BBC Earth Lab

Published 21 Feb 2013James May talks us through the rise and fall of airships.

James May’s Q&A:

With his own unique spin, James May asks and answers the oddball questions we’ve all wondered about from “What Exactly Is One Second?” to “Is Invisibility Possible?”

April 26, 2020

Where have all the airships gone? | James May’s Q&A (Ep 8) | Head Squeeze

April 24, 2020

Prizes, patents, and the Society of the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the Society of the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts) wasn’t a fan of the British patent system and preferred to award prizes in areas that were unlikely to generate monopoly situations:

The back of the Royal Society of Arts building in London, 25 August 2005.

Photo by C.G.P. Grey (www.CGPGrey.com) via Wikimedia Commons.

… the Society’s early members had an aversion to monopolies, and patents are, after all, temporary monopolies. But there was actually a more practical reason to not give rewards to patented inventions. In fact, quite a few active members of the Society were themselves patentees, and patents for inventions were not generally lumped together for condemnation with practices like forestalling and engrossing. The practical reason for banning patents was that there was no point giving a prize for something that people were already doing anyway. Patents were expensive in the eighteenth century — depending on how you account for inflation, it could cost about £300,000 in modern terms to obtain one — so the fact that there was a patent for a process was a clear indication that it might be profitable. The Society, by contrast, was supposed to encourage things that would not otherwise have been done.

Thus, when a patent had already been granted for a process the Society had been considering giving a premium for, it purposefully backed down — not because the prize would infringe on the patent, but because its encouragement was no longer necessary. And so the effect of the ban on patented inventions was that the Society received, even unsolicited, exactly the kinds of inventions that there was less monetary incentive to invent. Occasionally, this meant trivial improvements — minor tweaks, here and there, to existing processes. An engineer might patent one invention, but not see it worth their time patenting another — through the Society’s prizes, they might at least get a bit of cash for it, or some recognition. The improvement would also be promoted through the Society’s publications. Or, the Society received inventions that were far from trivial, like the scandiscope for cleaning chimneys [here], but which were not all that profitable: inventions that saved lives, or had other beneficial effects on the health and wellbeing of workers and consumers. And finally, the Society received innovations that could not be patented, such as agricultural practices and the opening of new import trades. In the early nineteenth century the Society awarded its prizes to a whole host of naval officers, including an admiral, who came up with flag-based signalling systems between ships — early forms of semaphore.

Another effect of the ban on patents was that the Society also attracted submissions from different demographics. Many of its submissions came from people who were too poor to afford patents, as well as from those who were too rich — wealthy aristocrats for whom commercial considerations might seem vulgar. The poor would generally go for the cash prizes, and the aristocrats for the honorary medals. And the prizes were used by people who might otherwise be socially excluded from invention. In 1758, for example, the Society instructed its members in the American colonies to accept submissions from Native Americans. It also allowed women to claim premiums (just as it allowed them to be members). My favourite example is Ann Williams, postmistress at Gravesend, in Kent, who won twenty guineas from the Society in 1778 for her observations on the feeding and rearing of silk-worms. She kept them in one of the post-office pigeon-holes, referring to them affectionately as “my little family” of “innocent reptiles”. Unlike other elements of society, the Society of Arts accepted, as she put it to them, that “curiosity is inherent to all the daughters of Eve.”

The Society thus encouraged the kinds of inventions that might not otherwise have been created, and catered to the kinds of inventors who might not otherwise have been recognised. Rather than competing with the patent system, it complemented it, filling in the gaps that it left. The Society operated at the margins, and only at the margins, to the better completion of the whole. It found its niche, to the benefit of innovation overall.

April 22, 2020

Can We Build A Space Elevator? | Earth Lab

BBC Earth Lab

Published 5 Aug 2013Getting to space in a rocket is expensive! One of the most popular alternative ideas is the space elevator, but is it really possible?

Here at BBC Earth Lab we answer all your curious questions about science in the world around you. If there’s a question you have that we haven’t yet answered or an experiment you’d like us to try let us know in the comments on any of our videos and it could be answered by one of our Earth Lab experts.

