “yet where it shall be taken from us, and no good but rather hurt thereby redound to our people, we have reason to preserve”. Fair enough.

And that’s not all. James in his proclamation expressed all sorts of other worries about domestic tobacco. Imported tobacco, he claimed, was at least only a vice restricted to the richer city sorts, where it was already an apparent source of unrest (presumably because people liked to smoke socially, gathering into what seemed like disorderly crowds). With tobacco being grown domestically, however, it was “begun to be taken in every mean village, even amongst the basest people” — an even greater apparent threat to social order. James certainly wasn’t wrong about this wider adoption. Just a few decades later, a Dutch visitor to England reported that even in relatively far-flung Cornwall “everyone, men and women, young and old, puffing tobacco, which is here so common that the young children get it in the morning instead of breakfast, and almost prefer it to bread.”

[…]

Indeed, policymakers thought that the domestic production of tobacco would actively harm one of their key economic projects: the development of the colonies of Virginia and the Somers Isles (today known as Bermuda). Although James I hoped that their growth of tobacco would be only a temporary economic stop-gap, “until our said colonies may grow to yield better and more solid commodities”, he believed that without tobacco the nascent colonial economies would never survive. Banning the domestic growth of tobacco thus became an essential part of official colonial policy — one that was continued by James’s successors, who did not always share his more general hatred of smoking. Although the other justifications for banning domestic tobacco would soon fall away, that of maintaining the colonies — backed by an increasingly wealthy colonial lobby — was the one that prevailed.

November 26, 2021

QotD: English working class culture

… in all societies the common people must live to some extent against the existing order. The genuinely popular culture of England is something that goes on beneath the surface, unofficially and more or less frowned on by the authorities. One thing one notices if one looks directly at the common people, especially in the big towns, is that they are not puritanical. They are inveterate gamblers, drink as much beer as their wages will permit, are devoted to bawdy jokes, and use probably the foulest language in the world. They have to satisfy these tastes in the face of astonishing, hypocritical laws (licensing laws, lottery acts, etc., etc.) which are designed to interfere with everybody but in practice allow everything to happen. Also, the common people are without definite religious belief, and have been so for centuries. The Anglican Church never had a real hold on them, it was simply a preserve of the landed gentry, and the Nonconformist sects only influenced minorities. And yet they have retained a deep tinge of Christian feeling, while almost forgetting the name of Christ. The power-worship which is the new religion of Europe, and which has infected the English intelligentsia, has never touched the common people. They have never caught up with power politics. The “realism” which is preached in Japanese and Italian newspapers would horrify them. One can learn a good deal about the spirit of England from the comic coloured postcards that you see in the windows of cheap stationers’ shops. These things are a sort of diary upon which the English people have unconsciously recorded themselves. Their old-fashioned outlook, their graded snobberies, their mixture of bawdiness and hypocrisy, their extreme gentleness, their deeply moral attitude to life, are all mirrored there.

The gentleness of the English civilization is perhaps its most marked characteristic. You notice it the instant you set foot on English soil. It is a land where the bus conductors are good-tempered and the policemen carry no revolvers. In no country inhabited by white men is it easier to shove people off the pavement. And with this goes something that is always written off by European observers as “decadence” or hypocrisy, the English hatred of war and militarism. It is rooted deep in history, and it is strong in the lower-middle class as well as the working class. Successive wars have shaken it but not destroyed it. Well within living memory it was common for “the redcoats” to be booed at in the streets and for the landlords of respectable public-houses to refuse to allow soldiers on the premises. In peace-time, even when there are two million unemployed, it is difficult to fill the ranks of the tiny standing army, which is officered by the country gentry and a specialized stratum of the middle class, and manned by farm labourers and slum proletarians. The mass of the people are without military knowledge or tradition, and their attitude towards war is invariably defensive. No politician could rise to power by promising them conquests or military “glory”, no Hymn of Hate has ever made any appeal to them. In the last war the songs which the soldiers made up and sang of their own accord were not vengeful but humorous and mock-defeatist. The only enemy they ever named was the sergeant-major.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

November 18, 2021

When artillery became powerful enough to literally destroy castles

In Quillette, Paul Lockhart recounts one of the early artillery successes in European siege warfare, the reduction of the English-held fortifications at Odruik:

Portrtait of Philip the Bold (Philip II, Duke of Burgundy), 1342-1404.

