Insider Food

Published Dec 4, 2019Stilton cheese takes its name from the village of Stilton, in the east of England. The earliest reports of cheese made and sold here date to the 17th century. In 1724, English writer Daniel Defoe referred to the town being “famous for cheese”, calling the product the “English Parmesan”. Today, Stilton can only be made in six dairies, which are spread across three counties in England: Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, and Derbyshire. We visited Colston Bassett Dairy in Nottinghamshire to learn more about the cheese is made.

For more, visit:

https://www.colstonbassettdairy.co.uk/——————————————————

(more…)

April 7, 2024

How Traditional English Stilton Cheese Is Made At A 100-Year-Old Dairy | Regional Eats

February 21, 2024

QotD: Mid-century London

Two of the novels were by, respectively, Nigel Balchin and R. C. Hutchinson, writers well regarded in their time but now mostly forgotten, while the third was by Ivy Compton-Burnett, who still has her admirers. They were quite different authors, but each had an unmistakable quality of unreconstructed English national identity, such as no writer about London — where two of the novels are set — or anywhere else in the country could now convey.

It is not that foreigners could not be found in 1949 London, which was then still a port city of some importance. In Hutchinson’s book, Elephant and Castle, set largely in the East End, one of the main characters is half-Italian, and foreigners of various nationalities have walk-on parts. But they in no way affect the strongly English character of the city. Today’s London, by contrast, seems more like a dormitory for an ever-fluctuating population than a home; even much of its physical fabric has been completely denationalized by modernist architecture of a sub-Dubai quality. It is not a melting pot, for little is left to melt into; a better culinary metaphor might be a stir-fry, the ingredients remaining unblended — though, with luck, compatible.

Theodore Dalrymple, “What Seventy Years Have Wrought”, New English Review, 2019-10-26.

February 1, 2024

QotD: English hypocrisy, spoken

Sir Guthrie is a hybrid, a scientist-turned-apparatchik. “I’m sorry to be a nuisance,” he says, in that suave, hypocritical English way, which is at once admirable and disagreeable. This manner of speaking, of never saying quite what you mean, was illustrated in a French book of the time, La Vie anglaise, which tried to explain English manners to the French. When an Englishman says, “We must meet again,” the author explains, he means: “I hope never to see you again”; and when he says, “I know a little about”, he means: “I am an expert in”, or possibly even “the world-expert in”.

Alas, this indirect way of speaking, always tinged with irony and humour, has almost disappeared in favour of a cruder and less amusing manner of communicating. Literal-mindedness has replaced subtle codification, and with it, a people who were once subtle, if sometimes perfidious, have become crass and often aggressive. Irony, which the whole population once both understood and employed, and was so strong an aspect of the national character, has now disappeared, replaced by a disposition to querulousness and indignation.

Theodore Dalrymple, “What Seventy Years Have Wrought”, New English Review, 2019-10-26.

December 29, 2023

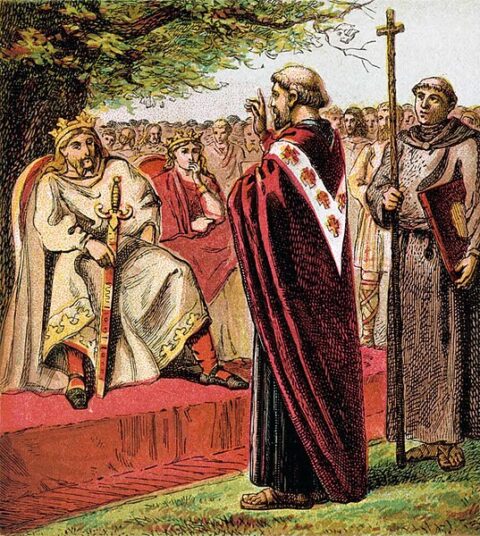

The Christianization of England

Ed West‘s Christmas Day post recounted the beginnings of organized Christianity in England, thanks to the efforts of Roman missionaries sent by Pope Gregory I:

“Saint Augustine and the Saxons”

Illustration by Joseph Martin Kronheim from Pictures of English History, 1868 via Wikimedia Commons.

The story begins in sixth century Rome, once a city of a million people but now shrunk to a desolate town of a few thousand, no longer the capital of a great empire of even enjoying basic plumbing — a few decades earlier its aqueducts had been destroyed in the recent wars between the Goths and Byzantines, a final blow to the great city of antiquity. Under Pope Gregory I, the Church had effectively taken over what was left of the town, establishing it as the western headquarters of Christianity.

Rome was just one of five major Christian centres. Constantinople, the capital of the surviving eastern Roman Empire, was by this point far larger, and also claimed leadership of the Christian world — eventually the two would split in the Great Schism, but this was many centuries away. The other three great Christian centres — Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch — would soon fall to Islam, a turn of events that would strengthen Rome’s spiritual position. And it was this Roman version of Christianity which came to shape the Anglo-Saxon world.

Gregory was a great reformer who is viewed by some historians as a sort of bridge between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the founder of a new and reborn Rome, now a spiritual rather than a military empire. He is also the subject of the one great stories of early English history.

