Now I should note that the initial response in Italy to the shocking appearance of effective siege artillery was not to immediately devise an almost entirely new system of fortifications from first principles, but rather – as you might imagine – to hastily retrofit old fortresses. But […] we’re going to focus on the eventual new system of fortresses which emerge, with the first mature examples appearing around the first decades of the 1500s in Italy. This system of European gunpowder fort that spreads throughout much of Europe and into the by-this-point expanding European imperial holdings abroad (albeit more unevenly there) goes by a few names: “bastion” fort (functional, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment), “star fort” (marvelously descriptive), and the trace italienne or “the Italian line”. since that was where it was from.

Since the goal remains preventing an enemy from entering a place, be that a city or a fortress, the first step has to be to develop a wall that can’t simply be demolished by artillery in a good afternoon or two. The solution that is come upon ends up looking a lot like those Chinese rammed earth walls: earthworks are very good at absorbing the impact of cannon balls (which, remember, are at this point just that: stone and metal balls; they do not explode yet): small air pockets absorb some of the energy of impact and dirt doesn’t shatter, it just displaces (and not very far: again, no high explosive shells, so nothing to blow up the earthwork). Facing an earthwork mound with stonework lets the earth absorb the impacts while giving your wall a good, climb-resistant face.

So you have your form: a stonework or brick-faced wall that is backed up by essentially a thick earthen berm like the Roman agger. Now you want to make sure incoming cannon balls aren’t striking it dead on: you want to literally play the angles. Inclining the wall slightly makes its construction easier and the end result more stable (because earthworks tend not to stand straight up) and gives you an non-perpendicular angle of impact from cannon when they’re firing at very short range (and thus at very low trajectory), which is when they are most dangerous since that’s when they’ll have the most energy in impact. Ideally, you’ll want more angles than this, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Because we now have a problem: escalade. Remember escalade?

Earthworks need to be wide at the base to support a meaningful amount of height, tall-and-thin isn’t an option. Which means that in building these cannon resistant walls, for a given amount of labor and resources and a given wall circuit, we’re going to end up with substantially lower walls. We can enhance their relative height with a ditch several out in front (and we will), but that doesn’t change the fact that our walls are lower and also that they now incline backwards slightly, which makes them easier to scale or get ladders on. But obviously we can’t achieved much if we’ve rendered our walls safe from bombardment only to have them taken by escalade. We need some way to stop people just climbing over the wall.

The solution here is firepower. Whereas a castle was designed under the assumption the enemy would reach the foot of the wall (and then have their escalade defeated), if our defenders can develop enough fire, both against approaching enemies and also against any enemy that reaches the wall, they can prohibit escalade. And good news: gunpowder has, by this point, delivered much more lethal anti-personnel weapons, in the form of lighter cannon but also in the form of muskets and arquebuses. At close range, those weapons were powerful enough to defeat any shield or armor a man could carry, meaning that enemies at close range trying to approach the wall, set up ladders and scale would be extremely vulnerable: in practice, if you could get enough muskets and small cannon firing at them, they wouldn’t even be able to make the attempt.

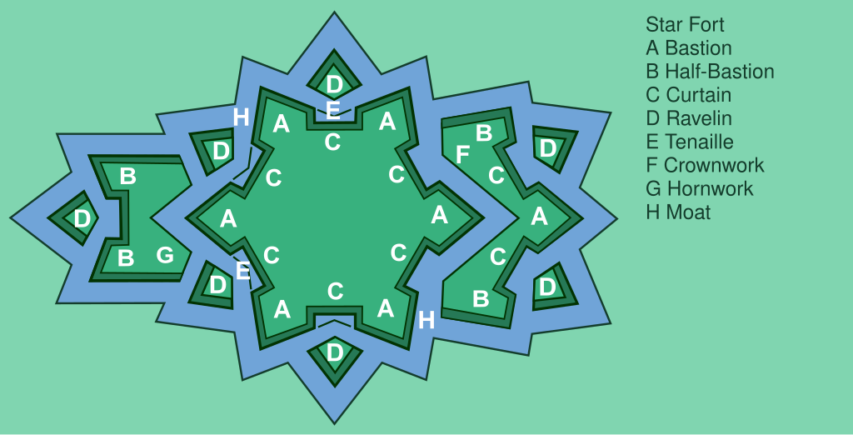

But the old projecting tower of the castle, you will recall, was designed to allow only a handful of defenders fire down any given section of wall; we still want that good enfilade fire effect, but we need a lot more space to get enough muskets up there to develop that fire. The solution: the bastion. A bastion was an often diamond or triangular-shaped projection from the wall of the fort, which provided a longer stretch of protected wall which could fire down the length of the curtain wall. It consists of two “flanks” which meet the curtain wall and are perpendicular to it, allowing fire along the wall; the “faces” (also two) then face outward, away from the fort to direct fire at distant besiegers. When places at the corners of forts, this setup tends to produce outward-spiked diamonds, while a bastion set along a flat face of curtain wall tends to resemble an irregular pentagon (“home plate”) shape [Wiki]. The added benefit for these angles? From the enemy siege lines, they present an oblique profile to enemy artillery, making the bastions quite hard to batter down with cannon, since shots will tend to ricochet off of the slanted line.

