The people most likely to grasp that wealth can be created are the ones who are good at making things, the craftsmen. Their hand-made objects become store-bought ones. But with the rise of industrialization there are fewer and fewer craftsmen. One of the biggest remaining groups is computer programmers.

A programmer can sit down in front of a computer and create wealth. A good piece of software is, in itself, a valuable thing. There is no manufacturing to confuse the issue. Those characters you type are a complete, finished product. If someone sat down and wrote a web browser that didn’t suck (a fine idea, by the way), the world would be that much richer.*

Everyone in a company works together to create wealth, in the sense of making more things people want. Many of the employees (e.g. the people in the mailroom or the personnel department) work at one remove from the actual making of stuff. Not the programmers. They literally think the product, one line at a time. And so it’s clearer to programmers that wealth is something that’s made, rather than being distributed, like slices of a pie, by some imaginary Daddy.

It’s also obvious to programmers that there are huge variations in the rate at which wealth is created. At Viaweb we had one programmer who was a sort of monster of productivity. I remember watching what he did one long day and estimating that he had added several hundred thousand dollars to the market value of the company. A great programmer, on a roll, could create a million dollars worth of wealth in a couple weeks. A mediocre programmer over the same period will generate zero or even negative wealth (e.g. by introducing bugs).

This is why so many of the best programmers are libertarians. In our world, you sink or swim, and there are no excuses. When those far removed from the creation of wealth — undergraduates, reporters, politicians — hear that the richest 5% of the people have half the total wealth, they tend to think injustice! An experienced programmer would be more likely to think is that all? The top 5% of programmers probably write 99% of the good software.

Wealth can be created without being sold. Scientists, till recently at least, effectively donated the wealth they created. We are all richer for knowing about penicillin, because we’re less likely to die from infections. Wealth is whatever people want, and not dying is certainly something we want. Hackers often donate their work by writing open source software that anyone can use for free. I am much the richer for the operating system FreeBSD, which I’m running on the computer I’m using now, and so is Yahoo, which runs it on all their servers.

* This essay was written before Firefox.

Paul Graham, “How to Make Wealth”, Paul Graham, 2004-04.

April 11, 2022

QotD: Programmers as craftsmen

April 10, 2022

April 6, 2022

Proposed new Canadian censorship rules will ███████ the ████████ unless we ████ ██

In The Line, Josh Dehaas waves off accusations against Trudeau while also highlighting just how censorious his governments proposed internet bill can be to freedom of expression online:

Comparisons of our prime minister to a dictator are self-evidently ridiculous. But the Russian example is still a case study in the harms of governments having too much power over the flow of information and ideas in a society. Trudeau is no dictator but he does helm a government in which overreach is becoming a frequent and habitual complaint. And one such area in which this government’s more illiberal tendencies are beginning to show is in the realm of media regulation. Despite pushback from groups like the Canadian Constitution Foundation and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, the Trudeau government seems determined to press ahead with laws to control what you read, write, watch and hear online.

The Liberals have long promised three bills aimed at countering three ostensible problems with online speech. The first bill aims to correct the problem of too few people choosing CanCon, by manipulating what you watch and listen to on platforms like Netflix and Spotify. The second bill would address the problem of advertisers ditching legacy newspapers for Facebook and Google. (Apparently the $600 million bailout was not enough.) The third bill, aimed at so-called “online harms”, would try to prevent people from saying hateful things to each other on social media.

This “online harms” bill is the scariest. Recently rebranded as the “online safety” bill, it’s apparently getting an overhaul from an expert panel and will be re-tabled in a few months. Let’s hope it never comes back. A version tabled last year, Bill C-36, would have created a tribunal wherein people found guilty of “online hate speech” could have been forced to pay up to $20,000 to their accusers, plus up to $50,000 in fines. In some cases, the accusers would be allowed to remain anonymous. Unlike the rarely used hate speech provisions in the Criminal Code, the tribunal would have only needed to find that the speech was hateful on a balance of probabilities, as opposed to the higher standard of beyond a reasonable doubt.

Even more ominously, C-36 would have allowed judges presented with “reasonable grounds” that a person might commit “an offence motivated by bias, prejudice or hate” in the future to threaten the would-be hater with up to 12 months in prison.