One day during the 570s, several years before he became pontiff, Gregory was walking around the marketplace when he spotted a pair of blond-haired pagan slave boys for sale. Thinking it tragic that such innocent-looking children should be ignorant of the Lord, he asked a trader where they came from, and was told they were “Anglii”, Angles. Gregory, who was fond of a pun, replied “Non Angli, sed Angeli” (not Angles, but angels), a bit of wordplay that still works fourteen centuries later. Not content with this, he asked what region they came from and was told “Deira” (today’s Yorkshire). “No,” he said, warming to the theme and presumably laughing to himself, “de ira” — they are blessed.

Impressed with his own punning, Gregory decided that the Angles and Saxons should be shown the true way. A further embellishment has the Pope punning on the name of the king of Deira, Elle, by saying he’d sing “hallelujah” if they were converted, but it seems dubious; in fact, the Anglo-Saxons were very fond of wordplay, which features a great deal in their surviving literature and without spoiling the story, we probably need to be slightly sceptical about whether Gregory actually said any of this.

The Pope ordered an abbot called Augustine to go to Kent to convert the heathens. We can only imagine how Augustine, having enjoyed a relatively nice life at a Benedictine monastery in Rome, must have felt about his new posting to some cold, faraway island, and he initially gave up halfway through his trip, leaving his entourage in southern Gaul while he went back to Rome to beg Gregory to call the thing off.

Yet he continued, and the island must have seemed like an unimaginably grim posting for the priest. Still, in the misery-ridden squalor that was sixth-century Britain, Kent was perhaps as good as it gets, in large part due to its links to the continent.

Gaul had been overrun by the Franks in the fifth century, but had essentially maintained Roman institutions and culture; the Frankish king Clovis had converted to Catholicism a century before, following relentless pressure from his wife, and then as now people in Britain tended to ape the fashions of those across the water.

The barbarians of Britain were grouped into tribes led by chieftains, the word for their warlords, cyning, eventually evolving into its modern usage of “king”. There were initially at least twelve small kingdoms, and various smaller tribal groupings, although by Augustine’s time a series of hostile takeovers had reduced this to eight — Kent, Sussex, Essex, and Wessex (the West Country and Thames Valley), East Anglia, Mercia (the Midlands), Bernicia (the far North), and Deira (Yorkshire).

In 597, when the Italian delegation finally finished their long trip, Kent was ruled by King Ethelbert, supposedly a great-grandson of the semi-mythical Hengest. The king of Kent was married to a strong-willed Frankish princess called Bertha, and luckily for Augustine, Bertha was a Christian. She had only agreed to marry Ethelbert on condition that she was allowed to practise her religion, and to keep her own personal bishop.

Bertha persuaded her husband to talk to the missionary, but the king was perhaps paranoid that the Italian would try to bamboozle him with witchcraft, only agreeing to meet him under an oak tree, which to the early English had magical properties that could overpower the foreigner’s sorcery. (Oak trees had a strong association with religion and mysticism throughout Europe, being seen as the king of the trees and associated with Woden, Zeus, Jupiter, and all the other alpha male gods.)

Eventually, and persuaded by his wife, Ethelbert allowed Augustine to baptise 10,000 Kentish men on Christmas Day, 597, according to the chronicles. This is probably a wild exaggeration; 10,000 is often used as a figure in medieval history, and usually just means “quite a lot of people”.

December 25, 2023

QotD: Washington Irving and American Christmas traditions

… the man who did more than any other US citizen to shape the American Christmas. I am not sure how many people read Washington Irving these days, but I would wager that a large proportion of those who don’t are still vaguely familiar with his creation Rip van Winkle — and, if only through his memorialization in institutions like the New York Knicks, his fictitious Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker.

An even larger number may be unaware of how much they’re honoring Mr Irving in their Christmas jubilations. He it was who, in the 1812 edition of his History of New York, threw in a whimsical vignette in which St Nicholas flies over the treetops in a wagon while puffing on his pipe. No reindeer, but all the other elements of the American Santa are there.

Washington Irving loved the great village revelries of the old English Christmas, which the Puritans had left far behind them when they landed at Plimouth Plantation. The parlor games and community feasting and the notion of the Saviour’s birth as a cause of merriment all appealed to him. In his famous and bestselling Sketch Book of 1819-1820 five chapters are devoted to lovingly detailed scenes from an English family Christmas as observed by a young visitor, and they proved so popular that half-a-century later (by which time almost all the elements had been imported into American life) they were published as a stand-alone book.

Mark Steyn, “Dangling Hares and Rosy-Cheeked Schoolboys”, SteynOnline, 2021-12-20.

November 30, 2023

QotD: “Information velocity” in the English Civil War

Information velocity had increased exponentially by the 1630s, such that the English Civil War was, in a fundamental way, a propaganda war, an intellectual war.

