… it occurs to me that movies aren’t the best example of the Current Year’s creative bankruptcy — music is. Somewhere below, I joked that Pink Floyd’s album The Wall was a modern attempt at a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk, a “total art work”. Wagner thought opera should be a complete aesthetic experience, that a great opera would have not just great music, but a great story in the libretto, great poetry in the lyrics, great painting in the set design, and so on, all of which would combine to something much greater than the sum of its already-excellent parts.

As I said, that’s awfully heavy for an album whose most famous song asks how can you have any pudding if you don’t eat your meat, but it’s nonetheless an accurate description of what Roger Waters was trying to do with the integrated concept album / movie / stage show. Whether or not he knew he was attempting a Gesamtkunstwerk in the full Wagnerian sense is immaterial, as is the question of whether or not he succeeded. Nor does it matter if The Wall is any good, musically or cinematically or lyrically.* The point is, he gave it one hell of a go … and nobody else has, even though these days it’d be far, far easier.

Consider what a band like Rush in their prime would’ve done with modern technology. I’m not a musician, but I’ve been told by people who are that you can make studio-quality stuff with free apps like Garage Band. Seriously, it’s fucking free. So is YouTube, and even high-quality digital cameras cost next to nothing these days, and even laptops have enough processor power to crank out big league video effects, with off-the-shelf software. I’m guessing (again, I’m no musician, let alone a filmmaker), but I’d wager some pretty good money you could make an actual, no-shit Gesamtkunstwerk — music, movie, the whole schmear — for under $100,000, easy. You think 2112-era Rush wouldn’t have killed it on YouTube?

I take a backseat to no man in my disdain for prog rock, but I have a hard time believing Neal Peart and the Dream Theater guys were the apex of rock’n’roll pretension. I realize I’ve just given the surviving members of Styx an idea, and we should all be thankful Kilroy Was Here was recorded in 1983, not 2013, because that yawning vortex of suck would’ve destroyed all life in the solar system, but I’m sure you see my point.** Why has nobody else tried this? Just to stick with a long-running Rotten Chestnuts theme, “Taylor Swift”, the grrl-power cultural phenomenon, is just begging for the Gesamtkunstwerk treatment. Apparently she’s trying real hard to be the June Carter Cash of the New Millennium™ these days, and hell, even I’d watch it.***

The fact that it hasn’t been attempted, I assert, is the proof that it can’t be done. The culture isn’t there, despite the tools being dirt cheap and pretty much idiot proof. Which says a LOT about the Current Year, none of it good.

* The obvious comment is that Roger Waters is no Richard Wagner, but that’s fatuous — even if you don’t like Wagner (I don’t, particularly), you have to acknowledge he’s about the closest thing to a universal artistic genius the human race has produced. It’s meaningless to say that Roger Waters isn’t in Wagner’s league, because pretty much nobody is in Wagner’s league. And philistine though I undoubtedly am, I’d much rather listen to The Wall than pretty much any opera — I enjoy the symphonic bits, but opera singing has always sounded like a pack of cats yodeling to me. I’m with the Emperor from Amadeus: “Too many notes.”

** If you have no idea what I’m talking about, then please, I’m begging you, do NOT go listen to “Mr. Roboto.” Whatever you do, don’t click that link …

… you clicked it, didn’t you? And now you’ll be randomly yelling “domo arigato, Mister Roboto!!” for days. You’ll probably get punched more than once for that. Buddy, I tried to warn you.

*** Anthropological interest only. I know I’m in the distinct minority on this one, but she never turned my crank, even in her “fresh-scrubbed Christian country girl” stage. Too sharp featured, and too obviously mercenary, even back then.

Severian, “More Scattered Thoughts”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-13.

May 4, 2023

QotD: Gesamtkunstwerk

May 2, 2023

QotD: The musical importance of the city of Córdoba

Which city is our best role model in creating a healthy and creative musical culture?

Is it New York or London? Paris or Tokyo? Los Angeles or Shanghai? Nashville or Vienna? Berlin or Rio de Janeiro?

That depends on what you’re looking for. Do you value innovation or tradition? Do you want insider acclaim or crossover success? Is your aim to maximize creativity or promote diversity? Are you seeking timeless artistry or quick money attracting a large audience?

Ah, I want all of these things. So I only have one choice — but I’m sure my city isn’t even on your list.

My ideal music city is Córdoba, Spain.

But I’m not talking about today. I’m referring to Córdoba around the year 1000 AD.

I will make a case that medieval Córdoba had more influence on global music than any other city in history. That’s probably not something you expected. But even if you disagree — and I already can hear some New Yorkers grumbling in the background — I think you will discover that the “Córdoba miracle,” as I call it, is an amazing role model for us.

It’s a case study in how communities foster the arts — and in a way that benefits everybody, not just the artists.

[…] a thousand years before New Orleans spurred the rise of jazz, and instigated the Africanization of American music, a similar thing happened in Córdoba, Spain. You could even call that city the prototype for all the decisive musical trends of our modern times.

“This was the chapter in Europe’s culture when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived side by side,” asserts Yale professor María Rosa Menocal, “and, despite their intractable differences and enduring hostilities, nourished a complex culture of tolerance.”

There’s even a word for this kind of cultural blossoming: Convivencia. It translates literally as “live together.” You don’t hear this term very often, but you should — because we need a dose of it now more than ever. And when scholars discuss and debate this notion of Convivencia, they focus their attention primarily on one city: Córdoba.

It represents the historical and cultural epicenter of living together as a norm and ideal.

Even today, we can see the mixture of cultures in Spain’s distinctive architecture, food, and music. These are both part of Europe, but also separate from it. It is our single best example of how the West can enter into fruitful cultural dialogue with the outsider — to the benefit of both.

Ted Gioia, “The Most Important City in the History of Music Isn’t What You Think It Is”, The Honest Broker, 2023-01-26.

