Sea Lord Mountbatten

Published 14 Jul 2024Hey guys! Today I am happy to bring you guys Jutland! Our cinematic on the 1916 Naval Battle of Jutland! Enjoy!

(more…)

April 5, 2025

World of Warships – Battle Of Jutland

January 19, 2025

January 11, 2025

QotD: “Composite” pre-gunpowder infantry units

I should be clear I am making this term up (at least as far as I know) to make a contrast between what Total War has, which are single units made up of soldiers with identical equipment loadouts that have a dual function (hybrid infantry) and what it doesn’t have: units composed of two or more different kinds of infantry working in concert as part of a single unit, which I am going to call composite infantry.

This is actually a very old concept. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-609 BC) is one of the earliest states where we have pretty good evidence for how their infantry functioned – there was of course infantry earlier than this, but Bronze Age royal records from Egypt, Mesopotamia or Anatolia tend to focus on the role of elites who, by the late Bronze Age, are increasingly on chariots. But for the early Iron Age Neo-Assyrian empire, the fearsome effectiveness of its regular (probably professional) infantry, especially in sieges, was a key component of its foreign-policy-by-intimidation strategy, so we see a lot more of them.

That infantry was split between archers and spear-and-shield troops, called alternately spearmen (nas asmare) or shield-bearers (sab ariti). In Assyrian artwork, they are almost always shown in matched pairs, each spearman paired off with a single archer, physically shielding the archer from attack while the archer shoots. The spearmen are shown with one-handed thrusting spears (of a fairly typical design: iron blade, around 7 feet long) and a shield, either a smaller round shield or a larger “tower” shield. Assyrian records, meanwhile, reinforce the sense that these troops were paired off, since the number of archers and spearmen typically match perfectly (although the spearmen might have subtypes, particularly the “Qurreans” who may have been a specialist type of spearman recruited from a particular ethnic group; where the Qurreans show up, if you add Qurrean spearmen to Assyrian spearmen, you get the number of archers). From the artwork, these troops seem to have generally worked together, probably lined up in lines (in some cases perhaps several pairs deep).

The tactical value of this kind of composite formation is obvious: the archers can develop fire, while the spearmen provide moving cover (in the form of their shields) and protection against sudden enemy attack by chariot or cavalry with their spears. The formation could also engage in shock combat when necessary; the archers were at least sometimes armored and carried swords for use in close combat and of course could benefit (at least initially) from the shields of the front rank of spearmen.

The result was self-shielding shock-capable foot archer formations. Total War: Warhammer also flirts with this idea with foot archers who have their own shields, but often simply adopts the nonsense solution of having those archers carry their shields on their backs and still gain the benefit of their protection when firing, which is not how shields work (somewhat better are the handful of units that use their shields as a firing rest for crossbows, akin to a medieval pavisse).

We see a more complex version of this kind of composite infantry organization in the armies of the Warring States (476-221 BC) and Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) periods in China. Chinese infantry in this period used a mix of weapons, chiefly swords (used with shields), crossbows and a polearm, the ji which had both a long spearpoint but also a hook and a striking blade. In Total War: Three Kingdoms, which represents the late Han military, these troop-types are represented in distinct units: you have a regiment of ji-polearm armed troops, or a regiment of sword-and-shield troops, or a regiment of crossbowmen, which maneuver separately. So you can have a block of polearms or a block of crossbowmen, but you cannot have a mixed formation of both.

Except that there is a significant amount of evidence suggesting that this is exactly how the armies of the Han Dynasty used these troops! What seems to have been common is that infantry were organized into five-man squads with different weapon-types, which would shift their position based on the enemy’s proximity. So against a cavalry or chariot charge, the ji might take the front rank with heavier crossbows in support, while the sword-armed infantry moved to the back (getting them out of the way of the crossbows while still providing mass to the formation). Of course against infantry or arrow attack, the swordsmen might be moved forward, or the crossbowmen or so on (sometimes there were also spearmen or archers in these squads as well). These squads could then be lined up next to each other to make a larger infantry formation, presenting a solid line to the enemy.

(For more on both of these military systems – as well as more specialist bibliography on them – see Lee, Waging War (2016), 89-99, 137-141.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collection: Total War‘s Missing Infantry-Type”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-01.

December 16, 2024

QotD: Movie and video game portrayals of generalship in pre-modern armies

As we’ll see, in a real battle when seconds count, new orders are only a few minutes away. Well, sometimes they’re rather more than a few minutes away. Or not coming at all.