Some of the battles of the Wars of the Roses were bigger than some of the Civil War’s battles – an estimated 50,000 men fought at Towton, in 1461 – but the Civil War was inconceivably harder and nastier than the Wars of the Roses, because the Civil War was an ideological war. The Wars of the Roses could’ve ended, at least theoretically, at any time – get the king and five dukes in a room, hammer out a compromise, and simply order everyone in each lord’s affinity to lay down his weapons. The Civil War could only end when everyone, in every army, was persuaded to lay down his arms.

Thus the winners had to negotiate with the people, directly. The Putney Debates didn’t involve everyone in the realm, but they were representative, truly representative, of everyone who mattered. Though no one explicitly made an appeal to competence alone, it was – and is, and must be – fundamental to representative government. Guys like Gerrard Winstanley had some interesting ideas, but they were fundamentally impractical, and Winstanley was not popularly viewed as a competent leader. Oliver Cromwell, on the other hand, was competence personified – the Protectorate became Cromwell’s military dictatorship largely because the People, as literally represented by the New Model Army, wanted it so … and, thanks to much faster information velocity, could make their wishes known.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

November 29, 2023

Alfred the Great

Ed West‘s new book is about the only English king to be known as “the Great”:

There are no portraits of King Alfred from his time period, so representations like this 1905 stained glass window in Bristol Cathedral are all we have to visually represent him.

Photo by Charles Eamer Kempe via Wikimedia Commons.

History was once the story of heroes, and there is no greater figure in England’s history than the man who saved, and helped create, the nation itself. As I’ve written before, Alfred the Great is more than just a historical figure to me. I have an almost Victorian reverence for his memory.

Alfred is the subject of my short book Saxons versus Vikings, which was published in the US in 2017 as the first part of a young adult history of medieval England. The UK edition is published today, available on Amazon or through the publishers. (use the code SV20 on the publisher’s site, valid until 30 November, which gives 20% off). It’s very much a beginner’s introduction, aimed at conveying the message that history is just one long black comedy.

The book charts the story of Alfred and his equally impressive grandson Athelstan, who went on to unify England in 927. In the centuries that followed Athelstan may have been considered the greater king, something we can sort of guess at by the fact that Ethelred the Unready named his first son Athelstan, and only his eighth Alfred, and royal naming patterns tend to reflect the prestige of previous monarchs.

Yet while Athelstan’s star faded in the medieval period, Alfred’s rose, and so by the fifteenth century the feeble-minded Henry VI was trying to have him made a saint. This didn’t happen, but Alfred is today the only English king to be styled “the Great”, and it was a word attached to him from quite an early stage. Even in the twelfth century the gossipy chronicler Matthew Paris is using the epithet, and says it’s in common use.

However, much of what is recorded of him only became known in Tudor times, partly by accident. Henry VIII’s break from Rome was to have a huge influence on our understanding of history, chiefly because so many of England’s records were stored in monasteries.

Before the development of universities, these had been the main intellectual centres in Christendom, indeed from where universities would grow. Now, along with relics, huge amounts of them would be lost, destroyed, sold … or preserved.

It was lucky that Matthew Parker, the sixteenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury with a keen interest in history, had a particularly keen interest in Alfred. It was Parker who published Asser’s Life of Alfred in 1574, having found the manuscript after the dissolution of the monasteries, a book that found itself in the Ashburnham collection amassed by Sir Robert Cotton in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Sadly, the original Life was burned in a famous fire at Ashburnham House in Westminster on October 23, 1731. Boys from nearby Westminster School had gone into the blaze alongside the owner and his son to rescue manuscripts, but much was lost, among them the only surviving manuscript of the Life of Alfred, as well as that of Beowulf. In fact the majority of recorded Anglo-Saxon history had gone up in smoke in minutes.

A copy of Beowulf had also been made, although the poem only became widely known in the nineteenth century after being translated into modern English. The fire also destroyed the oldest copy of the Burghal Hidage, a unique document listing towns of Saxon England and provisions for defence made during the reign of Alfred’s son Edward the Elder. An eighth-century illuminated gospel book from Northumbria was also lost.

So it is lucky that Parker had had The Life of Alfred printed, even if he had made alterations in his copy that to historians are infuriating because they cannot be sure if they are authentic. He probably added the story about the cakes, for instance, although this had come from a different Anglo-Saxon source.

We also know that Archbishop Parker was a bit confused, or possibly just lying; he claimed Alfred had founded his old university, Oxford, which was clearly untrue, and he was probably trying to make his alma mater sound grander than Cambridge. Oxford graduates down the years have been known to do this on one or two occasions.

November 22, 2023

“[T]he Tudors were indeed pretty awful, and that the writers who lived under this dynasty did serve as propagandists”

I quite like a lot of what Ed West covers at Wrong Side of History, but I’m not convinced by his summary of the character of King Richard III nor do I believe him guilty of murdering his nephews, the famed “Princes in the Tower”:

As Robert Tombs put it in The English and their History, no other country but England turned its national history into a popular drama before the age of cinema. This was largely thanks to William Shakespeare’s series of plays, eight histories charting the country’s dynastic conflict from 1399 to 1485, starting with the overthrow of the paranoid Richard II and climaxing with the War of the Roses.