In the simplest trace italienne forts [Wiki], this is all you will need: four or five thick-and-low curtain walls to make the shape, plus a bastion at each corner (also thick-and-low, sometimes hollow, sometimes all at the height of the wall-walk), with a dry moat (read: big ditch) running the perimeter to slow down attackers, increase the effective height of the wall and shield the base of the curtain wall from artillery fire.

But why stay simple, there’s so much more we can do! First of all, our enemy, we assume, have cannon. Probably lots of cannon. And while our walls are now cannon resistant, they’re not cannon immune; pound on them long enough and there will be a breach. Of course collapsing a bastion is both hard (because it is angled) and doesn’t produce a breach, but the curtain walls both have to run perpendicular to the enemy’s firing position (because they have to enclose something) and if breached will allow access to the fort. We have to protect them! Of course one option is to protect them with fire, which is why our bastions have faces; note above how while the flanks of the bastions are designed for small arms, the faces are built with cannon in mind: this is for counter-battery fire against a besieger, to silence his cannon and protect the curtain wall. But our besieger wouldn’t be here if they didn’t think they could decisively outshoot our defensive guns.

But we can protect the curtain further, and further complicate the attack with outworks [Wiki], effectively little mini-bastions projecting off of the main wall which both provide advanced firing positions (which do not provide access to the fort and so which can be safely abandoned if necessary) and physically obstruct the curtain wall itself from enemy fire. The most basic of these was a ravelin (also called a “demi-lune”), which was essentially a “flying” bastion – a triangular earthwork set out from the walls. Ravelins are almost always hollow (that is, the walls only face away from the fort), so that if attackers were to seize a ravelin, they’d have no cover from fire coming from the main bastions and the curtain wall.

And now, unlike the Modern Major-General, you know what is meant by a ravelin … but are you still, in matters vegetable, animal and mineral, the very model of a modern Major-General?

But we can take this even further (can you tell I just love these damn forts?). A big part of our defense is developing fire from our bastions with our own cannon to force back enemy artillery. But our bastions are potentially vulnerable themselves; our ravelins cover their flanks, but the bastion faces could be battered down. We need some way to prevent the enemy from aiming effective fire at the base of our bastion. The solution? A crownwork. Essentially a super-ravelin, the crownwork contains a full bastion at its center (but lower than our main bastion, so we can fire over it), along with two half-bastions (called, wait for it, “demi-bastions”) to provide a ton of enfilade fire along the curtain wall, physically shielding our bastion from fire and giving us a forward fighting position we can use to protect our big guns up in the bastion. A smaller version of the crownwork, called a hornwork can also be used: this is just the two half-bastions with the full bastion removed, often used to shield ravelins (so you have a hornwork shielding a ravelin shielding the curtain wall shielding the fort). For good measure, we can connect these outworks to the main fort with removable little wooden bridges so we can easily move from the main fort out to the outworks, but if the enemy takes an outwork, we can quickly cut it off and – because the outworks are all made hollow – shoot down the attackers who cannot take cover within the hollow shape.

An ideal form of a bastion fortress to show each kind of common work and outwork.

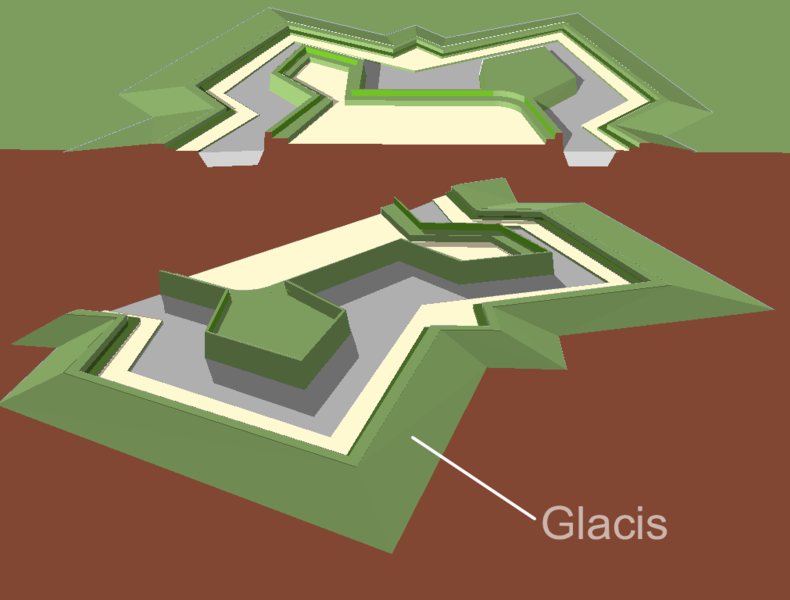

Drawing by Francis Lima via Wikimedia Commons.We can also do some work with the moat. By adding an earthwork directly in front of it, which arcs slightly uphill, called a glacis, we can both put the enemy at an angle where shots from our wall will run parallel to the ground, thus exposing the attackers further as they advance, and create a position for our own troops to come out of the fort and fire from further forward, by having them crouch in the moat behind the glacis. Indeed, having prepared, covered forward positions (which are designed to be entirely open to the fort) for firing from at defenders is extremely handy, so we could even put such firing positions – set up in these same, carefully mathematically calculated angle shapes, but much lower to the ground – out in front of the glacis; these get all sorts of names: a counterguard or couvreface if they’re a simple triangle-shape, a redan if they have something closer to a shallow bastion shape, and a flèche if they have a sharper, more pronounced face. Thus as an enemy advances, defending skirmishers can first fire from the redans and flèches, before falling back to fire from the glacis while the main garrison fires over their heads into the enemy from the bastions and outworks themselves.