I don’t deny that hate speech can lead to harm. But do we really want government and judges deciding what crosses the line? One person’s hateful tweet is another person’s harsh but valuable contribution. Think J.K. Rowling. Think Dave Chapelle. Or think of the University of Toronto student who wrote recently that it was hateful for a professor to show an unflattering cartoon about Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, a man whose theocracy executes people for being gay.

Proponents of the bill will tell you that it only applies to the most extreme forms of vilification, but at the end of the day it means government-appointees deciding who gets to say what in an environment that financially incentivizes the aggrieved. People will self-censor even more than they already do.

March 28, 2022

QotD: The evolution of tanks through World War 2

One interesting thing about tank evolution that never gets mentioned in America is just how good the Soviets were at making tanks. The Germans are always assumed to have been the great tank builders, followed by the Americans, but it was the Russians who dominated the field in the tank game. Russian tanks were fast, powerful and easy to operate by their crews. Most important, they were reliable in all weather. The Russians assumed they would be fighting in horrible conditions and built a tank for it.

The Germans, in contrast, made one error after another when it came to tank design and tank building. They were obsessed with coming up with the biggest, most powerful tank, rather than making lots of good enough tanks. The result was lots of innovative designs, but most were failures and there was never enough of them. The Panzer IV was a very good tank with a platform that was flexible, but the Germans kept trying to come up with a super tank, rather than make lots of these. That was a costly error.

The American tank, which was used by the British, was not a great tank, but they were cheap and reliable, which meant there were loads of them. It was also a flexible platform for all sorts of other uses. The Sherman tank was about using the two advantages the Americans had over the Germans. One was more industry and the other was more soldiers. The plan was to beat the Germans with volume. While it would take five Sherman tanks to take out a German tank, that was math that worked in favor of the Americans.

This conflict between the perfect and the good enough showed up in many places during the war. The Germans seemed to look at the whole thing as an engineering project. The first step was to accept the restraints and then solve for the variables. The Russian and American view was always to limit the constraints and thereby increase the number of possible right answers. The Germans had much better human capital, but their opponents always had many more choices. They also had numbers, which counts for a lot.

The Z Man, “Tanking It”, The Z Blog, 2019-03-01.

March 25, 2022

Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow; Footage from its first flight

Polyus Studios

Published 7 Jul 2020Full documentary is still in development, enjoy the teaser!

(more…)

March 21, 2022

For some reason, Canadians’ interest in alternative currencies has risen substantially since February

I’m far from alone in taking the Canadian government’s absurd over-reaction to the Freedom Convoy 2022 political protest in February as a reason to be concerned about the Canadian banking system. Until then I’d paid very little attention to alternative currency options like Bitcoin and the like, but I now understand that they may be a key element in future financial planning. At Quillette, Jonathan Kay explains that he realized at the same time he needed to know much more about crypto:

“Bitcoin – from WSJ” by MarkGregory007 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

On February 15th, following weeks of anti-vaccine-mandate protests in downtown Ottawa, Justin Trudeau lurched from complete inaction to absurd overreaction by declaring a national emergency. One effect of this was that banks were suddenly authorized to freeze the personal assets of citizens linked with the protests, civil liberties be damned. Around the same time, moreover, hackers acquired and published identifying information associated with thousands of people who’d donated money to the protest movement. Rather than denounce this apparent criminal data breach, many public figures — including Gerald Butts, who’d been Trudeau’s right-hand man before resigning amid scandal in 2019 — actually celebrated this doxxing. Some media outlets even tried to mine the dox information for clickbait before being stung by a public backlash. While I hadn’t donated to the Freedom Convoy movement, I was sufficiently appalled by these developments that I started educating myself about how one might donate to a similar cause without government officials and social-media hyenas exploiting these transactions as a pretext to attack my assets and reputation.

The easiest way to get into the crypto market, I learned, is simply to open an account at an exchange platform such as Coinbase or Wealthsimple. But while they’re easy to use, exchange platforms also generally require clients to supply government-issued ID when they secure their accounts, and transactions are traceable by authorities. To assure myself of real anonymity and theft-protection, my tutor instructed me, a better (if more complex) option is “cold storage”. This is a real physical device — in my case, something called a Ledger — that acts as a personal crypto wallet.