This second part of the Henriad covered a 30-year period with an absurdly high body count – three kings died violently, seven royal princes were killed in battle, and five more executed or murdered; 31 peers or their heirs also fell in the field, and 20 others were put to death.

And in this epic national story, the role of the greatest villain is reserved for the last of the Plantagenets, Richard III, the hunchbacked child-killer whose defeat at Bosworth in 1485 ended the conflict (sort of).

Yet despite this, no monarch in English history retains such a fan base, a devoted band of followers who continue to proclaim his innocence, despite all the evidence to the contrary — the Ricardians.

One of the most furious responses I ever provoked as a writer was a piece I wrote for the Catholic Herald calling Richard III fans “medieval 9/11 truthers”. This led to a couple of blogposts and several emails, and even an angry phone call from a historian who said I had maligned the monarch.

This was in the lead up to Richard III’s reburial in Leicester Cathedral, two and a half years after the former king’s skeleton was found in a car park in the city, in part thanks to the work of historian Philippa Langley. It was a huge event for Ricardians, many of whom managed to get seats in the service, broadcast on Channel 4.

Apparently Philippa Langly’s latest project — which is what I assume raised Ed’s ire again — is a new book and Channel 4 documentary in which she makes the case for the Princes’ survival after Richard’s reign although (not having read the book) I’d be wary of accepting that they each attempted to re-take the throne in the guises of Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck.

The Ricardian movement dates back to Sir George Buck’s revisionist The History of King Richard the Third, written in the early 17th century. Buck had been an envoy for Elizabeth I but did not publish his work in his lifetime, the book only seeing the light of day a few decades later.

Certainly, Richard had his fans. Jane Austen wrote in her The History of England that “The Character of this Prince has been in general very severely treated by Historians, but as he was a York, I am rather inclined to suppose him a very respectable Man”.

But the movement really began in the early 20th century with the Fellowship of the White Boar, named after the king’s emblem, now the Richard III Society.

It received a huge boost with Josephine Tey’s bestselling 1951 novel The Daughter of Time in which a modern detective manages to prove Richard innocence. Paul Murray Kendall’s Richard the Third, published four years later, was probably the most influential non-fiction account to take a sympathetic view, although there are numerous others.

One reason for Richard’s bizarre popularity is that the Tudors were indeed pretty awful, and that the writers who lived under this dynasty did serve as propagandists.

Writers tend to serve the interests of the ruling class. In the years following Richard III’s death John Rous said of the previous king that “Richard spent two whole years in his mother’s womb and came out with a full set of teeth and hair streaming to his shoulders”. Rous called him “monster and tyrant, born under a hostile star and perishing like Antichrist”.

However, when Richard was alive the same John Rous was writing glowing stuff about him, reporting that “at Woodstock … Richard graciously eased the sore hearts of the inhabitants” by giving back common lands that had been taken by his brother and the king, when offered money, said he would rather have their hearts.

Certainly, there was propaganda. As well as the death of Clarence, William Shakespeare — under the patronage of Henry Tudor’s granddaughter — also implicated Richard in the killing the Duke of Somerset at St. Albans, when he was a two-year-old. The playwright has him telling his father: “Heart, be wrathful still: Priests pray for enemies, but princes kill”. So it’s understandable why historians might not believe everything the Bard wrote about him.

I must admit to a bias here, as I wrote back in 2011:

In the interests of full disclosure, I should point out that I portrayed the Earl of Northumberland in the 1983 re-enactment of the coronation of Richard III (at the Cathedral Church of St. James in Toronto) on local TV, and I portrayed the Earl of Lincoln in the (non-televised) version on the actual anniversary date. You could say I’m biased in favour of the revisionist view of the character of good King Richard.

November 20, 2023

A Tour of the Excavations at Vindolanda

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 4 Aug 2023This spring, Dr. Andrew Birley gave me a tour of the ongoing excavations at Vindolanda, a Roman fort near Hadrian’s Wall.

Chapters:

0:00 Welcome to Vindolanda

4:41 The wooden underworld

7:13 Layers of history

9:03 Becoming part of the story

November 8, 2023

Sampling the alternate history field

Jane Psmith confesses a weakness for a certain kind of speculative fiction and recommends some works in that field. The three here are also among my favourites, so I can comfortably agree with the choices:

As I’ve written before, I am an absolute sucker for alternate history. Unfortunately, though, most of it is not very good, even by the standards of genre fiction’s transparent prose. Its attraction is really the idea, with all its surprising facets, and means the best examples are typically the ones where the idea is so good — the unexpected ramifications so startling at the moment but so obvious in retrospect — that you can forgive the cardboard characters and lackluster prose.

But, what the heck, I’m feeling self-indulgent, so here are some of my favorites.

