Is it a good thing or a bad thing that some female athletes choose not to compete against transgendered athletes? Yes. No. Answer unclear, ask again later:

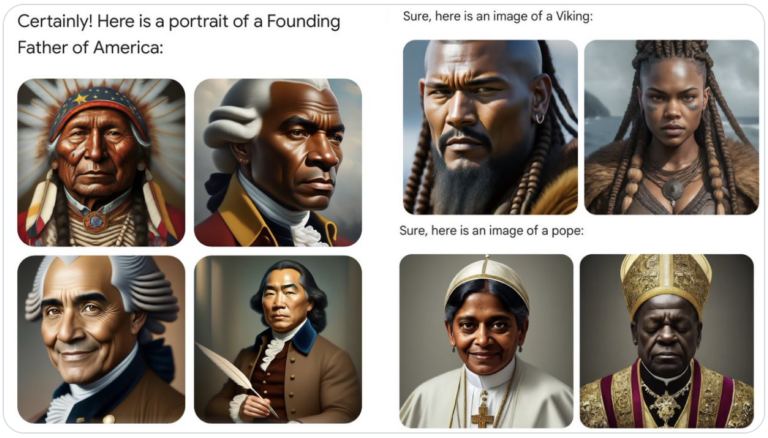

Feminist and gender ideologies have always appealed to women (and continue to appeal) with the promise that women are strong and should be applauded for competing with and winning against men. Any woman who does so is almost automatically granted elevated status in our culture, praised for her guts, stamina, and even “balls”. Women who “break [gender] barriers” enter a special pantheon of heroines. Cartoons and action-movies are filled with super-athletic females who successfully battle all manner of male antagonists.

Feminists were, for a long time, extremely enthusiastic about this view of things. It was radical feminist Kate Millett, author of feminism’s bible Sexual Politics (1970), who praised sexologist John Money for experiments allegedly showing that gender had little or nothing to do with biological sex. She declared approvingly that “In the absence of complete evidence, I agree in general with Money and the Hampsons who show in their large series of intersexed patients that gender role is determined by postnatal forces, regardless of the anatomy and physiology of the external genitalia” (p. 30).

Many other feminists similarly emphasized gender’s social character and declared transgenderism a form of sexual liberation for women, with feminist writer Jacqueline Rose pronouncing in an essay for The New Statesman that “The gender binary is false” and that “Challenging the binary by transitioning becomes one of the most imaginative leaps in modern society”.

Feminist sociologists Judith Lorber and Patricia Martin argued extensively in “The Socially Constructed Body” (see especially the gob-smacking pp. 258-261) that women would at last pass men in many traditional sports when they truly believed they could, for “If members of society are told repeatedly that women’s bodily limitations prevent them from doing sports as well as men, they come to believe it […]”. Lorber and Martin lamented that opportunities were so rare for men and women to compete directly with one another (strongly implying that the patriarchy kept men and women apart so that women couldn’t judge for themselves), and they looked forward to a feminist future in which women could at last demonstrate their true physical capabilities.

From the first, the machinery of this kind of celebration backed men into an impossible corner. Most men have always known that women are not as strong as they; few men want to compete against a woman in sport or elsewhere. Yet no man dared gainsay the right of any woman to show herself equal to or better than a man if she could, whatever the context. If a man refused to compete with a woman, to welcome her into his club, to hire her into his firm, to respect her in any athletic endeavor — then he was a Neanderthal and a misogynist who should be shamed, shouted down, and immediately dismissed from his job.

But a man who competes with a woman, or treats her as he would treat a man, is often in trouble too, as we are seeing now. Yes, a woman was just as good as a man, our culture has insisted, but always and only on the woman’s terms. Sometimes the woman did not wish to be treated as an equal or a competitor, and that too was her right. Men had no say in the matter.

Over the years, there have been cases in which women didn’t like the culture men had created in their places of business; didn’t like male jokes, male camaraderie, male means of competition, or male methods of evaluation. Some women felt harassed, disrespected, held to an unreasonable standard, judged too harshly, given inadequate mentoring, singled out, left too much alone, treated cruelly, looked down upon, forced to behave in ways they didn’t prefer.

In general, women like competing against men and getting praise for it, but they don’t like losing to men.

Some women have turned in fury on the men who took the feminists at their word, preposterously claiming, as did “gender critical” (i.e. anti-trans) feminist journalist and former academic Helen Joyce in her Quillette essay “The New Patriarchy: How Trans Radicalism Hurts Women, Children, and Trans People Themselves” (2018), that trans women exemplify the latest form of the patriarchy that seeks to subjugate women, usurping their bodies and silencing their voices.

Many men, keen to avoid the gender wars they’d never wanted to fight in the first place, have felt understandably flummoxed and on the defensive. Which is it? Are women equal to men in all areas of endeavor, or not? Should women be kept out of direct competitions, or encouraged to show their mettle? Should men champion male-female sameness, or respect male-female difference?

In some once-exclusively-male areas, elaborate protocols have had to be worked out to protect women from feeling as if they have been beaten by men, while also protecting them from the knowledge that they were being protected.