April 26, 2023

QotD: The vanishing “entertainer” of yore

As I wrote somewhere in the comments below, we’ve done ourselves a real disservice, culturally, by all but abandoning the profession of “entertainer”. Lennon and McCartney could’ve been the mid 20th century equivalent of Gilbert and Sullivan, writing catchy tunes and performing fun shows, but they got artistic pretensions and we, the public, indulged them, so now everyone who gets in front of a camera — which, in the Social Media age, is pretty much everyone — thinks he has both the right and the duty to educate The Masses.

It was still possible — barely — to be an entertainer as late as the early 2000s. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson was one. Schwarzenegger’s dharma heir, he, along with guys like Jason Statham, made goofy shoot-em-up movies in which improbably muscled men killed a bunch of generic baddies in inventive ways. It’s a lot harder than it looks, since it calls for the lead actor to be fully committed to the role while being fully aware of how silly it all is. The fact that these guys aren’t “actors” in any real sense is no accident.

See also: the only real actor to take on such a role successfully: Liam Neeson, that poor bastard, who uses acting as therapy. (I don’t think it’s an accident that Neeson, too, was an athlete before he was an actor — Wiki just says he “discontinued” boxing at 17, but I read somewhere he was a real contender). Note also that Neeson’s Taken movies have a “real life” hook to them, human trafficking. They’re Schwarzenegger movies, and Neeson acquits himself well in them, but Neeson would fall flat on his face in all-out Arnold-style fantasies — a Conan or a Total Recall. Actors can’t make those movies; only entertainers can [cf. The A-Team, a role Arnold would’ve crushed].

In other words: you can make an “Arnold movie” without Arnold Schwarzenegger, the man, in the lead role, but you absolutely must have an entertainer as a leading man. Nothing could’ve saved the Total Recall “remake”, since it was clearly some other film with a tacked-on subplot to justify using the title, but Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson could’ve saved the Conan remake. It still wouldn’t have been very good — too self-consciously meta and gritty — but as a young guy trying to establish himself, poor ol’ Aquaman wasn’t up to it. He wanted to be a good actor; Arnold, in all his roles, just wanted to make a good movie. Arnold didn’t have to worry about his “performance”, because he was always just being Arnold (this seems to be the secret of Tom Cruise’s success, too). Aquaman had to worry about being taken seriously as an actor.

Severian, “The Entertainer”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-08.

April 25, 2023

QotD: What is military history?

The popular conception of military history – indeed, the conception sometimes shared even by other historians – is that it is fundamentally a field about charting the course of armies, describing “great battles” and praising the “strategic genius” of this or that “great general”. One of the more obvious examples of this assumption – and the contempt it brings – comes out of the popular CrashCourse Youtube series. When asked by their audience to cover military history related to their coverage of the American Civil War, the response was this video listing battles and reflecting on the pointless of the exercise, as if a list of battles was all that military history was (the same series would later say that military historians don’t talk about about food, a truly baffling statement given the important of logistics studies to the field; certainly in my own subfield, military historians tend to talk about food more than any other kind of historian except for dedicated food historians).

The term for works of history in this narrow mold – all battles, campaigns and generals – is “drums and trumpets” history, a term generally used derisively. The study of battles and campaigns emerged initially as a form of training for literate aristocrats preparing to be officers and generals; it is little surprise that they focused on aristocratic leadership as the primary cause for success or failure. Consequently, the old “drums and trumpets” histories also had a tendency to glory in war and to glorify commanders for their “genius” although this was by no means universal and works of history on conflict as far back as Thucydides and Herodotus (which is to say, as far back as there have been any) have reflected on the destructiveness and tragedy of war. But military history, like any field, matured over time; I should note that it is hardly the only field of history to have less respectable roots in its quite recent past. Nevertheless, as the field matured and moved beyond military aristocrats working to emulate older, more successful military aristocrats into a field of scholarly inquiry (still often motivated by the very real concern that officers and political leaders be prepared to lead in the event of conflict) the field has become far more sophisticated and its gaze has broadened to include not merely non-aristocratic soldiers, but non-soldiers more generally.

Instead of the “great generals” orientation of “drums and trumpets”, the field has moved in the direction of three major analytical lenses, laid out quite ably by Jeremy Black in “Military Organisations and Military Charge in Historical Perspective” (JMH, 1998). He sets out the three basic lenses as technological, social and organizational, which speak to both the questions being asked of the historical evidence but also the answers that are likely to be provided. I should note that these lenses are mostly (though not entirely) about academic military history; much of the amateur work that is done is still very much “drums and trumpets” (as is the occasional deeply frustrating book from some older historians we need not discuss here), although that is of course not to say that there isn’t good military history being written by amateurs or that all good military history narrowly follows these schools. This is a classification system, not a straight-jacket and I am giving it here because it is a useful way to present the complexity and sophistication of the field as it is, rather than how it is imagined by those who do not engage with it.

[…]

The technological approach is perhaps the least in fashion these days, but Geoffery Parker’s The Military Revolution (2nd ed., 1996) provides an almost pure example of the lens. This approach tends to see changing technology – not merely military technologies, but often also civilian technologies – as the main motivator of military change (and also success or failure for states caught in conflict against a technological gradient). Consequently, historians with this focus are often asking questions about how technologies developed, why they developed in certain places, and what their impacts were. Another good example of the field, for instance, is the debate about the impact of rifled muskets in the American Civil War. While there has been a real drift away from seeing technologies themselves as decisive on their own (and thus a drift away from mostly “pure” technological military history) in recent decades, this sort of history is very often paired with the others, looking at the ways that social structures, organizational structures and technologies interact.

Perhaps the most popular lens for military historians these days is the social one, which used to go by the “new military history” (decades ago – it was the standard form even back in the 1990s) but by this point comprises probably the bulk of academic work on military history. In its narrow sense, the social perspective of military history seeks to understand the army (or navy or other service branch) as an extension of the society that created it. We have, you may note, done a bit of that here. Rather than understanding the army as a pure instrument of a general’s “genius” it imagines it as a socially embedded institution – which is fancy historian speech for an institution that, because it crops up out of a society, cannot help but share that society’s structures, values and assumptions.