My Ledger (which looks like a large USB key drive) contains the data required to generate the “private keys” (which look like long passwords, though that isn’t quite what they are) that allow me to send my crypto to other people. And that spending can be done only in those moments when the device is connected to the Internet, after which it can be relegated to a drawer or safe (thus the metaphorical concept of “cold storage”). On the other hand, I can receive money even if the Ledger is offline, so long as the sender has my public key, which (unlike a private key) is generally safe to give to others (such as, say, a prospective donor to any charitable cause that I might establish).

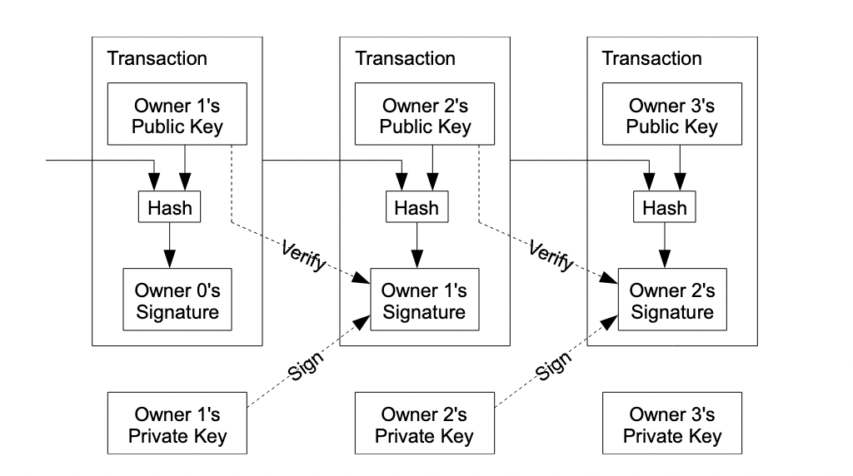

Bitcoin’s basic mechanics were set out in 2009 by the much-mythologized pseudonymous author (or collective) known as “Satoshi Nakamoto”. In a legendary white paper titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, Satoshi describes the newly conceived electronic coin as consisting of a chain of digital signatures (a blockchain) that build one upon the next through a mathematical mechanism known as a cryptographic hash function — a one-way function whose output doesn’t expose the original private key to reverse-engineering. So once a bitcoin transaction is recorded and added in verified form to the blockchain by everyone — this being the “public distributed ledger” that bitcoin users are part of — the transaction can’t be erased or reversed (with one important theoretical exception, described later on).

Image contained in Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, demonstrating the use of public and private keys to verify and sign bitcoin transactions.

Of course, you don’t need to understand how this cryptography works to use cryptocurrency. But it is worth getting your head around an important concept that fundamentally separates crypto from conventional assets such as, say, money that sits in a bank account. Your bank account number doesn’t have any value in and of itself: It’s just an institutional convenience that tells you and your bank where your actual money’s been filed (which is why that account number sits in plain sight on every physical check you sign, assuming you still use checks). But in the case of bitcoin, a private key basically is money — in the sense that anyone with access to such a key can spend the associated funds. And so if you lose your private-key information, or it gets stolen by a thief, there’s no 1-800 helpdesk number. It’s gone forever.

March 12, 2022

March 3, 2022

February 28, 2022

Hunting for books in the age of Amazon

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte remembers book searches before the internet got commercial:

“Beat Ground Zero San Francisco 2014” by Mobilus In Mobili is licensed under

Back in the late twentieth century, I used to build my vacations around book searches. Before going to any new town, I’d make a list of new and used bookstores and hit the best of them during my stay. There was a genuine excitement about entering each store: you never knew what you were going to find, and you were acutely aware that at any moment you might see something you’d never seen before or something you might never see again.

It was especially the fear of blowing that one chance of acquiring something special that turned me into a book hoarder. (I was never disciplined enough to be a collector; I only bought for my own use). Over the years, I accumulated tens of thousands of books. I’d rummage through them, once or twice a decade, and throw out the ones that no longer interested me to make room for new acquisitions. There were always new acquisitions, whether I was traveling or not.