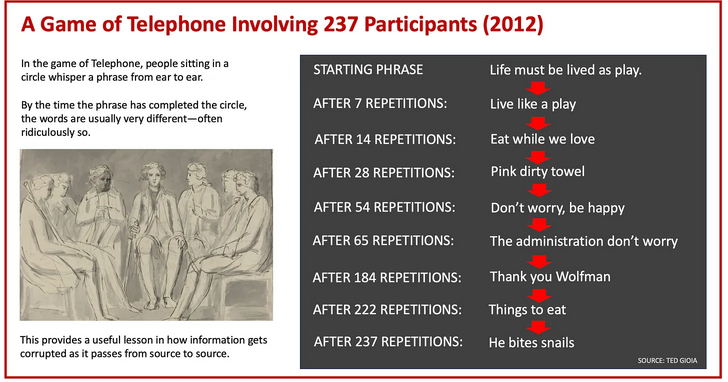

This is also true, of course, in films. Our friend Darius III from Alexander (2004) silently waves his hand to mean “archers shoot!” and also “chariots, charge!” and then also “everyone else, charge!” Keeping in mind what we saw about the observation abilities of a general on horseback, you can well imagine how able Darius’ soldiers will have been to see his hand gestures while they were on foot from a mile or so away. Yet his army responds flawlessly to his silent arm-gestures. Likewise the flag-signalling in Braveheart‘s (1995) rendition of the Battle of Falkirk: a small banner, raised in the rear is used to signal to soldiers who are looking forward at the enemy, combined with a fellow shouting “advance”. One is left to assume that these generals control their armies in truth through telepathy.

There is also never any confusion about these orders. No one misinterprets the flag or hears the wrong orders. Your unit commanders in Total War never ignore or disobey you; sure the units themselves can rout, but you never have a unit in good order simply ignore your orders – a thing which happened fairly regularly in actual battles! Instead, units are unfailingly obedient right up until the moment they break entirely. You can order untrained, unarmored and barely armed pitchfork peasant levies to charge into contact with well-ordered plate-clad knights and they will do it.

The result is that battleplans in modern strategy games are often impressive intricate, involving the player giving lots of small, detailed orders (sometimes called “micro”, short for “micromanagement”) to individual units. It is not uncommon in a Total War battle for a player to manually coordinate “cycle-charges” (having a cavalry unit charge and retreat and then charge the same unit again to abuse the charge-bonus mechanics) while also ordering their archers to focus fire on individual enemy units while simultaneously moving up their own infantry reserves in multiple distinct maneuvering units to pin dangerous enemy units while also coordinating the targeting of their field artillery. Such attacks in the hands of a skilled player can be flawlessly coordinated because in practice the player isn’t coordinating with anyone but themselves.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Total Generalship: Commanding Pre-Modern Armies, Part II: Commands”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-06-03.

November 17, 2024

November 16, 2024

The 1980 Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Tournament

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander starts a post titled “The Early Christian Strategy” with some relevant back-story (fore-story?) involving game theory and the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma:

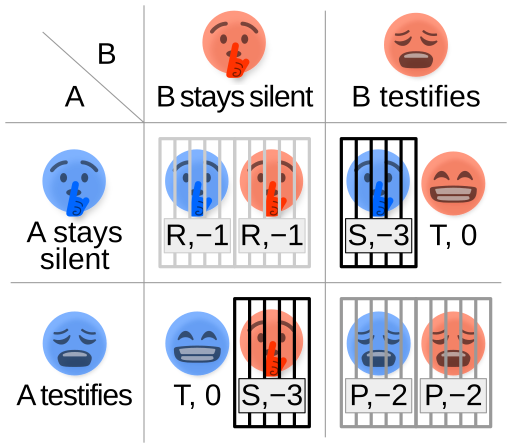

In 1980, game theorist Robert Axelrod ran a famous Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Tournament.

He asked other game theorists to send in their best strategies in the form of “bots”, short pieces of code that took an opponent’s actions as input and returned one of the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma outputs of COOPERATE or DEFECT. For example, you might have a bot that COOPERATES a random 80% of the time, but DEFECTS against another bot that plays DEFECT more than 20% of the time, except on the last round, where it always DEFECTS, or if its opponent plays DEFECT in response to COOPERATE.

In the “tournament”, each bot “encountered” other bots at random for a hundred rounds of Prisoners’ Dilemma; after all the bots had finished their matches, the strategy with the highest total utility won.

To everyone’s surprise, the winner was a super-simple strategy called TIT-FOR-TAT:

- Always COOPERATE on the first move.

- Then do whatever your opponent did last round.

This was so boring that Axelrod sponsored a second tournament specifically for strategies that could displace TIT-FOR-TAT. When the dust cleared, TIT-FOR-TAT still won — although some strategies could beat it in head-to-head matches, they did worst against each other, and when all the points were added up TIT-FOR-TAT remained on top.

