Lindybeige

Published on 28 Nov 2018The Maya built many cities that even now are reappearing from the jungles of Central America. The first video of many in a series.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

I was not paid to make this video, but INGUAT paid for my flights, accommodation, and activities.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

November 29, 2018

El Zotz – Lost City of the Bats

November 20, 2018

QotD: Why do we drink?

Alcoholic beverages, like agriculture, were invented independently many different times, likely on every continent save Antarctica. Over the millennia nearly every plant with some sugar or starch has been pressed into service for fermentation: agave and apples, birch tree sap and bananas, cocoa and cassavas, corn and cacti, molle berries, rice, sweet potatoes, peach palms, pineapples, pumpkins, persimmons, and wild grapes. As if to prove that the desire for alcohol knows no bounds, the nomads of Central Asia make up for the lack of fruit and grain on their steppes by fermenting horse milk. The result, koumiss, is a tangy drink with the alcohol content of a weak beer.

Alcohol may afford psychic pleasures and spiritual insight, but that’s not enough to explain its universality in the ancient world. People drank the stuff for the same reason primates ate fermented fruit: because it was good for them. Yeasts produce ethanol as a form of chemical warfare — it’s toxic to other microbes that compete with them for sugar inside a fruit. That antimicrobial effect benefits the drinker. It explains why beer, wine, and other fermented beverages were, at least until the rise of modern sanitation, often healthier to drink than water.

What’s more, in fermenting sugar, yeasts make more than ethanol. They produce all kinds of nutrients, including such B vitamins as folic acid, niacin, thiamine, and riboflavin. Those nutrients would have been more present in ancient brews than in our modern filtered and pasteurized varieties. In the ancient Near East at least, beer was a sort of enriched liquid bread, providing calories, hydration, and essential vitamins.

[…]

Indirectly, we may have the nutritional benefits of beer to thank for the invention of writing, and some of the world’s earliest cities — for the dawn of history, in other words. Adelheid Otto, an archaeologist at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich who co-directs excavations at Tall Bazi, thinks the nutrients that fermenting added to early grain made Mesopotamian civilization viable, providing basic vitamins missing from what was otherwise a depressingly bad diet. “They had bread and barley porridge, plus maybe some meat at feasts. Nutrition was very bad,” she says. “But as soon as you have beer, you have everything you need to develop really well. I’m convinced this is why the first high culture arose in the Near East.”

Andrew Curry, “Our 9,000-Year Love Affair With Booze”, National Geographic, 2017-02.

October 20, 2018

Cavalry was a stupid idea

Lindybeige

Published on 28 Aug 2016The Great Courses Plus free trial: http://ow.ly/fA12302OFSt

Riding a horse into battle is not a technique easy to adopt. The first man to suggest it may have been laughed at.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

A long ramble by me. Possibly I should have done one video about Celtic/Roman four-pommelled saddles, and a separate one about how cavalry took a long time to develop.

I wasn’t quite at my peak while making this one. I came back from abroad with a virus, and had spent the previous day coughing.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

September 25, 2018

Amazons – fierce fighting tribe or just ancient Greek porn?

Lindybeige

Published on 21 Jun 2011You can believe in them if you want, but if you do, you should out of fairness to other mythological characters believe in giants, cyclopes, griffins, and gorgons.

August 30, 2018

August 25, 2018

Mediterranean trade in the Iron Age

Jan Bakker, Stephan Maurer, Jörn-Steffen Pischke, and Ferdinand Rauch look at the relationships between trade and economic growth around the Mediterranean during the Iron Age:

Economists often point out the benefits of trade, yet empirical evidence for these benefits has been hard to come by and tends to be recent. This column goes back to the first millennium BC to analyse the growth effects of one of the first major trade expansions in human history: the systematic crossing of the open sea in the Mediterranean by the Phoenicians. A strong positive relationship between connectedness and archaeological sites suggests a large role for geography and trade in development even at such an early juncture in history.

