an audience of any size has yet to be found

So far so CBC, then.

I’m not sure how to describe the CBC to American viewers. The BBC routinely produces content that’s quite entertaining (deliberately, I mean) so it’s not a good analogy. I suppose the best analog would be if NPR and PBS merged and were run by the CPUSA with $20 billion dollars of taxpayer money, and still managed to produce nothing anyone wanted to watch.

Daniel Ream, commenting on David Thompson, “The Giant Testicles Told Me”, DavidThompson, 2022-10-10.

January 12, 2023

QotD: Describing the CBC to Americans

January 11, 2023

“The PM and the public safety minister were lying to the public. That should matter.”

The editors of The Line regretfully return from holidays to start a new year, and the federal government’s gun confiscation bill (not called that, of course) gets both barrels:

The first item worth mentioning: remember how back in November and December the prime minister and the public safety minister, Messrs. Trudeau and Mendicino, were dismissing any suggestion that they were banning hunting rifles as hype? Or Conservation misinformation? When they were saying that the suggestions were false, and those making them were sowing confusion?

Well! Funny thing happened over the break. The PM, in his year-end interviews, is now admitting that the suggestions were, in fact, right.

Take this, for example, from his sit down with CTV News (our emphasis added):

“Our focus now is on saying okay, there are some guns, yes, that we’re going to have to take away from people who were using them to hunt,” Trudeau said. “But, we’re going to also make sure that you’re able to buy other guns from a long list of guns that are accepted that are fine for hunting, whether it’s rifles or shotguns. We’re not going at the right to hunt in this country. We are going at some of the guns used to do it that are too dangerous in other contexts.”

We’ll skip much analysis here. We think this is dumb policy, and we’ve explained why before, but it’s at least an acknowledgement of what their policy actually is, and very obviously was since the very time it was announced back in November. There’s no room for any confusion or doubt here. The Liberals spent weeks crying LIES! and MISINFORMATION! at people who were accurately describing what they were doing.

You can support the policy being proposed — again, we don’t, but that’s fine — but you can’t excuse this. The PM and the public safety minister were lying to the public. That should matter.

We’ll have more to say on this later. But for now, that’s the update: The Liberals now admit they’re trying to do the dumb thing they spent weeks insisting they weren’t doing.

This is, incredibly, a kind of progress.

Related somewhat to the above: a smart friend of The Line, who cannot be named as this stuff is their day job, told us weeks ago to watch for a schism in the NDP over this issue. For the Liberals, their dumb policy proposal still makes political sense. Well, it probably does — we have some suspicion that the LPC has maxed out the electoral utility of hammering on guns, and may now face more blowback than benefit, but time will tell. Still, the proposal may make sense for the Liberals: they are utterly dependent on urban and suburban women to survive, and the dumb gun proposal apparently resonates with them. And that’s true for part of the NDP’s base, too, but, critically, our friend reminded us, not for all of it.

The federal NDP of today is a strange creature. It’s partly very much a party of the deepest, wokest downtown ridings, but there’s also a big contingent of Dipper MPs from places like northern Ontario and rural parts of Manitoba and British Columbia. Cracking down on guns just plays differently there. When the policy was first announced, this division among NDP MPs didn’t take long to come into public view. Jagmeet Singh, himself very much of the NDP’s woke urban contingent, was quiet for a few days before very clearly and obviously pivoting to oppose the proposed expansion of the banned firearms. The Liberals can afford to write off their last remaining rural, non-urban MPs. The NDP simply can’t.

And, our friend told us — again, this was weeks ago, right at the outset — if Singh didn’t get the message pronto, the party would fracture over this … and that Wab Kinew, leader of the Manitoba NDP, would be the leader of the rebels.

We aren’t experts on Kinew, or in internal NDP power dynamics, so we simply thanked our friend for the tip and analysis, and assured them we’d keep an eye on it. And we did.

And wouldja look at that.

Interesting, eh?