April 15, 2020

The Industrial Revolution and the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce

In the latest from Anton Howes’ Age of Invention newsletter, we are introduced to the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce:

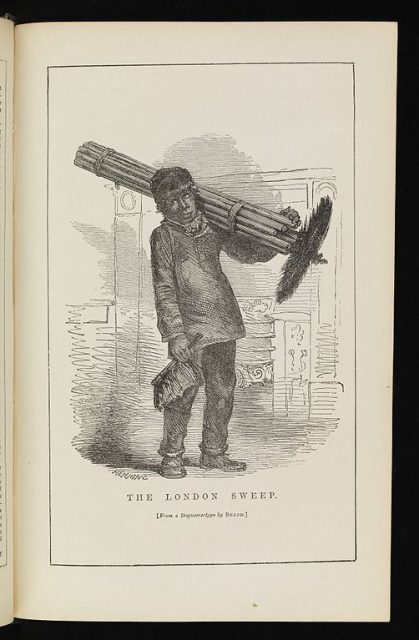

The London Sweep (from a Daguerreotype by BEARD).

Image from London labour and the London poor : a cyclopaedia of the condition and earnings of those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work, 1851, via the Wellcome Collection.

When we think of the British Industrial Revolution, the image that springs to mind tends to be of soot-belching factories and foundries, of child labour and squalid cities. The inventors who spring to mind tend to be James Watt and his steam engines, or Richard Arkwright and his cotton-spinning machines. But what people tend to forget is that the Industrial Revolution was unleashed by a much broader tide of accelerating innovation — as I never tire of repeating, it touched everything from agriculture to watchmaking, and everything inbetween. Just as some inventors pioneered the use of factories, other inventors sought solutions to industrialisation’s social ills.

Last time, I mentioned the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, set up in 1754 in a London coffee house (the Society of Arts for short). What’s so fascinating about the organisation — which still exists today, now called “Royal” — is that it was closely involved with many of the more socially-oriented innovations of the period. By this, I mean the kinds of inventions that were rarely immediately profitable, but which aimed to save lives, to alleviate suffering, or to remedy some other social ill. The Society advertised premiums — cash prizes or honorary medals — for solutions to the problems that its members identified. And it offered similar rewards, which they called bounties, for unsolicited inventions.

It awarded a bounty of fifty guineas and a gold medal to Henry Greathead, for example, one of the claimants for the invention of the lifeboat. It gave another fifty guineas to a sergeant of the Royal Artillery, John Bell, for a method of firing a rope and grapple by mortar from a ship to the shore, to save people on board from shipwreck during storms. (Some years later, it even gave a gold medal to another inventor for a device that did the opposite, firing from shore to ship.) The Society awarded a medal to a Sheffield schoolmaster, John Hessey Abraham, for a magnetic apparatus that would prevent metal dust getting into the eyes and lungs of workers employed in grinding the points of needles. And in 1767 it awarded a bounty to a clockmaker, Christopher Pinchbeck, for a safer crane — cranes at the time were like gigantic hamster wheels, but for humans. When lines snapped, the results could be fatal, so Pinchbeck added a pneumatic braking mechanism.

The list goes on — in all, over the course of about a century, the Society of Arts awarded over two thousand premiums and bounties for inventions. But there is one that really stands out: a premium for the invention of a mechanical means of cleaning chimneys. With such an invention, the Society hoped to abolish the employment of children, sometimes as young as 4, who were forced to climb up inside chimneys in order to clean them. These children were sometimes abducted by the master chimney sweeps, and frequently perished in horrific accidents or of soot-induced cancers. Strikingly, the use of climbing boys was thought to be unique to Britain — the “peculiar disgrace of England” as the campaigners put it (though I don’t think this was quite true). The Society’s idea was that if a technological replacement could be found, then the case for outright abolition could be made — they wanted to create a machine to take the children’s jobs.