A diagram showing a glacis supporting a pair of bastions, one hollow, one not.

Diagram by Arch via Wikimedia Commons.At the same time, a bastion fortress complex might connect multiple complete circuits. In some cases, an entire bastion fort might be placed within the first, merely elevated above it (the term for this is a “cavalier“) so that both could fire, one over the other. Alternately, when entire cities were enclosed in these fortification systems (and that was common along the fracture zones between the emerging European great powers), something as large as a city might require an extensive fortress system, with bastions and outworks running the whole perimeter of the city, sometimes with nearly complete bastion fortresses placed within the network as citadels.

Fort Saint-Nicolas, which dominates the Old Port of Marseille. The fort forms part of a system with the low outwork you see here and also an older refitted castle, Fort Saint-Jean, on the other side of the harbor.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.All of this geometry needed to be carefully laid out to ensure that all lines of approach were covered with as much fire as possible and that there were no blindspots along the wall. That in turn meant that the designers of these fortresses needed to be careful with their layout: the spacing, angles and lines all needed to be right, which required quite a lot of math and geometry to manage. Combined with the increasing importance of ballistics for calculating artillery trajectories, this led to an increasing emphasis on mathematics in the “science of warfare”, to the point that some military theorists began to argue (particularly as one pushes into the Enlightenment with its emphasis on the power of reason, logic and empirical investigation to answer all questions) that military affairs could be reduced to pure calculation, a “hard science” as it were, a point which Clausewitz (drink!) goes out of his way to dismiss (as does Ardant du Picq in Battle Studies, but at substantially greater length). But it isn’t hard to see how, in the heady centuries between 1500 and 1800 how the rapid way that science had revolutionized war and reduced activities once governed by tradition and habit to exercises in geometry, one might look forward and assume that trend would continue until the whole affair of war could be reduced to a set of theorems and postulates. It cannot be, of course – the problem is the human element (though the military training of those centuries worked hard to try to turn men into “mechanical soldiers” who could be expected to perform their role with the same neat mathmatical precision of a trace italienne ravelin). Nevertheless this tension – between the science of war and its art – was not new (it dates back at least as far as Hellenistic military manuals) nor is it yet settled.

An aerial view of the Bourtange Fortress in Groningen, Netherlands. Built in 1593, the fort has been restored to its 1750s configuration, seen here.

Photo by Dack9 via Wikimedia Commons.But coming back to our fancy forts, of course such fortresses required larger and larger garrisons to fire all of the muskets and cannon that their firepower oriented defense plans required. Fortunately for the fortress designers, state capacity in Europe was rising rapidly and so larger and larger armies were ready to hand. That causes all sorts of other knock on effects we’re not directly concerned with here (but see the bibliography at the top). For us, the more immediate problem is, well, now we’ve built one of these things … how on earth does one besiege it?

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part IV: French Guns and Italian Lines”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-17.

November 28, 2024

QotD: The trace italienne in fortification design

November 8, 2024

Highlights of Herculaneum (Part II)

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published Jul 12, 2024This second part of my survey of Herculaneum explores some of the site’s incredibly well-preserved houses.

(more…)

November 7, 2024

Highlights of Herculaneum (Part I)

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published Jul 9, 2024An introduction to Herculaneum, buried and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. This video surveys the site and some of its public monuments. Part II explores Herculaneum’s incredibly well-preserved houses.

Check out my other channels, @toldinstone and @toldinstonefootnotes

November 5, 2024

History of Ostia Antica: The Best Preserved Ancient Roman City in the World

Augustinian Thomist

Published Jul 4, 2024A 4k documentary and historical tour of the most well preserved ancient Roman city in the world filmed on site.

– Contents –

00:00 Introduction of Roman Ostia

01:10 Necropolis outside city gate

01:50 City gate

02:26 Early history of Ostia

04:41 Baths of Neptune

06:55 Theater of Ostia

12:10 House of the Infant Hercules

12:50 Square of Corporation Temple and Mosaics

21:21 Altar of Romulus and Remus

23:15 Four temple sanctuary

23:57 Temple of Pertinax

27:28 Grand Warehouse of Ostia

28:26 House of the Millstones

28:56 Ostia’s synagogues: Europe’s oldest synagogues

30:30 Ancient apartment buildings: House of the Paintings and House of the infant Bacchus

31:50 House of Jupiter and Ganymede

32:43 Ancient wine bar

34:50 House of Diana

36:25 Square of the Lares

37:45 Main Forum of Ostia, Temple of Jupiter

41:36 Baths of the Coachmen

(more…)

October 27, 2024

Reading the Herculaneum Papyri

Toldinstone Footnotes

Published Jul 5, 2024On this episode of the Toldinstone Podcast, Dr. Federica Nicolardi and I discuss the challenges of reading scrolls charred and buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Chapters:

00:00 Discovery of the scrolls

03:23 Opened and unopened

05:17 How to handle charred papyrus

09:11 New texts

13:17 Philodemus of Gadara

16:04 Epicurean philosophy

20:20 The library in the Villa of the Papyri

24:05 The Vesuvius Challenge

25:56 Progress so far …

28:44 The newest text

30:06 What comes next

34:20 What’s still buried?