Anyway. As of now the Liberals are still talking tough on the amendment. But they need at least one party to work with them to push it forward. We can’t say for sure, but we wonder if the Liberals are comfortable talking tough about it because they now accept they can’t push it forward — at least not any time soon. The Bloc seems wary of getting saddled with this and the NDP, indeed, might split over this issue if Singh were to try.

So we’ll keep watching this, and particularly Mr. Kinew, who may indeed covet Mr. Singh’s job.

To our friend: you were right. Thanks for the tip.

Al Capone’s Soup Kitchen

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 10 Jan 2023

(more…)

“[T]o the ordinary American, those values [diversity, equity, and inclusion] sound virtuous and unobjectionable”

John Sailer writes in The Free Press on the rapid rise of the “diversity, equity, and inclusion” bureaucracy in American higher education:

The principles commonly known as “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) are meant to sound like a promise to provide welcome and opportunity to all on campus. And to the ordinary American, those values sound virtuous and unobjectionable.

But many working in academia increasingly understand that they instead imply a set of controversial political and social views. And that in order to advance in their careers, they must demonstrate fealty to vague and ever-expanding DEI demands and to the people who enforce them. Failing to comply, or expressing doubt or concern, means risking career ruin.

In a short time, DEI imperatives have spawned a growing bureaucracy that holds enormous power within universities. The ranks of DEI vice presidents, deans, and officers are ever-growing — Princeton has more than 70 administrators devoted to DEI; Ohio State has 132. They now take part in dictating things like hiring, promotion, tenure, and research funding.

More significantly, the concepts of DEI have become guiding principles in higher education, valued as equal to or even more important than the basic function of the university: the rigorous pursuit of truth. Summarizing its hiring practices, for example, UC Berkeley’s College of Engineering declared that “excellence in advancing equity and inclusion must be considered on par with excellence in research and teaching”. Likewise, in an article describing their “cultural change initiative”, several deans at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine declared: “There is no priority in medical education that is more important than addressing and eliminating racism and bias.”

DEI has also become a priority for many of the organizations that accredit universities. Last year, the Council for Higher Education Accreditation, along with several other university accrediting bodies, adopted its own DEI statement, proclaiming that “the rich values of diversity, equity and inclusion are inextricably linked to quality assurance in higher education”. These accreditors, in turn, pressure universities and schools into adopting DEI measures.

Much of this happened by fiat, with little discussion. While interviewing more than two dozen professors for this article, I was told repeatedly that few within academia dare express their skepticism about DEI. Many professors who are privately critical of DEI declined to speak even anonymously for fear of professional consequences.

The Invention of DEI

How has this fundamental shift taken place? Gradually, then all at once.

For decades, university administrators have emphasized their commitment to racial diversity. In 1978, Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell delivered the court’s opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, taking up the question of racial preferences in higher education. Powell argued that racial preferences in admissions — in other words, affirmative action — could be justified on the basis of diversity, broadly defined. Colleges and universities were happy to adopt his reasoning, and by the 1980s, diversity was a popular rallying cry among university administrators.

By the 2010s, as the number of college administrators ballooned, this commitment to diversity was often backed by bureaucracies that bore such titles as “Inclusive Excellence” or “Diversity and Belonging”. Around 2013, the University of California system — which governs six of the nation’s top 50 ranked universities — began to experiment with mandatory diversity statements in hiring. Diversity statements became a standard requirement in the system by the end of the decade. The University of Texas at Austin in 2018 published a University Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan, which began to embed diversity committees throughout the university.

Then came the Black Lives Matter demonstrations of 2020. The response on campus was a virtual Cambrian explosion of DEI policies. Any institution that hadn’t previously been on board was pressured to make large-scale commitments to DEI. Those already committed redoubled their efforts. UT Austin created a Strategic Plan for Faculty Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity, calling for consideration of faculty members’ contributions to DEI when considering merit raises and promotion.

