TimeGhost History

Published 23 Mar 2025In 1947, the British divide the Raj into two nations, India and Pakistan, triggering one of the deadliest mass migrations in history. Sectarian violence between Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims leaves at least 200,000 dead and displaces millions more. Hastily drawn borders turn neighbours into enemies. The partition’s bloody legacy will lead to decades of tension, war, and bloodshed.

(more…)

March 29, 2025

Why India and Pakistan Hate Each Other – W2W 015 – 1947 Q3

March 27, 2025

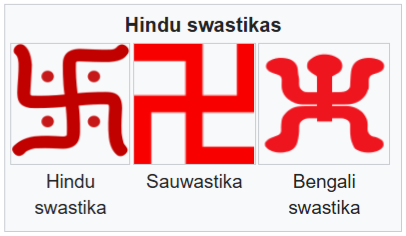

Ban the swastika? Are you some kind of racist?

In Ontario, the elected council for the Region of Durham has been reacting to a few painted swastika graffiti around the region over the last couple of months. To, as a politician might say, “send a message”, they proposed banning the use of the swastika altogether … failing to remember that it’s not just neo-Nazi wannabes who use it:

Durham council is adjusting the wording of its calls for a national ban on the Nazi swastika, or “Hakenkreuz“.

This follows efforts by religious advocates to distance their own symbols from the genocidal German fascist regime.

Swastikas often appear in Jain, Hindu and Buddhist iconography.

“The word ‘swastika’ means ‘well-being of all’,” explained Vijay Jain, president of Vishwa Jain Sangathan Canada, at Wednesday’s regional council meeting. “It’s a very sacred word. […] We use it extensively in our prayers.”

“Many Jain and Hindi parents give their children the name ‘Swastika’,” he added. “Many Hindi and Jain people, they keep their [business’s] name as ‘Swastika’. If you go to India, you’ll find the ‘Swastika’ name prominently used.”

“We stand in solidarity with the Jewish community and fully support all of the efforts by authorities to address growing antisemitism in Canada,” he said.

Regional council made its initial call for a ban on Nazi swastikas in February, after two separate incidents of the antisemitic symbol being scrawled inside a washroom at the downtown Whitby library.

On Wednesday, councillors voted to revise that motion to replace the word “swastika” with the term “Nazi symbols of hate”.

B’nai Brith Canada has been spearheading a petition campaign to have the Nazi symbol banned across the country.

The group has increasingly opted to refer to it by the alternative names “Nazi Hooked Cross” or “Hakenkreuz“.

On March 20, B’nai Brith put out a joint statement with Vishwa Jain Sangathan and other religious advocacy groups, calling for further differentiation between the symbols.

“These faiths’ sacred symbol (the Swastika) has been wrongfully associated with the Nazi Reich,” wrote Richard Robertson, B’nai Brith Canada’s Director of Research and Advocacy. “We must not allow the continued conflation of this symbol of peace with an icon of hate.”

March 20, 2025

The REAL Cause of the Revolutionary War

Atun-Shei Films

Published 15 Mar 2025What caused the American Revolution? Let’s dive beneath the surface-level understanding of British tyranny and unjust taxation and try to understand the long-term social, political, and economic forces which set the stage for our War of Independence.

00:00 Introduction

03:00 1. The World Turned Upside Down

13:50 2. The Paradox of American Liberalism

28:34 3. The Rage Militaire

38:12 Conclusion / Credits

(more…)

March 5, 2025

QotD: British and French Enlightenments

In 2005, [Gertrude Himmelfarb] published The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments. It is a provocative revision of the typical story of the intellectual era of the late eighteenth century that made the modern world. In particular, it explains the source of the fundamental division that still doggedly grips Western political life: that between Left and Right, or progressives and conservatives. From the outset, each side had its own philosophical assumptions and its own view of the human condition. Roads to Modernity shows why one of these sides has generated a steady progeny of historical successes while its rival has consistently lurched from one disaster to the next.

By the time she wrote, a number of historians had accepted that the Enlightenment, once characterized as the “Age of Reason”, came in two versions, the radical and the skeptical. The former was identified with France, the latter with Scotland. Historians of the period also acknowledged that the anti-clericalism that obsessed the French philosophes was not reciprocated in Britain or America. Indeed, in both the latter countries many Enlightenment concepts — human rights, liberty, equality, tolerance, science, progress — complemented rather than opposed church thinking.

Himmelfarb joined this revisionist process and accelerated its pace dramatically. She argued that, central though many Scots were to the movement, there were also so many original English contributors that a more accurate name than the “Scottish Enlightenment” would be the “British Enlightenment”.

Moreover, unlike the French who elevated reason to a primary role in human affairs, British thinkers gave reason a secondary, instrumental role. In Britain it was virtue that trumped all other qualities. This was not personal virtue but the “social virtues” — compassion, benevolence, sympathy — which British philosophers believed naturally, instinctively, and habitually bound people to one another. This amounted to a moral reformation.