The broader version of this lens often now goes under the moniker “war and society”. While the narrow version of social military history might be very focused on how the structure of a society influences the performance of the militaries that created it, the “war and society” lens turns that focus into a two-way street, looking at both how societies shape armies, but also how armies shape societies. This is both the lens where you will find inspection of the impacts of conflict on the civilian population (for instance, the study of trauma among survivors of conflict or genocide, something we got just a bit with our brief touch on child soldiers) and also the way that military institutions shape civilian life at peace. This is the super-category for discussing, for instance, how conflict plays a role in state formation, or how highly militarized societies (like Rome, for instance) are reshaped by the fact of processing entire generations through their military. The “war and society” lens is almost infinitely broad (something occasionally complained about), but that broadness can be very useful to chart the ways that conflict’s impacts ripple out through a society.

Finally, the youngest of Black’s categories is organizational military history. If social military history (especially of the war and society kind) understands a military as deeply embedded in a broader society, organizational military history generally seeks to interrogate that military as a society to itself, with its own hierarchy, organizational structures and values. Often this is framed in terms of discussions of “organizational culture” (sometimes in the military context rendered as “strategic culture”) or “doctrine” as ways of getting at the patterns of thought and human interaction which typify and shape a given military. Isabel Hull’s Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (2006) is a good example of this kind of military history.

Of course these three lenses are by no means mutually exclusive. These days they are very often used in conjunction with each other (last week’s recommendation, Parshall and Tully’s Shattered Sword (2007) is actually an excellent example of these three approaches being wielded together, as the argument finds technological explanations – at certain points, the options available to commanders in the battle were simply constrained by their available technology and equipment – and social explanations – certain cultural patterns particular to 1940s Japan made, for instance, communication of important information difficult – and organizational explanations – most notably flawed doctrine – to explain the battle).

Inside of these lenses, you will see historians using all of the tools and methodological frameworks common in history: you’ll see microhistories (for instance, someone tracing the experience of a single small unit through a larger conflict) or macrohistories (e.g. Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization (2008)), gender history (especially since what a society views as a “good soldier” is often deeply wrapped up in how it views gender), intellectual history, environmental history (Chase Firearms (2010) does a fair bit of this from the environment’s-effect-on-warfare direction), economic history (uh … almost everything I do?) and so on.

In short, these days the field of military history, as practiced by academic military historians, contains just as much sophistication in approach as history more broadly. And it benefits by also being adjacent to or in conversation with entire other fields: military historians will tend (depending on the period they work in) to interact a lot with anthropologists, archaeologists, and political scientists. We also tend to interact a lot with what we might term the “military science” literature of strategic thinking, leadership and policy-making, often in the form of critical observers (there is often, for instance, a bit of predictable tension between political scientists and historians, especially military historians, as the former want to make large data-driven claims that can serve as the basis of policy and the later raise objections to those claims; this is, I think, on the whole a beneficial interaction for everyone involved, even if I have obviously picked my side of it).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Military History?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-11-13.

April 22, 2023

QotD: The yawning vaccuum that used to be “white culture”

Current Year White people are not allowed to have a culture. Any culture. Hence, in a perverse way, hipsterism.

First: I think we can agree that there’s no such thing as a black hipster, or a Latino hipster, or an Asian hipster. What would be the point? Those groups already have a culture, in both the “personal identity” and “grievance group” sense. […]

The 1990s were the last time there was some common ground. Growing up as I did in the Tech Boom South, I saw it firsthand. It was just accepted that your Hispanic (not “Latino”, and certainly not “LatinX”) friends would have certain cultural specific things they’d have to do from time to time. If you were friends, they might invite you. If they were good friends, they wouldn’t invite you (do not, under any circumstances, go to your buddy’s sister’s quinceañera. You will meet a whole bunch of hot, horny young Mexican nubiles. You will also meet their brothers and fathers and cousins and uncles and etc., so you will spend the whole evening running around like a homo, doing everything in your power not to talk to girls. It’s torture*).

Same thing with the Chinese kids, and the Indian kids, and all the rest. You’d never see your Asian buddies on Friday nights, because that’s when they had Chinese school (yes, of course their parents would schedule something academic on a Friday night). Diwali was cool, because your friends’ moms would make those crazy-sweet Indian desserts and send you a care package (also known as “diabetes in a box”). That was just an accepted part of life, the same way those guys wouldn’t start a pickup basketball game until after 10 on a Sunday morning, because they knew we’d be in church. Nobody thought much of it, in the same way all our moms just kinda learned by osmosis to keep tortilla chips and salsa in the cupboard as an all-purpose snack (no worries about anyone’s religious food prohibitions).

This worked, because there was still enough of a monoculture back then — this is the late 1980s / early 1990s — to provide common ground. Alas, as White culture disintegrated, the other guys started subsuming their cultural identities into their grievance group identities: The Chinese kids were worried about being called “bananas” (yellow on the outside, White on the inside); the Indian kids were ABCDs (American-Born Confused Desis); and so on. And the White kids were the most anti-White of all, since they’d gone to college for a semester or two and had learned how to parrot pop-Marxism (technically, pop-Gramscianism and pop-Frankfurt School-ism and pop-Marcuse, but who’s counting?).

Thinking back on it, those were the ostentatious “slackers”; the real “Grunge” kids — White kids who found their own Whiteness “problematic” (a phrase debuting in egghead circles around that time). I always assumed it was a problem with traditional, cock-rocking masculinity — not least because that’s what all the male “Grunge” rock stars said it was — but in retrospect I think it was a rising problem with Whiteness itself. Maybe all the grievance groups had a point, and maybe they didn’t, but either way the dominant Boomer culture sucks, so what else can you do?