White Coats For Black Lives, a medical student organization that calls for the dismantling of prisons, police, capitalism, and patent law, successfully petitioned medical schools around the country to adopt similar plans, including at UNC–Chapel Hill, Oregon Health & Science University, and Columbia University. In some cases, administrators even asked White Coats For Black Lives members to help craft the new plans.

All at once, policies that previously seemed extreme — like DEI requirements for tenure and mandatory education in Critical Race Theory — became widespread.

Repurposing Obsolete Rifles: The Lebel R35 Carbine

Forgotten Weapons

Published 19 Dec 2017The French military had investigated the possibility of a Lebel carbine in the 1880s, but by the 1930s a different set of priorities was in place. In an effort to make some use of the vast stockpiles of obsolete Lebel rifles France had, a plan was put in place to shorten then into carbines for auxiliary troops like artillery crews and engineers. These men needed some sort of rifle or carbine, but they did not need the best and newest weapons. By giving them shortened Lebel carbines, it would free up more modern rifles like the M34 Berthiers in 7.5mm and the new MAS-36 rifles to go to the front line infantry who needed them most.

The R35 conversion was developed by the Tulle arsenal and adopted in January of 1936. The French government ordered 100,000 to be made, and deliveries began in April of 1937. Production would accelerate and continue right up to the spring of 1940, with a total of about 45,000 being actually delivered before the armistice with Germany. The conversions were all assembled at Tulle, but four other factories manufactured barrels for them: Chatellerault (MAC), St Etienne (MAS), Société Alsacienne de Constructions Mécaniques (SACM), and Manufacture d’Armes de Paris (MAP). These barrels were 450mm long (17.7 inches), and with the similarly shortened magazine tube, the R35 carbines held just 3 rounds. Production would not continue after the liberation of France in 1944.

(more…)

QotD: “Little” gods in the ancient world

When we teach ancient religion in school – be it high school or college – we are typically focused on the big gods: the sort of gods who show up in high literature, who create the world, guide heroes, mint kings. These are the sorts of gods – Jupiter, Apollo, Anu, Ishtar – that receive state cult, which is to say that there are rituals to these gods which are funded by the state, performed by magistrates or kings or high priests (or other Very Important People); the common folk are, at best, spectators to the rituals performed on their behalf by their social superiors.

That is not to say that these gods did not receive cult from the common folk. If you are a regular sailor on a merchant ship, some private devotion to Poseidon is in order; if you are a husband wishing for more children, some observance of Ishtar may help; if you are a farmer praying for rain, Jupiter may be your guy. But these are big gods, whose vast powers are unlimited in geographic scope and their right observance is, at least in part, a job for important people who act on behalf of the entire community. Such gods are necessarily somewhat distant and unapproachable; it may be difficult to get their attention for your particular issue.

Fortunately, the world is full up of smaller and more personal gods. The most pervasive of these are household gods – god associated with either the physical home, or the hearth (the fireplace), or the household/family as a social unit. The Romans had several of these, chiefly the Lares and Penates, two sets of gods who presided over the home. The Lares seem to have originally been hearth guardians associated with the family, while the Penates may have begun as the guardians of the house’s storeroom – an important place in an agricultural society! Such figures are common in other polytheisms too – the fantasy tropes of brownies, hobs, kobolds and the like began as similar household spirits, propitiated by the family for the services they provide.

(As an aside, the Lares and Penates provide an excellent example on how practice was valued more than belief or orthodoxy in ancient religion: when I say that they “seem” or “may have originally been”, that is because it was not entirely clear to the Romans, exactly what the distinction between the Lares and Penates were; ancient authors try to reconstruct exactly what the Penates are about from etymologies (e.g. Cic. De Natura Deorum 2.68) and don’t always agree! But of course, the exact origins of the Lares or the Penates didn’t matter so much as the power they held, how they ought to be appeased, and what they might do to you!)