Unknown painter of the Flemish School via Wikimedia Commons.

Philip the Bold, duke of Burgundy, was a warrior’s warrior. Hawk-nosed, ambitious, and brash, Philip had been a soldier since childhood. He was still a smooth-faced boy of 14 when he fought alongside his father, King John II of France, in the battle of Poitiers in 1356. Like King John, he was taken prisoner by the English when Edward, the Black Prince of Wales, vanquished the French on the field at Poitiers. A decade later, the duke, always looking for an advantage over the Englishmen who had invaded his country, embraced a novel technology: gunpowder.

This mysterious Asian invention had been known in Europe for more than a century, and for nearly that long European armies had used it as a weapon of war — or, more precisely, as the substance that made another recent innovation, the cannon, work. So far, gunpowder artillery had not shown great promise. Cannon had been used as siege engines in European warfare at least as early as the 1320s. But for all the trouble and effort they demanded, they had not proven themselves to be much more effective than conventional siege weapons such as catapults and trebuchets, machines that used mechanical energy to hurl projectiles at castle walls. Certainly, the early cannon did not appear to be effective enough to justify their cost, which was substantial.

But Philip the Bold saw promise in the new weapons, especially the huge siege guns that came to be known as bombards, and in 1369 he began to invest heavily in them. France and England were then locked in the on-again, off-again series of dynastic conflicts known today as the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453). In 1377, when Duke Philip’s brother and sovereign, King Charles V of France, ordered him to attack the English in the Calais region, the duke answered the call, bringing with him more than 100 new cannon, including one monster of a gun that fired a stone cannonball weighing some 450 livres (around 485 pounds).

One of the duke’s intended targets was the English-held castle at Odruik, built with stout masonry walls and surrounded by a thick layer of outworks. Odruik would be a tough nut to crack. Its defenders seemed to think so, too, and were confident that they could hold out against Duke Philip’s army, even as the duke’s men began to put their huge siege cannon into position in full view of the castle walls.

The first few shots from Philip’s siege-battery hammered Odruik’s outer walls into dust. Soon, the stone cannonballs were sailing through the walls as if they weren’t there; soon after that, the outer walls actually weren’t there. After Philip’s guns had fired a grand total of about 200 rounds, much of Odruik’s once-proud walls lay in ruin, and before the duke could send his men through the breach and into the castle, Odruik’s defenders capitulated.

Philip the Bold’s triumph at Odruik in 1377 was a harbinger of things to come, a revealer of unsettling truths. Gunpowder artillery had been used in sieges before, but Odruik was its first overwhelming and clear-cut victory over a castle. The siege of Odruik demonstrated that — when the guns were big enough, and when there were enough of them — cannon were more powerful than any siege engine yet invented, and could knock down castles in a matter of hours. What happened at Odruik would be repeated over and over again at castles throughout continental Europe and the British Isles through the remainder of the Middle Ages and beyond.

It was one of the accepted “rules” of war that a besieged town that surrendered before the beseiging army conducted an infantry assault would be spared from sack … the theory being that once the fortifications had been overcome, the final outcome was not in doubt and the defenders lost no honour from the surrender. You can certainly understand why the citizens of the defended town would be eager to avoid the plunder and rapine of an assaulting army once the walls were breached.

