N.S. Lyons went to Barad-dûr Ottawa earlier this month to speak at the 2025 Civitas Canada Conference, and posted his remarks on his Substack:

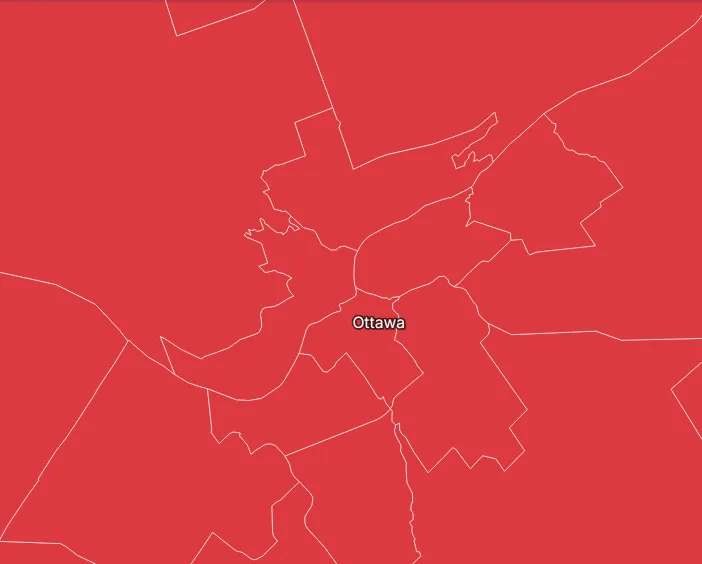

The 2022 Freedom Convoy induced a state of panic in the Canadian federal government, yet the elected representatives proved completely unwilling to even talk to anyone from the protests. The government clearly persuaded itself that this was an actual insurrection, and waited for the violence to break out … and there was no violence, other than that provided by the police and a few paid actors.

A screenshot from a YouTube video showing the protest in front of Parliament in Ottawa on 30 January, 2022.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Good evening ladies and gentlemen! It’s a pleasure to visit the North and get a glimpse behind the new Iron Curtain …

As it happens, the official theme of this conference is “Freedom and its Discontents: Liberal Democracy at a Crossroads”. That is a timely theme indeed. Because I think it isn’t too extreme to say that, all around the Western world today, democracy is under assault — even that it risks extinction. It risks extinction because the authorities that run our societies seem to find the practice, values, and very spirit of democracy to be increasingly intolerable.

In France, where the ruling government maintains power despite being the most widely hated in decades, the most popular candidate of the most popular political party has been barred from challenging that government in upcoming elections, on legal grounds that are openly political.

In Romania, when the “wrong” outsider candidate appeared poised to win an election, authorities simply canceled the election outright and then had him arrested, the unelected national security state inventing entirely unsupported excuses about foreign meddling to justify their coup d’état against the democratic process.