Household gods also illuminate the distinctly communal nature of even smaller religious observances. The rituals in a Roman household for the Lares and Penates were carried out by the heads of the household (mostly the paterfamilias although the matron of the household had a significant role – at some point, we can talk about the hierarchy of Roman households, but now I just want to note that these two positions in the Roman family are not co-equal) on behalf of the entire family unit, which we should remember might well be multi-generational, including adult children with their own children – in just the same way that important magistrates (or in monarchies, the king or his delegates) might carry out rituals on behalf of the community as a whole.

There were other forms of little gods – gods of places, for instance. The distinction between a place and the god of that same place is often not strong – when Achilles enrages the god of the river Scamander (Iliad 20), the river itself rises up against him; both the river and the god share a name. The Romans cover many small gods under the idea of the genius (pronounced gen-e-us, with the “g” hard like the g in gadget); a genius might protect an individual or family […] or even a place (called a genius locus). Water spirits, governing bodies of water great and humble, are particularly common – the fifty Nereids of Greek practice, or the Germanic Nixe or Neck.

Other gods might not be particular to a place, but to a very specific activity, or even moment. Thus (these are all Roman examples) Arculus, the god of strongboxes, or Vagitanus who gives the newborn its first cry or Forculus, god of doors (distinct from Janus and Limentinus who oversaw thresholds and Cardea, who oversaw hinges). All of these are what I tend to call small gods: gods with small powers over small domains, because – just as there are hierarchies of humans, there are hierarchies of gods.

Fortunately for the practitioner, bargaining for the aid of these smaller gods was often quite a lot cheaper than the big ones. A Jupiter or Neptune might demand sacrifices in things like bulls or the dedication of grand temples – prohibitively expensive animals for any common Roman or Greek – but the Lares and Penates might be befriended with only a regular gift of grain or a libation of wine. A small treat, like a bowl of milk, is enough to propitiate a brownie. Many rituals to gods of small places amount to little more than acknowledging them and their authority, and paying the proper respect.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part IV: Little Gods and Big People”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-11-15.

January 10, 2023

The Early Emperors, Part 9 – Nero: Can We Trust the Sources?

seangabb

Published 25 Dec 2022This is a video record of a lecture given by Sean Gabb, in which he discusses the reasons for the black reputation possessed by the Emperor Nero.

The Roman Empire was the last and the greatest of the ancient empires. It is the origin from which springs the history of Western Europe and those nations that descend from Western Europe.

(more…)

Persuading women not to have families because it “helps the GDP”

In The Critic, Niall Gooch stands up for family life despite the regular hand-wringing articles pointing out just how “expensive” children are and how much money women forego in the working world to take time off and have a family, as if no other economic decisions in life have opportunity costs attached:

Every so often, a publication called something like Bosses Quarterly or Money Patrol will report a new study investigating the financial costs of having children. “Average child now costs £200,000”, they breathlessly inform us, or perhaps “Women Who Become Mothers Lose £400,000 In Earnings Over Their Lifetime”.

I have no idea how they generate these figures. Presumably they have at least some basis in proper empirical research. It doesn’t seem inherently implausible that middle-class parents in Britain spend well into six figures on their children one way and another, when you factor in childcare, holidays, clothes, food, transportation, birthday parties and university attendance. Raising children is undoubtedly costly, from a financial perspective, even if you are frugal. If my wife and I did not have children, our lifestyle would be considerably more affluent than it is at present. The “motherhood penalty” in lifetime wages does seem to be a real phenomenon – although it is one that many women are willing to accept.

But the accuracy or otherwise of the calculations is beside the point. There is something profoundly wrong-headed about the whole endeavour of trying to evaluate the good of family life in economic terms, or to treat the raising of children as simply one option among many in the great lifestyle marketplace. And yet many people persist with doing so. Sam Freedman, the policy analyst and writer, claimed on Twitter earlier this week, in defence of expanding subsidies for nurseries, that “it’s a lot cheaper for one person to look after several children than each parent to look after their own and not work”. This person noted “the long term impact on (nearly always) women’s career prospects which has a big effect on GDP”. He also argued against replacing subsidies to nurseries with direct payments to parents, noting that “giving money direct to parents would encourage people to leave the workforce when we need the opposite to happen”.