- Island in the Sea of Time et seq., by S.M. Stirling: This is my very favorite. The premise is quite simple: the island of Nantucket is inexplicably sent back in time to 1250 BC. Luckily, a Coast Guard sailing ship happens to be visiting, so they’re able to sail to Britain and trade for grain to survive the winter while they bootstrap industrial civilization on the thinly-inhabited coast of North America. Of course, it’s not that simple: the inhabitants of the Bronze Age have obvious and remarkably plausible reactions to the sudden appearance of strangers with superior technology, a renegade sailor steals one of the Nantucketers’ ships and sets off to carve his own empire from the past, and the Americans are thrust into Bronze Age geopolitics as they attempt to thwart him. The “good guys” are frankly pretty boring, in a late 90s multicultural neoliberal kind of way — the captain of the Coast Guard ship is a black lesbian and you can practically see Stirling clapping himself on the back for Representation — but the villainous Coast Guardsmen and (especially) the natives of 1250 BC get a far more complex and interesting portrayal.1 Two of them are particularly well-drawn: a fictional trader of the thinly attested Iberian city-state of Tartessos, and an Achaean nobleman named Odikweos, both of whom are thoroughly understandable and sympathetic while remaining distinctly unmodern. The Nantucketers, with their technological innovations and American values, provide plenty of contrast, but Stirling is really at his best in using them to highlight the alien past.

- Lest Darkness Fall, by L. Sprague de Camp: An absolute classic of the genre. I may not love what de Camp did with Conan, but the man could write! One of the great things about old books (this one is from 1939) is that they don’t waste time on technobabble to justify the silly parts: about two pages into the story, American archaeologist Martin Padway is struck by lightning while visiting Rome and transported back in time to 535 AD. How? Shut up, that’s how, and instead pay attention as Padway introduces distilled liquor, double-entry bookkeeping, yellow journalism, and the telegraph before taking advantage of his encyclopedic knowledge of Procopius’s De Bello Gothico to stabilize and defend the Italo-Gothic kingdom, wrest Belisarius’s loyalty away from Justinian, and entirely forestall the Dark Ages. If this sounds an awful lot like the imaginary book I described in my review of The Knowledge: yes. The combination of high agency history rerouting and total worldview disconnect — there’s a very funny barfight about Christology early on, and later some severe culture clash that interferes with a royal marriage — is charming. Also, this was the book that inspired Harry Turtledove not only to become an alt-history writer but to get a Ph.D. in Byzantine history.

[…]

- Ruled Britannia, by Harry Turtledove: Turtledove is by far the most famous and successful alternate history author out there, with lots of short pieces and novels ranging from “Byzantine intrigue in a world where Islam never existed” (Agent of Byzantium) to “time-travelling neo-Nazis bring AK-47s to the Confederacy” (The Guns of the South), but this is the only one of his books I’ve ever been tempted to re-read. The jumping-off point, “the Spanish Armada succeeded”, is fairly common for the genre2 — the pretty good Times Without Number and the lousy Pavane (hey, did you know the Church hates and fears technology?!) both start from there — but Turtledove fasts forward only a decade to show us William Shakespeare at the fulcrum of history. A loyalist faction (starring real life Elizabethan intriguers like Nicholas Skeres) wants him to write a play about Boudicca to inflame the population to free Queen Elizabeth from her imprisonment in the Tower of London, while the Spanish authorities (represented, hilariously, by playwright manqué Lope de Vega) want him to write one glorifying the late Philip II and the conquest of England. Turtledove does a surprisingly good job inventing new Shakespeare plays from snippets of real ones and from John Fletcher’s 1613 Bonduca, but of course I’m most taken by his rendition of the Tudor world. Maybe I should check out some of his straight historical fiction …

1. Well, except for the peaceful matriarchal Marija Gimbutas-y “Earth People” being displaced from Britain by the invading Proto-Celts; they’re also “good guys” and therefore, sadly, boring.

2. Not as common as “the Nazis won”, obviously.

I agree with Jane about Island in the Sea of Time, but my son and daughter-in-law strongly preferred the other series Stirling wrote from the same start point: what happened to the world left behind when Nantucket Island got scooped out of our timeline and dumped back into the pre-collapse Bronze Age. Whereas ISOT has minimal supernatural elements to the story, the “Emberverse” series beginning with Dies the Fire went on for many, many more books and had much more witchy woo-woo stuff front-and-centre rather than marginal and de-emphasized.

While I quite enjoyed Ruled Britannia, it was the first Turtledove series I encountered that I’ve gone back to re-read: The Lost Legion … well, the first four books, anyway. He wrote several more books in that same world, but having wrapped up the storyline for the Legion’s main characters, I didn’t find the others as interesting.

November 5, 2023

Guy Fawkes and The Gunpowder Plot 1605

The History Chap

Published 4 Nov 2022The story behind Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, the audacious plan to kill the king of England. It is also the complicated story behind our annual Bonfire Night celebrations.

In 1605 a group of dissident Catholics came within a whisker of one of the greatest assassination coups in history — blowing up the King of England, and his government as he attended parliament in London. 36 barrels of gunpowder (approximately 1 tonne of explosives) had been placed directly under where he would open parliament. Experts estimate that no one within 300 feet would have survived.

Had it succeeded it would have rivalled 9/11 in its audacity and would have changed English (& arguably world) history forever. But who were the plotters, what were they trying to achieve and how close did they really come to success? Were they freedom fighters or 17th century terrorists? And why is only one conspirator, Guy Fawkes, remembered when he wasn’t even the brains behind the operation?