In making her case, Himmelfarb included people in the British Enlightenment who until then had been assumed to be part of the Counter-Enlightenment, especially John Wesley and Edmund Burke. She assigned prominent roles to the social movements of Methodism and Evangelical philanthropy. Despite the fact that the American colonists rebelled from Britain to found a republic, Himmelfarb demonstrated how very close they were to the British Enlightenment and how distant from French republicans.

In France, the ideology of reason challenged not only religion and the church, but also all the institutions dependent upon them. Reason was inherently subversive. But British moral philosophy was reformist rather than radical, respectful of both the past and present, even while looking forward to a more enlightened future. It was optimistic and had no quarrel with religion, which was why in both Britain and the United States, the church itself could become a principal source for the spread of enlightened ideas.

In Britain, the elevation of the social virtues derived from both academic philosophy and religious practice. In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith, the professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow University, was more celebrated for his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) than for his later thesis about the wealth of nations. He argued that sympathy and benevolence were moral virtues that sprang directly from the human condition. In being virtuous, especially towards those who could not help themselves, man rewarded himself by fulfilling his human nature.

Edmund Burke began public life as a disciple of Smith. He wrote an early pamphlet on scarcity which endorsed Smith’s laissez-faire approach as the best way to serve not only economic activity in general but the lower orders in particular. His Counter-Enlightenment status is usually assigned for his critique of the French Revolution, but Burke was at the same time a supporter of American independence. While his own government was pursuing its military campaign in America, Burke was urging it to respect the liberty of both Americans and Englishmen.

Some historians have been led by this apparent paradox to claim that at different stages of his life there were two different Edmund Burkes, one liberal and the other conservative. Himmelfarb disagreed. She argued that his views were always consistent with the ideas about moral virtue that permeated the whole of the British Enlightenment. Indeed, Burke took this philosophy a step further by making the “sentiments, manners, and moral opinion” of the people the basis not only of social relations but also of politics.

Keith Windschuttle, “Gertrude Himmelfarb and the Enlightenment”, New Criterion, 2020-02.

March 3, 2025

QotD: Arguments around “spontaneous order” and “divine intervention”

A libertarian economist I read fairly often once noted that he found it interesting that many people on the political left who believe in natural selection without any kind of guidance cannot accept the idea that economical order can arise without their guidance. And, likewise, many on the right are completely comfortable with spontaneous order in free markets but can’t conceive of it in the natural world.

It seems to me that this is a bit like the old “irresistible force versus immovable object” paradox. On the one hand, the universe, life, human life, seem impossibly complex to have happened randomly. On the other hand, the universe is actually very large. Perhaps there are enough monkeys banging away at typewriters to produce not just Shakespeare, but the script of every Seinfeld episode.

Esteban, “Evolution, Economies And Spontaneous Order”, Continental Telegraph, 2020-01-22.

February 25, 2025

QotD: Identity politics as a secular religion

Tom Holland, in his book Dominion, The making of the Western Mind, identifies the “trace elements” of Christianity in the woke world. The example he used was the intersectional feminists in the #MeToo movement offering white feminists the chance to “acknowledge their own entitlement, to confess their sins and to be granted absolution”.

But the problem with identity politics as a secular religion is precisely its failure to allow for absolution. The faith that Saad espouses is utterly bleak, even cloaked as it is in words of love. It utterly fails to allow for redemption, and its most direct religious antecedent is found in Calvinist predestination.

Under this doctrine, God has predetermined whether you are damned or elect. From the second that the right sperm hit it lucky with the most fecund egg, your place in the woke hierarchy was decided. In the modern progressive world, informed by intersectional feminists, it does not matter what you say or do, the only defining factor in your state of grace is your skin, gender and sexuality.

This is a profoundly depressing outlook for three main reasons. The first is the essential nihilism in the creed. Your intent? Irrelevant. Your deeds? Likewise. The sum of your experience, desires, longings, beliefs? Your humanity itself? Nah, not relevant.

The second dispiriting message is that the problems its aims to address are insoluble. White people are racist by their nature, and inherently incapable of seeing their own racism or addressing it. Men are misogynists, by default, witting or unwitting bulwarks of the patriarchy. If they don’t believe they are individually at fault they are in denial. And if they try to say, actually, I’m not sure the patriarchy exists, they are mansplaining misogynist bastards. This is the politics of perpetual antagonism, of a kind of bleak acceptance that all relationships between different categories of human are necessarily fractious.

[…]

The third problem with Puritan wokeness is that it [has] sinister echoes in the history of predestination. When the creed reached its zenith in the seventeenth century, the logical hole at its centre became insanely obvious. If it does not matter to God how you behave, because your salvation was pre-determined at birth, why not behave however the hell you want to?