In certain situations, this strategy is dominated by a slight variant, TIT-FOR-TAT-WITH-FORGIVENESS. That is, in situations where a bot can “make mistakes” (eg “my finger slipped”), two copies of TIT-FOR-TAT can get stuck in an eternal DEFECT-DEFECT equilibrium against each other; the forgiveness-enabled version will try cooperating again after a while to see if its opponent follows. Otherwise, it’s still state-of-the-art.

The tournament became famous because – well, you can see how you can sort of round it off to morality. In a wide world of people trying every sort of con, the winning strategy is to be nice to people who help you out and punish people who hurt you. But in some situations, it’s also worth forgiving someone who harmed you once to see if they’ve become a better person. I find the occasional claims to have successfully grounded morality in self-interest to be facile, but you can at least see where they’re coming from here. And pragmatically, this is good, common-sense advice.

For example, compare it to one of the losers in Axelrod’s tournament. COOPERATE-BOT always cooperates. A world full of COOPERATE-BOTS would be near-utopian. But add a single instance of its evil twin, DEFECT-BOT, and it folds immediately. A smart human player, too, will easily defeat COOPERATE-BOT: the human will start by testing its boundaries, find that it has none, and play DEFECT thereafter (whereas a human playing against TIT-FOR-TAT would soon learn not to mess with it). Again, all of this seems natural and common-sensical. Infinitely-trusting people, who will always be nice to everyone no matter what, are easily exploited by the first sociopath to come around. You don’t want to be a sociopath yourself, but prudence dictates being less-than-infinitely nice, and reserving your good nature for people who deserve it.

Reality is more complicated than a game theory tournament. In Iterated Prisoners’ Dilemma, everyone can either benefit you or harm you an equal amount. In the real world, we have edge cases like poor people, who haven’t done anything evil but may not be able to reciprocate your generosity. Does TIT-FOR-TAT help the poor? Stand up for the downtrodden? Care for the sick? Domain error; the question never comes up.

Still, even if you can’t solve every moral problem, it’s at least suggestive that, in those domains where the question comes up, you should be TIT-FOR-TAT and not COOPERATE-BOT.

This is why I’m so fascinated by the early Christians. They played the doomed COOPERATE-BOT strategy and took over the world.

October 8, 2024

QotD: The competitive instinct

I once saw an interview with basketball player Charles Barkley, in which he discussed his retirement. Barkley was a Hall of Fame player, and like most of those guys, he hung on a few seasons too long. Even having lost a step or three, Sir Charles was still a decent player, but that’s all he was — a decent player, but getting paid like a superstar and with a superstar’s reputation. A few seasons after retiring, he admitted as much. He said something like (from memory) “I’d guard a guy and think, ‘this is going to be easy, this guy is terrible’. And then he’d beat me, and I’d realize I just got beat by some guy who’s terrible, and then I knew it was time to hang it up.”

One thing chicks of both sexes and all however-many-we’re-up-to genders don’t realize these days is how competitive men — actual biological males — are hardwired to be. Things like World of Warcraft and fantasy football only exist because the genius who invented those figured out a way to tap into that heretofore-unexpressed male competitiveness. And indeed, it’s the guy who’d never even dream of putting on shoulder pads who’s the most insanely competitive guy in a fantasy football league or (I’m certain) a whatever-they’re-called in World of Warcraft. Even the uber-dorks in the Math Club and the Speech and Debate Society went after each other like Mickey Ward and Arturo Gatti. It’s just how guys are … or, at least, how guys used to be.

[…]

When it comes right down to it, that’s why men of a certain age simply don’t get “women’s sports”. Few will be as crustily chauvinistic as yer ‘umble narrator, and come right out and say it, but here goes: Women’s “sports” are just a shoddy knockoff of the real thing, because women just aren’t wired that way. That’s not to say that there aren’t competitive women, or athletic women — obviously there are, some very athletic and very competitive — but the female of the species just isn’t wired to put in the work the way males are. When faced with the prospect of three straight hours in the batting cage, swinging at curve after curve until your blisters have blisters and your shoulders feel like they’re falling out of their sockets, most women will quite sensibly ask “why bother?” Competition-for-competition’s-sake, even when it’s only against yourself in those long, long, looooong hours in the cage, just doesn’t motivate them the way it does us.