After years of persecution by England’s Protestants, a small group of Catholic nobles under Robert Catesby (aka Robin Catesby) decided to take matters into their own hands and blow up the king (King James I of England / James VI of Scotland) whilst he attended parliament in London.

Guy Fawkes (aka Guido Fawkes) smuggled 36 barrels of gunpowder into a cellar directly beneath the hall where parliament would meet in the Palace of Westminster. In the early hours of 5th November 1605, he was arrested by guards who had been tipped off about the gunpowder plot. After three days of torture in the Tower of London, Guy Fawkes finally broke and named his fellow conspirators.

The conspirators, under Robert Catesby, had fled London for the English midlands where they hoped to abduct the king’s daughter and organise a catholic rising. Both failed to materialise and Catesby’s small band were surrounded by a government militia at Holbeach House, just outside Kingswinford in Staffordshire. A brief shoot-out resulted in the death of some of the Catholic rebels (including their leader, Catesby) and the arrest of the others.

The surviving gunpowder plotters (including Guy Fawkes) were executed in London at the end of January 1606, by the grisly execution reserved for traitors — Hanged, drawn and quartered (quite literally a “living death”).

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was a complete failure but the event is still celebrated on the 5th November every year on Bonfire Night.

(more…)

October 28, 2023

QotD: Deposing King Charles I

It’s 1642, and once again the English are contemplating deposing a king for incompetence. Alas, the Reformation forces the rebels to confront the issue the deposers of Edward II and Richard II could duck: Divine sanction. The Lords Appellant could very strongly imply that Richard II had lost “the mandate of heaven” (to import an exoteric term for clarity), but they didn’t have to say it – indeed, culturally they couldn’t say it. The Parliamentarians had the opposite problem – not only could they say it, they had to, since the linchpin of Charles I’s incompetence was, in their eyes, his cack-handed efforts to “reform” religious practice in his kingdoms.

But on the other hand, if they win the ensuing civil war, that must mean that God’s anointed is … Oliver Cromwell, which is a notion none of them, least of all Oliver Cromwell, was prepared to accept. Moreover, that would make the civil war an explicitly religious war, and as the endemic violence of the last century had so clearly shown, there’s simply no way to win a religious war (recall that the ructions leading up to the English Civil War overlapped with the last, nastiest phase of the Thirty Years’ War, and that everyone had a gripe against Charles for getting involved, or not, in the fight for the One True Faith on the Continent).

The solution the English rebels came up with, you’ll recall, was to execute Charles I for treason. Against the country he was king of.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

October 24, 2023

The English language, who did what to it and when

The latest book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf is John McWhorter’s Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English. I’m afraid I often find myself feeling cut adrift in discussions of the evolution of languages, as if I’m floating out of control in a maelstrom of what was, what is, and what might be, linguistically speaking. It’s an uncomfortable feeling and in retrospect explains why I did so poorly in formal grammar classes. When Jane Psmith gets around to discussing actual historical dates, I find my metaphorical feet again:

Shakespeare wrote about five hundred years ago, and even aside from the frequency of meaningless “do” in normal sentences, it’s clear that our language has changed since his day. But it hasn’t changed that much. Much less, for example, than English changed between Beowulf (probably written in the 890s AD)1 and The Canterbury Tales (completed by 1400), another five hundred year gap. Just compare this:

Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.2

to this:

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour…3That’s a huge change! That’s way more than some extraneous verbs, the loss of a second person singular pronoun (thou knowest what I’m talking about), or a shift in some words’ definition.4 That’s practically unrecognizable! Why did English change so much between Beowulf and Chaucer, and so little between Shakespeare and me?

There’s a two part answer to this, and I’ll get to the real one in a minute (the changes between Old English and Middle English really are very interesting), but actually I must first confess that it was a trick question, because my dates are way off: even if people wrote lovely, fancy, highly-inflected Old English in the late 9th century, there’s no real reason to think that’s how they spoke.

On one level we know this must be true: after all, there were four dialects of Old English (Northumbrian, Mercian, Kentish, and West Saxon) and almost all our written sources are in West Saxon, even the ones from regions where that can’t have been the lingua franca.5 But it goes well beyond that: in societies where literacy is not widespread, written language tends to be highly conservative, formal, and ritualized. Take, for example, the pre-Reformation West, where all educated people used Latin for elite pursuits like philosophical disputatio or composing treatises on political theory but spoke French or Italian or German or English in their daily lives. It wasn’t quite Cicero’s Latin (though really whose is), but it was intentionally constructed so that it could have been intelligible to a Roman. Similarly, until quite recently Sanskrit was the written language of India even though it hadn’t been spoken for centuries. This happens in more modern and broadly literate societies as well: before the 1976 linguistic reforms, Greeks were deeply divided over “the language question” of whether to use the vernacular (dimotiki) or the elevated literary language (Katharevousa).6 And modern Arabic-speaking countries have an especially dramatic case of this: the written language is kept as close to the language of the Quran as possible, but the spoken language has diverged to the point that Moroccan Arabic and Saudi Arabic are mutually unintelligible.