The Society of Arts played its role with the offer of a premium, but it acted alongside another campaign run by a few of its members, who ran the snappily titled “Society for Superseding the Necessity of Climbing Boys, by Encouraging a New Method of Sweeping Chimnies, and for Improving the Condition of Children and Others Employed by Chimney Sweepers”, founded in 1803 at the London Coffee-House on Ludgate Hill. Let’s call it the SSNCB for short. There had been earlier campaigns to abolish the use of climbing boys, one of the most prominent being run by Jonas Hanway (a prominent philanthropist, also a member of the Society of Arts, whose various claims to fame include being the first man in London to sport an umbrella). But the 1803 campaign was to prove the most successful, drawing on wider political support. The SSNCB’s key members included William Wilberforce, who later became famous for his zeal in abolishing the slave trade.

“Experts” and their “models”

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, after offering us his current favourite mixed drink recipe, L. Neil Smith gets around to discussing our modern dependence on “experts” wielding their intricate and convoluted computer models to guide our lives:

Start with a tall glass of Mott’s Clamato over ice. Many people can’t stand the idea of tomato juice enhanced with sweet clam juice (and some spices), and I won’t try to sell you on it, here. But if you relish it the way I do (I used to buy it by the gallon), then bon appetit! Throw in a healthy shot of tequila — mine is Cuervo Gold, but your mileage may vary. Add a fat slice of lime on the edge of the glass, a slice of lemon, and a slice of orange. The citrus really dresses it up. These are all ingredients I like very much, and together, they take the edge off a day I spent writing 1000 or 2000 words (my record so far is 3200) and let me relax.

At the end of that day, when my lovely and talented wife quits work and comes home — from the dining room, these days — we have a nice, comfortable cocktail hour (she drinks Cuba Libras) and watch Tucker Carlson. Ordinarily, three giant cans of the Budweiser concoction (which is also made with Clamato) will make me the tiniest bit silly. This drink, the Bloody Mermaid (ick) is surprisingly gentle and I have had two and a half so far without embarrassing myself. I love the taste of tequila neat (many don’t), and I would still be doing shooters, except that my loving bride of 36 years won’t let me eat that much salt.

Please enjoy this silly little drink if you can until we’re all free again.

Oh yeah — I couldn’t resist after all. There’s something I need to get off my chest. I’m sure you remember the way “experts” with computer models warned us all about Y2K, and the way it meant the end of Civilization-As-We-Knew-It. Then there was Global Warming — more experts, more computer models — there are still gullible morons out there who believe it’s not an obvious hoax. Now experts and their — increasingly failing — computer models are all telling us we are in the middle of the worst health crisis since the Black Death.

I happen to be, as you know, a lifelong libertarian and the most fervid advocate of the First Amendment that you will ever read. Therefore, I cannot endorse the suggestion I’ve heard that whenever an “expert” testifies about anything before any legislative body anywhere, and the words “computer model” come out of his mouth, the Sergeant-at-Arms should smash his face in, drag him out into the street, and shoot him him the back of the head. Perhaps millions of lives could be saved that way, but, as a lifelong libertarian and the most fervid advocate of the First Amendment you will ever read, I cannot endorse that position.

So drink up, my dear friends and readers and have the best time — under house arrest — that you possibly can!

April 4, 2020

Eighteenth century health improvements through “ventilators”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes relates how a mistaken belief still led to a significant improvement in health:

One of the most worrying diseases of the mid-eighteenth century was typhus. We now know that it is spread by lice or fleas, but at the time, like so many other diseases, it was thought to be caused by noxious air — “malaria”, for example, literally means “bad air”. This was not a silly theory. It was based on empirical observation, which perhaps explains why the belief in such noxious miasmas persisted for so long — well into the late nineteenth century, if not the early twentieth, before finally being ousted by germ theory. Our ancestors were not stupid, no matter how strange their beliefs might appear in hindsight. (Also take alchemy, or the belief that some animals spontaneously generated.)

The Central Tower of the Palace of Westminster is actually a disguised ventilator.