Then came the internet and suddenly the whole concept of book scarcity blew up. Amazon had every new title one could want. I still go to my favorite bookstores when I travel — Daunt’s in London, Prairie Lights in Iowa City, Three Lives & Co. in Manhattan (the world’s most perfect small bookstore), Politics & Prose in DC, City Lights in San Francisco, The Last Bookstore in LA (further below), to name a few. I make the visits (none in the past two years) in part out of a sense of nostalgia for the waning era of brick-and-mortar, and also because well-curated shops often suggest books I might otherwise overlook.

Looking for books on vacation was always one of my habits, and before Amazon came along, I’d carefully search for bookstores along the route we’d be driving during our holiday and I rarely came back without a few armfuls of books. These days, especially since the era of lockdowns began, book stores are mostly just a memory … which is just as well in some sense because I have no disposable cash to spend on fripperies any more.

Of Ken’s list of favourite stores, I’ve only visited City Lights in San Francisco, back in early 1991. It was, bar none, the busiest bookstore I’d ever been in in my life. It rather felt like a record store (remember those?) on a big album release weekend than a staid, stodgy bookstore.

The internet also allowed used bookstores to put their wares online, and Bookfinder.com came along to organize their inventories. Bookfinder.com is a meta-search portal that allows book shoppers to scan the inventories of 100,000 booksellers at once. Type in a title and it will cough up an array of purchasing options: new, used, good condition, poor condition, former library copy, first edition, signed, etc. You compare editions and prices, make your choice, and click through to the bookseller’s site to finalize your purchase.

Bookfinder was launched by a Berkeley student named Anirvan Chatterjee in 1997, just a couple of years after Amazon was born. Chatterjee sold out to AbeBooks in 2005.

AbeBooks is a Canadian tech success story, originally operated out of Victoria by Rick & Vivian Pura and Keith & Cathy Waters. It is a digital marketplace that allows you to search the stock of a wide variety of established retailers. What differentiates it from Bookfinder is that you make your purchase right on the AbeBooks site. AbeBooks also sells the books it represents on other platforms, including eBay, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon. AbeBooks, in short, is a retail business while Bookfinder is a search tool.

AbeBooks was a dangerous discovery for me, and I bought a lot of books through them for a couple of years after discovering the service. Today, of course, not so much, especially as the shipping charges frequently run higher than the initial purchase price of the books themselves. Initially an independent service, AbeBooks is now owned by Amazon.

These days a lot of people want to shop for books anywhere but Amazon or its subsidiaries. For a non-Amazon version of AbeBooks you might try Alibris, founded by Martin Manley in California in 1997 (it’s been passed around to a range of venture capitalists and holding companies and is now in the hands of private investors). Biblio.com is another marketplace, serving mostly collectors. For non-Amazon alternatives to Bookfinder, viaLibri is a slick search tool that I only recently discovered, although it’s not quite as comprehensive as Bookfinder. Bookgilt is a good meta-search site for antiquarian and rare books. For new books, the best alternative to Bezos is your local bookstore, which can get you almost anything you need. See the map at the very bottom of this page or go to Bookshop.org or Indiebound.org. Or you can visit one of the chains, Chapters/Indigo or Barnes & Noble.

I still start most of my used book searches on Bookfinder. It’s old technology, Web 1.0, as hopelessly dated as the Drudge Report, but it works. I find it easy to navigate and it offers far more listings (and more information on each listing) than Amazon. I order from its smaller independents whenever practicable, although it’s often difficult to know exactly who you’re ordering from because the smaller shops are frequently represented on Bookfinder by their resellers, AbeBooks, Alibris, Amazon, and Biblio.

February 17, 2022

February 15, 2022

QotD: Breaking the trench stalemate with tanks

Where the Germans tried tactics, the British tried tools. If the problems were trenches, what was needed was a trench removal machine: the tank.

In theory, a good tank ought to be effectively immune to machine-gun fire, able to cross trenches without slowing and physically protect the infantry (who could advance huddled behind the mass of it), all while bringing its own firepower to the battle. Tracked armored vehicles had been an idea considered casually by a number of the pre-war powers but not seriously attempted. The British put the first serious effort into tank development with the Landship Committee, formed in February of 1915; the first real tanks, 49 British Mark I tanks, made their first battlefield appearance during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Reliability proved to be a problem: of the 49 tanks that stepped off on the attack on September 15th, only three were operational on the 16th, mostly due to mechanical failures and breakdowns.