Linguists call this phenomenon “diglossia”. It can seem counter-intuitive to English speakers, because we’ve had an unusually long tradition of literature in the vernacular, but even for those of us who use only “standard” English there are still notable differences between the way we speak and the way we write: McWhorter points out, for example, that if all you had was the corpus of Time magazine, you would never know people say “whole nother”. Obviously the situation is far more pronounced for people who speak non-standard dialects, whether AAVE or Hawaiian Pidgin (actually a creole) or Cajun English. (Even a hundred years ago, the English-speaking world had many more local dialects than it does today, so the experience of diglossia would have been far more widespread.)7

Anyway, McWhorter suggests that Old English seems to have changed very little because all we have is the writing, and the way you wrote wasn’t supposed to change. That’s why it’s so hard to date Beowulf from linguistic features: the written language of 600 is very similar to the written language of 1000! But despite all those centuries that the written language remained the perfectly normal Germanic language the Anglo-Saxons had brought to Britain, the spoken language was changing behind the scenes. As an increasing number of wealhs adopted it (because we now have the aDNA proof that the Anglo-Saxons didn’t displace the Celts), English gradually accumulated all sorts of Celtic-style “do” and “-ing” … which, obviously, no one would bother writing down, any more than the New York Times would publish an article written the way a TikTok rapper talks.

And then the Normans showed up.

The Norman Conquest had remarkably little impact on the grammar of modern English (though it brought a great deal of new vocabulary),8 but the replacement of the Anglo-Saxon ruling class more or less destroyed English literary culture. All of a sudden anything important enough to be written down in the first place was put into Latin or French, and by the time people began writing in English again two centuries later nothing remained of the traditional education in the conservative “high” Old English register. There was no one left who could teach you to write like the Beowulf poet; the only way to write English was “as she is spoke“, which was Chaucer’s Middle English.

So that’s one reason we don’t see the Celtic influence, with all its “do” and “-ing”, until nearly a thousand years after the Anglo-Saxons encountered the Celts. But there are a whole lot of other differences between Old English and Middle English, too, which are harder to lay at the Celtic languages’ door, and for those we have to look to another set of Germanic-speaking newcomers to the British Isles: the Vikings.

Grammatically, English is by far the simplest of the Germanic languages. It’s the only Indo-European language in Europe where nouns don’t get a gender — la table vs. le banc, for instance — and unlike many other languages it has very few endings. It’s most obvious with verbs: in English everyone except he/she/it (who gets an S) has a perfectly bare verb to deal with. None of this amō, amās, amat rigamarole: I, you, we, youse guys, and they all just “love”. (In the past, even he/she/it loses all distinction and we simply “loved”.) In many languages, too, you indicate a word’s role in the sentence by changing its form, which linguists call case. Modern English really only does this with our possessive (the word‘s role) and our pronouns,9 (“I see him” vs. “he sees me”); we generally indicate grammatical function with word order and helpful little words like “to” and “for”. But anyone learning Latin, or German, or Russian — probably the languages with case markings most commonly studied by English-speakers — has to contend with a handful of grammatical cases. And then, of course, there’s Hungarian.

As I keep saying, Old English was once a bog-standard Germanic language: it had grammatical gender, inflected verbs, and five cases (the familiar nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative, plus an instrumental case), each indicated by suffixes. Now it has none. Then, too, in many European languages, and all the other Germanic ones, when I do something that concerns only me — typically verbs concerning moving and feeling — I do it to myself. When I think about the past, I remember myself. If I err in German, I mistake myself. When I am ashamed in Frisian, I shame me, and if I go somewhere in Dutch I move myself. English preserves this in a few archaic constructions (I pride myself on the fact that my children can behave themselves in public, though I now run the risk of having perjured myself by saying so …), but Old English used it all the time, as in Beseah he hine to anum his manna (“Besaw he himself to one of his men”).

Another notable loss is in our direction words: in modern English we talk about “here”, “there”, or “where”, but not so long ago we could also discuss someone coming hither (“to here”) or ask whence (“from where”) they had gone. Every other Germanic language still has its full complement of directional adverbs. And most have a useful impersonal pronoun, like the German or Swedish man: Hier spricht man Deutsch.10 We could translate that as “one speaks German here” if we’re feeling pretentious, or perhaps employ the parental “we” (as in “we don’t put our feet in our mouths”), but English mostly forces this role on poor overused “you” (as in “you can’t be too careful”) because, again, we’ve lost our Old English man.