November 15, 2021

QotD: Britain at war

England is the most class-ridden country under the sun. It is a land of snobbery and privilege, ruled largely by the old and silly. But in any calculation about it one has got to take into account its emotional unity, the tendency of nearly all its inhabitants to feel alike and act together in moments of supreme crisis. It is the only great country in Europe that is not obliged to drive hundreds of thousands of its nationals into exile or the concentration camp. At this moment, after a year of war, newspapers and pamphlets abusing the Government, praising the enemy and clamouring for surrender are being sold on the streets, almost without interference. And this is less from a respect for freedom of speech than from a simple perception that these things don’t matter. It is safe to let a paper like Peace News be sold, because it is certain that ninety-five per cent of the population will never want to read it. The nation is bound together by an invisible chain. At any normal time the ruling class will rob, mismanage, sabotage, lead us into the muck; but let popular opinion really make itself heard, let them get a tug from below that they cannot avoid feeling, and it is difficult for them not to respond. The left-wing writers who denounce the whole of the ruling class as “pro-Fascist” are grossly over-simplifying. Even among the inner clique of politicians who brought us to our present pass, it is doubtful whether there were any conscious traitors. The corruption that happens in England is seldom of that kind. Nearly always it is more in the nature of self-deception, of the right hand not knowing what the left hand doeth. And being unconscious, it is limited. One sees this at its most obvious in the English Press. Is the English press honest or dishonest? At normal times it is deeply dishonest. All the papers that matter live off their advertisements, and the advertisers exercise an indirect censorship over news. Yet I do not suppose there is one paper in England that can be straightforwardly bribed with hard cash. In the France of the Third Republic all but a very few of the newspapers could notoriously be bought over the counter like so many pounds of cheese. Public life in England has never been openly scandalous. It has not reached the pitch of disintegration at which humbug can be dropped.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

November 3, 2021

QotD: English literature

Here one comes back to two English characteristics that I pointed out, seemingly rather at random, at the beginning of the last chapter. One is the lack of artistic ability. This is perhaps another way of saying that the English are outside the European culture. For there is one art in which they have shown plenty of talent, namely literature. But this is also the only art that cannot cross frontiers. Literature, especially poetry, and lyric poetry most of all, is a kind of family joke, with little or no value outside its own language-group. Except for Shakespeare, the best English poets are barely known in Europe, even as names. The only poets who are widely read are Byron, who is admired for the wrong reasons, and Oscar Wilde, who is pitied as a victim of English hypocrisy. And linked up with this, though not very obviously, is the lack of philosophical faculty, the absence in nearly all Englishmen of any need for an ordered system of thought or even for the use of logic.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

October 30, 2021

QotD: Britain as a nation

I have spoken all the while of “the nation”, “England”, “Britain”, as though 45 million souls could somehow be treated as a unit. But is not England notoriously two nations, the rich and the poor? Dare one pretend that there is anything in common between people with £100,000 a year and people with £1 a week? And even Welsh and Scottish readers are likely to have been offended because I have used the word “England” oftener than “Britain”, as though the whole population dwelt in London and the Home Counties and neither north nor west possessed a culture of its own.

One gets a better view of this question if one considers the minor point first. It is quite true that the so-called races of Britain feel themselves to be very different from one another. A Scotsman, for instance, does not thank you if you call him an Englishman. You can see the hesitation we feel on this point by the fact that we call our islands by no less than six different names, England, Britain, Great Britain, the British Isles, the United Kingdom and, in very exalted moments, Albion. Even the differences between north and south England loom large in our own eyes. But somehow these differences fade away the moment that any two Britons are confronted by a European. It is very rare to meet a foreigner, other than an American, who can distinguish between English and Scots or even English and Irish. To a Frenchman, the Breton and the Auvergnat seem very different beings, and the accent of Marseilles is a stock joke in Paris. Yet we speak of “France” and “the French”, recognizing France as an entity, a single civilization, which in fact it is. So also with ourselves. Looked at from the outside, even the cockney and the Yorkshireman have a strong family resemblance.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

October 23, 2021

The English Statute of Monopolies gets far more credit than it actually deserves

The Statute of Monopolies (1624) is often said to have been critical in helping to start England on the road to the Industrial Revolution, but in the latest Age of Invention newsletter Anton Howes argues it is far more complicated than it seems:

Letters Patent Issued by Queen Victoria, 1839. On 15 June 1839 Captain William Hobson was officially appointed by Queen Victoria to be Lieutenant Governor General of New Zealand. Hobson (1792 – 1842) was thus the first Governor of New Zealand.