I know how naive that must sound now, but 30 years ago …

* It wasn’t my buddy’s fault. He warned me. But c’mon, man — his mom invited me. We’d spent the whole summer working together on his dad’s landscaping crew; I practically lived at their house. What was I gonna say, no? Looking back on it, Mrs. Rodriguez was either trying to set me up with her daughter, or was Aztec goddess-level sadistic.

Severian, “To Mock It, It Must Exist”, Founding Questions, 2022-12-29.

April 15, 2023

QotD: When the pick-up artist became “coded right”

When did pickup artistry become criminal? Relying on online sex gurus for advice on persuading women into bed used to be seen as a fallback for introverted, physically unprepossessing “beta males”. And for this reason, in the 2000s, the discipline was promoted by the mainstream media as a way of instilling confidence in sexually-frustrated nerds. MTV’s The Pickup Artist shamelessly broadcast its tactics, with dating coaches encouraging young men to prey upon reluctant women, hoping to “neg” and “kino escalate” them into “number closes“. Contestants advanced through women of increasing difficulty (picking-up a stripper was regarded as “the ultimate challenge”) with the most-skilled “winning” the show.

Today, the global face of pickup artistry is Andrew Tate: sculpted former kickboxing champion, self-described “misogynist”, and, now, alleged human trafficker. Whatever results from the current allegations, his fall is a defining moment in the cultural history of the now inseparable worlds of the political manosphere and pickup artistry, and provides an opportunity to reflect upon their entangled history.

Pickup artistry burst onto the scene in the 2000s, propelled by the success of Neil Strauss’s best-selling book The Game. More a page-turning potboiler cataloguing the mostly empty lives of pickup artists (PUAs) than a how-to guide (though Strauss wrote one of those too), the methods in the book had been developed through years of research shared on internet forums. The “seduction underground”, as the large online community of people doing this research was called, then became the subject of widespread media attention. Through pickup artistry, the aggressive, formulaic predation of women was normalised as esteem boosting, and men such as those described in Strauss’s The Game could be viewed in a positive light: they had transformed from zero to hero and taken what was rightfully theirs.

The emergence of PUAs generated a swift backlash. The feminist blogs of the mid-to-late 2000s internet, of which publications like Jezebel still survive as living fossils, rushed to pillory them. The attacks weren’t without justification, but the world of PUAs during this period, much like the similarly wild-and-woolly bodybuilding forums, had no obvious political dimension beyond some sort of generic libertarianism. It was only after these initial critiques that it began to be coded as Right-wing by those on the Left. Duly labelled, PUAs and other associated manosphere figures drifted in that direction. MTV’s dating coaches were not part of the political landscape, merely feckless goofballs and low-level conmen capable of entertaining the masses. But their successors would be overtly political actors.

Oliver Bateman, “Why pick-up artists joined the Online Right”, UnHerd, 2023-01-08.

April 1, 2023

Athenian or Visigoth? Western civilization or barbarism?

Jon Miltimore recalls Neil Postman’s 1988 essay titled “My Graduation Speech”, which seems even more relevant today than when he wrote it:

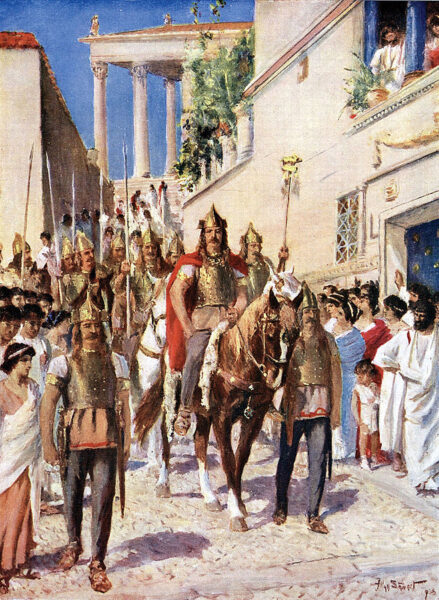

Alaric, King of the Visigoths, entering Athens in 395 AD.

Public domain illustration originally published in the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1920 via Wikimedia Commons.

What seemed to bother Postman was a nagging suspicion that modern humans were taking civilization for granted. This sentiment was more clearly expressed in one of Postman’s less-known literary works, his 1988 essay titled “My Graduation Speech“.

In his speech, Postman discusses two historic civilizations familiar to most people today — Athenians and Visigoths. One group, the Athenians, thrived about 2,300 years ago. The other, the Visigoths, made their mark about 1,700 years ago. But these civilizations were separated by much more than time, Postman explained.

The Athenians gave birth to a cultural enlightenment whose fruits are still visible today — in our art, education, language, literary works, and architecture. The Visigoths, on the other hand, are notable mostly for the destruction of civilization.

Postman mentions these peoples because, he argued, they still survive today. Here is what he wrote:

I do not mean, of course, that our modern-day Athenians roam abstractedly through the streets reciting poetry and philosophy, or that the modern-day Visigoths are killers. I mean that to be an Athenian or a Visigoth is to organize your life around a set of values. An Athenian is an idea. And a Visigoth is an idea.

But what ideas? What values? Postman explains:

To be an Athenian is to hold knowledge and, especially the quest for knowledge in high esteem. To contemplate, to reason, to experiment, to question — these are, to an Athenian, the most exalted activities a person can perform. To a Visigoth, the quest for knowledge is useless unless it can help you to earn money or to gain power over other people.

To be an Athenian is to cherish language because you believe it to be humankind’s most precious gift. In their use of language, Athenians strive for grace, precision, and variety. And they admire those who can achieve such skill. To a Visigoth, one word is as good as another, one sentence in distinguishable from another. A Visigoth’s language aspires to nothing higher than the cliché.