Nevertheless there was promise in the idea that was clearly recognized and a major effort to show what tanks could do what attempted at Cambrai in November of 1917; this time hundreds of tanks were deployed and they had a real impact, breaking through the barbed wire and scattering the initial German defenses. But then came the inevitable German counter-attacks and most of the ground taken was lost. It was obvious that tanks had great potential; the French had by 1917 already developed their own, the light Renault FT tank, which would end up being the most successful tank of the war despite its small size (it is the first tank to have its main armament in a rotating turret and so in some sense the first “real” tank). This was hardly an under-invested-in technology. So did tanks break the trench stalemate?

No.

It’s understandable that many people have the impression that they did. Interwar armored doctrine, particularly German Maneuver Warfare (bewegungskrieg) and Soviet Deep Battle both aimed to use the mobility and striking power of tanks in concentrated actions to break the trench stalemate in future wars (the two doctrines are not identical, mind you, but in this they share an objective). But these were doctrines constructed around the performance capabilities of interwar tanks, particularly by two countries (Germany and the USSR) who were not saddled with large numbers of WWI era tanks (and so could premise their doctrine entirely on more advanced models). The Panzer II, with a 24.5mph top speed and an operational range of around 100 miles, depending on conditions, was actually in a position to race the train and win; the same of course true of the Soviet interwar T-26 light tank (19.3mph on roads, 81-150 mile operational range). Such tanks could have radios for coordination and communication on the move (something not done with WWI tanks or even French tanks in WWII).

By contrast, that Renault FT had a top speed of 4.3mph and an operational range of just 37 miles. The British Mark V tank, introduced in 1918, moved at only 5mph and had just 45 miles of range. Such tanks struggled to keep up with the infantry; they certainly were not going to win any race the infantry could not. It is little surprise that the French, posed with the doctrinal problem of having to make use of the many thousands of WWI tanks they had, settled on a doctrine whereby most tanks would simply be the armored gauntlet stretched over the infantry’s fist: it was all those tanks could do! The sort of tank that could do more than just dent the trench-lines (the same way a good infiltration assault with infantry could) were a decade or more away when the war ended.

Moreover, of course, the doctrine – briefly the systems of thinking and patterns of training, habit and action – to actually pull off what tanks would do in 1939 and 1940 were also years away. It seems absurd to fault World War I era commanders for not coming up with a novel tactical and operational system in 1918 for using vehicles that wouldn’t exist for another 15 years and yet more so assuming that they would get it right (since there were quite a number of different ideas post-war about how tanks ought to be used and while many of them seemed plausible, not all of them were practical or effective in the field). It is hard to see how any amount of support into R&D or doctrine was going to make tanks capable of breakthroughs even in the late 1920s or early 1930s (honestly, look at the “best” tanks of the early 1930s; they’re still not up to the task in most cases) much less by 1918.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part II: Breaking the Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-24.

February 14, 2022

Why SpaceX Cares About Dirt

Practical Engineering

Published 2 Nov 2021Why do structures big and small sink into the ground, and what can we do to stop it?

Before the so-called Starbase supported crazy test launches of the Starship spaceflight program, it was just a pile of dirt. After nearly two years, they hauled most of that soil back off the site for disposal. It might seem like a curious way to start a construction project, but foundations are critically important. Building that giant dirt pile was a clever way to prevent these facilities from sinking into the ground over time.

Practical Engineering is a YouTube channel about infrastructure and the human-made world around us. It is hosted, written, and produced by Grady Hillhouse. We have new videos posted regularly, so please subscribe for updates. If you enjoyed the video, hit that ‘like’ button, give us a comment, or watch another of our videos!

