Unfortunately, by any objective measure, most new things are bad. People are positively brimming with awful ideas. Ninety percent of startups and 70 percent of small businesses fail. Just 56 percent of patent applications are granted, and over 90 percent of those patents never make any money. Each year, 30,000 new consumer products are brought to market, and 95 percent of them fail. Those innovations that do succeed tend to be the result of an iterative process of trial-and-error involving scores of bad ideas that lead to a single good one, which finally triumphs. Even evolution itself follows this pattern: the vast majority of genetic mutations confer no advantage or are actively harmful. Skepticism towards new ideas turns out to be remarkably well-warranted.

The need for skepticism towards change is just as great when the innovation is social or political. For generations, many progressives embraced Marxism and thought its triumph inevitable. Future generations would view us as foolish for resisting it — just like Thoreau and the telegraph. But it turned out that Marxism was a terrible idea, and resisting it an excellent one. It had that in common with virtually every other utopian ideal in the history of social thought. Humans struggle to identify where precisely the arc of history is pointing.

Nicholas Phillips, “The Fallacy of Techno-Optimism”, Quillette, 2019-06-06.

September 7, 2023

QotD: Techno-pessimism

September 5, 2023

September 4, 2023

The temptations of envy

Rob Henderson discusses the phenomenon of envy in the modern world:

A couple of sample items in the social comparison scale are “I often compare myself with others with respect to what I have accomplished in life” and “I often compare how I am doing socially (social skills, popularity) with other people.”

Social comparison, by definition, is relative. Here is a question often used in these kinds of scales.

Suppose you are presented with two options:

A. You get 2 weeks of vacation; your coworkers get 1 week

B. You get 4 weeks of vacation; your coworkers get 8 weeks

A sensible, rational, objective person should choose B. One week of vacation versus 4 weeks is a no-brainer. But a surprisingly high number of people will choose A over B.

Consider the reality of working in an environment in which you know everyone gets twice as much vacation time as you. It’s unfair. And as we’ve discussed before, our preoccupation with the idea of fairness is in part rooted in concerns about status.

So what are some of the traits associated with social comparison orientation?

Unsurprisingly, social comparison orientation is associated with the Dark Triad personality traits (psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism), fear of failure, interest in exhibiting status, FoMo (Fear of Missing Out), utilitarian moral preferences, malicious envy, and benign envy. We’ll discuss the difference between these two forms of envy later.

The utilitarian finding is interesting. When you present trolley problems to people high on social comparison orientation, they are more likely to report that they would flip the switch to kill one person or push the fat man off the bridge in order to save five people. They seem to favor cold calculations for decision-making, which may be why they tend to score highly on psychopathy.

Narcissism is unsurprising. People who compare themselves with others are more likely to be preoccupied with their social image and want others to admire them and think highly of them.

This is of course related to fear of failure. Failure means that you come off looking comparatively worse than others. Social comparers are interested in status displays, that’s not a surprise given the link with narcissism.

In fact, some researchers have found that narcissistically-oriented people often report intense reactions to the perception of others’ envy. They experience a hidden sadistic satisfaction in causing a sense of inferiority and painful feelings in others.

Social comparers report greater levels of Fear of Missing Out, because if they are left out or excluded, this reflects poorly on them. Most people want to be a part of the excitement, but social comparers have an especially intense desire to be among those who are seen.

And this brings us to envy.

What is envy? Plainly, it is the emotional consequence of upward social comparison. Envy is an emotion that regulates the navigation of status hierarchies.

It is a painful emotion. People might say they will occasionally feel pride, or greed, or lust, but seldom do people confess to feelings of envy. To confess to envy is to acknowledge that you believe someone else has more status than you. Few people are eager to intentionally lower themselves in this way.

Envy is an unpleasant feeling, as many of your emotions are. But negative emotions are evolutionarily adaptive. Envy alerts you when you might be falling too low on the status ladder. It is a kind of status leveling mechanism.

Here’s how some psychologists have described it:

At its core, envy is born out of the perceived danger to lose respect and social influence in the eyes of others … envy’s function may be to foster the motivations to re-gain status or harm the superior position of others.

