In the Nineteenth Century, intellectuals raised the argument that Western Civilization was wrong about all its major conclusions, from Christianity to Democracy to Capitalism, and that a rational system of scientific socialism should and would correct these errors and replace them.

This, over the next hundred years, was attempted, with the result that in a single generation the socialists and communists and national socialists of various stripes had killed more people and wrought more ruin than all world religions combined during all the previous generations of history.

Meanwhile, the visual arts were reduced to aberrant rubbish not merely ugly and untalented, but objectively indistinguishable from the work of schizophrenics; literature reduced to porn and tales of failure and decay; science was reduced from an honest and objective pursuit of truth to a whorish tool servicing political ends, particularly the ends of environmentalist hysterics, but creeping into other areas; universities degenerated from bastions of learning protected by traditions of academic freedom to the foremost partisans in favor of speech codes and political correctness; family life was and continues to be assaulted; abortion continues to carry out a slow and silent genocide of negro babies, girl babies, and other unwanted humanoids; law enforcement has been redirected from protecting the innocent because they are innocent to protecting the guilty because they are guilty; the Fair Deal and New Deal of the socialist philosophy at its height of intellectual respectability did nothing but prolong what should have been a ten month market correction into a Great Depression that lasted ten years; Welfare programs encouraged, exacerbated, and created a permanent and unelevatable underclass in America, ruining the very lives the programs were alleged to help; Affirmative Action has made race-hatred, accusations of racism, and race-baiting a permanent part of American life, despite that no less racist nation ever has nor ever could exist.

So the Left has not only failed in everything they attempted, and failed at every promise they made, they failed in an immense, astonishing, unparalleled, and horrifying way, a way so deep and so vast and so gross as to never have been seen before in history nor ever imagined before, not even by science fiction writers. Even Orwell did not foretell of a time when men would voluntarily adopt Newspeak and Doublethink and all the apparatus of oppression, freely and without coercion. Even he, the most famous writers of dystopia of all time, could not imagine the modern day. The failure of the Left is indescribable: one can only grope for words like ‘awe-inspiring’ or ‘astronomical’ to express the magnitude. If Lot’s wife were to look steadily at what the Left has done, she would turn to a pillar of salt, so horrifying, so overwhelming, so dazzling is the hugeness of failure.

Now, when your prediction and worldview and way of life and philosophy turns out to be an utter failure of epic, nay, apocalyptic proportions, you have one of two choices. The honest choice is to return to the drawing board of your mind, and recalculate your ideas from their assumptions, changing any assumptions that prove false to facts.

Pardon me. I have to stop typing for a moment. The idea of a Leftwinger actually doing this honest mental act is so outrageous, that I am overcome by a paroxysm of epileptic laughter, and must steady myself ere I faint.

John C. Wright, “Unreality and Conformity of the Left”, Everyjoe, 2015-07-05.

March 13, 2017

QotD: The legacy of nineteenth century intellectualism

January 27, 2017

Monty Python – Coal Miner Son

Published on Apr 23, 2014

World renowned blue-collar play-wright at odds with his elitist coal-mining son.

H/T to Megan McArdle for the link.

January 12, 2017

How we experience art

Terry Teachout posted a link to this older column about “blockbuster” art exhibitions and he offered a few suggestions:

(1) Once a year, every working art critic should be required to attend a blockbuster show on a weekend or holiday. He should buy a ticket with his own money, line up with the citizenry, fight his way through the crowds, listen to an audio tour – and pay close attention to what his fellow museumgoers are saying and doing. In short, he should be forced to remind himself on a regular basis of how ordinary people experience art, and marvel at the fact that they keep coming back in spite of everything.

That one’s easy. This one’s harder:

(2) Every “civilian” who goes to a given museum at least six times a year should be allowed to attend a press or private view of a major exhibition. The experience of seeing a blockbuster show under such conditions is eye-opening in every sense of the word. If more ordinary museumgoers were to have such experiences, it might change their feelings about the ways in which museums present such exhibitions.