Photo by Cary Bass via Wikimedia Commons.Typhus fit the miasma theory especially well because it frequently appeared in confined spaces, like ships’ holds, prisons, mines, workhouses, and hospitals. The disease was thus often called “gaol fever”, or “hospital fever”. And there was the fact that at least one of the solutions designed to combat miasmas, the ventilator, actually seemed to work. This ventilator was not the kind that is in such high demand right now, used to help feed oxygen into patients’ lungs, but instead a machine used to get the air flowing in and out of confined spaces — like a 1740s air-conditioning unit.

At first glance, removing the stale air from a space shouldn’t do anything against typhus. But mortality declined drastically in the prisons and ships to which the ventilator was introduced. It halved the number of deaths per year in Newgate prison, where the bellows-like machinery was powered by a windmill, and the inmates of the Savoy prison fared even better. On ships, too, mortality declined among mariners, passengers, soldiers, and especially among the group that suffered most from long voyages across the eighteenth-century Atlantic: slaves.

But it’s not clear exactly why. After all, the ventilator did not kill the typhus-ridden lice or fleas. I have a few theories as to what must have been going on. Perhaps, by improving the supply of oxygen to confined spaces, people’s bodies were simply better served to deal with all manner of diseases. Surgeons aboard slave ships sometimes noted that, without proper ventilation, many slaves would simply die in the night of suffocation. Or perhaps the ventilator’s effectiveness had something to do with its drying effect. The machine was used to prevent grain stores from becoming humid, thus staving off damp-loving weevils. The ventilators might thus have staved off typhus through a similar means: although I’m not so certain about body lice, humid conditions are preferred by fleas. Regardless of the real reasons, the ventilators worked, and even when they did not reduce mortality, they made confined spaces more bearable for those who had to endure them. Ship captains reported that they did not even have to force their sailors to pump the ventilator’s bellows, because they liked the cool air so much. Ventilators were soon installed in the House of Commons, and in many of London’s theatres.

From the Wikipedia entry on architectural ventilation:

The development of forced ventilation was spurred by the common belief in the late 18th and early 19th century in the miasma theory of disease, where stagnant ‘airs’ were thought to spread illness. An early method of ventilation was the use of a ventilating fire near an air vent which would forcibly cause the air in the building to circulate. English engineer John Theophilus Desaguliers provided an early example of this, when he installed ventilating fires in the air tubes on the roof of the House of Commons. Starting with the Covent Garden Theatre, gas burning chandeliers on the ceiling were often specially designed to perform a ventilating role.

Mechanical systems

A more sophisticated system involving the use of mechanical equipment to circulate the air was developed in the mid 19th century. A basic system of bellows was put in place to ventilate Newgate Prison and outlying buildings, by the engineer Stephen Hales in the mid-1700s. The problem with these early devices was that they required constant human labour to operate. David Boswell Reid was called to testify before a Parliamentary committee on proposed architectural designs for the new House of Commons, after the old one burned down in a fire in 1834. In January 1840 Reid was appointed by the committee for the House of Lords dealing with the construction of the replacement for the Houses of Parliament. The post was in the capacity of ventilation engineer, in effect; and with its creation there began a long series of quarrels between Reid and Charles Barry, the architect.Reid advocated the installation of a very advanced ventilation system in the new House. His design had air being drawn into an underground chamber, where it would undergo either heating or cooling. It would then ascend into the chamber through thousands of small holes drilled into the floor, and would be extracted through the ceiling by a special ventilation fire within a great stack.

Reid’s reputation was made by his work in Westminster.

March 31, 2020

March 11, 2020

How Does It Work: Roller Locking

Forgotten Weapons

Published 10 Mar 2020http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Roller locking is a system that is not used in many guns and often confused with roller-delayed blowback — which is understandable, given the similarities between the systems. Roller locking was first developed as a modification of the German G43 rifle, and it is really a sub-type of flapper locking mechanism. It was most significantly used in the MG42, and also in the Czech vz.52 pistol. In essence, it uses rollers in place of flaps to lock the bolt and barrel securely together during firing, and depends on an external system (short recoil, in the case of the MG42 and vz.52) to unlock before it can cycle.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

March 10, 2020

Thought-saving inventions

In the latest issue of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the innovations that helped provide short-cuts for thought, rather than labour:

The world on Mercator projection between 85°3’4″S and 85°3’4″N, such that image is square. 15° graticule. Imagery is a derivative of NASA’s Blue Marble summer month composite with oceans lightened to enhance legibility and contrast. Image created with the Geocart map projection software.