What does envy look like? Here’s a still from season 1 of the superb television series Mad Men.

Here, two advertising executives, Peter Campbell and Paul Kinsey, are reacting to their colleague Ken Cosgrove, who has just told them one of his stories was published in a prestigious magazine. Ken’s colleagues are smiling and congratulating him, but you can observe a bit of surprise, a bit of skepticism, and an attempt to show Ken that they are happy for him but also surprised that he had this talent for writing. It’s a way of being cordial while also communicating that Ken shouldn’t get too full of himself. This kind of contorted smile might be a uniquely American expression, because Americans are culturally conditioned to suppress envy and be happy for one another’s success. This is a good cultural practice, in my view.

There’s a term used in New Zealand and Australia called “Tall Poppy Syndrome”. The idea is that tall poppies, or people who rise too far up beyond others, get cut down because the smaller poppies are envious. Bids for status can incur envy in other people. If you try to achieve something, others might attack you or resent you or cut you down in some way. Some of you may be familiar with the crabs in the bucket metaphor, and this is similar to that idea of crabs at the bottom of the bucket pulling down the crabs higher in the bucket. People are often intuitively aware of this, which is why people conceal their desire for wealth or status or power.

September 2, 2023

August 29, 2023

The noble reasons New Jersey banned self-service gas stations

Of course, by “noble reasons” I mean “corrupt crony capitalist reasons“:

“Model A Ford in front of Gilmore’s historic Shell gas station” by Corvair Owner is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

New Jersey’s law, like Oregon’s, ostensibly stemmed from safety concerns. In 1949, the state passed the Retail Gasoline Dispensing Safety Act and Regulations, a law that was updated in 2016, which cited “fire hazards directly associated with dispensing fuel” as justification for its ban.

If the idea that Americans and filling stations would be bursting into flames without state officials protecting us from pumping gas sounds silly to you, it should. In fact, safety was not the actual reason for New Jersey’s ban (any more than Oregon’s ban was, though the state cited “increased risk of crime and the increased risk of personal injury resulting from slipping on slick surfaces” as justification).

To understand the actual reason states banned filling stations, look to the life of Irving Reingold (1921-2017), a maverick entrepreneur and workaholic who liked to fly his collection of vintage World War II planes in his spare time. Reingold created a gasoline crisis in the Garden State, in the words of New Jersey writer Paul Mulshine, “by doing something gas station owners hated: He lowered prices”.

In the late 1940s, gasoline was selling for about 22 cents a gallon in New Jersey. Reingold figured out a way to undercut the local gasoline station owners who had entered into a “gentlemen’s agreement” to maintain the current price. He’d allow customers to pump gas themselves.

“Reingold decided to offer the consumer a choice by opening up a 24-pump gas station on Route 17 in Hackensack,” writes Mulshine. “He offered gas at 18.9 cents a gallon. The only requirement was that drivers pump it themselves. They didn’t mind. They lined up for blocks.”

Consumers loved this bit of creative destruction introduced by Reingold. His competition was less thrilled. They decided to stop him — by shooting up his gas station. Reingold responded by installing bulletproof glass.

“So the retailers looked for a softer target — the Statehouse,” Mulshine writes. “The Gasoline Retailers Association prevailed upon its pals in the Legislature to push through a bill banning self-serve gas. The pretext was safety …”

The true purpose of New Jersey’s law had nothing to do with safety or “the common good”. It was old-fashioned cronyism, protectionism via the age-old bootleggers and Baptists grift.

Politicians helped the Gasoline Retailers Association drive Reingold out of business. He and consumers are the losers of the story, yet it remains a wonderful case study in public choice theory economics.

The economist James M. Buchanan received a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work that demonstrated a simple idea: Public officials tend to arrive at decisions based on self-interest and incentives, just like everyone else.

August 27, 2023

When the techno-utopians proclaimed the end of the book

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte harks back to a time when brash young tech evangelists were lining up to bury the ancient codex because everything would be online, accessible, indexed, and (presumably) free to access. That … didn’t happen the way they forsaw:

By the time I picked up Is This a Book?, a slim new volume from Angus Phillips and Miha Kova?, I’d forgotten the giddy digital evangelism of the mid-Aughts.