To be an Athenian is to understand that the thread which holds civilized society together is thin and vulnerable; therefore, Athenians place great value on tradition, social restraint, and continuity. To an Athenian, bad manners are acts of violence against the social order. The modern Visigoth cares very little about any of this. The Visigoths think of themselves as the center of the universe. Tradition exists for their own convenience, good manners are an affectation and a burden, and history is merely what is in yesterday’s newspaper.

To be an Athenian is to take an interest in public affairs and the improvement of public behavior. Indeed, the ancient Athenians had a word for people who did not. The word was idiotes, from which we get our word “idiot”. A modern Visigoth is interested only in his own affairs and has no sense of the meaning of community.

Postman said all people must choose whether to be an Athenian or a Visigoth. But how does one tell one from the other? One might be tempted to think that education is the proper path to becoming an Athenian. Alas, Postman argued that this was not the case.

I must tell you that you do not become an Athenian merely by attending school or accumulating academic degrees. My father-in-law was one of the most committed Athenians I have ever known, and he spent his entire adult life working as a dress cutter on Seventh Avenue in New York City. On the other hand, I know physicians, lawyers, and engineers who are Visigoths of unmistakable persuasion. And I must also tell you, as much in sorrow as in shame, that at some of our great universities, perhaps even this one, there are professors of whom we may fairly say they are closet Visigoths.

Postman concluded his speech by expressing his wish that the student body to which he was speaking would graduate more Athenians than Visigoths.

The production of educated barbarians was relatively low in 1988, despite Postman’s pessimism. The production of such modern-day Visigoths is unimaginably higher now than the tail end of the Cold War when he was writing. I fear we have already made our decision … and may God have mercy upon our souls.

March 28, 2023

WEIRD World – basing all our “assumptions about human nature on psych lab experiments starring American undergraduates”

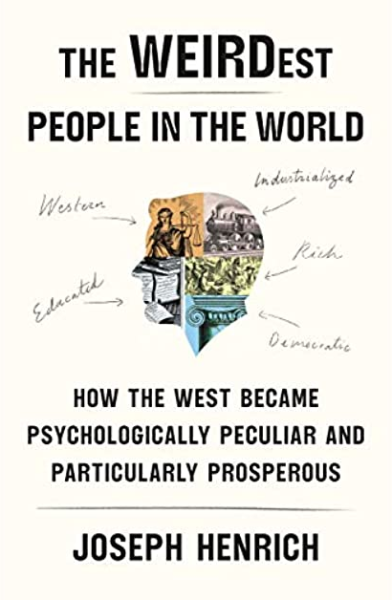

Jane Psmith reviews The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous by Joseph Henrich:

Until 2002, diplomats at the United Nations didn’t have to pay their parking tickets. Double-parking, blocking a fire hydrant, blocking a driveway, blocking an entire midtown Manhattan street — it didn’t matter; when you have diplomatic plates, they let you do it. In the five years before State Department policy changed in November 2002, UN diplomats racked up a whopping 150,000 unpaid parking tickets worth $18 million in fines. (Among other things, the new policy allowed the city to have 110% of the amount due deducted from the US foreign aid budget to the offending diplomats’ country. Can you believe they never actually did it? Lame.) Anyway, I hope you’re not going to be surprised when I say that the tickets weren’t distributed evenly: the nine members of Kuwait’s UN mission averaged almost 250 unpaid tickets apiece per year (followed by Egypt, Chad, Sudan, Bulgaria, and Mozambique, each between 100 and 150; the rest of the top ten were Albania, Angola, Senegal, and Pakistan). The UK, Canada, Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Norway had none at all. The rest of the rankings are more or less what you’d expect: for example, Italy averaged three times as many unpaid tickets per diplomat as France and fifteen times as many as Germany.

What did the countries with the fewest unpaid parking tickets have in common? Well, they generally scored low on various country corruption indexes, but that’s just another way of saying something about their culture. And the important thing about their culture is that these countries are WEIRD: western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. But they’re also, in the grand scheme of human history, weird: their inhabitants think differently, behave differently, and value different things than most humans. Among other things, WEIRD people are individualistic, nonconformist, and analytical. They — okay, fine, we — are particularly hard-working, exhibit low time preference, prefer impersonal rules we apply universally, and elevate abstract principles over contextual and relationship-based standards of behavior. In other words, WEIRD people (as Joseph Henrich and his colleagues pointed out in the influential 2010 paper where they coined the phrase) are outliers on almost every measure of human behavior. Wouldn’t it be silly for an entire academic discipline (and therefore an entire society ideologically committed to Trusting The Experts) to base all its assumptions about human nature on psych lab experiments starring American undergraduates? That would give us a wildly distorted picture of what humans are generally like! We might even do something really dumb like assume that the social and political structures that work in WEIRD countries — impersonal markets, constitutional government, democratic politics — can be transplanted wholesale somewhere else to produce the same peace and prosperity we enjoy.

Ever since he pointed out the weirdness of the WEIRD, Henrich has been trying to explain how we got this way. His argument really begins in his 2015 The Secret of Our Success, which I reviewed here and won’t rehash. If you find yourself skeptical that material circumstances can drive the development of culture and psychology (unfortunately the term “cultural Marxism” is already taken), you should start there. Here I’m going to summarize the rest of Henrich’s argument fairly briefly: first, because I don’t find it entirely convincing (more on that below), and second, because I’m less interested in how we got WEIRD than in whether we’re staying WEIRD. The forces that Henrich cites as critical to the forging of WEIRD psychology are no longer present, and many of the core presuppositions of WEIRD culture are no longer taken for granted, which raises some thought-provoking questions. But first, the summary.