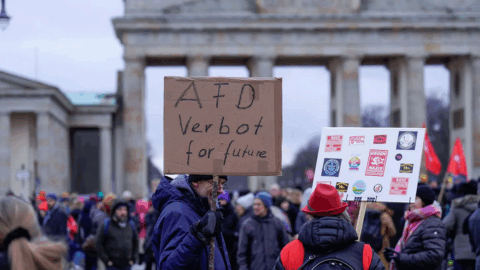

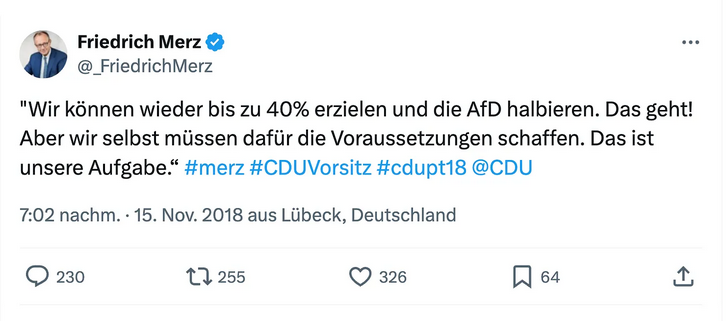

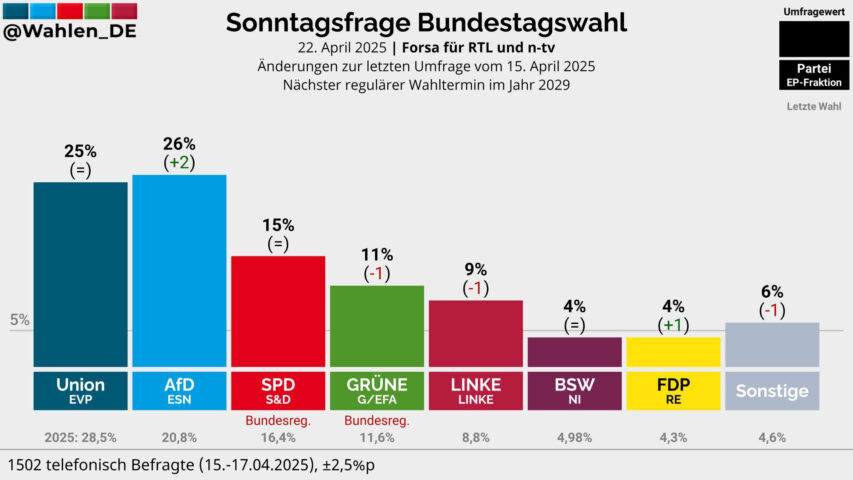

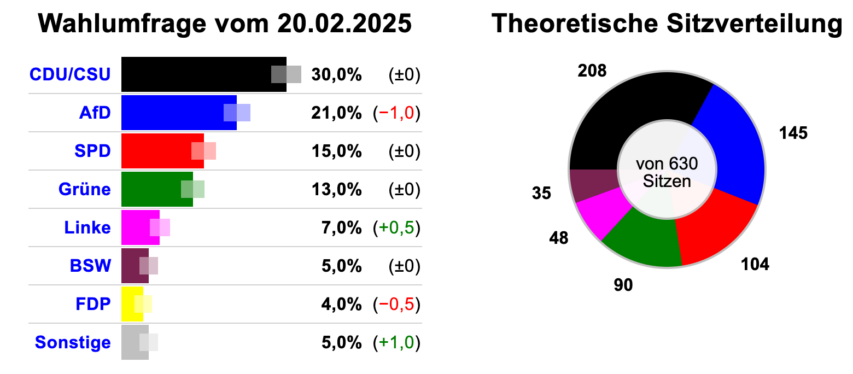

In Germany, the state has now begun the process of banning the country’s most popular party, supported by more than a quarter of the voting population, in order to avoid facing any real political opposition. “We did it in Romania, and we will obviously have to do it in Germany, if necessary”, is how a former European Commissioner confidently foreshadowed events on live television a few months ago.

One gets the sense that the honest view of our exasperated political elites is as captured in a Bloomberg News headline from last year which read: “2024 is a year of elections, and that’s a threat to democracy”.

In country after country, governments are moving to desperately tighten their grip over the people they rule, sharply curtailing freedom of speech and access to information, and using alleged threats to security and stability to justify granting themselves emergency powers, weaponizing the law, criminalizing dissent, and suppressing any meaningful political opposition.

In the United Kingdom, more than 12,000 people per year (that’s 33 per day on average) — are now arrested for speech- and literal thought-crimes, including silent prayer. UK jails now hold hundreds of political prisoners, more than anywhere else in Europe outside of Russia and Belarus. These are people persecuted for, essentially, voicing dissent over their government’s catastrophic policies. Recently, for instance, a British woman with no criminal history was jailed for more than two years for a single Facebook post criticizing the state’s willful failure to stop illegal migration.

In Brazil, a single Supreme Court judge, in alliance with the country’s leftist president, has effectively established a judicial dictatorship, locking up political rivals by decree, silencing the speech of opposition figures, and utilizing state leverage over the financial system to punish political enemies by banishing them from public economic life.

But of course Brazil’s authorities learned these tactics by observation. Observation of Canada, to be precise, where Justin Trudeau’s government first employed debanking — along with a little brute force — as a tool to crush peaceful protest of his draconian and disastrous pandemic lockdown policies.

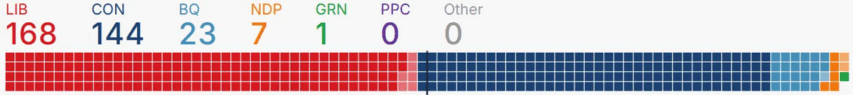

Today, the Canadian government’s weaponization of the legal system and public institutions, including state-funded media, to impose a quasi-totalitarian progressive ideological regime, censor and jail dissenters, and effectively transform Canada into a one-party state, has, I’m afraid, won your country a real measure of global infamy. Many Canadians here may not be aware of just how your government appears from the outside, but I’m afraid it’s not a good look at all. Unfortunately I must report that when many of us look at Canada what we see is a global leader in progressive authoritarianism, out-of-control migration, growing anarcho-tyranny, foreign subversion, and ideologically-induced economic stagnation.

But then, what we might realistically call the liberal-authoritarian model is, sadly, the new normal in the West, where many hyphenated liberal-democracies seem to have concluded that they must now begin to cast off the democratic half of that historical compact.

It may seem that this hardening of control is a response to the rise of so-called populism, which has swept the Western world. Certainly many authoritarian measures have been justified, without any sense of irony, as necessary to defend “our democracy” (so-called) against the dissatisfaction of the actual demos. And it’s true that fear of populism — which is really fear of genuine democracy — does seem to consistently provoke a spiral of ham-fisted reactions by our increasingly authoritarian states. But the reality is that populism is itself a reaction, an organic immune response to the particularly unresponsive and anti-democratic new form of governance that has visibly overtaken the West in recent decades.