In 2006, for instance, a New York Times piece by Kevin Kelly, the self-styled “senior maverick” at Wired, proclaimed the end of the book.

It was already happening, Kelly wrote. Corporations and libraries around the world were scanning millions of books. Some operations were using robotics that could digitize 1,000 pages an hour, others assembly lines of poorly paid Chinese labourers. When they finished their work, all the books from all the libraries and archives in the world would be compressed onto a 50 petabyte hard disk which, said Kelly, would be as big as a house. But within a few years, it would fit in your iPod (the iPhone was still a year away; the iPad three years).

“When that happens,” wrote Kelly, “the library of all libraries will ride in your purse or wallet — if it doesn’t plug directly into your brain with thin white cords.”

But that wasn’t what really excited Kelly. “The chief revolution birthed by scanning books”, he ventured, would be the creation of a universal library in which all books would be merged into “one very, very, very large single text”, “the world’s only book”, “the universal library.”

The One Big Text.

In the One Big Text, every word from every book ever written would be “cross-linked, clustered, cited, extracted, indexed, analyzed, annotated, remixed, reassembled and woven deeper into the culture than ever before”.

“Once text is digital”, Kelly continued, “books seep out of their bindings and weave themselves together. The collective intelligence of a library allows us to see things we can’t see in a single, isolated book.”

Readers, liberated from their single isolated books, would sit in front of their virtual fireplaces following threads in the One Big Text, pulling out snippets to be remixed and reordered and stored, ultimately, on virtual bookshelves.

The universal book would be a great step forward, insisted Kelly, because it would bring to bear not only the books available in bookstores today but all the forgotten books of the past, no matter how esoteric. It would deepen our knowledge, our grasp of history, and cultivate a new sense of authority because the One Big Text would indisputably be the sum total of all we know as a species. “The white spaces of our collective ignorance are highlighted, while the golden peaks of our knowledge are drawn with completeness. This degree of authority is only rarely achieved in scholarship today, but it will become routine.”

And it was going to happen in a blink, wrote Kelly, if the copyright clowns would get out of the way and let the future unfold. He recognized that his vision would face opposition from authors and publishers and other friends of the book. He saw the clash as East Coast (literary) v. West Coast (tech), and mistook it for a dispute over business models. To his mind, authors and publishers were eager to protect their livelihoods, which depended on selling one copyright-protected physical book at a time, and too self-interested to realize that digital technology had rendered their business models obsolete. Silicon Valley, he said, had made copyright a dead letter. Knowledge would be free and plentiful—nothing was going to stop its indiscriminate distribution. Any efforts to do so would be “rejected by consumers and ignored by pirates”. Books, music, video — all of it would be free.

Kelly wasn’t altogether wrong. He’d just taken a narrow view of the book. He was seeing it as a container of information, an individual reference work packed with data, facts, and useful knowledge that needed to be agglomerated in his grander project. That has largely happened with books designed simply to convey information — manuals, guides, dissertations, and actual reference books. You can’t buy a good printed encyclopedia today and most scientific papers are now in databases rather than between covers.

What Kelly missed was that most people see the book as more than a container of information. They read for many reasons besides the accumulation of knowledge. They read for style and story. They read to feel, to connect, to stimulate their imaginations, to escape. They appreciate the isolated book as an immersive journey in the company of a compelling human voice.

August 26, 2023

“Email jobs”, as defined by Freddie deBoer

Freddie deBoer offers some notes on what he calls “a book I’ll probably never write”:

When I talk to people about college-educated workers, even informed people, there’s a constant tendency to immediately think of doctors, lawyers, engineers, data scientists … Reflexively, people seem to think of educated labor in terms of college graduates who a) tend to go on to some sort of graduate study, b) work in fields that directly utilize domain-specific knowledge from their majors or graduate education, and c) are generally high-income relative to the economy writ large. These professions, combined, are a healthy slice of our labor force, and there’s nothing wrong with paying an appropriate amount of attention to them. But I think the amount of attention they’re given in the educational and economic discourse is in fact disproportionate. And I also think that there’s a kind of profession that is intuitively very understandable but which (despite considerable effort on my part) remains very difficult to classify and thus to quantify. Though it has many names, I think my preferred term is “email job”.