Constitutional Records group of Archives NZ via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most frequently mentioned landmarks in the history of intellectual property is the Statute of Monopolies, passed by the English parliament in 1624. I’ve often seen it lauded as the beginning of the system of patents for invention, or the first patent law. I remember giving a talk a few years ago where I downplayed the role of formal institutions in encouraging the Industrial Revolution, prompting an outraged economist in the audience to point to the law as a sort of gotcha — “here’s a better explanation: with patents you incentivise invention, and the Brits had just invented patents”.

Which is all to illustrate that the Statute of Monopolies is often fundamentally misunderstood. So what, exactly, did it actually do? It’s a tale of opportunism, corruption, and court intrigue, with some actual innovation inbetween. The whole saga ended Francis Bacon’s political career, led to a major constitutional crisis, and set the scene for how inventors were to behave and act for well over a century. In this first part, I’ll give the context you’ll need to really appreciate what was going on, and I’ll publish the rest in the weeks to come.

First off, the Statute of Monopolies was certainly not the first patent law. Venice’s senate had enacted a law on monopolies for invention as early as 1474. But even then, we shouldn’t be looking for statutes at all. The history of patents does not begin in 1474, but much earlier, with plenty of monopolies over new inventions having already been granted by the ruling grand council of Venice, and by the authorities of other Italian cities like Florence. The key thing to recognise about early patents is that they were not a creation of parliaments or their statutes, but of those in charge. They were the creation of sovereigns, a creature of kings and queens (or in the case of republics like Venice, of governing councils).

As regular readers of this newsletter might remember, patent monopolies for invention had already had long history in England, well before 1624. Patents in general were a very ordinary tool of English monarchs, used to communicate their will. By issuing letters patent, monarchs essentially issued public orders, open for everyone to see. (Think “patently”, as in clearly or obvious, which comes from the same root.) Monarchs used letters patent to grant titles and lands, appoint or remove people as officials, extend royal protections to foreign immigrants, incorporate cities, guilds, even theatre troupes — in general, just to rule.

And, eventually, English monarchs copied the Venetians by issuing letters patent to grant temporary monopolies to particular people, to encourage them to make discoveries, publish books, or introduce new industries or inventions to the realm. It’s only over the passage of centuries that we’ve come to refer to patents for invention — a mere subset of letters patent, and really even a mere subset of patent monopolies for all sorts of other creative work — as simply patents. Intellectual property was thus a ruler-granted privilege, created in the same way that a town gains the official status of a city, or a commoner becomes a knight. English monarchs began granting monopolies for discovering new territories and trade routes from 1496, for printing certain books from 1512, and for introducing new industries or inventions from 1552 (with one weird isolated exception from as early as 1449).

October 20, 2021

QotD: The English

National characteristics are not easy to pin down, and when pinned down they often turn out to be trivialities or seem to have no connection with one another. Spaniards are cruel to animals, Italians can do nothing without making a deafening noise, the Chinese are addicted to gambling. Obviously such things don’t matter in themselves. Nevertheless, nothing is causeless, and even the fact that Englishmen have bad teeth can tell something about the realities of English life.

Here are a couple of generalizations about England that would be accepted by almost all observers. One is that the English are not gifted artistically. They are not as musical as the Germans or Italians, painting and sculpture have never flourished in England as they have in France. Another is that, as Europeans go, the English are not intellectual. They have a horror of abstract thought, they feel no need for any philosophy or systematic “world-view”. Nor is this because they are “practical”, as they are so fond of claiming for themselves. One has only to look at their methods of town-planning and water-supply, their obstinate clinging to everything that is out of date and a nuisance, a spelling system that defies analysis, and a system of weights and measures that is intelligible only to the compilers of arithmetic books, to see how little they care about mere efficiency. But they have a certain power of acting without taking thought. Their world-famed hypocrisy – their double-faced attitude towards the Empire, for instance – is bound up with this. Also, in moments of supreme crisis the whole nation can suddenly draw together and act upon a species of instinct, really a code of conduct which is understood by almost everyone, though never formulated. The phrase that Hitler coined for the Germans, “a sleep-walking people”, would have been better applied to the English. Not that there is anything to be proud of in being called a sleep-walker.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