Lastly, I’ll take a flying leap into the cesspool of arrant idealism:

(3) No museum show should contain more than 75 pieces, and no museum should be allowed to present more than one 75-piece show per year. Tyler Green […] wrote the other day to tell me that Washington’s Phillips Collection, our favorite museum, is putting on a Milton Avery retrospective in February that will contain just 42 pieces. I can’t wait to see it, not only because I love Avery but because that is exactly the right size for an exhibit of that kind – big enough to cover all the bases, but not too big to swamp the viewer and dull his responses.

I’ll close with a memory. A few years ago, I gave a speech in Kansas City, and as part of my fee I was given a completely private tour of the Nelson-Atkins Museum. I went there after hours and was escorted by one of the curators, who switched on the lights in each gallery as we entered and switched them off as we left. I can’t begin to tell you what an astonishing and unforgettable impression that visit made on me. To see masterpieces of Western art in perfect circumstances is to realize for the first time how imperfectly we experience them in our everyday lives. It changes the way you feel about museums – and about art itself. I didn’t realize it then, but that private view undoubtedly helped to put me on the road to buying art.

Perhaps one of our great museums might consider raffling off a dozen such tours each year. I’m not one for lotteries, but I’d definitely pony up for a ticket.

December 18, 2016

QotD: The new Whitney Museum in New York City

On a recent visit to New York City, I had the opportunity to walk around the exterior of the new Whitney Museum, built at a cost of $442 million. It is a monument of a kind: to the vanity, egotism, and aesthetic incompetence of celebrity architects such as Renzo Piano, and to the complete loss of judgment and taste of modern patrons.

If it were not a tragic lost opportunity (how often do architects have the chance to build an art gallery at such cost?), it would be comic. I asked the person with whom I was walking what he would think the building was for if he didn’t know. The façade — practically without windows — looked as if it could be the central torture chambers of the secret police, from which one half expects the screams of the tortured to emerge. Certainly, it was a façade for those with something to hide: perhaps appropriately so, given the state of so much modern art.

The building was a perfect place from which to commit suicide, with what looked like large diving boards emerging from the top of the building, leading straight to the ground far below. Looking up at them, one could almost hear in one’s mind’s ear the terrible sound of the bodies as they landed on the ground below. There were also some (for now) silvery industrial chimneys, leading presumably from the incinerators so necessary for the disposal of rubbishy art. The whole building lacked harmony, as if struck already by an earthquake and in a half-collapsed state; it’s a tribute to the imagination of the architect that something so expensive should be made to look so cheap. It is certain to be shabby within a decade.

Theodore Dalrymple, “A Monument to Tastelessness: The new Whitney Museum looks like a torture chamber”, City Journal, 2015-04-22.

November 23, 2016

When is an American Indian artist not American Indian?

Answer: when federal bureaucratic rules interact unhappily with state-level bureaucratic rules. Eric Boehm explains why an artist is not legally allowed to market her beadwork as “American Indian-made”:

Peggy Fontenot is an American Indian artist, of that there can be no doubt.

She’s a member of the Patawomeck tribe. She’s taught traditional American Indian beading classes in Native American schools and cultural centers in several states. Her work has been featured in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the Native American.

In Oklahoma, though, she’s forbidden from calling her art what it plainly is: American Indian-made.

A state law, passed earlier this year, forbids artists from marketing their products in Oklahoma as being “American Indian-made” unless the artist is a member of a tribe recognized by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The Patawomeck tribe is recognized by the state of Virginia, but not by the federal government. Fontenot says she can trace her Native American heritage back to the 16th Century, when the tribe was one of the first to welcome settlers from Europe who landed on the east coast of Virginia. She’s been working as an artist since 1983, doing photography, beading, and making jewelry.

[…]

According to PLF [Pacific Legal Foundation], Oklahoma’s law could affect as many as two-thirds of all artists who are defined American Indians under federal law. The state law also violates the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause by restricting the interstate American Indian art market, the lawsuit contends.