[…]

To me, prototypical email jobs

- Depend, naturally, on email and other digital communicative tools like video conferencing, online calendars, and networked workspaces for the large majority of their actual productive capability

- Are staffed almost entirely by people with college degrees, but while they do take advantage of time management and organizational skills that can be developed in college, almost never call on domain-specific knowledge related to a particular major

- Dedicate a considerable amount of time not to the named productive goals of the job themselves but to meta-tasks that are meant to facilitate those goals (scheduling, coordinating, assigning responsibility, “touching base”, enhancing productivity, ensuring compliance with various HR-mediated job requirements and odd whims of the boss)

- Have no immediate observable impact on the material world; an email job might involve coordinating or supporting or assessing a project that will eventually move some atoms around, but the email job itself results only in the manipulation of bits

- Cannot be considered creative in any meaningful sense — they do not entail the production of new stories, scripts, code, images, video, blueprints, patents, research papers, etc — but may involve the creation of materials that are subsidiary to larger administrative goals, such as PowerPoint presentations, reports, postmortems, or white papers

- May or may not be partially or fully remote but could likely be performed fully remotely/on a “work from home” basis without issue

- Can involve supervising lower-level workers, even teams, but these positions are not themselves fundamentally supervisory and the holder of an email job is rarely the only “report” for anyone; these positions, in other words, are not executive or executive-track, though some may escape the email job track and gain entry to the executive track

- Tend to top out at middle management, and often have a salary range (with a great deal of wiggle) between $50,000 and $200,000/year.

Doctors do not have email jobs because the human bodies they treat exist in the world of atoms, not the world of bits, and their work involves domain-specific knowledge. There are some lawyers who are effectively in email jobs, as their law credentials are used for hiring purposes but their actual task is handling particular kinds of paperwork that a non-lawyer could complete, but most lawyers are not in email jobs as their work involves various functions at courthouses and otherwise away from the computer, and anyway their work too involves domain-specific knowledge. Most accountants and actuaries are not in email jobs as their jobs require domain-specific knowledge that they acquired in formal education. Architects create new things that will someday exist in the world of atoms and utilize domain-specific knowledge they learned in college. Programmers take advantage of skills gained in college to create new things that exist for their own purpose, rather than to satisfy other administrative functions. Professors don’t have email jobs, even those who work at online colleges, as working with students takes place in the world of atoms and they are constantly accessing domain-specific knowledge they learned in formal education. Screenwriters create something new; engineers move atoms and usually get graduate degrees; CEOs don’t have email jobs because they’re on the executive track and enjoy the ability to delegate most of the email work to subordinates. I could go on.

So who does have an email job? Take someone who works in accreditation at a college in a large public university system. He or she didn’t get a major in accreditation (there is no such major) and is unlikely to have majored in education, and even if they did they would have learned about pedagogy and “theory” and assessment rather than anything having to do with their daily work lives. Essentially everything they do for work takes place within the confines of their laptop screen, and the exception is various in-person meetings that accomplish nothing beyond delegating various tasks, defining roles, critiquing past performance, and otherwise reflecting on how to do a better job of supporting the tasks that other people do. A person in this job might have a secretary or lower-level administrative functionary that reports to them, but they are not on a track that makes advancement likely — becoming a VP somewhere will likely require many years of service and going on the job market to get a job at another school. A person in this position will never interact with students in any real capacity, demonstrating the psychic distance between email jobs and the actual function of their institutions. Though they have a clear and defined set of responsibilities written into their job description, their overall impact on the day-to-day functioning of their college is nebulous, and far more time is spent on administrivia than their “real” duties. They live between the 50th and 75th percentile for individual income in their state.