Henrich argues that the critical event setting the West on the path to Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic was the early medieval western Church’s ban on cousin marriage. That might seem a little odd, but bear in mind that most of the humans who’ve ever lived have been enmeshed in incredibly dense kin networks that dictate obligations, responsibilities, and privileges: your identity is given from birth, based simply on your role as a node in an interdependent network. When societies grow beyond the scale of a family, it’s by metaphorically extending and intensifying these kinship bonds (go read our review of The Ancient City for more on this). These kinship networks perpetuate themselves through marriage, and particularly through marriage to relatives, whether blood or in-laws, to strengthen existing connections. Familial or tribal identities come first, before even the claims of universal religions, as when Wali Khan, a Pakistani politician, phrased his personal allegiances as “I have been a Pashtun for six thousand years, a Muslim for thirteen hundred years, and a Pakistani for twenty-five.” You could imagine Edwin of Northumbria or Childeric saying something pretty similar.

Then, beginning in the 4th century, the western Church began to forbid marriages to relatives or in-laws, the kinship networks began to wither away, and alternative social technologies evolved to take their place. In place of the cousin-marriers’ strong tight bonds, conformity, deference to traditional authority, and orientation toward the collective, you get unmoored individuals who have to (or get to, depending on your vantage point) create their own mutually beneficial relationships with strangers. This promotes a psychological emphasis on personal attributes and achievements, greater personal independence, and the development of universalist social norms. Intensive kinship creates a strong in-group/out-group distinction (there’s kin and there’s not-kin): people from societies with strong kinship bonds, for instance, are dramatically more willing to lie for a friend on the witness stand. WEIRD people are almost never willing to do that, and would be horrified to even be asked. Similarly, in societies with intensive kinship norms, you’d be considered immoral and irresponsible if you didn’t use a position of power and influence to benefit your family or tribe; WEIRD people call that nepotism or corruption and think it’s wrong.

March 27, 2023

The war against fertility

The effacement of women’s bodies is changing from a cultural signal to a battlefield maneuver. The acceleration of the presence of men as dominant participants in women’s sports, the growing intensity of casually monstrous blue zone attacks on families and parenting, the emergence of drag queens — men playacting as women, burlesque cartoons about sexual identity — as The Most Important Symbol Ever (and something children should definitely see) …

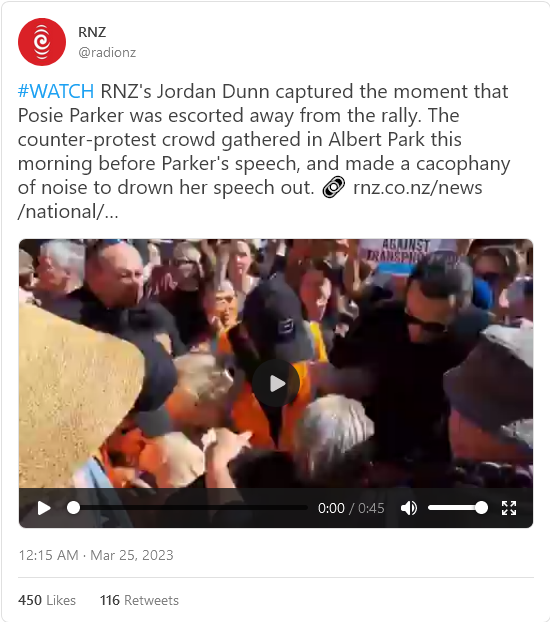

… and now this:

That’s footage from a Let Women Speak event in Auckland, New Zealand, where women arguing that “women” are “adult human females” were physically attacked by a mob of “transwomen” — by men — and their allies. It’s very progressive when men dressed as women silence women and hurt them. More here, also linked above.

In the opening paragraph of this post, you may have thought that one of the things I mentioned was different than the other things — that the blue state assault on families and parenting isn’t specifically gendered, and is equally an assault on the role of mothers and fathers. And it is. But.

It seems to me that the very very strange thing breaking out all over the world — or all over the Anglosphere, because I don’t see Nigeria and Peru and Singapore going all-in on transgendered everything — is loaded with subtext about a febrile loathing for fertility. In policy, we’re incentivizing childlessness, and disincentivizing childbearing. Birthrates are declining sharply, and were declining even before the mRNA injections, while blue state governments work on laws that tell would-be parents their children can vanish from their custody on political pretexts. Who has the future children while the state says that hey, nice family you have there, be a shame if something were to happen to it?

I suspect the reason so much hate and rage is being directed at women is that their bodies can produce babies, which means that the hate and rage is being directed at the future. Peachy Keenan, who’s all over this stuff in multiple forums, wrote recently about Hicklibs on Parade, describing “how deeply the postmodern, anti-human gender ideology has penetrated into what we used to call ‘middle America'”:

In Plano, Texas last fall, an “all-ages” drag brunch attracted some unwanted attention from people who thought they lived in a conservative state. At the brunch — which was held at Ebb & Flow, an eatery in an upscale strip mall — a buffoonish man in a dress wearing cat ears sings, “My p*ssy good, p*ssy sweet, p*ssy good enough to eat”, while flashing his underwear.

In the video from the event, a four-year old girl stares in shock as the “drag” performer twerks and grinds for the ladies in attendance.

The people in the crowd watching this man systematically strip away a little girl’s innocence look like nice friendly Texans; plump grandmas and families and the types you’d run into at the local Costco. They are not hipsters; they are not edgy. They look normal!

This is what makes all of this so striking. These slightly downmarket Texan and Midwestern prairie home companion women have, historically, been the only thing holding this rickety old country together.

March 16, 2023

QotD: “In the tattoo parlour, the customer is always wrong”

There’s only one thing worse than slavery, of course, and that’s freedom. I don’t mean, I hasten to add, my own freedom, to which I am really rather attached; no, it is other people’s freedom, and what they choose to do with it, that appalls me. They have such bad taste. The notion of self-expression has much to answer for. It gives people the presumptuous notion that somewhere deep inside them there is a genius trying to get out. This genius, at least round here, expresses itself mainly by drinking too much, taking drugs, tattooing its skin and piercing its body. On the whole, I think, the self is best not expressed and, like children, should be neither seen nor heard.

One day, I arrived on the ward to discover an enthusiastic self-expresser in the first bed. Her two-inch-long nails were painted lime green, and looked as if they gave off the kind of radiation that meant instant leukaemia. That, however, was the least of it.

She was lying in the bed, décolleté, to reveal breasts pierced with many metal bars ending in steel balls to keep them in place, and for what is known round here as decoration. I couldn’t look at them without wincing; ex-President Clinton would no doubt have felt her pain. As for her face, it was the modern equivalent of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. It was also the refutation of the doctrine that the customer is always the right. In the tattoo parlour, the customer is always wrong.

She had a ring through the septum of her nose, and a ring through her upper lip, so that the two clacked when she spoke. She had a stud in her tongue, and two studs through her lower lip. She had so many rings through her ears that they looked like solenoids. She had a metal bar through the bridge of her nose and rings at the outer edges of her eyebrows. If she were to die, she could probably be sold to a scrap metal merchant.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Lady of the Rings”, Asian Age, 2005-12-27.

March 15, 2023

QotD: The coming generation isn’t the Millennials … it’s Gen X

The reason this matters is: The whole thing now — St. George Floyd, the Kung Flu, the Seattle “autonomous zone”, all of it — is being portrayed as the revolt of the New New Left against the Old Left. It’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez vs. Nancy Pelosi (born 1940) … but lost in all of this is the fact that the next generation to take power won’t be the Millennials, it’ll be the Gen Xers. Those people born between 1965 and 1980(-ish)? You know, the “Slackers”? Did we all just kinda, umm, forget about them?

That’s your next layer of political and social control. The youngest of us are in their late 30s (again, using the broadest definition); most of us are well into middle age, and some of us are plunging headfirst into late middle age. The chiefs of police, the military’s senior staff officers (including, by now, some general and flag officers), the CEOs and CFOs … they’re not Millennials, they’re Xers.

Admittedly we’re a forgettable bunch. We didn’t get a chance at natural, healthy teenage rebellion, because our parents, the goddamn Boomers, claimed a monopoly on rebellion, so we had to be all, you know, like, whatever about it. The Boomers thought Andy Warhol was a serious artist and Bob Dylan a talented musician; is it any wonder that Kurt Cobain’s godawful caterwauling was the best we could do?

All of that is water under the bridge, of course. But here’s where it gets really, really meta: This great social upheaval is, for us, a copy of a copy. It’s people who were actually alive in the 1960s cosplaying The Sixties™ — just like they did the entire time we were growing up. Just as we had no template for teenage rebellion, we don’t really have a template for riots and whatnot either. Some of us have decided to crank it up to eleven — all of the most obnoxious Karens are Gen Xers — but lots of us … haven’t. I really have no idea just what the majority of my generational cohort is doing right now while our most vocal idiots are out Karening, in much the same way I have no idea what the majority of Silents were doing while the Chicago Seven were out doing their thing.

All I know is, there’s an entire layer of political power between AOC and Pelosi. We haven’t really seen it up until now, but it’s there. Is Gen X finally, at long last, going to get its shit together? I suspect that the real drama is still waiting in the wings.

Severian, “Talkin’ ’bout My Generation!”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-06-11.

March 13, 2023

QotD: The components of an oath in pre-modern cultures

Which brings us to the question how does an oath work? In most of modern life, we have drained much of the meaning out of the few oaths that we still take, in part because we tend to be very secular and so don’t regularly consider the religious aspects of the oaths – even for people who are themselves religious. Consider it this way: when someone lies in court on a TV show, we think, “ooh, he’s going to get in trouble with the law for perjury”. We do not generally think, “Ah yes, this man’s soul will burn in hell for all eternity, for he has (literally!) damned himself.” But that is the theological implication of a broken oath!

So when thinking about oaths, we want to think about them the way people in the past did: as things that work – that is they do something. In particular, we should understand these oaths as effective – by which I mean that the oath itself actually does something more than just the words alone. They trigger some actual, functional supernatural mechanisms. In essence, we want to treat these oaths as real in order to understand them.

So what is an oath? To borrow Richard Janko’s (The Iliad: A Commentary (1992), in turn quoted by Sommerstein [in Horkos: The Oath in Greek Society (2007)]) formulation, “to take an oath is in effect to invoke powers greater than oneself to uphold the truth of a declaration, by putting a curse upon oneself if it is false”. Following Sommerstein, an oath has three key components:

First: A declaration, which may be either something about the present or past or a promise for the future.

Second: The specific powers greater than oneself who are invoked as witnesses and who will enforce the penalty if the oath is false. In Christian oaths, this is typically God, although it can also include saints. For the Greeks, Zeus Horkios (Zeus the Oath-Keeper) is the most common witness for oaths. This is almost never omitted, even when it is obvious.

Third: A curse, by the swearers, called down on themselves, should they be false. This third part is often omitted or left implied, where the cultural context makes it clear what the curse ought to be. Particularly, in Christian contexts, the curse is theologically obvious (damnation, delivered at judgment) and so is often omitted.

While some of these components (especially the last) may be implied in the form of an oath, all three are necessary for the oath to be effective – that is, for the oath to work.

A fantastic example of the basic formula comes from Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (656 – that’s a section, not a date), where the promise in question is the construction of a new monastery, which runs thusly (Anne Savage’s translation):

These are the witnesses that were there, who signed on Christ’s cross with their fingers and agreed with their tongues … “I, king Wulfhere, with these king’s eorls, war-leaders and thanes, witness of my gift, before archbishop Deusdedit, confirm with Christ’s cross” … they laid God’s curse, and the curse of all the saints and all God’s people on anyone who undid anything of what was done, so be it, say we all. Amen.” [Emphasis mine]

So we have the promise (building a monastery and respecting the donation of land to it), the specific power invoked as witness, both by name and through the connection to a specific object (the cross – I’ve omitted the oaths of all of Wulfhere’s subordinates, but each and every one of them assented “with Christ’s cross”, which they are touching) and then the curse to be laid on anyone who should break the oath.

Of the Medieval oaths I’ve seen, this one is somewhat odd in that the penalty is spelled out. That’s much more common in ancient oaths where the range of possible penalties and curses was much wider. The Dikask‘s oath (the oath sworn by Athenian jurors), as reconstructed by Max Frankel, also provides an example of the whole formula from the ancient world:

I will vote according to the laws and the votes of the Demos of the Athenians and the Council of the Five Hundred … I swear these things by Zeus, Apollo and Demeter, and may I have many good things if I swear well, but destruction for me and my family if I forswear.

Again, each of the three working components are clear: the promise being made (to judge fairly – I have shortened this part, it goes on a bit), the enforcing entity (Zeus, Apollo and Demeter) and the penalty for forswearing (in this case, a curse of destruction). The penalty here is appropriately ruinous, given that the jurors have themselves the power to ruin others (they might be judging cases with very serious crimes, after all).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Oaths! How do they Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-28.

March 10, 2023

The evolution of a slur

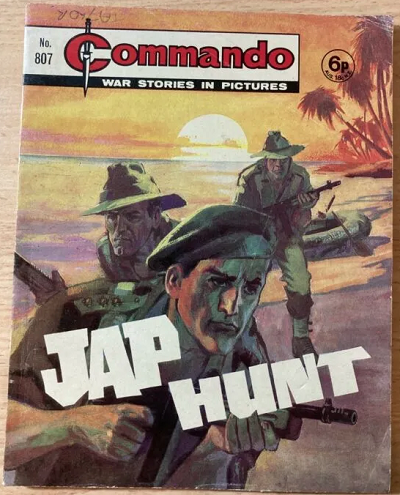

Scott Alexander traces the reasons that we can comfortably call British people “Brits” but avoid using the similar contraction “Japs” for Japanese people:

Someone asks: why is “Jap” a slur? It’s the natural shortening of “Japanese person”, just as “Brit” is the natural shortening of “British person”. Nobody says “Brit” is a slur. Why should “Jap” be?

My understanding: originally it wasn’t a slur. Like any other word, you would use the long form (“Japanese person”) in dry formal language, and the short form (“Jap”) in informal or emotionally charged language. During World War II, there was a lot of informal emotionally charged language about Japanese people, mostly negative. The symmetry broke. Maybe “Japanese person” was used 60-40 positive vs. negative, and “Jap” was used 40-60. This isn’t enough to make a slur, but it’s enough to make a vague connotation. When people wanted to speak positively about the group, they used the slightly-more-positive-sounding “Japanese people”; when they wanted to speak negatively, they used the slightly-more-negative-sounding “Jap”.

At some point, someone must have commented on this explicitly: “Consider not using the word ‘Jap’, it makes you sound hostile”. Then anyone who didn’t want to sound hostile to the Japanese avoided it, and anyone who did want to sound hostile to the Japanese used it more. We started with perfect symmetry: both forms were 50-50 positive negative. Some chance events gave it slight asymmetry: maybe one form was 60-40 negative. Once someone said “That’s a slur, don’t use it”, the symmetry collapsed completely and it became 95-5 or something. Wikipedia gives the history of how the last few holdouts were mopped up. There was some road in Texas named “Jap Road” in 1905 after a beloved local Japanese community member: people protested that now the word was a slur, demanded it get changed, Texas resisted for a while, and eventually they gave in. Now it is surely 99-1, or 99.9-0.1, or something similar. Nobody ever uses the word “Jap” unless they are either extremely ignorant, or they are deliberately setting out to offend Japanese people.

This is a very stable situation. The original reason for concern — World War II — is long since over. Japanese people are well-represented in all areas of life. Perhaps if there were a Language Czar, he could declare that the reasons for forbidding the word “Jap” are long since over, and we can go back to having convenient short forms of things. But there is no such Czar. What actually happens is that three or four unrepentant racists still deliberately use the word “Jap” in their quest to offend people, and if anyone else uses it, everyone else takes it as a signal that they are an unrepentant racist. Any Japanese person who heard you say it would correctly feel unsafe. So nobody will say it, and they are correct not to do so. Like I said, a stable situation.

He also explains how and when (and how quickly) the use of the word “Negro” became extremely politically incorrect:

Slurs are like this too. Fifty years ago, “Negro” was the respectable, scholarly term for black people, used by everyone from white academics to Malcolm X to Martin Luther King. In 1966, Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael said that white people had invented the term “Negro” as a descriptor, so people of African descent needed a new term they could be proud of, and he was choosing “black” because it sounded scary. All the pro-civil-rights white people loved this and used the new word to signal their support for civil rights, soon using “Negro” actively became a sign that you didn’t support civil rights, and now it’s a slur and society demands that politicians resign if they use it. Carmichael said — in a completely made up way that nobody had been thinking of before him — that “Negro” was a slur — and because people believed him it became true.

QotD: Wine in French culture

Wine is obviously hugely central to French culture. In 1965 French adults consumed 160 litres per head a year, which perhaps explains their traditionally very high levels of cirrhosis. Despite this, they don’t have the sort of extreme oblivion-seeking alcoholism found in the British Isles. Anglo-Saxon binge drinking is considered uncouth, and the true man of panache and élan instead spends all day mildly sozzled until eventually turning into a grotesque Gérard Depardieu figure. (Although Depardieu’s 14 bottles of wine a day might be on the high side, even for French standards.)

When the French sought to reduce alcohol consumption in the 1950s, the government’s slogan was “No more than a litre of wine a day“, which must have seemed excessively nanny-statish at a time when primary school children were given cider for lunch. Wine consumption has quite drastically fallen in the decades since, by as much as two-thirds by some estimates.

Ed West, “The Frenchest things in the world … Part Deux”, Wrong Side of History, 2022-12-09.