Even on its own terms, this is dubious. Low birth rates are a significant drag on economic growth, and making it harder for women to spend more time at home with their children is hardly conducive to increasing the birth rate. Besides which, there are big socio-economic problems connected to the modern norm of two parents working more or less full-time — house-price inflation for example, or the decline of communal organisations and lack of time for family caring responsibilities.

Catherine the Great & the Volga Germans

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 16 Aug 2022

(more…)

QotD: A useful life lesson

… it reemphasizes a life lesson that, like all truly useful life lessons, is lethally easy to forget. I’m not a gambling man, but you can bet the farm and the kids’ college fund on the phrase “surely they’d never be dumb enough to ____.” The very fact that you find yourself thinking “they’d never be dumb enough to ____” is a guarantee that they are, right now, at this very instant, ____.

Severian, “The Stakeholder State”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-22.

January 9, 2023

How to Carve a Bowl | Paul Sellers

Paul Sellers

Published 29 Jul 2022I can’t imagine any woodworker who wouldn’t at some point in their woodworking, want to carve a bowl from a chunk of wood using their hands and a couple of basic tools.

I put this together to show the basic steps and tools I suggest as patterns and methods of working to create a three-dimensional shaped object from solid wood.

You can use any wood you have as scraps, including construction lumber. It’s a neat couple of hours of work and great to do with the kids too.

——————–

(more…)

QotD: Property is theft

The French socialist philosopher who was much ridiculed by Marx as a sentimental petit-bourgeois moralist, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, is now remembered mainly for his aphorism, so good that he repeated it many times, “Property is theft”. But in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the reverse of this celebrated but preposterous dictum has actually become true: Theft is property.

Pictures of the looting that followed the devastation in New Orleans have been flashed around the world. Everyone is, or at least pretends to be, shocked and horrified, as if the breakdown of law and order couldn’t happen here, wherever here happens to be. Smugness is, after all, one of the most pleasant of feelings; but for myself, I have very little doubt that it could, and would, happen where I live, in Britain, under the same or similar conditions. New Orleans shows us in the starkest possible way the reality of the thin blue line that protects us from barbarism and mob rule.

Of course, an unknown proportion of the looting must have arisen from genuine need and desperation. Who among us would not help himself to food and water if he and his family were hungry and thirsty, and there were no other source of such essentials to hand?

But the pictures that have been printed in the world’s newspapers are not those of people maddened by hunger and thirst, but those of people wading through water clutching boxes of goods that are clearly not for immediate consumption. There are pictures of people standing outside stores, apparently discussing what to take and how to transport it, and of men loading the trunks of cars with a dozen cartons of nonessentials. They are thinking ahead, to when the normal economy reestablishes itself, and the goods that they have stolen will have a monetary value once more.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Veneer of Civilization”, Manhattan Institute, 2005-09-26.

January 8, 2023

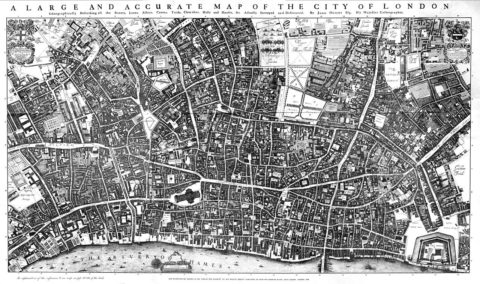

The (historical) lure of London

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the puzzle that was the phenomenol growth of London, even at a time that England had a competitive advantage in agricultural exports to the continent:

… the extraordinary inflow of migrants to London in the period when it grew eightfold — from an unremarkable city of a mere 50,000 souls in 1550, to one of the largest cities in Europe in 1650, boasting 400,000. I’ve written about that growth a few times before, especially here. It may not sound like much today, but it has to be one of the most important facts in British economic history. It is, in my view, the first sign of an “Industrial Revolution”, and certainly the first indication that there was something economically weird about England. It requires proper explanation.