October 15, 2021

QotD: England and the English

When you come back to England from any foreign country, you have immediately the sensation of breathing a different air. Even in the first few minutes dozens of small things conspire to give you this feeling. The beer is bitterer, the coins are heavier, the grass is greener, the advertisements are more blatant. The crowds in the big towns, with their mild knobby faces, their bad teeth and gentle manners, are different from a European crowd. Then the vastness of England swallows you up, and you lose for a while your feeling that the whole nation has a single identifiable character. Are there really such things as nations? Are we not forty-six million individuals, all different? And the diversity of it, the chaos! The clatter of clogs in the Lancashire mill towns, the to-and-fro of the lorries on the Great North Road, the queues outside the Labour Exchanges, the rattle of pin-tables in the Soho pubs, the old maids hiking to Holy Communion through the mists of the autumn morning – all these are not only fragments, but characteristic fragments, of the English scene. How can one make a pattern out of this muddle?

But talk to foreigners, read foreign books or newspapers, and you are brought back to the same thought. Yes, there is something distinctive and recognizable in English civilization. It is a culture as individual as that of Spain. It is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes. It has a flavour of its own. Moreover it is continuous, it stretches into the future and the past, there is something in it that persists, as in a living creature. What can the England of 1940 have in common with the England of 1840? But then, what have you in common with the child of five whose photograph your mother keeps on the mantelpiece? Nothing, except that you happen to be the same person.

And above all, it is your civilization, it is you. However much you hate it or laugh at it, you will never be happy away from it for any length of time. The suet puddings and the red pillar-boxes have entered into your soul. Good or evil, it is yours, you belong to it, and this side the grave you will never get away from the marks that it has given you.

Meanwhile England, together with the rest of the world, is changing. And like everything else it can change only in certain directions, which up to a point can be foreseen. That is not to say that the future is fixed, merely that certain alternatives are possible and others not. A seed may grow or not grow, but at any rate a turnip seed never grows into a parsnip. It is therefore of the deepest importance to try and determine what England is, before guessing what part England can play in the huge events that are happening.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.

October 11, 2021

The Darien Venture: The Colony that Bankrupted Scotland

Geographics

Published 14 Nov 2019If a Nation’s wealth and power were to be measured in stubbornness, resilience, and inventiveness, rather than GDP, Scotland would be a top-5 superpower. The people that brought to you televisions, refrigerators, penicillin, and gin & tonic have gone through many a rough patch throughout their history. Very often, hard times were related to their rocky relationship with their Southern neighbours, the English.

Credits:

Host – Simon Whistler

Author – Arnaldo Teodorani

Producer – Jennifer Da Silva

Executive Producer – Shell HarrisBusiness inquiries to admin@toptenz.net

October 9, 2021

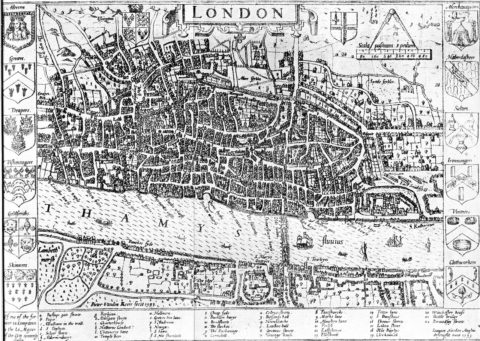

The incredible growth of London after 1550

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers some alternative explanations for London’s spectacular growth beginning in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I:

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

As regular readers will know, I’ve lately been obsessed with England’s various economic transformations between 1550 and 1650 — the dramatic eightfold growth of London, in particular, and the fall in the proportion of workers engaged in agriculture despite the growth of the overall population.

As I’ve argued before, I think that the original stimulus for many of these changes was the increased trading range of English overseas merchants. Thanks to advances in navigational techniques, they were able to find new markets and higher prices for their exports, particularly in the Mediterranean and then farter afield. And they were able to buy England’s imports much more cheaply, by going directly to their source. Although the total value of imports rose dramatically — by 150% in just 1600-38 — the value of exports seems to have risen by even more, as there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that for most of the period England had a trade surplus. The supply of money increased, even though Britain had no major gold or silver mines of its own.