CONNECT WITH ME

____________________________________

Website: http://practical.engineering

Twitter: https://twitter.com/HillhouseGrady

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/practicalen…

Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/PracticalEng…

Patreon: http://patreon.com/PracticalEngineeringSPONSORSHIP INQUIRIES

____________________________________

Please email my agent at practicalengineering@standard.tvDISCLAIMER

____________________________________

This is not engineering advice. Everything here is for informational and entertainment purposes only. Contact an engineer licensed to practice in your area if you need professional advice or services. All non-licensed clips used for fair use commentary, criticism, and educational purposes.SPECIAL THANKS

____________________________________

This video is sponsored by Morning Brew.

Stock video and imagery provided by Getty Images, Shutterstock, and Videoblocks.

Tonic and Energy by Elexive is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6fBP…

Producer/Writer/Host: Grady Hillhouse

Assistant Producer: Wesley Crump

January 29, 2022

Viewing with alarm — Substack is a place where “misinformation is allowed to flourish”

Matt Taibbi posts, appropriately, on Substack about demands by others to force Substack to censor writers and their content:

Substack is home to tens of thousands of writers and over a million paying subscribers, quadruple last year’s total of 250,000. The sites range from newsletters for comics enthusiasts to crypto news to recipe ideas. Like the Internet as a whole, it’s basically a catalogue of everything.

Still, panic campaigns in legacy press consistently focus on handfuls of sites, and with impressive dishonesty describe them as representative. I was particularly struck by a recent Mashable article that talked about a supposed “backlash” against Substack’s “growing collection of anti-trans writers”, which seemed to refer to Jesse Singal (who is no such thing) and Graham Linehan and — that’s it. Substack is actually home to more trans writers than any other outlet, but to the Scolding Class, that’s not the point. The company’s real crime is that it refuses to submit to pressure campaigns and strike off Wrongthinkers.

Substack is designed to be difficult to censor. Because content is sent by email, it’s not easy to pressure platforms to zap offending material. It doesn’t depend on advertisers, so you can’t lean on them, either. The only real pressure points are company executives like Hamish McKenzie and Chris Best, who are now regular targets of these ham-fisted campaigns demanding they discipline writers.

The latest presents Substack as a place where, as Mashable put it, “COVID misinformation is allowed to flourish”. The objections mainly center around Joseph Mercola, Alex Berenson, and Robert Malone. There are issues with the specific critiques of each, but those aren’t the point. Every one of these campaigns revolves around the same larger problem: would-be censors misunderstanding the basic calculus of the freedom of speech.

Even in a society with fairly robust protections, as ours once was, the most dangerous misinformation is always, without exception, official.

As the old joke from the Cold War had it, never believe any rumour until it’s been officially denied.

Censors have a fantasy that if they get rid of all the Berensons and Mercolas and Malones, and rein in people like Joe Rogan, that all the holdouts will suddenly rush to get vaccinated. The opposite is true. If you wipe out critics, people will immediately default to higher levels of suspicion. They will now be sure there’s something wrong with the vaccine. If you want to convince audiences, you have to allow everyone to talk, even the ones you disagree with. You have to make a better case. The Substack people, thank God, still get this, but the censor’s disease of thinking there are shortcuts to trust is spreading.

January 26, 2022

Reliant Robin Three Wheeler | British Cars | Drive in (1973)

ThamesTv

Published 21 Jul 2019Tony Bastable takes the iconic Reliant Robin for a spin to see what this new British car has to offer.

First shown: 29/10/1973

If you would like to license a clip from this video please e mail:

archive@fremantle.com

Quote: VT8219

From the comments:

Tortinwall

2 years ago

I love the idea that you buy a Reliant Robin and then keep “valuable objects” in the boot.

January 14, 2022

Why Real Explosions Don’t Look Like Movie Explosions

Tom Scott

Published 8 Mar 2021Explosions on film are made to look good: fireballs and flame. In reality, though, they’re a bit disappointing. Here’s how Hollywood does it.

• Produced with an experienced, professional pyrotechnician. Do not attempt.

Thanks to Steve from Live Action FX: http://liveactionfx.com/

Filmed safely: https://www.tomscott.com/safe/

Camera: Simon Temple http://templefreelance.co.uk

Edited by Michelle Martin: https://twitter.com/mrsmmartinI’m at https://tomscott.com

on Twitter at https://twitter.com/tomscott

and on Instagram as tomscottgo