August 17, 2016

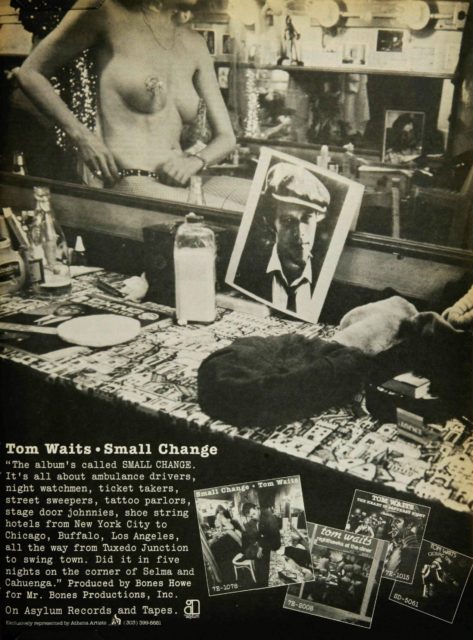

Cover art and outtakes from Tom Waits’ Small Change, 1976

I didn’t know that the “go-go dancer” in the background of the photos from Tom Waits’ album Small Change was Cassandra Peterson (better known for her portrayal of “Elvira” to most of us):

A couple of outtakes at the link.

August 3, 2016

QotD: The lure of “new” old art

What is it about stories like these [the discovery of “lost” artistic masterworks] that we find so unfailingly seductive? No doubt the Antiques Roadshow mentality is part of it. All of us love to suppose that the dusty canvas that Aunt Tillie left to us in her will is in fact an old master whose sale will make us rich beyond the dreams of avarice. And I’m sure that the fast-growing doubts surrounding Go Set a Watchman (which were well summarized in a Feb. 16 Washington Post story bearing the biting title of “To Shill a Mockingbird”) have pumped up its news value considerably.

But I smell something else in play. I suspect that for all its seeming popularity — as measured by such indexes as museum attendance — there is a continuing and pervasive unease with modern art among the public at large, a sinking feeling that no matter how much time they spend looking, reading or listening, they’ll never quite get the hang of it. As a result, they feel a powerful longing for “new” work by artists of the past.

To be sure, most ordinary folks like at least some modern art, but they gravitate more willingly to traditional fare. Just as “Our Town” (whose form, lest we forget, was ultramodern in 1938) is more popular than “Waiting for Godot,” so, too, are virtually all of our successful “modern” novels essentially traditional in style and subject matter. In some fields, domestic architecture in particular, midcentury modernism is still a source of widespread disquiet, while in others, like classical music and dance, the average audience member does little more than tolerate it.

Terry Teachout, “The lure of ‘new’ old art”, About Last Night, 2015-02-27.

May 26, 2016

Terry Teachout on silent movies

Ten years ago, Terry Teachout finally got around to watching D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, and found (to his relief) that it was just as offensively racist as everyone had always said. He also discovered that silent movies are becoming terra incognita even to those who love old movies:

None of this, however, interested me half so much as the fact that The Birth of a Nation progresses with the slow-motion solemnity of a funeral march. Even the title cards stay on the screen for three times as long as it takes to read them. Five minutes after the film started, I was squirming with impatience, and after another five minutes passed, I decided out of desperation to try an experiment: I cranked the film up to four times its normal playing speed and watched it that way. It was overly brisk in two or three spots, most notably the re-enactment of Lincoln’s assassination (which turned out to be quite effective – it’s the best scene in the whole film). For the most part, though, I found nearly all of The Birth of a Nation to be perfectly intelligible at the faster speed.

Putting aside for a moment the insurmountable problem of its content, it was the agonizingly slow pace of The Birth of a Nation that proved to be the biggest obstacle to my experiencing it as an objet d’art. Even after I sped it up, my mind continued to wander, and one of the things to which it wandered was my similar inability to extract aesthetic pleasure out of medieval art. With a few exceptions, medieval and early Renaissance art and music don’t speak to me. The gap of sensibility is too wide for me to cross. I have a feeling that silent film – not just just The Birth of a Nation, but all of it – is no more accessible to most modern sensibilities. (The only silent movies I can watch with more than merely antiquarian interest are the comedies of Buster Keaton.) Nor do I think the problem is solely, or even primarily, that it’s silent: I have no problem with plotless dance, for instance. It’s that silent film “speaks” to me in an alien tongue, one I can only master in an intellectual way. That’s not good enough for me when it comes to art, whose immediate appeal is not intellectual but visceral (though the intellect naturally enters into it).