Image by Strebe via Wikimedia Commons.

When we think of labour-saving inventions, the kind of labour that springs to mind tends to be manual. We think of machines replacing the muscle of limbs and the dexterity of fingers, and we worry about their effects on unemployment and unrest. But there’s a subset of labour-saving inventions that rarely gets discussed. They might best be called thought-saving.

A few weeks ago I mentioned the introduction of mathematical techniques to navigation. Before the mid-sixteenth century in England, pilots very rarely even knew how to calculate their latitude, let alone their longitude. But over the course of just a few decades, England became one of the world leaders in navigational improvements. A handful of mathematicians saved pilots the trouble of calculation, by coming up with tables, instruments, diagrams, and rules of thumb. In the process, they improved navigation’s accuracy, and ushered in an age of English dominance of the high seas.

The historian Eric H. Ash gives a few great examples. In the 1590s, the explorer John Davis shared a way to calculate the time of high tide, without requiring multiplication. Likewise, William Bourne, a self-taught mathematician and gunner, in the 1560s provided an easy means of calculating the linear distance in one degree of longitude, at any given latitude. He provided a diagram — really an instrument, even if it wasn’t made of wood or brass — which with just a simple piece of string could be used to derive the answer without needing to understand cosines, or really any trigonometry.

The mathematicians did the same with maps, too (after all, aren’t all maps thought-saving?) The sixteenth-century cartographic innovations simplified the pilot’s ability to chart a route, for example by taking away all need to worry about the curvature of the earth. The famous 1560s map projection of Gerardus Mercator stretched the distance between the lines of latitude as they got closer to the poles, so that charting a course on such a map was a simple matter of drawing straight lines rather than complex trigonometry. The Mercator projection may well make Africa look smaller than Greenland — it’s actually almost fifteen times as large — but it made life significantly easier for mariners. For similar reasons, the mathematician John Dee designed a special chart — what he called the “paradoxall compass” — to aid the English explorers who in the 1550s went in search of a northeast and northwest passage to Asia. Conventional charts made navigating high latitudes confusing, as the north pole was a straight line — the map’s top border. Dee’s map made things easier by putting the pole at the centre, as a point, with the lines of latitude as concentric circles.

March 4, 2020

England’s Secret Weapon: The Two Million Ton Megacarrier Made of Ice

Today I Found Out

Published 16 Feb 2018If you happen to like our videos and have a few bucks to spare to support our efforts, check out our Patreon page where we’ve got a variety of perks for our Patrons, including Simon’s voice on your GPS and the ever requested Simon Whistler whistling package: https://www.patreon.com/TodayIFoundOut

This video is sponsored by World of Warships

In this video:

Britain was taking a beating from the German ships and submarines and were looking for something to build a ship out of that couldn’t be destroyed by torpedoes, or at least could take a major pounding without incurring a fatal amount of damage. With steel and aluminum in short supply, Allied scientists and engineers were encouraged to come up with alternative materials and weapons.

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.p…

February 29, 2020

The metallic nickname of Henry VIII

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the rocky investment history for German mining firms in England during the Tudor period:

Cropped image of a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait of King Henry VIII at Petworth House.

Photo by Hans Bernhard via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s an especially interesting case of England’s technological backwardness, given that copper was a material of major strategic importance: a necessary ingredient for the casting of bronze cannon. And it was useful for other industries, especially when mixed with zinc to form brass. Brass was the material of choice for accurate navigational instruments, as well as for ordinary pots and kettles. Most importantly, brass wire was needed for wool cards, used to straighten the fibres ready for spinning into thread. A cheaper and more secure supply of copper might thus potentially make England’s principal export, woollen cloth, even more competitive — if only the English could also work out how to produce brass.