Antonia Senior, “Identity politics is Christianity without the redemption”, UnHerd, 2020-01-20.

February 16, 2025

Pope Fights: The Pornocracy – Yes it’s really called that

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 25 Oct 2024Guard your browsing histories, the Popes are at it again …

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Rome: A History in Seven Sackings by Matt Kneale

Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy by John Julius Norwich

Antapodosis by Liutprand of Cremona

A. Burt Horsley, “Pontiffs, Palaces and Pornocracy — A Godless Age”, in Peter and the Popes (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 65–78.

(more…)

February 14, 2025

Henry VIII, Lady Killer – History Hijinks

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 3 Feb 2023brb I’m blaring “Haus of Holbein” from Six the Musical on the loudest speakers I own.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Britannica “Henry VIII” (https://www.britannica.com/biography/…, History “Who Were The Six Wives of Henry VIII” (https://www.history.com/news/henry-vi…), The Great Courses lectures: “Young King Hal – 1509-27”, “The King’s Great Matter – 1527-30”, “The Break From Rome – 1529-36”, “A Tudor Revolution – 1536-47”, and “The Last Years of Henry VIII – 1540-47” from A History of England from the Tudors to the Stuarts by Robert Bucholz

(more…)

February 6, 2025

January 14, 2025

QotD: Ritual in medieval daily life

I am not in fact claiming that medieval Catholicism was mere ritual, but let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that it was — that so long as you bought your indulgences and gave your mite to the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever and showed up and stayed awake every Sunday as the priest blathered incomprehensible Latin at you, your salvation was assured, no matter how big a reprobate you might be in your “private” life. Despite it all, there are two enormous advantages to this system:

First, n.b. that “private” is in quotation marks up there. Medieval men didn’t have private lives as we’d understand them. Indeed, I’ve heard it argued by cultural anthropology types that medieval men didn’t think of themselves as individuals at all, and while I’m in no position to judge all the evidence, it seems to accord with some of the most baffling-to-us aspects of medieval behavior. Consider a world in which a tag like “red-haired John” was sufficient to name a man for all practical purposes, and in which even literate men didn’t spell their own names the same way twice in the same letter. Perhaps this indicates a rock-solid sense of individuality, but I’d argue the opposite — it doesn’t matter what the marks on the paper are, or that there’s another guy named John in the same village with red hair. That person is so enmeshed in the life of his community — family, clan, parish, the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever — that “he” doesn’t really exist without them.

Should he find himself away from his village — maybe he’s the lone survivor of the Black Death — then he’d happily become someone completely different. The new community in which he found himself might start out as “a valley full of solitary cowboys”, as the old Stephen Leacock joke went — they were all lone survivors of the Plague — but pretty soon they’d enmesh themselves into a real community, and red-haired John would cease to be red-haired John. He’d probably literally forget it, because it doesn’t matter — now he’s “John the Blacksmith” or whatever. Since so many of our problems stem from aggressive, indeed overweening, assertions of individuality, a return to public ritual life would go a long way to fixing them.

The second huge advantage, tied to the first, is that community ritual life is objective. Maybe there was such a thing as “private life” in a medieval village, and maybe “red-haired John” really was a reprobate in his, but nonetheless, red-haired John performed all his communal functions — the ones that kept the community vital, and often quite literally alive — perfectly. You know exactly who is failing to hold up his end in a medieval village, and can censure him for it, objectively — either you’re at mass or you’re not; either you paid your tithe or you didn’t; and since the sacrament of “confession” took place in the open air — Cardinal Borromeo’s confessional box being an integral part of the Counter-Reformation — everyone knew how well you performed, or didn’t, in whatever “private” life you had.

Take all that away, and you’ve got process guys who feel it’s their sacred duty — as in, necessary for their own souls’ sake — to infer what’s going on in yours. Strip away the public ritual, and now you have to find some other way to make everyone’s private business public … I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Calvinism is really Karen-ism, and if it IS unfair, I don’t care, because fuck Calvin, the world would’ve been a much better place had he been strangled in his crib.

A man is only as good as the public performance of his public duties. And, crucially, he’s no worse than that, either. Since process guys will always pervert the process in the name of more efficiently reaching the outcome, process guys must always be kept on the shortest leash. Send them down to the countryside periodically to reconnect with the laboring masses …

Severian, “Faith vs. Works”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-07.

December 25, 2024

QotD: Divine will

It is only the savage, whether of the African bush or of the American gospel tent, who pretends to know the will and intent of God exactly and completely.

H.L. Mencken, Damn! A Book of Calumny, 1918.