As for The Birth of a Nation, I’m glad I saw it once. My card is now officially punched. On the other hand, I can’t imagine voluntarily seeing it again, any more than I’d attend the premiere of an opera by Philip Glass other than at gunpoint. It is the quintessential example of a work of art that has fulfilled its historical purpose and can now be put aside permanently – and I don’t give a damn about history, at least not in my capacity as an aesthete. I care only for the validity of the immediate experience.

[…] Thrill me and all is forgiven. Bore me and you’ve lost me. That’s why I think it’s now safe to file and forget The Birth of a Nation. Yes, it’s still historically significant, and yes, it tells us something important about the way we once were. But it’s boring — and thank God for that.

April 21, 2016

QotD: The amazing (ancient) Greeks

I discovered the Greeks when I was eight, and I came across a copy of Roger Lancelyn-Green’s retelling of The Iliad. I was smitten at once. There was something so wonderfully grand, yet exotic, about the stories. I didn’t get very far with it, but I found a copy of Teach Yourself Greek in the local library and spent weeks puzzling over it. Over the next few years, I read my way through the whole of Greek and Roman mythology, and was drawn into the history of the whole ancient world.

When I was twelve, my classical leanings took me in a new, if wholly predictable, direction. The sexual revolution of the 70s hardly touched most South London schoolboys. The one sex education lesson I had was a joke. Porn was whatever I could see without my glasses in the swimming pool. So I taught myself Latin well enough to read the untranslated naughty bits in the Loeb editions of the classics. The librarians in Lewisham were very particular in those days about what they allowed on their shelves. They never questioned the prestige of the classics, or thought about what I was getting them to order in from other libraries. With help from Martial and Suetonius and Ausonius, among others, I’d soon worked out the mechanics of all penetrative sex, and flagellation and depilation and erotic dances; and I had a large enough fund of anecdotes and whole stories to keep my imagination at full burn all though puberty.

Then, as I grew older, I realised something else about the Greeks — something I’d always known without putting it into words. There’s no doubt that European civilisation, at least since the Renaissance, has outclassed every other. No one ever gathered facts like we do. No one reasoned from them more profoundly or with greater focus. No one approached us in exposing the forces of nature, and in turning them to human advantage. We are now four or five centuries into a curve of progress that keeps turning more steeply upwards. Yet our first steps were guided by others — the Greek, the Romans, the Arabs, and so forth. If we see further than they do, we stand on the backs of giants.

The Greeks had no one to guide them. Unless you want to make exaggerated claims about the Egyptians and Phoenicians, they began from nothing. Between about 600 and 300 BC, the Greeks of Athens and some of the cities of what is now the Turkish coast were easily the most remarkable people who ever lived. They gave us virtually all our philosophy, and the foundation of all our sciences. Their historians were the finest. Their poetry was second only to that of Homer — and it was they who put together all that we have of Homer. They gave us ideals of beauty, the fading of which has always been a warning sign of decadence; and they gave us the technical means of recording that beauty. Again, they had no examples to imitate. They did everything entirely by themselves. In a world that had always been at the midnight point of barbarism and superstition, they went off like a flashbulb; and everything good in our own world is part of their afterglow. Every renaissance and enlightenment we have had since then has begun with a rediscovery of the ancient Greeks. Modern chauvinists may argue whether England or France or Germany has given more to the world. In truth, none of us is fit to kiss the dust on which the ancient Greeks walked.

How can you stumble into their world, and not eventually be astonished by what the Greeks achieved? From the time I was eight, into early manhood, I felt wave after wave of adoration wash over me, each one more powerful than the last.

Richard Blake, “Interview with Richard Blake”, 2014-03-14.

March 2, 2016

QotD: Pictures of Mohammed

While some Muslims were outraged by a magazine printing cartoon pictures of Muhammad, we have to step back and calmly ask, are pictures of Muhammad really forbidden in Islam? – the answer might surprise you.