The opportunity to introduce a copper industry appeared in 1560, when German bankers became involved in restoring the gold and silver content of England’s currency. The expensive wars of Henry VIII and Edward VI in the 1540s had prompted debasements of the coinage, to the short-term benefit of the crown, but to the long-term cost of both crown and country. By the end of Henry VIII’s reign, the ostensibly silver coins were actually mostly made of copper (as the coins were used, Henry’s nose on the faces of the coins wore down, revealing the base metal underneath and earning him the nickname Old Coppernose). The debased money continued to circulate for over a decade, driving the good money out of circulation. People preferred to hoard the higher-value currency, to send it abroad to pay for imports, or even to melt it down for the bullion. The weakness of the pound was an especial problem for Thomas Gresham, Queen Elizabeth’s financier, in that government loans from bankers in London and Antwerp had to be repaid in currency that was assessed for its gold and silver content, rather than its face value. Ever short of cash, the government was constantly resorting to such loans, made more expensive by the lack of bullion.

Restoring the currency — calling in the debased coins, melting them down, and then re-minting them at a higher fineness — required expertise that the English did not have. From France, the mint hired Eloy Mestrelle to strike the new coins by machine rather than by hand. (He was likely available because the French authorities suspected him of counterfeiting — the first mention of him in English records is a pardon for forgery, a habit that apparently died hard as he was eventually hanged for the offence). And to do the refining, Gresham hired German metallurgists: Johannes Loner and Daniel Ulstätt got the job, taking payment in the form of the copper they extracted from the debased coinage (along with a little of the silver). It turned out to be a dangerous assignment: some of the copper may have been mixed with arsenic, which was released in fumes during the refining process, thus poisoning the workers. They were prescribed milk, to be drunk from human skulls, for which the government even gave permission to use the traitors’ heads that were displayed on spikes on London Bridge — but to little avail, unfortunately, as some of them still died.

Loner and Ulstätt’s payment in copper appears to be no accident. They were agents of the Augsburg banking firm of Haug, Langnauer and Company, who controlled the major copper mines in Tirol. Having obtained the English government as a client, they now proposed the creation of English copper mines. They saw a chance to use England as a source of cheap copper, with which they could supply the German brass industry. It turns out that the tale of the multinational firm seeking to take advantage of a developing country for its raw materials is an extremely old one: in the 1560s, the developing country was England.

Yet the investment did not quite go according to plan. Although the Germans possessed all of the metallurgical expertise, the English insisted that the endeavour be organised on their own terms: the Company of Mines Royal. Only a third of the company’s twenty-four shares were to be held by the Germans, with the rest purchased by England’s political and mercantile elite: people like William Cecil (the Secretary of State) and the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley (the Queen’s crush). It was an attractive investment, protected from competition by a patent monopoly for mines of gold, silver, copper, and mercury in many of the relevant counties, as well as a life-time exemption for the investors from all taxes raised by parliament (in those days, parliament was pretty much only assembled to legitimise the raising of new taxes).

Dardick Model 1500: The Very Unusual Magazine-fed Revolver

Forgotten Weapons

Published 12 Nov 2019This is Lot 1953 in the upcoming RIA December Premier auction.

The Dardick 1500 was a magazine-fed revolver designed by David Dardick in the 1950s. His patent was granted in 1958, and somewhere between 40 and 100 of the guns were made in 1959, before the company went out of business in 1960. The concept was based around a triangular cartridge (a “tround”) and a 3-chambered, open-sided cylinder. This wasn’t really of direct benefit to a handgun, but instead was ideal for a high rate of fire machine gun, where the system did not need to pull rounds forward or backward to chamber and eject them. In lieu of military machine gun contract, Dardick applied the idea to a sidearm.