October 26, 2024

Secrets of the Herculaneum Papyri

toldinstone

Published Jul 5, 2024The Herculaneum papyri, scrolls buried and charred by Vesuvius, are the most tantalizing puzzle in Roman archaeology. I recently visited the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples, where most of the papyri are kept, and discussed the latest efforts to decipher the scrolls with Dr. Federica Nicolardi.

My interview with Dr. Nicolardi: https://youtu.be/gs1Z-YN1aQMChapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:40 Opening the scrolls

1:47 A visit to the library

2:38 A papyrologist at work

4:00 The Vesuvius Challenge

4:46 What the scrolls say

5:40 Contents of the unopened scrolls

6:28 The other library

7:12 An interview with Dr. Nicolardi

(more…)

October 20, 2024

The True History of Deep Dish Pizza

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jul 2, 2024Deep dish cheese pizza with a bready crust

City/Region: Chicago

Time Period: 1945 | 1947The unsung hero of deep dish pizza is a woman named Alice Mae Redmond, who was the head chef at famous pizzerias like Pizzeria Uno and Gino’s. It seems like wherever she went, that was the best pizza place in town. She’s also the one who changed deep dish pizza crust from the bready version in this recipe to a butterier, more biscuit-like version that is found in modern deep dish.

This crust is still delicious, and the sauce is super flavorful. Be sure to cook the sauce down enough so that it’s nice and thick (mine was a bit too watery for my taste). In the 1940s, you could get cheese OR anchovies OR sausage, but not any of them together. I made a cheese pizza with my preferred ratio of about 50/50 cheese to sauce, but feel free to change things up however you like. You could even add more than one topping, though it won’t be quite as historically accurate.

(more…)

October 11, 2024

QotD: Fascists are inherently bad at war

For this week’s musing, I wanted to take the opportunity to expand a bit on a topic that I raised on Twitter which draw a fair bit of commentary: that fascists and fascist governments, despite their positioning are generally bad at war. And let me note at the outset, I am using fascist fairly narrowly – I generally follow Umberto Eco’s definition (from “Ur Fascism” (1995)). Consequently, not all authoritarian or even right-authoritarian governments are fascist (but many are). Fascist has to mean something more specific than “people I disagree with” to be a useful term (mostly, of course, useful as a warning).

First, I want to explain why I think this is a point worth making. For the most part, when we critique fascism (and other authoritarian ideologies), we focus on the inability of these ideologies to deliver on the things we – the (I hope) non-fascists – value, like liberty, prosperity, stability and peace. The problem is that the folks who might be beguiled by authoritarian ideologies are at risk precisely because they do not value those things – or at least, do not realize how much they value those things and won’t until they are gone. That is, of course, its own moral failing, but society as a whole benefits from having fewer fascists, so the exercise of deflating the appeal of fascism retains value for our sake, rather than for the sake of the would-be fascists (though they benefit as well, as it is, in fact, bad for you to be a fascist).

But war, war is something fascists value intensely because the beating heart of fascist ideology is a desire to prove heroic masculinity in the crucible of violent conflict (arising out of deep insecurity, generally). Or as Eco puts it, “For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life, but, rather, life is lived for struggle … life is permanent warfare” and as a result, “everyone is educated to become a hero“. Being good at war is fundamentally central to fascism in nearly all of its forms – indeed, I’d argue nothing is so central. Consequently, there is real value in showing that fascism is, in fact, bad at war, which it is.

Now how do we assess if a state is “good” at war? The great temptation here is to look at inputs: who has the best equipment, the “best” soldiers (good luck assessing that), the most “strategic geniuses” and so on. But war is not a baseball game. No one cares about your RBI or On-Base percentage. If a country’s soldiers fight marvelously in a way that guarantees the destruction of their state and the total annihilation of their people, no one will sing their praises – indeed, no one will be left alive to do so.

Instead, war is an activity judged purely on outcomes, by which we mean strategic outcomes. Being “good at war” means securing desired strategic outcomes or at least avoiding undesirable ones. There is, after all, something to be said for a country which manages to salvage a draw from a disadvantageous war (especially one it did not start) rather than total defeat, just as much as a country that conquers. Meanwhile, failure in wars of choice – that is, wars a state starts which it could have equally chosen not to start – are more damning than failures in wars of necessity. And the most fundamental strategic objective of every state or polity is to survive, so the failure to ensure that basic outcome is a severe failure indeed.