August 25, 2023

Shrinking traffic “is always a bad sign – but especially if your technology is touted as the biggest breakthrough of the century”

I don’t know about anyone else, but with every site I visit these days seeming to be eager that I try out their new AI, I’m deep in AI-fatigue. Ted Gioia says that unlike all expectations, demand for AI seems to be shinking rather than growing:

The AI hype is collapsing faster than the bouncy house after a kid’s birthday. Nothing has turned out the way it was supposed to.

For a start, take a look at Microsoft — which made the biggest bet on AI. They were convinced that AI would enable the company’s Bing search engine to surpass Google.

They spent $10 billion dollars to make this happen.

And now we have numbers to measure the results. Guess what? Bing’s market share hasn’t grown at all. Bing’s share of search It’s still stuck at a lousy 3%.

In fact, it has dropped slightly since the beginning of the year.

What’s wrong? Everybody was supposed to prefer AI over conventional search. And it turns out that nobody cares.

What makes this especially revealing is that Google search results are abysmal nowadays. They have filled them to the brim with garbage. If Google was ever vulnerable, it’s right now.

But AI hasn’t made a dent.

Of course, Google has tried to implement AI too. But the company’s Bard AI bot made embarrassing errors at its very first demo, and continues to do bizarre things—such as touting the benefits of genocide and slavery, or putting Hitler and Stalin on its list of greatest leaders.

So it’s no surprise that many people are now doing searches at Reddit or TikTok, instead of conventional search engines. This could have been Bing’s great opportunity, but instead its AI bot is turning into the next Clippy.

Consumers don’t want grotesque AI responses filled with errors and outrageous claims. Who could have guessed it?

The same decline is happening at ChatGPT’s website. Site traffic is now shrinking. This is always a bad sign — but especially if your technology is touted as the biggest breakthrough of the century.

If AI really delivered the goods, visitors to ChatGPT should be doubling every few weeks.

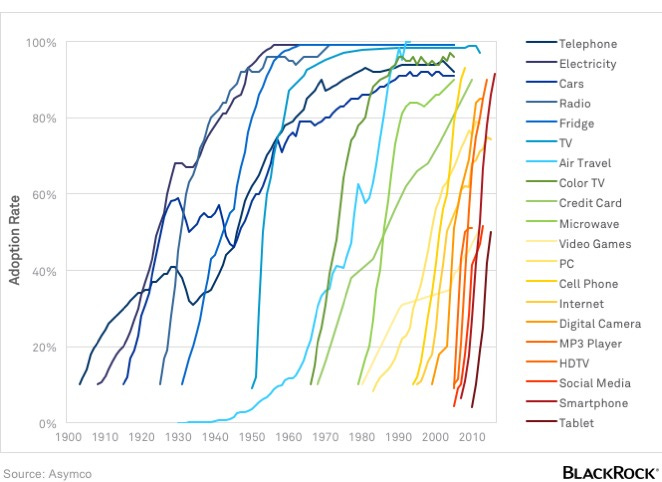

This is what a demand pattern for real innovation looks like.

How key innovations grew

(source)I used to study this stuff for a living — some people even called me the “King of the S-Curves” back then. (Hey, I’ve been called worse.)

As you can see, a real tech breakthrough grows at a ridiculously rapid pace in its early days. Look at how fast people adopted radio or the smartphone or electricity. And these required huge investments by consumers.

But they’re giving AI away for free at Bing — and it’s not growing at all.

This is not how consumers respond to transformative technology. The current demand pattern resembles, instead, what we would call a fad or craze.

And this is just one warning sign among many.

August 24, 2023

There Will Be  Pain

Pain (A Book Update)

(A Book Update)

Jill Bearup

Published 15 May 2023I’m just saying, One Crisis at a Time is our motto as well as our title. Have a Fantasy Heroine book update for your delectation and delight.

#fantasyheroine #onecrisisatatime

Pain

Pain (A Book Update)

(A Book Update) August 22, 2023

August 21, 2023

QotD: Effrontery, snake oil and TV preachers

… effrontery has made great strides as a key to success in life, and indeed quite ordinary people now employ it routinely. There are consultants in effrontery training who not only commit it themselves but teach others how to commit it, and charge large sums for doing so. There was a time when self-praise was regarded as no praise, rather the reverse; but now it is a prerequisite for advancement.