The Model 1500 held 15 rounds, inside a blind magazine in the grip. It was chambered for a .38 caliber cartridge basically the same as .38 Special ballistically. A compact Model 1100 was also made in a small numbers, with a shorter grip and correspondingly reduced magazine capacity (11 trounds). A carbine barrel/stock adapter was also made. The guns were a complete commercial failure, with low production and lots of functional problems. Today, of course, they are highly collectible because of that scarcity and their sheer mechanical weirdness.

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85704

I’ve always had an interest in the Dardick, from their appearance in some of L. Neil Smith’s science fiction novels. I linked to an earlier article of his, and commented:

As Neil pointed out in one of his books, the Dardick was the answer to a bad crime writer’s prayers: it was literally an automatic revolver. (For those following along at home, an “automatic” has a magazine holding the bullets which are fed into the chamber to be fired by the action of the weapon: fire a bullet, the action cycles, clearing the expended cartridge and pushing a new one into place, cocking the weapon to fire again. A “revolver” holds bullets in the cylinder, rotating the cylinder when the gun is fired to put a new bullet in line with the barrel to be fired. The Dardick is the only example I know of that combines both in one gun.)

February 23, 2020

February 20, 2020

So that’s why John Cabot got hired!

Anton Howes explains something that I’d wondered about in the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter:

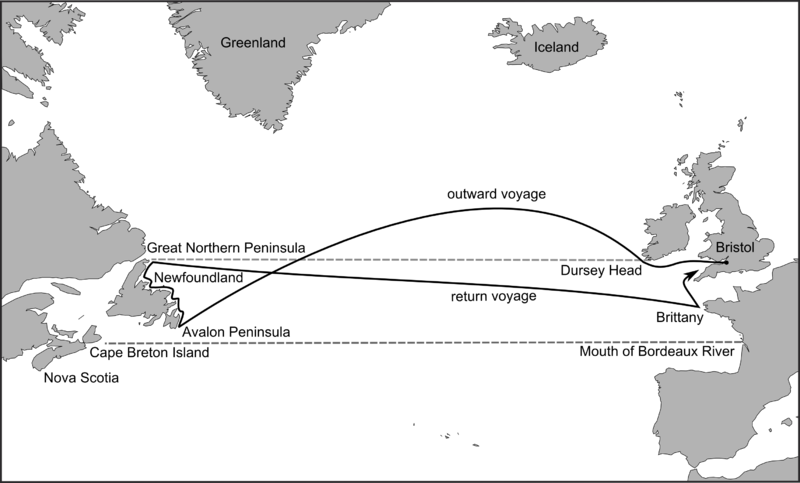

Route of John Cabot’s 1497 voyage on the Matthew of Bristol posited by Jones and Condon: Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, Nov. 2016), fig. 8, p. 43.

Wikimedia Commons.

… in 1550 the English were still struggling with latitude. Their inability to find it, unlike their Spanish and Portuguese rivals, was one of the main things holding them back from voyages of exploration.

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.The traditional method of navigation for English pilots was to simply learn the age-old routes. They were trained through repetition and accrued experience, learning to recognise particular landmarks and using a lead and line – just a thin rope weighted with some lead – to determine their location from the depth of the water. Cover the lead with something sticky, and you might bring up some sediment from the sea floor to double-check: a pilot would learn the kinds of sand and pebbles from to expect from different areas. And when they travelled out to sea, away from the coastline, they used a basic system of dead reckoning, taking their compass bearings from a known location, estimating their speed, and keeping in a particular direction for long enough. Or at least hoping to. They might keep track of their progress on a wooden traverse table, inserting pegs to indicate how far they had sailed, but it was ultimately a matter of rough estimation. Should they make any mistake — in terms of their speed, heading, or point of departure — they might easily get lost. But it was still a matter of trying to follow an already-known route. And English mariners of the 1550s did not even know that many routes.

For a voyage of exploration, by contrast, landmarks and sediment from the sea floor would be seen for the first time rather than recalled. By definition, there was no route to follow. So to launch their own voyages of discovery, the English needed to learn a new skill. They needed to look to the heavens.