Judged by that metric, fascist governments are terrible at war. There haven’t been all that many fascist governments, historically speaking and a shocking percentage of them started wars of choice which resulted in the absolute destruction of their regime and state, the worst possible strategic outcome. Most long-standing states have been to war many times, winning sometimes and losing sometimes, but generally able to preserve the existence of their state even in defeat. At this basic task, however, fascist states usually fail.

The rejoinder to this is to argue that, “well, yes, but they were outnumbered, they were outproduced, they were ganged up on” – in the most absurd example, folks quite literally argued that the Nazis at least had a positive k:d (kill-to-death ratio) like this was a game of Call of Duty. But war is not a game – no one cares what your KDA is if you lose and your state is extinguished. All that matters is strategic outcomes: war is fought for no other purpose because war is an extension of policy (drink!). Creating situations – and fascist governments regularly created such situations. Starting a war in which you will be outnumbered, ganged up on, outproduced and then smashed flat: that is being bad at war.

Countries, governments and ideologies which are good at war do not voluntarily start unwinnable wars.

So how do fascist governments do at war? Terribly. The two most clear-cut examples of fascist governments, the ones most everyone agrees on, are of course Mussolini’s fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Fascist Italy started a number of colonial wars, most notably the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which it won, but at ruinous cost, leading it to fall into a decidedly junior position behind Germany. Mussolini then opted by choice to join WWII, leading to the destruction of his regime, his state, its monarchy and the loss of his life; he managed to destroy Italy in just 22 years. This is, by the standards of regimes, abjectly terrible.

Nazi Germany’s record manages to somehow be worse. Hitler comes to power in 1933, precipitates WWII (in Europe) in 1939 and leads his country to annihilation by 1945, just 12 years. In short, Nazi Germany fought one war, which it lost as thoroughly and completely as it is possible to lose; in a sense the Nazis are necessarily tied for the position of “worst regime at war in history” by virtue of having never won a war, nor survived a war, nor avoided a war. Hitler’s decision, while fighting a great power with nearly as large a resource base as his own (Britain) to voluntarily declare war on not one (USSR) but two (USA) much larger and in the event stronger powers is an act of staggeringly bad strategic mismanagement. The Nazis also mismanaged their war economy, designed finicky, bespoke equipment ill-suited for the war they were waging and ran down their armies so hard that they effectively demodernized them inside of Russia. It is absolutely the case that the liberal democracies were unprepared for 1940, but it is also the case that Hitler inflicted upon his own people – not including his many, horrible domestic crimes – far more damage than he meted out even to conquered France.

Beyond these two, the next most “clearly fascist” government is generally Francisco Franco’s Spain – a clearly right-authoritarian regime, but there is some argument as to if we should understand them as fascist. Francoist Spain may have one of the best war records of any fascist state, on account of generally avoiding foreign wars: the Falangists win the Spanish Civil War, win a military victory in a small war against Morocco in 1957-8 (started by Moroccan insurgents) which nevertheless sees Spanish territory shrink (so a military victory but a strategic defeat), rather than expand, and then steadily relinquish most of their remaining imperial holdings. It turns out that the best “good at war” fascist state is the one that avoids starting wars and so limits the wars it can possibly lose.

Broader definitions of fascism than this will scoop up other right-authoritarian governments (and start no end of arguments) but the candidates for fascist or near-fascist regimes that have been militarily successful are few. Salazar (Portugal) avoided aggressive wars but his government lost its wars to retain a hold on Portugal’s overseas empire. Imperial Japan’s ideology has its own features and so may not be classified as fascist, but hardly helps the war record if included. Perón (Argentina) is sometimes described as near-fascist, but also avoided foreign wars. I’ve seen the Baathist regimes (Assad’s Syria and Hussein’s Iraq) described as effectively fascist with cosmetic socialist trappings and the military record there is awful: Saddam Hussein’s Iraq started a war of choice with Iran where it barely managed to salvage a brutal draw, before getting blown out twice by the United States (the first time as a result of a war of choice, invading Kuwait!), with the second instance causing the end of the regime. Syria, of course, lost a war of choice against Israel in 1967, then was crushed by Israel again in another war of choice in 1973, then found itself unable to control even its own country during the Syrian Civil War (2011-present), with significant parts of Syria still outside of regime control as of early 2024.

And of course there are those who would argue that Putin’s Russia today is effectively fascist (“Rashist”) and one can hardly be impressed by the Russian army managing – barely, at times – to hold its own in another war of choice against a country a fourth its size in population, with a tenth of the economy which was itself not well prepared for a war that Russia had spent a decade rearming and planning for. Russia may yet salvage some sort of ugly draw out of this war – more a result of western, especially American, political dysfunction than Russian military effectiveness – but the original strategic objectives of effectively conquering Ukraine seem profoundly out of reach while the damage to Russia’s military and broader strategic interests is considerable.

I imagine I am missing other near-fascist regimes, but as far as I can tell, the closest a fascist regime gets to being effective at achieving desired strategic outcomes in non-civil wars is the time Italy defeated Ethiopia but at such great cost that in the short-term they could no longer stop Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria and in the long-term effectively became a vassal state of Hitler’s Germany. Instead, the more standard pattern is that fascist or near-fascist regimes regularly start wars of choice which they then lose catastrophically. That is about as bad at war as one can be.