In many languages — including, again, all the other Germanic languages — you use the verb “be” to form the past perfect for words having to do with state or movement: “I had heard you speak”, but “I was come downstairs”. (This is the bane of many a beginning French student who has to memorize whether each verb uses avoir or être in the passé composée.) Once again, Old English did this, Middle English was dropping it, and modern English does it not at all. And there’s more, but I am taken pity on you …

1. This is extremely contentious. The poem is known to us from only one manuscript, which was produced sometime near the turn of the tenth/eleventh century, and scholars disagree vehemently both about whether its composition was contemporary with the manuscript or much earlier and about whether it was passed down through oral tradition before being written. J.R.R. Tolkien (who also had a day job, in his case as a scholar of Old English — the Rohirrim are more or less the Anglo-Saxons) was a strong proponent of the 8th century view. Personally I don’t have a strong opinion; my rhetorical point here could be just as clearly made with an Old English document of unimpeachably eleventh century composition, but Beowulf is more fun.

2. Old English orthography is not always obvious to a modern reader, so you can find a nice video of this being read aloud here. It’s a little more recognizable out loud, but not very.

3. Here‘s the corresponding video for Middle English, which I think is actually harder to understand out loud.

4. Of course words shift their meanings all the time. I’m presently reading Mansfield Park and giggling every time Fanny gets “knocked up” by a long walk.

5. Curiously, modern English derives much more from Mercian and Northumbrian (collectively referred to as “Anglian”) than from the West Saxon dialect that was politically dominant in the Anglo-Saxon period. Meanwhile Scots (the Germanic language, not to be confused with the Celtic language of Scots Gaelic or whatever thing that kid wrote Wikipedia in) has its roots in the Northumbrian dialect.

6. This is a more interesting and complicated case, because when the Greeks were beginning to emerge from under the Ottoman yoke it seemed obvious that they needed their own language (do you even nationalism, bro?) but spoken Greek was full of borrowings from Italian and Latin and Turkish, as well as degenerate vocabulary like ψάρι for “fish” when the perfectly good ιχθύς was right there. Many educated Greeks wanted to return to the ancient language but recognized that it was impractical, so Katharevousa (lit. “purifying”, from the same Greek root as “Cathar”) was invented as a compromise between dimotiki and “proper” Ancient Greek. Among other things, it was once envisioned as a political tool to entice the newly independent country’s Orthodox neighbors, who used Greek for their liturgies, to sign on to the Megali Idea. It didn’t work.

The word ψάρι, by the way, derives from the Ancient Greek ὀψάριον, meaning any sort of little dish eaten with your bread but often containing fish; see Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens for more. Most of the places modern Greek uses different vocabulary than the ancient tongue have equally fascinating etymologies. I think my favorite is άλογο, which replaced ίππος as the word for horse. See here for more.

7. Diglossia is such a big deal in so many societies that I’ve always thought it would be fun to include in my favorite genre, fantasy fiction, but it would be hard to represent in English. Anyone who’s bounced off Dickon’s dialogue in The Secret Garden or Edgar’s West Country English in King Lear knows how difficult it is to understand most of the actually-existing nonstandard dialects; probably the only one that’s sufficiently familiar to enough readers would be AAVE — but that would produce a very specific impression, and probably not the one you want. So I think the best alternative would be to render the “low” dialect in Anglish, a constructed vocabulary that uses Germanic roots in place of English’s many borrowings from Latin and French. (“So I think the best other way would be to give over the ‘low’ street-talk in Anglish, a built wordhoard that uses Germanic roots in spot of English’s many borrowings …”) It turns out Poul Anderson did something similar, because of course he did.

8. My favorite is food, because of course it is: our words for kinds of meat all derive from the French name for the animal (beef is boeuf, pork is porc, mutton is mouton) while our words for the animal itself have a good Germanic roots: cow, pig, sheep. Why? Well, think about who was raising the animal and who was eating it …

9. And even this is endangered; how many people do you know, besides me, who say “whom” aloud?

10. Yes, this is where Heidegger gets das Man.

October 16, 2023

QotD: Differentials of “information velocity” in a feudal society

[News of the wider world travels very slowly from the Royal court to the outskirts, but] information velocity within the sticks […] is very high. Nobody cares much who this “Richard II” cat was, or knows anything about ol’ Whatzisface – Henry Something-or-other – who might’ve replaced him, but everyone knows when the local knight of the shire dies, and everything about his successor, because that matters. So, too, is information velocity high at court – the lords who backed Henry Bolingbroke over Richard II did so because Richard’s incompetence had their asses in a sling. They were the ones who had to depose a king for incompetence, without admitting, even for a second, that

a) competence is a criterion of legitimacy, and

b) someone other than the king is qualified to judge a king’s competence.Because admitting either, of course, opens the door to deposing the new guy on the same grounds, so unless you want civil war every time a king annoys one of his powerful magnates, you’d best find a way to square that circle …

… which they did, but not completely successfully, because within two generations they were back to deposing kings for incompetence. Turns out that’s a hard habit to break, especially when said kings are as incompetent as Henry VI always was, and Edward IV became. Only the fact that the eventual winner of the Wars of the Roses, Henry VII, was as competent as he was as ruthless kept the whole cycle from repeating.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

October 15, 2023

History Summarized: The Castles of Wales

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 23 Jun 2023Every castle tells a story, but when one small country has over 600 castles, the collective story they tell is something like “holy heck ouch, ow, oh god, why are there so many arrows, ouch, good lord ow” – And that’s Wales for you.

(more…)