The growing commerce was the major spur to London’s growth, with English merchants spending their profits in the city, and ever-cheaper and more varied luxury imports enticing the nobility from their country estates. Altogether, the concentration of people and wealth in London must have resulted in all sorts of spill-over effects to further drive its growth. After the initial push from overseas trade, I suspect that by the late seventeenth century the city was large enough that it was running on its own steam.

But on twitter, economic historian Joe Francis offered a slightly different narrative. Although he agrees that a change to overseas trade was the prime mover, he suggests that the trade itself was too small as a proportion of the economy to account for much of London’s growth. I disagree, for various reasons that I won’t go into now, but Joe brought to my attention various changes on the monetary side. Inspired by the work of Nuno Palma, he suspects that it was not the trade per se, but the fact of an export surplus that was doing the heavy lifting, by increasing the country’s money supply.

An increased money supply should have facilitated England’s internal trades, reducing their costs, and allowing for greater regional specialisation. Joe essentially thinks that I’ve got the mechanism slightly back to front: instead of London’s growing demands having reshaped the countryside, he contends that the specialisation of the entire country is what allowed for the better allocation of economic resources and workers to where they were most productive — a process from which a large city like London quite naturally then emerged.

I have some doubts about whether this process could really have been led from the countryside. The regional specialisation that we see in agriculture, for example, only really starts to become obvious from the 1600s onwards, by which stage London’s population had already begun to balloon from a puny 50,000 in 1550, to 200,000 and rising. I also haven’t found much evidence of other internal trade costs falling. Internal transportation — by packhorse, river, or down the coast — doesn’t seem to have become all that more efficient. Roads and waggon services don’t show much sign of improvement until the eighteenth century, and not many rivers were made more navigable before the mid-seventeenth century either. This is not to say that England’s internal trade didn’t increase. It certainly did, as London sucked in food and fuel in ever larger quantities, and from farther and farther afield. But it still looks like this was led by London demand, rather than by falling costs elsewhere.

Besides, the influxes of bullion from abroad would have all been channelled through London first, along with most of the country’s trade. To the extent that monetisation made a difference to the costs of trade then, this would have made a difference first in the city, before emanating out to its main suppliers, and then outwards. I thus see the Palma narrative as potentially complementary to my own.

September 20, 2021

QotD: English jingoism

In England all the boasting and flag-wagging, the “Rule Britannia” stuff, is done by small minorities. The patriotism of the common people is not vocal or even conscious. They do not retain among their historical memories the name of a single military victory. English literature, like other literatures, is full of battle-poems, but it is worth noticing that the ones that have won for themselves a kind of popularity are always a tale of disasters and retreats. There is no popular poem about Trafalgar or Waterloo, for instance. Sir John Moore’s army at Corunna, fighting a desperate rear-guard action before escaping overseas (just like Dunkirk!) has more appeal than a brilliant victory. The most stirring battle-poem in English is about a brigade of cavalry which charged in the wrong direction. And of the last war, the four names which have really engraved themselves on the popular memory are Mons, Ypres, Gallipoli and Passchendaele, every time a disaster. The names of the great battles that finally broke the German armies are simply unknown to the general public.

The reason why the English anti-militarism disgusts foreign observers is that it ignores the existence of the British Empire. It looks like sheer hypocrisy. After all, the English have absorbed a quarter of the earth and held on to it by means of a huge navy. How dare they then turn round and say that war is wicked?

It is quite true that the English are hypocritical about their Empire. In the working class this hypocrisy takes the form of not knowing that the Empire exists. But their dislike of standing armies is a perfectly sound instinct. A navy employs comparatively few people, and it is an external weapon which cannot affect home politics directly. Military dictatorships exist everywhere, but there is no such thing as a naval dictatorship. What English people of nearly all classes loathe from the bottom of their hearts is the swaggering officer type, the jingle of spurs and the crash of boots. Decades before Hitler was ever heard of, the word “Prussian” had much the same significance in England as “Nazi” has to-day. So deep does this feeling go that for a hundred years past the officers of the British Army, in peace-time, have always worn civilian clothes when off duty.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.