The other day I was sent a video of a young woman — elegant, attractive, and very self-confident — giving a seminar on how other young women, one of them the daughter of a friend, could and should change their lives for the better. In a way, I admired the leader of the seminar’s effrontery (just as I secretly admire Thomas Holloway’s). She spoke in pure, unadulterated clichés, practically contentless, but with such force of conviction that, if you discounted what she actually said, you might have thought that she was a person of profound insight with a vocation for imparting it to others. Her audience was as lambs to the slaughter, or at least to the fleece; they had paid a large sum of money to listen to mental pabulum that would make the recitation of a bus timetable seem intellectually stimulating.

On catching glimpses in the past of American television evangelists, it was always a cause of wonderment to me that anyone could look at or listen to them without immediately perceiving their fraudulence. This fraudulence was so obvious that it was like a physical characteristic, such as height or weight or color of hair, or alternatively like an emanation, such as body odor (incidentally, pictures of Guevara always suggest, to me at any rate, that he smelled). How could people fail to perceive it? Obviously, many did not, for the evangelists were very successful — financially, that is, the only criterion that counted for them.

But the attendees of the seminar of which I saw a video clip were well educated, and still they did not perceive the vacuity, and therefore the fraudulence, of the seminar that they attended at such great expense to themselves.

But was not my own surprise at their gullibility a manifestation of my own gullibility, in supposing that intelligence and education make a man wise, rather than more sophisticated in his foolishness?

But at least most of their victims were uneducated, relatively simple folk.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Way of Che”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-10-28.

August 20, 2023

How to decode book blurbs

In The Critic, “The Secret Author” provides a glossary for industry outsiders to understand what the apparently glowing words of a blurb on a book cover actually mean:

Like many other professions, the book trade is keen on jargon: lots of it, the more the merrier. As with those other professions, it tends to be of two kinds: outward-facing, when publishers communicate with their customers; and inward-facing, when they communicate with other publishers or the people who write the products they sell.

Its function — the function of all professional jargon, it might be said — is simultaneously to create an easily intelligible code for the benefit of insiders and (frankly) to mystify and impress those beyond the loop.

Publishers’ outward-facing jargon can be conveniently observed in the blurbs printed on book jackets. These are full of code words which, you may be surprised to learn, usually have very little to do with the contents.

A good place to start in any consideration of jacket copy might be the late Anthony Blond’s still invaluable The Publishing Game (1971), in which the one-time kingpin of Anthony Blond Ltd and various successor firms identifies the real meaning of several of the key publishers’ cliches of the late 1960s.

They include Kafkaesque (“obscure”), Saga (“the editor suggested cuts but the author was adamant”), Frank or outspoken (“obscene”) and Well-known, meaning “unknown”. To these may be added Rebellious (“the author uses bad language”), Savage (“the author revels in sadism”), Ingenious (“usually means unbelievable”) and Sensitive (“homosexual”). Blond also offers a list of OK writers (Kafka, J.D. Salinger) with whom promising newcomers may profitably be compared.

Naturally, Blond’s list is of its time: nobody these days would think of labelling a gay coming-of-age novel “sensitive”. On the other hand, if the content has been superannuated, here in 2023 very little has changed in the form — which is to say that the modern book blurb is still awash with genteel euphemism and downright obfuscation.

Sometimes a blurb-adjective means its exact opposite. Thus powerful can invariably be construed as “weak”, whilst audacious or bold generally means “deeply conventional”. Shocking, obviously, means “not shocking” and challenging “not at all challenging”.

Then there are the contemporary buzzwords: transgressive, used to describe anything even a degree or two north of the sexual or ideological status quo; or immersive, which is another way of saying “reasonably engrossing”.