We miss this fact precisely because fascism prioritizes so heavily all of the signifiers of military strength, the pageantry rather than the reality and that pageantry beguiles people. Because being good at war is so central to fascist ideology, fascist governments lie about, set up grand parades of their armies, create propaganda videos about how amazing their armies are. Meanwhile other kinds of governments – liberal democracies, but also traditional monarchies and oligarchies – are often less concerned with the appearance of military strength than the reality of it, and so are more willing to engage in potentially embarrassing self-study and soul-searching. Meanwhile, unencumbered by fascism’s nationalist or racist ideological blinders, they are also often better at making grounded strategic assessments of their power and ability to achieve objectives, while the fascists are so focused on projecting a sense of strength (to make up for their crippling insecurities).

The resulting poor military performance should not be a surprise. Fascist governments, as Eco notes, “are condemned to lose wars because they are constitutionally incapable of objectively evaluating the force of the enemy”. Fascism’s cult of machismo also tends to be a poor fit for modern, industrialized and mechanized war, while fascism’s disdain for the intellectual is a poor fit for sound strategic thinking. Put bluntly, fascism is a loser’s ideology, a smothering emotional safety blanket for deeply insecure and broken people (mostly men), which only makes their problems worse until it destroys them and everyone around them.

This is, however, not an invitation to complacency for liberal democracies which – contrary to fascism – have tended to be quite good at war (though that hardly means they always win). One thing the Second World War clearly demonstrated was that as militarily incompetent as they tend to be, fascist governments can defeat liberal democracies if the liberal democracies are unprepared and politically divided. The War in Ukraine may yet demonstrate the same thing, for Ukraine was unprepared in 2022 and Ukraine’s friends are sadly politically divided now. Instead, it should be a reminder that fascist and near-fascist regimes have a habit of launching stupid wars and so any free country with such a neighbor must be on doubly on guard.

But it should also be a reminder that, although fascists and near-fascists promise to restore manly, masculine military might, they have never, ever actually succeeded in doing that, instead racking up an embarrassing record of military disappointments (and terrible, horrible crimes, lest we forget). Fascism – and indeed, authoritarianisms of all kinds – are ideologies which fail to deliver the things a wise, sane people love – liberty, prosperity, stability and peace – but they also fail to deliver the things they promise.

These are loser ideologies. For losers. Like a drunk fumbling with a loaded pistol, they would be humiliatingly comical if they weren’t also dangerous. And they’re bad at war.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, February 23, 2024 (On the Military Failures of Fascism)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-02-23.

September 30, 2024

Sulla, civil war, and dictatorship

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jun 5, 2024The latest instalment of the Conquered and the Proud looks at the first few decades of the first century BC. We deal with the final days of Marius, the rise of Sulla, the escalating spiral of civil wars and massacres as Rome’s traditional political system starts breaking down.

Primary Sources – Plutarch, Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Crassus, Cicero and Caesar. Appian Civil Wars and Mithridatic Wars.

Secondary (a small selection) –

P. Brunt, Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic & The Fall of The Roman Republic

A. Keaveney, Sulla – the last Republican

R. Seager, Pompey the Great: A political Biography

August 17, 2024

Caesar Marches on Rome – Historia Civilis Reaction

Vlogging Through History

Published Apr 23, 2024See the original here –

• Caesar Marches on Rome (49 B.C.E.)

See “Caesar Crosses the Rubicon” here –

• Caesar Crosses the Rubicon – Historia…#history #reaction

August 13, 2024

The Original Secret History

Tom Ayling

Published Apr 28, 2024This is the story of Procopius’s Secret History Of Justinian – originally written around 550, but not published until 1623.

In this video we look at how Procopius wrote the text, how it survived, almost unknown, for 1,000 years, how it came to be published in the 1620s, and the extraordinary ramifications when it was.

00:00 Introduction

00:44 The Original Composition Of The Secret History

02:40 The Survival Of The Text In Greek Manuscripts

05:56 The Rediscovery And Publication Of The Secret History

08:23 Secret Histories Go ViralTo learn more about Secret Histories, sign up to receive my catalogue of rare books devoted to the subject – https://www.tomwayling.co.uk/register

I couldn’t have made this video without the help of two works in particular. The first is Brian Croke’s magisterial Procopius: From Manuscripts To Books: 1400-1850. The second is The Secret History In Literature, 1660-1820 which is edited by Rebecca Bullard and Rachel Carnell.

My name’s Tom and I’m an antiquarian bookseller – you can browse the books I have for sale on my website: https://www.tomwayling.co.uk/

July 23, 2024

Why Most “Ancient” Buildings are Fakes

toldinstone

Published Apr 12, 2024Almost every ancient monument has been at least partially reconstructed, for a wide range of reasons …

Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

1:06 The Forum and Colosseum

2:27 The Ara Pacis

3:24 Early restorations

4:37 Mondly

5:47 Roman forts and baths

6:42 Knossos

7:23 The Stoa of Attalus

8:59 The Acropolis

10:05 When to restore?