In brief, the key question is whether the migrants to London — almost all of whom came from elsewhere in England — were pushed out of the countryside, thrown off their land thanks to things like enclosure, or pulled by London’s attractions.

I think the evidence is overwhelmingly that they were pulled and not pushed:

- The English rural population continued to grow in absolute terms, even if a larger proportion of the total population made their way to London. The population working in agriculture swelled from 2.1 million in 1550 to about 3.3 million in 1650. Hardly a sign of widespread displacement.

- As for the people outside of agriculture, many remained in or even fled to the countryside. In the 1560s, for example, York’s textile industry left for the countryside and smaller towns, pursuing lower costs of living and perhaps trying to escape the city’s guild restrictions. In 1550-1650, the population engaged in rural industry — largely spinning and weaving in their homes — swelled from about 0.7 to 1.5 million. Again, it doesn’t exactly suggest rural displacement. If anything, the opposite.

- There were in fact large economic pressures for England to stay rural. England for the entire period was a net exporter of grain, feeding the urban centres of the Netherlands and Italy. The usual pattern for already-agrarian economies, when faced with the demands of foreign cities, is to specialise further — to stay agrarian, if not agrarianise more. It’s what happened in much of the Baltic, which also fed the Dutch and Italian cities. Despite the same pressures for England to agrarianise, however, London still grew. To my mind, it suggests that London had developed an independent economic gravity of its own, helping to pull an ever larger proportion of the whole country’s population out of agriculture and into the industries needed to supply the city.

- As for the supposed push factor, enclosure, the timing just doesn’t fit. Enclosure had been happening in a piecemeal and often voluntary way since at least the fourteenth century. By 1550, before London’s growth had even begun, by one estimate almost half of the country’s total surface had already been enclosed, with a further quarter gradually enclosed over the course of the seventeenth century. A more recent estimate suggests that by 1600 already 73% of England’s land had been enclosed. As for the small remainder, this was mopped up by Parliament’s infamous enclosure acts from the 1760s onwards — much too late to explain London’s population explosion.

- Perhaps most importantly, people flocked specifically to London. In 1550 only about 3-4% of the population lived in cities. By 1650, it was 9%, a whopping 85% of whom lived in London alone. And this even understates the scale of the migration to the city, because so many Londoners were dropping dead. It was full of disease in even a good year, and in the bad it could lose tens of thousands — figures equivalent or even larger than the entire populations of the next largest cities. Waves upon waves of newcomers were needed just to keep the city’s population stable, let alone to grow it eightfold. In the seventeenth century the city absorbed an estimated half of the entire natural increase in England’s population from extra births. If England’s urbanisation had been thanks to rural displacement, you’d expect people to have flocked to the closest, and much safer, cities, rather than making the long trek to London alone.

It’s this last point that I’ve long wanted to flesh out some more. The further people were willing to trek to London, the more strongly it suggests that the city had a specific pull. I’d so far put together a few dribs and drabs of evidence for this. Whereas towns like Sheffield drew its apprentices from within a radius of about twenty miles, London attracted young people from hundreds of miles away, with especially many coming from the midlands and the north of England. Indeed, London’s radius seems to have shrunk over the course of the seventeenth century, suggested that they came from further afield during the initial stages of growth. Records of court witnesses also suggest that only a quarter of men in some of London’s eastern suburbs were born in the city or its surrounding counties.

“Russians 27 miles from Poland!” – Ep 228 – January 7, 1944

World War Two

Published 7 Jan 2023That’s what the headlines say as the Red Army continues its advance in Ukraine. There are also plans afoot for a northern offensive to end the siege of Leningrad. There are also plans afoot for an Allied amphibious attack in Italy at Anzio. Both of these are set to go off within a couple weeks, so January promises to be full of active conflict.

(more…)