Numerous passages in the Qur’an prohibit idolatry, and worshipping statues or pictures, but there is not even single verse in the Qur’an that explicitly or implicitly says not to have any pictures of Muhammad. This bears repeating: There is not a single verse in the Qur’an that prohibits making or having pictures of Muhammad or people or animals or trees. In fact, there are some verses in the Qur’an which mention images in a positive context and which therefore presuppose that some statues or images were approved by God, see the article Muhammad and Images.

However, the vast majority of Muslims are Sunni Muslims, who regard six authorized collections of hadiths as the highest written authority in Islam after the Qur’an. The hadiths are records, often very detailed, of what Muhammad taught and did. We give multiple quotations to show that these teachings are not confined to just one writer/collector, but are spread throughout the different hadith collections.

Where multiple trustworthy hadiths agree, Sunni Muslims will take this as binding. In other words, people today are kicked out of Islam, or even killed based on the hadiths.

Pictures of Muhammad are “not exactly” forbidden in the hadiths either. The hadiths do not single out Muhammad’s picture. Rather, in the hadith we find the prohibition of all pictures of people or animals, which would include pictures from a camera.

For example, Sahih Muslim vol.3 no.5268 (p.1160) says, “Ibn ‘Umar reported Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) having said: Those who paint pictures would be punished on the Day of Resurrection and it would be said to them: Breathe soul into what you have created.”

Notice that the prohibition was not just against idolators who made pictures, or even Muslims who made pictures for other reasons, but for anyone who made pictures.

Sahih Muslim vol.3 no.5271 (p.1161) gives a little more detail: “This hadith has been reported on the authority of Abu Mu’awiya though another chain of transmitters (and the words are): ‘Verily the most grievously tormented people amongst the denizens [inhabitants] of Hell on the Day of Resurrection would be the painters of pictures.”

“Narrated ‘Aisha: Allah’s Apostle said, ‘The painter of these pictures will be punished on the Day of Resurrection, and it will be said to them, Make alive what you have created.’” Bukhari vol.9 book 93 no.646 p.487. no.647 p.487 is the same except it is narrated by Ibn ‘Umar.

No pictures of people or animals according to Bukhari vol.4 book 54 no.447-450 p.297-299.

Conclusion: It is clear that the hadiths prohibit pictures of animals or people, especially in homes. There is no focus on pictures of Muhammad per se. All pictures of people and animals are forbidden. It is a completely general prohibition.

February 19, 2016

QotD: Art, taste, and judgment

All of us, if we are not merely children or possessed of childlike tastes, recall works that we had to work to learn to love, such as obtuse poems which has to be explained before they were beautiful, words of archaic or foreign cant, or novels referring to experiences in life we were too young, on first reading, to recognize or know. Even science fiction and fantasy has some introductory learning that needs be done, a certain grasp of the scientific world view or the conventions of fantastic genre that must be gained, before the work is loveable. The only art I know that has no introductory effort at all is comic books, but even they, in recent years, now require introduction, since no one unaware of the decades of continuity can simply pick up a comic book and read it with pleasure: they are written for adults, these days, not kids, and adults expect and are expected to try harder to get into the work before getting something out of it.

The reason why modern art can pass for art is that the Tailors of the Emperor’s New Clothes can claim, and the claim cannot be dismissed unexamined, that modern art merely is has a steeper learning curve than real art. Once you get all the in-jokes and palindromes and Irish and Classical references in James Joyce (so the Tailors say) you can read ULYSSES with the same pleasure that a student, once he learns Latin, reads Virgil. And as long as you are in sympathy with the effort at destruction and deconstruction, this modern art has the same fascination as watching a wrecking crew tear down a fair and delicate antique fane with fretted colonnades and an architrave of flowing figures recalling forgotten wars between giants and gods. What child will not cheer when he sees a wrecking ball crash through the marble and stained glass of old and unwanted beauty? How he will clap when the dynamite goes off, and squeal, and hold his ears! I am not being sarcastic: there is something impressive in such acts.

Let us add a second observation: great novels and great paintings, symphonies, even great comic books, are ones that reward a second rereading or heeding or viewing. A book is something you read once and enjoy and throw away. A good book is one you read twice, and get something out of it a second time. A great book is one that has the power to make you fall in love, and each time you reread it, it is as new and fresh as Springtime, and you see some new nuance in it, the same way you see more beauty each time you see your wife of many years, and will forever, no matter how many years you see her face. (Those of you who are not in love, or not happily married, or who have never read a truly great book, will not know whereof I speak. Alas, I cannot describe the colors of a sunrise to a man born blind.)

Let us assume that there is no beauty in art, no objective rules. If that were so, how do we explain the two observations noted above, first, that some art must be learned before it is loved, and second, that some art rewards additional scrutiny indefinitely, a fountainhead that never runs dry. The explanation that the learning is not learning but merely acclamation, an Eskimo learning to tolerate the tropics, a Bushman growing to enjoy the snow, would make sense if and only if any art or rubbish would reward equal study with equal pleasure.

If the pleasure I get out of a work of art I had to grow and learn to like was merely due to me and my tastes, and the learning was not learning at all, but merely an adjustment of taste from one arbitrary genre convention to another, then the outcome or result could not differ from artwork to artwork, as long as I were the same.

If I can see more rich detail each time I reread Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, and if indeed there are beauties that pierce like swords, and if this were due to me and only to me, and not due to something in the work, I should be able to study a pile of rocks besmirched with stains of oil and offal in a rubble heap, and with the same passage of time and effort, force myself to see equal beauty within.

But I cannot, nor can any man. Therefore the sublime is not just in me the observer; logically, it must be in the thing observed. There must be something really there.

If this argument satisfies, it tells us, with the clarity of a Deist argument, that there is an objective beauty in the world, but not what it is.

As in theological argument, in aesthetics we can only know more of the beauty of the universe if it comes to us in the artistic equivalent of revelation. We have to look at beauty in nature and see what is there, and what its rules are, before we look at beauty in human handiwork.

John C. Wright, “Supermanity and Dehumanity (Complete)”, John C. Wright’s Journal, 2014-12-13.

January 30, 2016

QotD: Government funding for the arts

People who oppose Soviet-style collective farms, government subsidies to agriculture, or public ownership of grocery stores because they want the provision of food to be a private matter in the marketplace are generally not dismissed as uncivilized or uncaring. Hardly anyone would claim that one who holds such views is opposed to breakfast, lunch, and dinner. But people who oppose government funding of the arts are frequently accused of being heartless or uncultured. What follows is an adaptation of a letter I once wrote to a noted arts administrator who accused me of those very things. It articulates the case that art, like food, should rely on private, voluntary provision.

Thanks for sending me your thoughts lamenting cuts in arts funding by state and federal governments. In my mind, however, the fact that the arts are wildly buffeted by political winds is actually a powerful case against government funding. I’ve always believed that art is too important to depend on politics, too critical to be undermined by politicization. Furthermore, expecting government to pay the bill for it is a cop-out, a serious erosion of personal responsibility and respect for private property.Those “studies” that purport to show X return on Y amount of government investment in the arts are generally a laughingstock among economists. The numbers are often cooked and are almost never put alongside competing uses of public money for comparison. Moreover, a purely dollars-and-cents return — even if accurate — is a small part of the total picture.

The fact is, virtually every interest group with a claim on the treasury argues that spending for its projects produces some magical “multiplier” effect. Routing other people’s money through the government alchemy machine is supposed to somehow magnify national wealth and income, while leaving it in the pockets of those who earned it is somehow a drag. Assuming for a moment that such preposterous claims are correct, wouldn’t it make sense from a purely material perspective to calculate the “average” multiplier and then route all income through the government? Don’t they do something like that in Cuba and North Korea? What happened to the multiplier in those places? It looks to me that somewhere along the way it became a divisor.

Lawrence W. Reed, “#34 – ‘Government Must Subsidize the Arts'”, The Freeman, 2014-12-05.

January 19, 2016

Inventing the English countryside

Matt Ridley on the legacy of Capability Brown:

Next year marks the 300th birthday of Lancelot Brown at Kirkharle, in Northumberland, the man who saw “capability” in every landscape and indefatigably transformed England. In his 280 commissions, Capability Brown stamped his mark on some 120,000 acres, tearing out walls, canals, avenues, topiary and terraces to bring open parkland, with grassy tree-topped hills and glimpses of sinuous, serpentine lakes, right up to the ha-has of country houses.

Brown was not the first to design informal and semi-naturalistic landscapes: he followed Charles Bridgeman and William Kent. But he was by far the most prolific and influential. His is a type of landscape that is now imitated in parks all round the world, from Dubai to Sydney to Europe: it’s known as “jardin anglais” and was admired by Catherine the Great and Thomas Jefferson.

Frederick Law Olmsted laid out Central Park in New York in conscious emulation of Brown — as John Nash did with St James’s Park (Hyde Park is by Bridgeman). Golf courses nearly always pay unconscious homage to Brown. There is something deeply pleasing about a view of rolling grassland punctuated with clumps of low-branching trees and glimpses of distant water.

Mountains may have more majesty, forests more fear, deserts more danger, townscapes more detail, fields more fruitfulness, formal gardens more symmetry — but it is the informal English parkland of Capability Brown that you would choose for a picnic, or for a visit with a potential lover. It feels natural.

And yet of course it is wholly contrived. One of Tom Stoppard’s characters explains to another in his play Arcadia, as they contemplate the view of a park from a country house:

BERNARD: Lovely. The real England.

HANNAH: You can stop being silly now, Bernard. English landscape was invented by gardeners imitating foreign painters who were evoking classical authors. The whole thing was brought home in the luggage from the grand tour. Here, look — Capability Brown doing Claude, who was doing Virgil. Arcadia!

Hannah’s right. Claude Lorrain’s paintings of scenes from Virgil were all the rage in the 1730s. By the 1740s, when Brown started work at Stowe under William Kent, prints of 44 of Claude’s landscapes were on sale in London. The landscape at Stourhead (not by Brown), with its Grecian temples seen across lakes, is little more than a copy of Claude’s Aeneas at Delos. Kent’s genius, inspired by Lord Burlington and Alexander Pope, was to supply this craving for classical rural Arcadia.

[…]

The satirist Richard Cambridge joked that he wanted to die before Capability Brown so that he could see heaven before it was “improved”. In 2016 — the date of Brown’s birth is unknown; we have only the date of his baptism, August 30 — I shall raise a glass to a humbly born county boy, who mixed Northumberland with the Serengeti to produce Arcadia and gave us the archetypical English landscape.

December 18, 2015

“The gift economy of the digital world is a mirage”

Grant McCracken responds to Clay Shirky’s “gift economy” notions:

In point of fact, the internet as a gift economy is an illusion. This domain is not funding itself. It is smuggling in the resources that sustain it, and to the extent that Shirky’s account helps conceal this market economy, he’s a smuggler too. This world cannot sustain itself without subventions. And to this extent it’s a lie.

Shirky insists that generalized reciprocity is the preferred modality. But is it?

[In the world of fan fic, there] is a “two worlds” view of creative acts. The world of money, where [established author, J.K.] Rowling lives, is the one where creators are paid for their work. Fan fiction authors by definition do not inhabit this world, and more important, they rarely aspire to inhabit it. Instead, they often choose to work in the world of affection, where the goal is to be recognized by others for doing something creative within a particular fictional universe. (p. 92)

Good and all, but, again, not quite of this world. A very bad situation, one that punishes creators and our culture, is held up as somehow exemplary. But of course reputation economies spring up, but we don’t have to choose. We can have both market and reputation economies. But it’s wrong surely, to make the latter a substitute for the former.

Shirky appears to be persuaded that it’s “ok” for creators to create without material reward. But I think it’s probably true that they are making the best of a bad situation. Recently, I was doing an interview with a young respondent. We were talking about her blog, a wonderful combination of imagination and mischief. I asked her if she was paid for this work and she said she was not. “Do you think you should be paid?” I asked.

She looked at me for a second to make sure I was serious about the question, thought for a moment and then, in a low voice and in a measured somewhat insistent way, said, “Yes, I think I should be paid.” There was something about her tone of voice that said, “Payment is what is supposed to happen when you do work as good as mine.”

[…]

Finally, I do not mean to be unpleasant or to indulge ad hominem attack, but I think there is something troubling about a man supported by academic salary, book sales, and speaking engagements telling Millennials how very fine it is that they occupy a gift economy which pays them, usually, nothing at all. I don’t say that Shirky has championed this inequity. But I don’t think it’s wrong to ask him to acknowledge it and to grapple with its implications.

The gift economy of the digital world is a mirage. It looks like a world of plenty. It is said to be a world of generosity. But on finer examination we discover results that are uneven and stunted. Worse, we discover a world where the good work goes without reward. The more gifted producers are denied the resources that would make them still better producers and our culture richer still.

What would people, mostly Millennials, do with small amounts of capital? What enterprises, what innovations would arise? How much culture would be created? I leave for another post the question of how we could install a market economy (or a tipping system) online. And I have to say I find it a little strange we don’t have one already. Surely the next (or the present) Jack Dorsey could invent this system. Surely some brands could treat this as a chance to endear themselves to content creators. Surely, there is an opportunity for Google. If it wants to save itself from the “big business” status now approaching like a freight train, the choice is clear. Create a system that allows us to reward the extraordinary efforts of people now producing some of the best artifacts in contemporary culture.

December 12, 2015

The cargo cult of modern art

Richard Bledsoe on the similarities between the cargo cults of Pacific Islanders during and after the Second World War and the modern art scene:

Much of establishment contemporary art has become an inverted cargo cult.

The phenomenon of the cargo cult originally was observed when the primitive tribal societies of the South Pacific encountered the advanced cultures of the West. It reached a pitch of religious fervor after World War II.

The industrial manufactured items of the newcomers amazed the remote villagers of islands like New Guinea and Tanna. The strangers from over the sea brought with them riches in the form of machines and goods — airplanes, tools, medicines, canned food, radios and the like — made from materials incomprehensible to what were practically Stone Age people. The tribes decided surely such wonderful items must be made by the gods.

As battles raged in the Pacific, the indigenous populations observed the soldiers at work: marching around in uniforms, clearing runways, talking on radios. In response the planes arrived, seemingly from heaven, bringing to the islands the massive quantities of materials needed for the war effort. To the natives who got to share some of the magical items, this treasure — the technological output of developed nations — came to be referred to collectively by the pidgin word cargo.

But when the war ended, the soldiers left. The flow of magic cargo ceased. The tribesmen had lost access to the gifts from the gods.

The abandoned natives developed a plan to get back into divine favor. Having no frame of reference for the ways of the modern world, they interpreted the activities of construction and communications the visitors performed as forms of ritual. The tribesmen would reenact the rites they had seen the foreigners perform, recreate their ceremonial objects. This would please the gods, who would start delivering the cargo again — but this time, to the natives.

The islanders designed outfits based on military uniforms. They drilled in cadence, carrying rifles of bamboo. They built wooden aerials, constructed mock radios, clearing landing strips in the jungle, placed decoy planes of straw on them. And waited.

[…]

To our rational minds this is preposterous. We understand the uselessness of evoking the facade of a machine without the necessary functionalities being incorporated into it. What matters is the inner workings, not the appearance.

And yet, a form of this magical thinking has infected contemporary art. The subservience of art to political issues derails the purpose of the artist. The prevalent dogma interferes with the discovery of a personal artistic vision. So contemporary artists attempt to imitate their way into a valid artistic experience.

In a stunning reversal, in our advanced technological society, artists uncomprehendingly recreate inferior approximations, parodying the objects and gestures of the past and the primitive, trying in vain to summon the sense of awe and wholeness present in the art of bygone ages. By mimicking and mocking the outer forms of the originators, the artists hope the gods will arrive bearing their eternal gifts — that these snotty knock offs will also rise to the level of art.