Celestial navigation — measuring the altitude of heavenly bodies and then using geometry to determine one’s latitude on the earth’s surface — was by the 1550s already hundreds of years old. It had primarily been used to cross the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East — seas of sand, in which there might also be no landmarks from which to take bearings — and to navigate the Indian Ocean. Thus, while pilots in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean stuck to dead reckoning and soundings, Islamic navigators had for centuries used quadrants and astrolabes to take their bearings at sea. By the mid-fifteenth century, these instruments and techniques had found their way to Europe, where they were put to use especially by Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian explorers, along with additional instruments such as the cross-staff.

[…]

So for decades, English explorations relied on foreigners who either knew the routes that the English pilots didn’t, or who at least possessed the skill of mathematical, celestial navigation. The Italian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Chabotto), when he sailed to Newfoundland from Bristol in the late 1490s, was able to take latitude readings (he may even have been familiar with the older Islamic navigational practices, as he claimed to have visited Mecca). When Cabot died, the English expeditions that set out from Bristol in 1501-3 relied on Portuguese pilots from the mid-Atlantic islands of the Azores. And John Cabot’s son, Sebastian Cabot, who was involved in a few English expeditions, was so expert in mathematical navigation that he was eventually appointed pilot major for the entire Spanish Empire, making him responsible for the training and licensing of all its pilots — a position he held for three decades. When he led a voyage of exploration on behalf of Spain in 1526-30, a few English merchants became investors so that they could justify sending with him an English mariner, Roger Barlow, to secretly learn the Spanish routes across the Atlantic and have immediate knowledge if an onward route to Asia was discovered (as it turned out, South America got in the way).

February 14, 2020

Innovation and the “low-hanging fruit”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes wonders about the “low-hanging fruit” theories on innovation and why some things that seem obvious in hindsight took so long to be noticed:

A theme I keep coming back to is that a lot of inventions could have been invented centuries, if not millennia, before they actually were. My favourite example is John Kay’s flying shuttle, one of the most famous inventions of the British Industrial Revolution. It radically increased the productivity of weaving in the 1730s, but involved simply attaching a little extra wood and string. It involved no new materials, was applied to the weaving of wool — England’s age-old industry — and required no special skill or science. Weaving had been “performed for upwards of five thousand years, by millions of skilled workmen, without any improvement being made to expedite the operation, until the year 1733”, was how Bennet Woodcroft — one of the nineteenth century’s most important historians of technology — put it. (Lest you doubt that description of Woodcroft, he was, in addition to being an inventor himself, the man who compiled and categorised England’s entire patent record up to 1852, and who collected the inventions that would later form the basis of London’s Science Museum, particularly some of the earliest steam engines — among the most important machines in human history — that grace its engine hall today. My hero!) Weavers had been around for millennia, as had shuttles: one is even mentioned in the Old Testament (“My days are swifter than a weaver’s shuttle, And are spent without hope”). As a labour-saving invention, Kay’s flying shuttle was even technically illegal.

I keep coming back to this example, because it goes against so many common notions about the causes of innovation. When it comes to skill, materials, science, institutions, or incentives, none of them quite seem to fit. But I keep seeing more and more such cases. There’s the classic example, of course, of suitcases with wheels — why so late? Was the bicycle another candidate?

It strikes me as odd, too, that there was an explosion of signalling systems like semaphore only towards the end of the eighteenth century. Although there were some seventeenth-century precursors, the main telegraphing systems in Europe seem to have been as crude as Gondor’s lighting of the beacons, capable only of communicating a single pre-agreed message. Ancient China at least had its smoke signals, as did many indigenous American societies, and apparently the ancient Greeks too. So what took semaphore so long to take off? Many of the eighteenth-century systems did not even need multicoloured flags, my favourite being Lieutenant James Spratt’s “homograph”, subtitled “every man a signal tower”, which involved just a long white handkerchief.

The economist Alex Tabarrok calls these cases “ideas behind their time“. I tend to just call them low-hanging fruit. Hanging so low, and for so long, that the fruit are fermenting on the ground. I now see them everywhere, not just in history, but today — probably at least one per week.