August 18, 2023

When your friendly local bank turns into a branch of the Stasi

Theodore Dalrymple on the British bank — probably not the only one to do things like this — that compiled a “dossier” of information on one of their long-term clients with a view to de-banking him, his family, and associates. It might have worked if the client was a private citizen with no particular public profile, but the client was someone who absolutely is not that kind of man:

The following day, [National Westminster Bank CEO Alison] Rose resigned, admitting to “a serious error of judgment”. The value of the bank fell by more than $1 billion.

The weasel words of Ms. Rose and the bank board are worth examination. They deflected, and I suspect were intended to deflect, the main criticism directed at Ms. Rose and the bank: namely, that the bank had been involved in a scandalous and sinister surveillance of Mr. Farage’s political views and attempted to use them as a reason to deny him banking services, all in the name of their own political views, which they assumed to be beyond criticism or even discussion. The humble role of keeping his money, lending him money, or perhaps giving him financial advice, was not enough for them: they saw themselves as the guardians of correct political policy.

It was not that the words used to describe Mr. Farage were “inappropriate”, or even that they were libelous. It is that the bank saw fit to investigate and describe him at all, at least in the absence of any suspicion of fraud, money laundering, and so forth. “The error of judgment” to which Ms. Rose referred was not that she spoke to the BBC about his banking affairs (it is not easy to believe that she did so without malice, incidentally), but that she compiled a dossier on Farage in the first place — and then “error of judgment” is hardly a sufficient term on what was a blatant and even wicked attempt at instituting a form of totalitarianism.

This raises the question of whether one can be wicked without intending to be so, for it is quite clear that Ms. Rose had no real understanding, even after her resignation, of the sheer dangerousness and depravity of what the bank, under her direction, had done.

As for the board’s somewhat convoluted declaration that “after careful consideration, it concluded that it retains full confidence”, etc., it suggests that it was involved in an exercise of psychoanalytical self-examination rather than of an objective state of affairs: absurd, in the light of Ms. Rose’s resignation within twenty-four hours. The board, no more than Ms. Rose herself, understood what the essence of the problem was. For them, if there had been no publicity, there would have been no problem: so when Mr. Farage called for the dismissal of the board en masse, I sympathised with his view.

August 13, 2023

August 12, 2023

QotD: Scientific management and the work-to-rule reaction

Scientific management, a.k.a. “Taylorism”, was all the rage around the turn of the 20th century. At its crudest (and I’m only exaggerating a little), you’ve got some dork with a stopwatch and a camera standing behind you while you do your job, and after some observations and a little math, the dork tells you you’re pulling the lever wrong. There’s a scientifically optimized way to pull that lever, one that shaves 0.6 seconds off each of your work “processes”, and henceforth you shall be required to do this exact sequence of steps, every time … and if you disagree, too bad, why do you hate science? Similar regulations follow, until the whole plant is “scientifically” optimized.

And since this is the great age of “Progress”, you’ve got umpteen government regulations to deal with now, too. And then as now, the august personages in Congress wouldn’t dream of soiling even their shoes, let alone their hands, by going anywhere near anyplace labor is actually performed, so all these regulations have been promulgated ex cathedra. Suddenly the straightforward, mindless job of lever-pulling — the one that was already so insulting to the human spirit, so “alienating”, as Marx put it, something to be endured because one has no choice — is bound up with reams of regulations, too. If you don’t like it, build your own factory.

But in this, the workers saw opportunity. You’re going to tell me how to do my job? Fine, but you’d better tell me how to do all of it. Is there anything the Policies and Procedures manual leaves unexplained? Where to place my feet as I stand in front of the lever, for example? I’d better not do anything until the manager tells me exactly what to do, in writing, in a fully-vetted update to the P&P, and have you run that by Compliance, sir? Perhaps the lawyers in the Environmental Division should take a gander, too, since who knows what might contribute to Global Warm … errrrr, whatever, you get the point. It turns out that even back then, when there was no such thing as OSHA or the EPA or the rest of the Federal alphabet soup, the “scientific managers”, let alone Congress, simply weren’t able to envision the nuances of everyone’s day-to-day job. Or, for that matter, the very basics of everyone’s job. Work ground to a halt because everyone was following the rules.

Severian, “A History Lesson”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-01-14.