The effects of free trade inspire a lot of public debate these days, and policies to restrict trade are gaining in prominence. Economists since Adam Smith and David Ricardo have typically pointed out the benefits of trade. Yet empirical evidence for these benefits has been much harder to come by and is much more recent. In particular, empirical economists have tried to demonstrate that more open economies or more integrated markets see faster growth. The relationship between these two variables is not much disputed; the more difficult question is whether this is due to trade causing growth or richer economies being more open.

[…]

To analyse whether this increased trade also caused growth, we exploit the fact that open sea sailing creates different levels of connectedness for different points on the coast. The shape of the coast and the location of islands determineshow easy it is to reach other points, which might be potential trading partners, within a certain distance. We create such a measure of connectedness for travel via sea. Figure 1 shows the values of this measure on a map and demonstrates how some regions, for example the Aegean but also southern Italy and Sicily, are much better connected than others.

We use this measure of connectedness as a proxy for trading opportunities.

Note: Darker blue indicates better connected locations.

Measuring growth for an early period of human history is more difficult as we have no standard measure of income, GDP, or even population. We quantify growth by the presence of archaeologic sites for settlements or urbanisations. While this is clearly not a perfect measure, more sites should imply more human presence and activity. We then relate the number of active archaeological sites in a particular period to our measure of connectedness.

We find a large positive relationship between connectedness and archaeological sites. The effect of connections on growth in the Iron Age Mediterranean are up to twice as large as the effects Donaldson and Hornbeck (2016) found for US railroads. Although these results are unlikely to be directly comparable, the magnitudes suggest a large role for geography and trade in development even at such an early juncture in history.

July 28, 2018

Historical vandalism at Stonehenge

Jocelyn Sears on the barbaric “souvenir” habits of 18th century English “tourists”:

In 1860, a concerned tourist wrote to the London Times decrying the “foolish, vulgar and ruthless practice of the majority of visitors” to Stonehenge “of breaking off portions of it as keepsakes.” Today, taking a hammer and chisel to a Neolithic monument seems like obvious vandalism, but during the Victorian era, such behavior was not only common but expected.

English antiquarian tourists, who were mostly upper class, had developed the habit of taking makeshift relics from the historical sites they visited during the 18th century. By 1830, the practice was so widespread that the English painter Benjamin Robert Haydon dubbed it “the English disease,” writing, “On every English chimney piece, you will see a bit of the real Pyramids, a bit of Stonehenge! […] You can’t admit the English into your gardens but they will strip your trees, cut their names on your statues, eat your fruit, & stuff their pockets with bits for their musaeums.”

For centuries, both locals and visitors had taken pieces of Stonehenge for use in folk remedies. As early as the 12th century, rumors of the stones’ healing properties appear in the writing of Geoffrey of Monmouth, and in 1707, Reverend James Brome wrote that their scrapings were still thought to “heal any green Wound, or old Sore.” In the 1660s, the English antiquarian John Aubrey reported a local superstition that “pieces or powder of these stones, putt into their wells, doe drive away the Toades.”

Eventually, tourists were not just taking from Stonehenge, but also leaving their mark, too. By the middle of the 17th century, tourist graffiti was appearing on the stones. The name of Johannes Ludovicus de Ferre — abbreviated “IOH : LVD : DEFERRE” — is etched, and so is the engraving “I WREN,” which may refer to Christopher Wren, the famed architect who designed St. Paul’s Cathedral.

As early as 1740, the archaeologist William Stukeley was decrying “the unaccountable folly of mankind in breaking pieces off [the stones] with great hammers,” and by the end of the 19th century, according an 1886 commenter, “Almost every day takes some fragment from the ruins, or adds something to the network of scrawling with which the surface of the stone is defaced.”

July 19, 2018

Mucking around with Stonehenge

Many people are still under the impression that Stonehenge was built by the Druids (debunked in this video by Siobhan Thompson). At least as many people think that the modern day stone circle is an undisturbed historical relic, and that the stones are standing today as and where they have for thousands of years. All the way back in 2001, Emma Young did a quick debunking of that theory in New Scientist:

Most of the one million visitors who visit Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain every year believe they are looking at untouched 4,000-year-old remains. But virtually every stone was re-erected, straightened or embedded in concrete between 1901 and 1964, says a British doctoral student.

“What we have been looking at is a 20th-century landscape, reminiscent of what Stonehenge might have looked like thousands of years ago,” says Brian Edwards, a student at the University of the West of England in Bristol.

Stonehenge isn’t the only ancient site to have been transformed in recent years, he says. “Even many of the local people in Avebury weren’t aware that a lot of the stones were put up in the 1930s,” he told New Scientist.

[…]

English Heritage says it is now considering covering the Stonehenge alteration programme in detail in the next edition of its official guidebook to the site. A decision not to include the work in official guides was taken in the 1960s, says Dave Batchelor, English Heritage’s senior archaeologist.

The first restoration project took place in 1901. A leaning stone was straightened and set in concrete, to prevent it falling.

More drastic renovations were carried out in the 1920s. Under the direction of Colonel William Hawley, a member of the Stonehenge Society, six stones were moved and re-erected.

Cranes were used to reposition three more stones in 1958. One giant fallen lintel, or cross stone, was replaced. Then in 1964, four stones were repositioned to prevent them falling.

The 1920s ‘restoration’ was the most “vigorous”, says Christopher Chippindale of the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. “The work in the 1920s under Colonel William Crawley is a sad story,” he says.

As I commented on a post back in 2010:

I imagine, given how many times Stonehenge has been mucked about with by earlier enthusiasts, there must be much misleading data has to be sifted and re-sifted before any definite discoveries can be announced. Stonehenge has been fascinating people for centuries and there are probably lots of amateur investigations that may well have made the situation more confusing (think of a sixteenth century equivalent of Indiana Jones or Lara Croft with a nose for treasure).

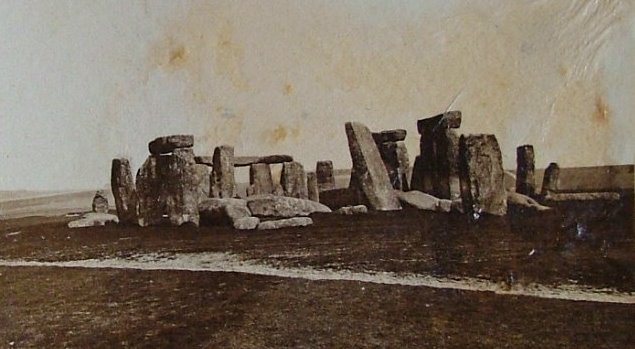

Atlas Obscura recently had a set of photos of Stonehenge taken in 1867 likely featuring the family of Colonel Sir Henry James, of the Ordnance Survey. There’s also a watercolour by John Constable from around 1835 showing a very different, more ruin-y monument:

May 29, 2018

ESR’s thumbnail sketch on the origins of the Indo-European language families

When you mash historical linguistics hard enough into paleogenetics, interesting things fall out:

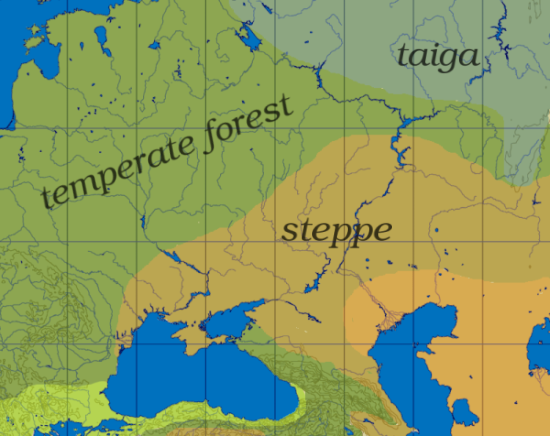

The steppe extends roughly from the Dniepr to the Ural or 30° to 55° east longitude, and from the Black Sea and the Caucasus in the south to the temperate forest and taiga in the north, or 45° to 55° north latitude.

Via Wikipedia

What we can now say pretty much for sure: Proto-Indo-European was first spoken on the Pontic Steppes around 4000 BCE. That’s the grasslands north of the Black Sea and west of the Urals; today, it’s the Ukraine and parts of European Russia. The original PIE speakers (which we can now confidently identify with what archaeologists call the Yamnaya culture) were the first humans to domesticate horses.

And – well, basically, they were the first and most successful horse barbarians. They invaded Europe via the Danube Valley and contributed about half the genetic ancestry of modern Europeans – a bit more in the north, where they almost wiped out the indigenes; a bit less in the south where they mixed more with a population of farmers who had previously migrated in on foot from somewhere in Anatolia.

The broad outline isn’t a new idea. 400 years ago the very first speculations about a possible IE root language fingered the Scythians, Pontic-Steppe descendants in historical times of the original PIE speakers – with a similar horse-barbarian lifestyle. It was actually a remarkably good guess, considering. The first version of the “modern” steppe-origin hypothesis – warlike bronze-age PIE speakers domesticate the horse and overrun Europe at sword- and spear-point – goes back to 1926.

But since then various flavors of nationalist and nutty racial theorist have tried to relocate the PIE urheimat all over the map – usually in the nut’s home country. The Nazis wanted to believe it was somewhere in their Greater Germany, of course. There’s still a crew of fringe scientists trying to pin it to northern India, but the paleogenetic evidence craps all over that theory (as Cochran explains rather gleefully – he does enjoy calling bullshit on bullshit).

Then there have been the non-nutty proposals. There was a scientist named Colin Renfrew who for many years (quite respectably) pushed the theory that IE speakers walked into Europe from Anatolia along with farming technology, instead of riding in off the steppes brandishing weapons like some tribe in a Robert E. Howard novel.

Alas, Renfrew was wrong. It now looks like there was such a migration, but those people spoke a non-IE language (most likely something archaically Semitic) and got overrun by the PIE speakers riding in a few thousand years later. Cochran calls these people “EEF” (Eastern European Farmers) and they’re most of the non-IE half of modern European ancestry. Basque is the only living language that survives from EEF times; Otzi the Iceman was EEF, and you can still find people with genes a lot like his in the remotest hills of Sardinia.

Even David Anthony, good as he is about much else, seems rather embarrassed and denialist about the fire-and-sword stuff. Late in his book he spins a lot of hopeful guff about IE speakers expanding up the Danube peacefully by recruiting the locals into their culture.

Um, nope. The genetic evidence is merciless (though, to be fair, Anthony can’t have known this). There’s a particular pattern of Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA variation that you only get in descendant population C when it’s a mix produced because aggressor population A killed most or all of population B’s men and took their women. Modern Europeans (C) have that pattern, the maternal line stuff (B) is EEF, and the paternal-line stuff (A) is straight outta steppe-land; the Yamnaya invaders were not gentle.

How un-gentle were they? Well…this paragraph is me filling in from some sources that aren’t Anthony or Cochran, now. While Europeans still have EEF genes, almost nothing of EEF culture survived in later Europe beyond the plants they domesticated, the names of some rivers, and (possibly) a murky substratum in some European mythologies.

The PIE speakers themselves seem to have formed, genetically, when an earlier population called the Ancient Northern Eurasians did a fire-and-sword number (on foot, that time) on a group of early farmers from the Fertile Crescent. Cochrane sometimes calls the ANEs “Hyperboreans” or “Cimmerians”, which is pretty funny if you’ve read your Howard.

May 28, 2018

Middle East: Palmyra Today – Afterword – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 31 Oct 2015Learn about Odenathus, King of Palmyra: http://bit.ly/1GDsDvz

____________Palmyra is an embodiment of our shared past, but right now it’s under the control of ISIS. They have destroyed the antiquities that remind us of our shared past. We would like to take a moment to honor Dr. Khaled al-Assad, the museum director who gave his life rather than reveal the locations of more Palmyrene relics for ISIS to destroy.

May 13, 2018

QotD: The lost works of Epicurus

[Most of the original writings of Epicurus have been lost.] There are the elaborate refutations of Epicureanism by Cicero and Plutarch. These inevitably outline and sometimes even quote what they are attacking. There are hundreds of other references to Epicurus in the surviving literature of the ancient world. Some of these are useful sources of information. Some are our only sources of information on certain points of the philosophy.

During the past few centuries, scholars have been trying to read the charred papyrus rolls from a library in Herculaneum buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. Some of these contain works by Philodemus of Gadara, an Epicurean philosopher of the 1st century BC. Much of this library remains unexcavated, and most of the rolls recovered have not really been examined. There are hopes that a complete work by Epicurus will one day be found here.

Above all else, though, is the De Rerum Natura of Lucretius. He was a Roman poet who died around the year 70 BC. His epic, in which he claims to restate the physical doctrines of Epicurus, was unfinished at the time of his death, and it is believed that Cicero himself edited the six completed books and published the text roughly as it has come down to us. This is one of the greatest poems ever written, and perhaps the strangest of all the great poems. It is also the longest explanation in a friendly source of the physical theories of Epicurus.

Therefore, if anyone tries to say in any detail what Epicurus believed, he will not be arguing from strong authority. If we compare the writings of any extant philosopher with the summaries and commentaries, we can see selective readings and exaggerations and plain misunderstandings. How much of what Karl Marx really said can be reliably known from the Marxist and anti-Marxist scholars of the 20th century? Even David Hume, who wrote very clearly in a very clear language, seems to have been consistently misunderstood by his 19th century critics. For Epicurus, we may have reliable information about the main points of his ethics and his physics. We have almost no discussions of his epistemology or his philosophy of mind. Anyone who tries writing on these is largely guessing.

All this being said, enough has survived to make a general account of the philosophy possible. Epicurus appears to have been a consistent thinker. Though it may only ever be a guess — unless the archaeologists in Herculaneum find the literary equivalent of Tutankhamen’s tomb — we can with some confidence proceed from what Epicurus did say to what he might have said. Certainly, we can give a general account of the philosophy.

Sean Gabb, “Epicurus: Father of the Enlightenment”, speaking to the 6/20 Club in London, 2007-09-06.

April 4, 2018

3,200 Year Old Stone May FINALLY Solve SEA PEOPLE Mystery

Beyond Science

Published on 12 Oct 2017Was it solved?

April 2, 2018

Vikings – did they actually exist?

Lindybeige

Published on 9 Oct 2015The term ‘Viking’ is used inaccurately most of the time. Scandinavia was home to many Norse-speaking farmers, fishermen, carpenters, and cheese-makers, who spent between none and very little of their time carrying out sea raids.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

The Five Forms of Ancient Egyptian Writing!

The Study of Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Published on 12 Mar 2018In this brief video I discuss the five different forms of writing in Ancient Egypt!

March 21, 2018

Playing with Pleasure l HISTORY OF SEX TOYS

IT’S HISTORY

Published on 19 Sep 2015Erotic sex toys like dildos are no modern day invention. Thousands of years ago, stone phalli already served their purposes contributing to lust and passion. Throughout history more inventions like the vibrator have been developed to improve catering to our desire. Although love toys have been around for more than 20.000 years, society and religions have been struggling with their acceptance. Almost as long as they have existed.