December 19, 2024

“A decree went out from Caesar Augustus” – The evidence for the date of the birth of Jesus

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 18 Dec 2024It’s December, with Christmas fast approaching, and I suspect that a fair few people who never think much about the Romans will hear mention of Caesar Augustus because of this verse from Luke’s Gospel. I have an appendix about this in my biography of Augustus, so thought that I would talk about how the New Testament dates the Christmas story and how well this fits with our other sources for the Ancient World.

November 23, 2024

QotD: Nietzsche’s message

[Nietzsche’s] objection to Christianity is simply that it is mushy preposterous, unhealthy, insincere, enervating. It lays its chief stress, not upon the qualities of vigorous and efficient men, but upon the qualities of the weak and parasitical. True enough, the vast majority of men belong to the latter class: they have very little enterprise and very little courage. For these Christianity is good enough. It soothes them and heartens them; it apologizes for their vegetable existence; it fills them with an agreeable sense of virtue. But it holds out nothing to the men of the ruling minority; it is always in direct conflict with their vigor and enterprise; it seeks incessantly to weaken and destroy them. In consequence, Nietzsche urged them to abandon it. For such men he proposed a new morality — in his own phrase, a “transvaluation of values” — with strength as its highest good and renunciation as its chiefest evil. They waste themselves to-day by pulling against the ethical stream. How much faster they would go if the current were with them! But as I have said — and it cannot be repeated too often — Nietzsche by no means proposed a general repeal of the Christian ordinances. He saw that they met the needs of the majority of men, that only a small minority could hope to survive without them. In the theories and faiths of this majority he has little interest. He was content to have them believe whatever was most agreeable to them. His attention was fixed upon the minority. He was a prophet of aristocracy. He planned to strike the shackles from the masters of the world …

H.L. Mencken, “Transvaluation of Morals”, The Smart Set, 1915-03.

November 19, 2024

QotD: The Reformation

The Reformation’s great complaint against the late-medieval Church is that it, the Church, had turned Catholicism entirely into a process. Those naive folks who argue that life wasn’t so hard for the medieval peasant because he had all those days off — 180 some odd saints’ days, feast days, and so on — have a bit of a point for all that. Ritual life simply was community life; “free time” as we understand it just wasn’t a thing in the middle ages, and not just because life was such a constant struggle. Every hour of your day carried its obligation to someone; there’s a reason the very best sources for “daily life in the middle ages” are called books of hours.

Your hotter Protestants, your John Calvins and Oliver Cromwells and so on, saw all of this as mere ritual. And to be fair to them, late-medieval Catholicism was very elaborate, and very, very weird — slog through a few chapters of The Stripping of the Altars if you want the details. To the Prods, this was cheating — you can’t just go through the motions and expect to get into Heaven. They made a similar distinction between “natural magic” and the unlawful stuff — the one was undertaken only after deep study and the most rigorous self-purification, while the other “worked” entirely mechanically, because what the sorcerer was really doing was cheating; he was really making a deal with a (or The) devil, to short-circuit the natural processes.

Now, it’s important to realize that the Protestants were not saying anything close to “do your own thing, man”. They were NOT hippies, encouraging everyone to read the Bible and decide for themselves how best to commune with the Big JC. The German peasants thought that’s what Martin Luther was saying back in 1524, but Luther himself was out there urging the authorities to smash the peasants with extreme prejudice. The Protestants were, in fact, extremely concerned about ritual. It just had to be the right ritual, the Biblically sanctioned ritual, and nothing but that — that’s what “Puritanism” (originally an insult) means.

Severian, “Faith vs. Works”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-07.

November 14, 2024

Early Christianity – from ~1,000 to 40 million believers in the Roman Empire

The latest book review at Astral Codex Ten is Rodney Stark’s The Rise of Christianity:

The rise of Christianity is a great puzzle. In 40 AD, there were maybe a thousand Christians. Their Messiah had just been executed, and they were on the wrong side of an intercontinental empire that had crushed all previous foes. By 400, there were forty million, and they were set to dominate the next millennium of Western history.

Imagine taking a time machine to the year 2300 AD, and everyone is Scientologist. The United States is >99% Scientologist. So is Latin America and most of Europe. The Middle East follows some heretical pseudo-Scientology that thinks L Ron Hubbard was a great prophet, but maybe not the greatest prophet.

This can only begin to capture how surprised the early Imperial Romans would be to learn of the triumph of Christianity. At least Scientology has a lot of money and a cut-throat recruitment arm! At least they fight back when you persecute them! At least they seem to be in the game!

Rodney Stark was a sociologist of religion. He started off studying cults, and got his big break when the first missionaries of the Unification Church (“Moonies”) in the US let him tag along and observe their activities. After a long and successful career in academia, he turned his attention to the greatest cult of all and wrote The Rise Of Christianity. He spends much of it apologizing for not being a classical historian, but it’s fine — he’s obviously done his homework, and he hopes to bring a new, modern-religion-informed perspective to the ancient question.

So: how did early Christianity win?