Which is why a person’s reaction to Simone Biles, or the USA Women’s soccer team, or the WNBA, or what have you is an almost perfect predictor of their age, not just their “gender”. I judge sports as sports. I don’t care about soccer, but if I did, I’d care about it as soccer — meaning, I’d want to see the best possible players, playing at the highest possible level. Women’s Olympic teams — that is to say, all star teams, the very best players — routinely get smoked by teams of 15 year old boys. Sir Charles is pushing sixty, but he could dominate the WNBA right now, in street clothes. Obviously this doesn’t apply to Pee Wee or rec leagues, but if you’re going to take a paycheck for doing it, then I want to see exactly what I paid for.

In estrogen-drenched, synchronized-ovulation Clown World, it’s all about appearances. Sure, she let her team down and wussed out (while still talking up how great she is), but can’t you see that it gave her the sadz? Sure, Megan Rapinoe et al keep getting smoked by 14 year old boys, then choking in international competition, but can’t you see her out there, with her pink hair and her tats and her Strong, Confident Empowerment? The “competition”, such as it is, is an excuse for the display. Michael Jordan ought to give baseball another shot. We know he can cry. These days, that’d get him a first-class ticket to Cooperstown.

Severian, “On Competition”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-08-02.

September 17, 2024

QotD: “Megacorporations” in history and fiction

I think it is worth stressing here, even in our age of massive mergers and (at least, before the pandemic) huge corporate profits, just how vast the gap in resources is between large states and the largest companies. The largest company by raw revenue in the world is Walmart; its gross revenue (before expenses) is around $525bn. Which sounds like a lot! Except that the tax revenue of its parent country, the United States, was $3.46 trillion (in 2019). Moreover, companies have to go through all sorts of expenses to generate that revenue (states, of course, have to go about collecting taxes, but that’s far cheaper; the IRS’s operating budget is $11.3bn, generating a staggering 300-fold return on investment); Walmart’s net income after the expenses of making that money is “only” $14.88bn. If Walmart focused every last penny of those returns into building a private army then after a few years of build-up, it might be able to retain a military force roughly on par with … the Netherlands ($12.1bn); the military behemoth that is Canada ($22.2bn US) would still be solidly out of reach. And that’s the largest company in the world!

And that data point brings us to our last point – and the one I think is most relevantly applicable for speculative fiction megacorporations – historical megacorporations (by which I mean “true” megacorps that took on major state functions over considerable territory, which is almost always what is meant in speculative fiction) are products of imperialism, produced by imperial states with limited state capacity “outsourcing” key functions of imperial rule to private entities. And that explains why it seems that, historically, megacorporations don’t dominate the states that spawn them: they are almost always products and administrative arms of those states and thus still strongly subordinate to them.

I think that incorporating that historical reality might actually create storytelling opportunities if authors are willing to break out of the (I think quite less plausible) paradigm of megacorporations dominating the largest and most powerful communities that appear so often in science fiction. What if, instead of a corporate-dominated Earth (or even a corp-dominated Near-Future USA), you set a story in a near-future developing country which finds itself under the heel of a megacorporation that is essentially an arm of a foreign government, much like the EIC and VOC? Of course that would mean leavening the anti-capitalist message implicit in the dystopian megacorporation with an equally skeptical take about the utility of state power (it has always struck me that while speculative fiction has spent decades warning about the dangers of capitalist-corporate-power, the destructive potential of state power continues to utterly dwarf the damage companies do. Which is not to say that corporations do no damage of course, only that they have orders of magnitude less capability – and proven track record – to do damage compared to strong states).

(And as an aside, I know you can make an argument that Cyberpunk 2077 does actually adopt this megacorporation-as-colonialism framing, but that’s simply not how the characters in the game world think about or describe Arasoka – the biggest megacorp – which, in any event, appears to have effectively absorbed its home-state anyway. Arasoka isn’t an agent of the Japanese government, it is rather a global state in its own right and according to the lore has effectively controlled its home government for almost a century by the time of the game.)

In any event, it seems worth noting that the megacorporation is not some strange entity that might emerge in the far future with some sort of odd and unpredictable structure, but instead is a historical model of imperial governance that has existed in the past and (one may quibble here with definitions) continues to exist in the present. And, frankly, the historical version of this unusual institution is both quite different from the dystopian warnings of speculative fiction, but also – I think – rather more interesting.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: January 1, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-01.

August 20, 2024

German magazine Der Spiegel warns about “The Secret Hitlers” of the far right who threaten western civilization

The spectre of Hitlerian fascism looms over the western world once again, but Der Spiegel won’t take this threat lying down:

“How Fascism Begins”: The present cover of Der Spiegel, depicting Björn Höcke, Marine le Pen and Donald Trump as the new fascists. Establishment German hysteria about “the right” is now achieving an intensity to rival American hysteria about race during the Summer of Floyd.

Hitler is not like other mortals; he may not really be dead, and his spirit is likely to return at any moment. Perhaps it already has. This is why our foremost news magazine, Der Spiegel, chose this image to head their cover story on “The Secret Hitlers“, a bizarre opus of current-year political lunacy penned by Lothar Gorris and Tobias Rapp.

“Is fascism returning?” Gorris and Rapp want to know. “Or is it already here, in the form of [Donald] Trump, [Viktor] Orbán [or Björn] Höcke? And if so, could it disappear again?” What follows, they explain, is “an attempt to identify evil”.

This is the kind of insanity that comes over you when you elevate establishment political ideology into a civic religion. You reduce the entire project of state politics to a dubious exercise in piety, where the aim is not to achieve good outcomes or develop pragmatic solutions, but to engage in moral peacockery. For the Gorrises and the Rapps of our discourse, the greatest problem facing the liberal faithful of the Federal Republic is not mass migration, deindustrialisation, soon-to-be-insolvent pension programmes or the overblown state entitlement system, oh no. It is finding and rooting out mythological political demons and preventing the second coming of the secular antichrist.

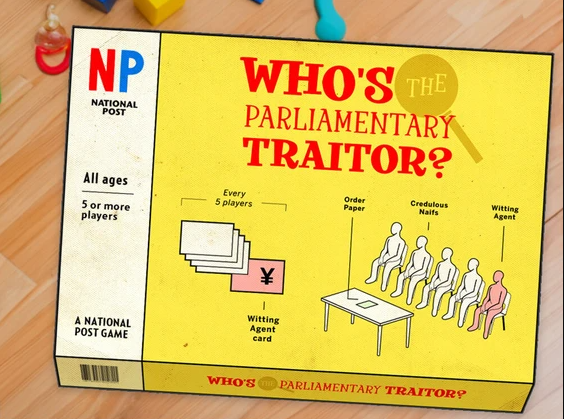

Gorris and Rapp (for convenience, I will refer to these feeble-minded men henceforth as Grapp) open with an extended anecdote about a 2016 board game called Secret Hitler.

The setting is the year 1932, the Reichstag in Berlin. The players are divided into two groups: Fascists and Democrats, with the Democrats making up the majority, which sounds familiar. The Fascists have a decisive advantage at the start: they know who the other Fascists are, which also reflects the truth in the history books. The Democrats don’t have this information; every other player could be friend or foe. The fascists win the game if they get six laws through the Reichstag or if Hitler is elected Chancellor. To win, the Democrats must pass five laws or expose and kill Hitler.

The basic premise of the game is that everyone pretends to be democrats. In truth, the real democrats would only have to trust each other and the fascists wouldn’t stand a chance. But it’s not that simple, because sometimes the democrats have to vote in favour of a fascist law for lack of options and therefore fall under suspicion of fascism. Which is exactly what the fascists want.

One realisation: there is no guarantee of the right strategy that will ultimately see the good guys win and the bad guys lose. One wrong decision that feels right, and Hitler is Reich Chancellor. It was all chance, just as there was no inevitability in 1933. The other realisation: it can be fun to be a fascist.

The cryptofascist myth will never cease to amaze me. Absolutely everybody in 1933 knew who “the fascists” were. The ones in Italy literally called themselves fascists, which was one way to identify them. The ones in Germany openly derided liberalism and dreamed of a nationalist revolution that would put an end to the hated bourgeois democracy of the Weimar Republic. Hitler was a national politician who wrote and spoke openly of his aims. Secret Hitler in no way “reflects the truth in the history books”. It is a deformed fantasy about modern politics, which reflects nothing so much as the burning demand for and the vanishing supply of actual Nazis to hyperventilate about.

Now it is true that a lot of erstwhile liberals went over to National Socialism after the Nazis seized power, but these were not the secret fascists of Grappian fever dreams. The were just followers, as are a great many of the self-professed liberals active today. Were communists or illiberal nationalists to take over tomorrow, millions of people would line up behind the new political ideology like the sheep that they are, and I suspect that Grapp would be right at the head of that line.

Because our crack fascist identifiers suffer from a crushing lack of self-awareness, they declare that “relapsing into fascism is the primal fear of modern democratic societies”. Such a relapse, they explain, “long sounded hysterical and unimaginable”, but “now it seems serious and real”.

August 12, 2024

QotD: The key attraction of video games to young men

That would explain video game escapism/addiction amongst men. It’s a little world where there are predictable rules and outcomes and one can succeed much easier than in the unpredictable real world with ever-changing rules.

I think this is a really important point deserving of more attention.

Yes. Video games are a drug aimed straight at the receptor that is male need for agency. They’re a superstimulus for it in exactly the same way that pornography is a superstimulus for desire.

I don’t have a policy prescription about this or anything. But it’s a connection that matters.

ESR, Twitter, 2024-05-06.

August 4, 2024

June 13, 2024

April 12, 2024

QotD: Prepper fantasy versus prepper reality

… note that this is also a bit of a rebuke to the dominant strain of prepper fantasies, such as those I began this review with. Prepper fantasies are most fundamentally fantasies of agency, dreams that in the right crisis the actions you take could actually matter, and that in the wake of that crisis you could return to a Rousseauian condition of autonomous activity freed from the internal conflicts engendered by societal oppression (whether that oppression takes the form of stifling social convention or HRified bureaucratic fiat). It’s obvious how the prepper fantasies relate to the great survival stories like Robinson Crusoe, or to the pioneer dramas of the American Westward expansion. It’s a little less obvious, but just as deeply true, that they’re connected to stories of rogues, rascals, and reavers like those by Robert E. Howard or Bronze Age Pervert. All of these stories, fundamentally, are about how a man freed from external restraint and internal conflict can apply himself to better his condition.

The thing is these stories are totally ahistorical — the best that solitary survivors have ever managed was to survive, none of them have rebuilt civilization. As Jane notes in her review of BAP, the sandal-clad barbarians have generally been subjected to a “tyranny of the cousins” even more intrusive and meticulous than the gynocratic safetyism that Bronze Age Lifestyle offers an imaginative escape from. And as for the pioneers, Tanner Greer notes that:

Many imagine the great American man of the past as a prototypical rugged individual, neither tamed nor tameable, bestriding the wilderness and dealing out justice in lonesome silence. But this is a false myth. It bears little resemblance to the actual behavior of the American pioneer, nor to the kinds of behaviors and norms that an agentic culture would need to cultivate today. Instead, the primary ideal enshrined and ritualized as the mark of manhood was “publick usefuleness”, similar, if not quite identical, to the classical concept of virtus. American civilization was built not by rugged individuals but by rugged communities. Manhood was understood as the leadership of and service to these communities.

It would be too easy to end the review here, with the implication that the prepper identity is a fantasy of radical individualism and like all such fantasies, kinda dumb. But the thing is, the prepper world has by and large absorbed this critique and incorporated it into its theorizing. In contrast to the libertarian fantasies of the 1970s, second-wave prepperism (reformed prepperism?) is constantly talking about community, the importance of having friends you can trust, of cultivating deep social bonds with your neighbors, etc.

What Yu Gun reminds us is that this is still totally ahistorical, but this time in a way that indicts not only the preppers, but also a much broader swathe of our society. A man without a community is unnatural, but so is a community without leadership, hierarchy, and order. The prepper version of community is a vision of freely contracting individuals respecting each others’ autonomy while cooperating because it’s in their best interests. This is also the folk version of community that motivates much of our economic and legal regime. Scratch an American “communitarian”, and underneath it’s just another individualist.

If you hang out on prepper forums, a recurrent mantra is to “practice your preps”, that is to start living on the margin as if the apocalypse had already occurred. The purpose of this is to gain experience in the skills you’ll need after the end, and to work out the kinks in your routine now, while it’s still easy to make adjustments. Originally this meant practicing getting lost in the woods, using and maintaining your weapon of choice, eating some of your food stockpile, or whatever. In second-wave prepperism it means all that, plus a bunch of new stuff like hanging out with your neighbors, attending community barbecues, and whatever else it is that freely contracting individuals like to autonomously do while temporarily occupying the same space.

But for we third-wave preppers, it has to take on a very different meaning. Greer’s essay that I quoted above is mainly about how leadership and service in local-scale organizations served as training for leadership and service in much larger groups aimed at problems with much higher stakes. In other words, they were practicing their preps. One of the great secrets of leadership is that following and leading are actually closely related skills, and that practice at one of them transfers well to the other. This is difficult for we Americans to see, because an aversion to hierarchy is built into our national character, and consequently we operate with impoverished models of what it means to be in a position of authority or of subordination.

Long ago I read an article contrasting Western and Korean massively-multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Even if you know nothing about computer games, you probably know that in most of them you are the hero, the chosen one, the child of destiny. Talk about fantasies of agency! MMORPGs thus have a tricky needle to thread — somehow all the thousands and thousands of players need to simultaneously be the chosen one, the child of destiny, etc., etc. And they mostly accomplish this by just rolling with it and asking everybody to suspend disbelief. But this article claimed that Korean MMORPGs are different — when players join these games, they’re randomly assigned a role. A tiny fraction might become kings or generals or children of destiny, with the power to decide the fates of peoples and kingdoms, but most are given a role as ordinary soldiers or porters or blacksmiths, and toil away at their in-game mundane tasks, without much ability to affect anything at all.

We like to imagine that after the bombs fall and the smoke clears we will emerge as the new Yu Gun, apportioning merit and assigning tasks. And perhaps you will indeed be called upon to do that, so you should prepare yourself to step up and do it. That preparation will involve some practice commanding others and some practice obeying others’ commands, because the two are inextricably bound together. But in life as in Korean video games, there’s isn’t very much room at the top. Far more likely, when the stage of history is set, we will be cast in a supporting role, like the Korean gamer assigned to role-play as a peasant or like Yu’s followers standing in orderly ranks. Let us not turn our noses up at this vocation, the poorly-behaved seldom make history.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900 by David A. Graff”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-06-05.

February 13, 2024

QotD: War elephant logistics

From trunk to tail, elephants are a logistics nightmare.

And that begins almost literally at birth. For areas where elephants are native, nature (combined, typically, with the local human terrain) create a local “supply”. In India this meant the elephant forests of North/North-Eastern India; the range of the North African elephant (Loxodonta africana pharaohensis, the most likely source of Ptolemaic and Carthaginian war elephants) is not known. Thus for many elephant-wielding powers, trade was going to always be a key source for the animals – either trade with far away kingdoms (the Seleucids traded with the Mauyran Indian kingdom for their superior Asian elephants) or with thinly ruled peripheral peoples who lived in the forests the elephants were native to.

(We’re about to get into some of the specifics of elephant biology. If you are curious on this topic, I am relying heavily on R. Sukumar, The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management (1989). I’ve found that information on Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) much easier to come by than information on African elephants (Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis).)

In that light, creating a breeding program – as was done with horses – seems like a great idea. Except there is one major problem: a horse requires about four years to reach maturity, a mare gestates a foal in eleven months and can go into heat almost immediately thereafter. By contrast, elephants reach adulthood after seventeen years, take 18-22 months to gestate and female elephants do not typically mate until their calf is weaned, four to five years after its birth. A ruler looking to build a stable of cavalry horses thus may start small and grow rapidly; a ruler looking to build a corps of war elephants is looking at a very slow process. This is compounded by the fact that elephants are notoriously difficult to breed in captivity. There is some speculation that the Seleucids nonetheless attempted this at Apamea, where they based their elephants – in any event, they seem to have remained dependent on imported Indian elephants to maintain the elephant corps. If a self-sustaining elephant breeding program for war elephants was ever created, we do not know about it.

To make matters worse, elephants require massive amounts of food and water. In video-games, this is often represented through a high elephant “upkeep” cost – but this often falls well short of the reality of keeping these animals for war. Let’s take Total War: Rome II as an example: a unit of Roman (auxiliary) African elephants (12 animals), costs 180 upkeep, compared to 90 to 110 upkeep for 80 horses of auxiliary cavalry (there are quite a few types) – so one elephant (with a mahout) costs 15 upkeep against around 1.25 for a horse and rider (a 12:1 ratio). Paradox’s Imperator does something similar, with a single unit of war elephants requiring 1.08 upkeep, compared to just 0.32 for light cavalry; along with this, elephants have a heavy “supply weight” – twice that of an equivalent number of cavalry (so something like a 2:1 or 3:1 ratio of cost).

Believe it or not, this understates just how hungry – and expensive – elephants are. The standard barley ration for a Roman horse was 7kg of barley per day (7 Attic medimnoi per month; Plb. 6.39.12); this would be supplemented by grazing. Estimates for the food requirements of elephants vary widely (in part, it is hard to measure the dietary needs of grazing animals), but elephants require in excess of 1.5% of their body-weight in food per day. Estimates for the dietary requirements of the Asian elephant can range from 135 to 300kg per day in a mix of grazing and fodder – and remember, the preference in war elephants is for large, mature adult males, meaning that most war elephants will be towards the top of this range. Accounting for some grazing (probably significantly less than half of dietary needs) a large adult male elephant is thus likely to need something like 15 to 30 times the food to sustain itself as a stable-fed horse.

In peacetime, these elephants have to be fed and maintained, but on campaign the difficulty of supplying these elephants on the march is layered on top of that. We’ve discussed elsewhere the difficulty in supplying an army with food, but large groups of elephants magnify this problem immensely. The 54 elephants the Seleucids brought to Magnesia might have consumed as much food as 1,000 cavalrymen (that’s a rider, a horse and a servant to tend that horse and its rider).