(more…)

June 23, 2024

The Original Chef Boyardee Spaghetti Dinner

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 13 Mar 2024Absolutely fantastic tomato and meat sauce served over spaghetti tossed with butter and parmesan

City/Region: Cleveland, Ohio

Time Period: 1930sChef Boyardee was not born in Cleveland (sorry, 30 Rock), but in Borganovo, just outside of Piacenza in Italy. And his name was not Hector Boyardee, but Ettore Boiardi (boy-AR-dee). He opened an Italian restaurant in Cleveland in 1924, where the food was so popular that he frequently sent patrons home with bottles of his spaghetti sauce.

We can’t know exactly what that original sauce was, but this is from a family recipe and is probably pretty close. And it’s phenomenal. It’s fairly simple, but so good. You get a lot of the fresh basil, and the creaminess from mixing the butter and parmesan directly with the pasta is delicious. I don’t often make dishes from the show again, but I can see myself making this any day of the week.

(more…)

June 18, 2024

QotD: The peoples incorporated or “allied” to Rome in the Republic’s Italian expansion

In one way, pre-Roman Italy was quite a lot like Greece: it consisted of a bunch of independent urban communities situated on the decent farming land (that is the lowlands), with a number of less-urban tribal polities stretching over the less-farming-friendly uplands. While pre-Roman urban communities weren’t exactly like the Greek polis, they were fairly similar. Greek colonization beginning in the eighth century added actual Greek poleis to the Italian mix and frankly they fit in just fine. On the flip side, there were the Samnites, a confederation of tribal communities with some smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands not all that dissimilar to the Greek Aetolians, a confederation of tribal communities and smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands.

In one very important way, pre-Roman Italy was very much not like Greece: whereas in Greece all of those communities shared a single language, religion and broad cultural context, Roman Italy was a much more culturally complex place. Consequently, as the Romans slowly absorbed pre-Roman Italy into the Roman Italy of the Republic, that meant managing the truly wild variety of different peoples in their alliance system. Let’s quickly go through them all, moving from North to South.

The Romans called the region south of the Alps but north of the Rubicon River Cisalpine Gaul and while we think of it as part of Italy, the Romans did not. That said, Gallic peoples had pushed into Italy before and a branch of the Senones occupied the lands between Ariminum and Ancona. Although Gallic peoples were always a factor in Italy, the Romans don’t seem to have incorporated their communities as socii; indeed the Romans were generally at their most ruthless when it came to interactions with Gallic peoples (despite the tendency to locate the “unassimilable” people on the Eastern edge of Rome’s empire, it was in fact the Gauls that the Romans most often considered in this way, though as we will see, wrongly so). That’s not to say that there was no cultural contact, of course; the Romans ended up adopting almost all of the Gallic military equipment set, for instance. In any event, it wouldn’t be until the late first century BCE that Cisalpine Gaul was merged into Italy proper, so we won’t deal too much with the Gauls just yet. I do want to note that, when we are thinking about the diversity of the place, even to speak of “the Gauls” is to be terribly reductive, as we are really thinking of at least half a dozen different Gallic peoples (Senones, Boii, Inubres, Lingones, etc) along with the Ligures and the Veneti, who may have been blends of Gallic and Italic peoples (though we are more poorly informed about both than we’d like).

Moving south then, we first meet the Etruscans, who we’ve already discussed, their communities – independent cities joined together in defensive confederations before being converted into allies of the Romans – clustered on north-western coast of Italy. They had a language entirely unrelated to Latin – or indeed, any other known language – and their own unique religion and culture. The Romans adopted some portions of that culture (in particular the religious practices) but the Etruscans remained distinct well into the first century. While a number of Etruscan communities backed the Samnites in the Third Samnite War (298-290 BC) culminating in the Battle of Sentinum (295) as a last-ditch effort to prevent Roman hegemony over the peninsula, the Etruscans subsequently remained quite loyal to Rome, holding with the Romans in both the Second Punic and Social Wars. It is important to keep in mind that while we tend to talk about “the Etruscans” (as the Romans sometimes do) they would have thought of themselves first through their civic identity, as Perusines, Clusians, Populinians and so on (much like their Greek contemporaries).

Moving further south, we have the peoples of the Apennines (the mountain range that cuts down the center of Italy). The people of the northern Apennines were the Umbri (that is, Umbrian speakers), though this linguistic classification hides further cultural and political differences. We’ve met the Sabines – one such group, but there were also the Volsci and Marsi (the latter particularly well known for being hard fighters as allies to Rome; Appian reports that the Marsi had a saying prior to the Social War, “No Triumph against the Marsi nor without the Marsi”). Further south along the Apennines were the Oscan speakers, most notably the Samnites (who resisted the Romans most strongly) but also the Lucanians and Paelignians (the latter also get a reputation for being hard fighters, particularly in Livy). The Umbrian and Oscan language families are related (though about as different from each other as Italian from Spanish; they and Latin are not generally mutually intelligible) and there does seem to have been some cultural commonality between these two large groups, but also a lot of differences. Their religion included a number of practices and gods unknown to the Romans, some later adopted (Oscan Flosa adapted as Latin Flora, goddess of flowers) and some not (e.g. the “Sacred Spring” rite, Strabo 5.4.12).