But that still understates the cost intensity of elephants. Bringing a horse to battle in the ancient world required the horse, a rider and typically a servant (this is neatly implied by the more generous rations to cavalrymen, who would be expected to have a servant to be the horse’s groom, unlike the poorer infantry, see Plb. above). But getting a war elephant to battle was a team effort. Trautmann (2015) notes that elephant stables required riders, drivers, guards, trainers, cooks, feeders, guards, attendants, doctors and specialist foot-chainers (along with specialist hunters to capture the elephants in the first place!). Many of these men were highly trained specialists and thus had to be quite well paid.

Now – and this is important – pre-modern states are not building their militaries from the ground up. What they have is a package of legacy systems. In Rome’s case, the defeat of Carthage in the Second Punic War resulted in Rome having North African allies who already had elephants. Rome could accept those elephant allied troops, or say “no” and probably get nothing to replace them. In that case – if the choice is between “elephants or nothing” – then you take the elephants. What is telling is that – as Rome was able to exert more control over how these regions were exploited – the elephants vanished, presumably as the Romans dismantled or neglected the systems for capturing and training them (which they now controlled directly).

That resolves part of our puzzle: why did the Romans use elephants in the second and early first centuries B.C.? Because they had allies whose own military systems involved elephants. But that leaves the second part of the puzzle – Rome doesn’t simply fail to build an elephant program. Rome absorbs an elephant program and then lets it die. Why?

For states with scarce resources – and all states have scarce resources – using elephants meant not directing those resources (food, money, personnel, time and administrative capacity) for something else. If the elephant had no other value (we’ll look at one other use next week), then developing elephants becomes a simple, if difficult, calculation: are the elephants more likely to win the battle for me than the equivalent resources spent on something else, like cavalry. As we’ve seen above, that boils down to comparisons between having just dozens of elephants or potentially hundreds or thousands of cavalry.

The Romans obviously made the bet that investing in cavalry or infantry was a better use of time, money and resources than investing in elephants, because they thought elephants were unlikely to win battles. Given Rome’s subsequent spectacular battlefield success, it is hard to avoid the conclusion they were right, at least in the Mediterranean context.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part II: Elephants against Wolves”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-02.

September 27, 2023

QotD: Geeks and hackers

One of the interesting things about being a participant-observer anthropologist, as I am, is that you often develop implicit knowledge that doesn’t become explicit until someone challenges you on it. The seed of this post was on a recent comment thread where I was challenged to specify the difference between a geek and a hacker. And I found that I knew the answer. Geeks are consumers of culture; hackers are producers.

Thus, one doesn’t expect a “gaming geek” or a “computer geek” or a “physics geek” to actually produce games or software or original physics – but a “computer hacker” is expected to produce software, or (less commonly) hardware customizations or homebrewing. I cannot attest to the use of the terms “gaming hacker” or “physics hacker”, but I am as certain as of what I had for breakfast that computer hackers would expect a person so labeled to originate games or physics rather than merely being a connoisseur of such things.

One thing that makes this distinction interesting is that it’s a recently-evolved one. When I first edited the Jargon File in 1990, “geek” was just beginning a long march towards respectability. It’s from a Germanic root meaning “fool” or “idiot” and for a long time was associated with the sort of carnival freak-show performer who bit the heads off chickens. Over the next ten years it became steadily more widely and positively self-applied by people with “non-mainstream” interests, especially those centered around computers or gaming or science fiction. From the self-application of “geek” by those people it spread to elsewhere in science and engineering, and now even more widely; my wife the attorney and costume historian now uses the terms “law geek” and “costume geek” and is understood by her peers, but it would have been quite unlikely and a faux pas for her to have done that before the last few years.

Because I remembered the pre-1990 history, I resisted calling myself a “geek” for a long time, but I stopped around 2005-2006 – after most other techies, but before it became a term my wife’s non-techie peers used politely. The sting has been drawn from the word. And it’s useful when I want to emphasize what I have in common with have in common with other geeks, rather than pointing at the more restricted category of “hacker”. All hackers are, almost by definition, geeks – but the reverse is not true.

The word “hacker”, of course, has long been something of a cultural football. Part of the rise of “geek” in the 1990s was probably due to hackers deciding they couldn’t fight journalistic corruption of the term to refer to computer criminals – crackers. But the tremendous growth and increase in prestige of the hacker culture since 1997, consequent on the success of the open-source movement, has given the hackers a stronger position from which to assert and reclaim that label from abuse than they had before. I track this from the reactions I get when I explain it to journalists – rather more positive, and much more willing to accept a hacker-lexicographer’s authority to pronounce on the matter, than in the early to mid-1990s when I was first doing that gig.

Eric S. Raymond, “Geeks, hackers, nerds, and crackers: on language boundaries”, Armed and Dangerous, 2011-01-09.