Also Oscan speakers, the Campanians settled in Campania (surprise!) at some early point (perhaps around 1000-900 BC) and by the fifth century were living in urban communities politically more similar to Latium and Etruria (or Greece, which will make sense in a moment) than their fellow Oscan speakers in the hills above, to the point that the Campanians turned to Rome to aid them against the also-Oscan-speaking Samnites. The leading city of the Campanians was Capua, but as Fronda (op. cit.) notes, they were meaningful divisions among them; Capua’s very prominence meant that many of the other Campanians were aligned against it, a division the Romans exploited.

The Oscans struggled for territory in Southern Italy with the Greeks – told you we’d get to them. The Greeks founded colonies along the southern part of Italy, expelling or merging with the local inhabitants beginning in the seventh century. These Greek colonies have distinctive material culture (though the Italic peoples around them often adopted elements of it they found useful), their own language (Greek), and their own religion. I want to stress here that Greek religion is not equivalent to Roman religion, to the point that the Romans are sticklers about which gods are worshipped with Roman rites and which are worshipped with the ritus graecus (“Greek rites”) which, while not a point-for-point reconstruction of Greek rituals, did involve different dress, different interpretations of omens, and so on.

All of these peoples (except the Gauls) ended up in Rome’s alliance system, fighting as socii in Rome’s wars. The point of all of this is that this wasn’t an alliance between, say, the Romans and the “Italians” with the latter being really quite a lot like the Romans except not being from Rome. Rather, Rome had constructed a hegemony (an “alliance” in name only, as I hope we’ve made clear) over (::deep breath::) Latins, Romans, Etruscans, Sabines, Volsci, Marsi, Lucanians, Paelignians, Samnites, Campanians, and Greeks, along with some people we didn’t mention (the Falisci, Picenes – North and South, Opici, Aequi, Hernici, Vestini, etc.). Many of these groups can be further broken down – the Samnites consisted of five different tribes in a confederation, for instance.

In short, Roman Italy under the Republic was preposterously multicultural (in the literal meaning of that word) … and it turns out that’s why they won.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

June 11, 2024

EUquake 2024

Although the European elites have managed to move as much as they can out of the reach of democratic institutions, they still have to allow the illusion that the few things ordinary people can vote for still kinda, sorta matter. Ordinary people seem to have noticed this:

“I cannot act as if nothing has happened”, said a weary, dejected Emmanuel Macron, in an unplanned address to his nation last night. The French president, bruised by an unprecedented showing for the right-wing populist National Rally (RN) on Sunday’s European Parliament elections, immediately dissolved the French parliament and announced snap legislative elections. The first round will take place in just three weeks’ time.

When Macron was elected president in 2017, he promised the French people that they will “no longer have a single reason to vote for the extremes”. Pro-EU centrists hailed his apparent defeat of nationalist, populist forces. Seven years later, RN is on course to achieve its best-ever result in an EU election. Marine Le Pen’s party is projected to win double the vote share of the president’s liberal, centrist Renaissance group. Clearly, the French feel that they have more reasons than ever to revolt against the mainstream.

The French are not alone in this. The hard-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), despite two of its leading MEP candidates being dogged by major scandals, came second behind the centre-right CDU. Crucially, it beat all three of the parties in Germany’s governing coalition. The Social Democrats (SPD), led by chancellor Olaf Scholz, suffered its worst result of any nationwide election since the 1940s. According to one pollster, around a million people who supported the left-leaning parties in the “traffic light” coalition have since defected to the AfD. Pressure is now mounting on Scholz to call his own snap election. In Italy, meanwhile, Giorgia Meloni and her Brothers of Italy topped the European polls, exceeding the vote share that swept her into power in 2022’s national elections. Populist, right-wing and hard-right parties, therefore, came in first or second place in all three of the major EU nations.

Even Belgium, at the epicentre of the EU empire, has been struck by the populist earthquake. Prime minister Alexander de Croo announced his resignation last night as his party was beaten to below 10 per cent in Sunday’s federal parliamentary elections and to around five per cent in the European elections – squeezed by Flemish separatist parties. Hard-right parties also came first in Austria and second in the Netherlands.

While Macron has been forced to react to the scale of his defeat, acknowledging euphemistically that these elections were “not a good result for the parties that defend Europe”, others in the Brussels oligarchy have tried to bury their heads in the sand. On Sunday evening, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen declared – delusionally – that “the centre is holding”.

She is right in one, very narrow, sense. The centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the liberal Renew group have likely gained enough seats between them for business as usual to resume in the European Parliament. The two groupings to their right – the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) – have not made enough gains, even when combined, to start throwing their weight around in Brussels. Von der Leyen’s own position as Commission president is likely secure, not least because her EPP is the single largest grouping in parliament. The new populist MEPs will likely be shut out of key decisions, including the vetting of new EU commissioners. The EU has never allowed the democratic wishes of the public to intrude on its affairs before, so it is unlikely to start now.

But Brussels cannot hide from reality forever. These elections clearly show that the EU and its boosters are failing to contain the public’s anger. European elites have pulled every trick in the book to try to put the brakes on the populist surge, seemingly to little avail.

How bad was the rejection of the kakistocrats in France? This bad: