Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 22 Aug 2023

(more…)

December 8, 2023

The Real Betty Crocker’s Pineapple Upside Down Cake

December 2, 2023

Joe Biden solves the inflation problem, fat!

Like any lying dog-faced pony soldier would know, it’s as easy as saying “Trunalimunumaprzure“:

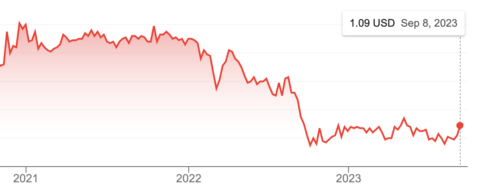

Inflation is kicking just about everyone in the junk here lately, regardless of whether that junk is an innie or an outie. It’s been rough on a lot of us, but I know just how hard it’s been on me and mine.

Prices are up significantly over the last few years and my income isn’t up nearly as much. This creates issues with our finances. The upside is that it’s forced me to be better with money.

But prices are still higher than Willie Nelson on a SpaceX flight.

Luckily, President Joe Biden has figured out the solution to all our problems. He’s going to just tell companies to drop prices.

This week, the White House announced the launch of a Council on Supply Chain Resilience, created with the hope to “strengthen America’s supply chains” and “lower costs for families.”

…

President Joe Biden delivered remarks from the White House on Monday to announce the new council’s creation. He touted the lower inflation rate and falling grocery prices but admonished American companies for, in his view, not going far enough.

“Let me be clear: To any corporation that has not brought their prices back down — even as inflation has come down, even as supply chains have been rebuilt — it’s time to stop the price gouging,” Biden warned, imploring them to “giv[e] the American consumer a break.”

Here’s the issue, at least as I see it.

At Thanksgiving, it was noted here that prices are nearly 20 percent higher than in 2019. This while inflation has supposedly decreased. Prices are still high because it’s not so much that inflation has fallen but that the rate of inflation’s increase has fallen. It doesn’t mean prices should drop, only that they should increase at a slower rate.

December 1, 2023

QotD: The OODA loop

There was a fighter pilot named John Boyd who became the most important strategic theorist writing in English during the 20th century. He began with E/M (energy-maneuverability theory), which became the basis on which modern fighter aircraft are designed and modern fighter tactics taught. He ended his career as one of the architects of the winning “left-hook” strategy in the 1991 Gulf War. Connecting these was a general theory of military effectiveness (and more generally, organizational effectiveness) centered around what he called the OODA loop.

OODA theory is worth reading about in more depth for anyone interested in … well, any kind of competitive dynamics, actually – military, commercial, individual, anything. The Wikipedia article is a good start. Stripped to its essentials, the theory is that competing entities have to go through repeated iterations of observing conditions, relating observation to a generative theory, deciding what option to pursue, and acting. Victory tends to go to the competitor who can run this cycle the fastest.

OODA theory was originally generalized from the observation that in fighter design, maneuverability (especially a shorter turning radius) beats straight-line speed. When you get inside your opponent’s OODA loop, either physically or conceptually, you can attack him from unexpected angles. You can be where he isn’t. You have the initiative; he is reduced to reacting, often with too little and too late.

Eric S. Raymond, “The Smartphone Wars: Tightening the OODA Loop”, Armed and Dangerous, 2011-02-18.

November 30, 2023

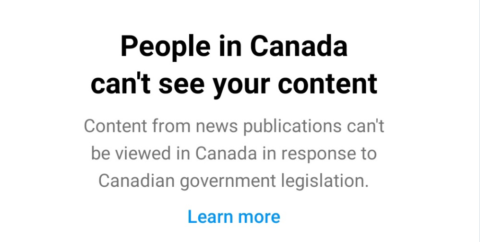

Canadian government declares victory over Google, then lays down its arms and marches into captivity

The Trudeau government has won a glorious, historic victory over the evil capitalistic powers of Google in the war of Bill C-18. Let all patriotic Canadians raise their hands to cheer our victorious politicians before they have to admit out loud that they fucked up real good:

Heritage Minister Pascale St. Onge has surrendered to Google and Canadian media have avoided what would have been a catastrophic exclusion from the web giant’s search engine.

In the short term, this is very good news. The bureaucrats at Heritage must have performed many administrative contortions to find the words needed in the Online News Act‘s final regulations to satisfy Google, a beast which isn’t easily soothed. In doing so, they have managed to avoid what Google was threatening — to de-index news links from its search engine and other platforms in Canada. Given that Meta had already dropped the carriage of news on Facebook and Instagram in response to the same legislation, Google’s departure would have constituted a kill shot to the industry.

Instead, the news business will get $100 million in Google cash. For this, all its members will now fight like so many pigeons swarming an errant crust of bread.

The agreement will also allow the government, while surrounded by an industry whose reputation and economics have been devastated by this policy debacle, to attempt to declare victory. Signs of that are already evident.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that while 100 million bucks is nothing to sneeze at, in the grand scheme of things it is a drop in the bucket for an industry in need of at least a billion dollars if it is to recover any sense of stability. Indeed, when News Media Canada first began begging the government to go after Google and Meta for cash, some involved were selling the idea that sort of loot was possible.

This did not turn out to be so.

Instead of the $100,000 per journo cashapalooza that was once hoped for, the final tally will be more like $6,666.00 per ink-stained wretch.

That figure is based on two assumptions. The first is that the government has agreed to satisfy Google’s desire to pay a single sum to a single defined industry “collective” that would then divide the loot on a per-FTE (full-time employee) basis to everyone granted membership in the industry’s bargaining group. Google had made it clear it had no interest in conducting multiple negotiations and exposing itself to endless and costly arbitrations. So, as we have a deal and Google held all the cards, it’s fair to assume it got what it wanted — a single collective with a single agreement and a single cheque.

November 27, 2023

The slackening pace of technological innovation

Freddie deBoer thinks we’re living off the diminishing fumes of a much more innovative and dynamic era:

I gave a talk to a class at Northeastern University earlier this month, concerning technology, journalism, and the cultural professions. The students were bright and inquisitive, though they also reflected the current dynamic in higher ed overall – three quarters of the students who showed up were women, and the men who were there almost all sat moodily in the back and didn’t engage at all while their female peers took notes and asked questions. I know there’s a lot of criticism of the “crisis for boys” narrative, but it’s often hard not to believe in it.

At one point, I was giving my little spiel about how we’re actually living in a period of serious technological stagnation – that despite our vague assumption that we’re entitled to constant remarkable scientific progress, humanity has been living with real and valuable but decidedly small-scale technological growth for the past 50 or 60 or 70 years, after a hundred or so years of incredible growth from 1860ish to 1960ish, give or take a decade or two on either side. You’ve heard this from me before, and as before I will recommend Robert J. Gordon’s The Rise & Fall of American Growth for an exhaustive academic (and primarily economic) argument to this effect. Gordon persuasively demonstrates that from the mid-19th to mid-20th century, humanity leveraged several unique advancements that had remarkably outsized consequences for how we live and changed our basic existence in a way that never happened before and hasn’t since. Principal among these advances were the process of refining fossil fuels and using them to power all manner of devices and vehicles, the ability to harness electricity and use it to safely provide energy to homes (which practically speaking required the first development), and a revolution in medicine that came from the confluence of long-overdue acceptance of germ theory and basic hygienic principles, the discovery and refinement of antibiotics, and the modernization of vaccines.

Of course definitional issues are paramount here, and we can always debate what constitutes major or revolutionary change. Certainly the improvements in medical care in the past half-century feel very important to me as someone living now, and one saved life has immensely emotional and practical importance for many people. What’s more, advances in communication sciences and computer technology genuinely have been revolutionary; going from the Apple II to the iPhone in 30 years is remarkable. The complication that Gordon and other internet-skeptical researchers like Ha-Joon Chang have introduced is to question just how meaningful those digital technologies have been for a) economic growth and b) the daily experience of human life. It can be hard for people who stare at their phones all day to consider the possibility that digital technology just isn’t that important. But ask yourself: if you were forced to live either without your iPhone or without indoor plumbing, could you really choose the latter? I think a few weeks of pooping in the backyard and having no running water to wash your hands or take a shower would probably change your tune. And as impressive as some new development in medicine has been, there’s no question that in simple terms of reducing preventable deaths, the advances seen from 1900 to 1950 dwarf those seen since. To a remarkable extent, continued improvements in worldwide mortality in the past 75 years have been a matter of spreading existing treatments and practices to the developing world, rather than the result of new science.

ANYWAY. You’re probably bored of this line from me by now. But I was talking about this to these college kids, none of whom were alive in a world without widespread internet usage. We were talking about how companies market the future, particularly to people of their age group. I was making fun of the new iPhone and Apple’s marketing fixation on the fact that it’s TITANIUM. A few of the students pushed back; their old iPhones kept developing cracks in their casings, which TITANIUM would presumably fix. And, you know, if it works, that’s progress. (Only time and wear and tear will tell; the number of top-of-the-line phones I’ve gone through with fragile power ports leaves me rather cynical about such things.) Still, I tried to get the students to put that in context with the sense of promise and excitement of the recent past. I’m of a generation that was able to access the primitive internet in childhood but otherwise experienced the transition from the pre-internet world to now. I suspect this is all rather underwhelming for us. When you got your first smartphone, and you thought about what the future would hold, were your first thoughts about more durable casing? I doubt it. I know mine weren’t.

Why is Apple going so hard on TITANIUM? Well, where else does smartphone development have to go? In the early days there was this boundless optimism about what these things might someday do. The cameras, obviously, were a big point of emphasis, and they have developed to a remarkable degree, with even midrange phones now featuring very high-resolution sensors, often with multiple lenses. The addition of the ability to take video that was anything like high-quality, which became widespread a couple years into the smartphone era, was a big advantage. (There’s also all manner of “smart” filtering and adjustments now, which are of more subjective value.) The question is, who in 2023 ever says to themselves “smartphone cameras just aren’t good enough”? I’m sure the cameras will continue to get refined, forever. And maybe that marginal value will mean something, anything at all, in five or ten or twenty years. Maybe it won’t. But no one even pretends that it’s going to be a really big deal. Screens are going to get even more high-resolution, I guess, but again – is there a single person in the world who buys the latest flagship Samsung or iPhone and says, “Christ, I need a higher resolution screen”? They’ll get a little brighter. They’ll get a little more vivid. But so what? So what. Phones have gotten smaller and they’ve gotten bigger. Some gimmicks like built-in projectors were attempted and failed. Some advances like wireless charging have become mainstays. And the value of some things, like foldable screens, remains to be seen. But even the biggest partisans for that technology won’t try to convince you that it’s life-altering.

November 26, 2023

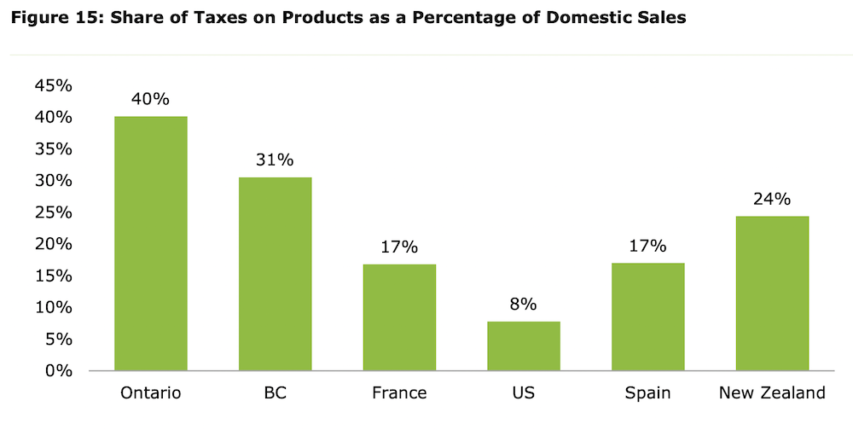

Ontario’s beer market may see radical changes soon

For beer drinkers outside Ontario, the province’s weird beer retailing rules may seem to be from a different time, but that’s only because they are. Until fairly recently, the only place to buy beer was from one of two quasi-monopoly entities: the provincially owned and operated LCBO or the foreign brewery owned Beer Store. LCBO outlets were limited to single containers and six-packs, while Beer Stores sold larger multipacks and also handled bottle deposits and returns. In the last few weeks, the Ontario government has indicated that long overdue changes are coming:

“The Beer Store” by Like_the_Grand_Canyon is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The only thing we really know at this point (and it’s been reported by the Toronto Star and now CBC, and earlier by this website, all from sources) is the horribly unfair deal The Beer Store has had since 1927 in Ontario is about to come to an end. It’s expected that The Beer Store will be given notice by the end of December under the Master Framework Agreement (MFA) that the deal will be all but dead. They will have two years to wrap things up while a more modern system of booze retailing is fine-tuned and prepared for implementation. There’s a new era dawning in Ontario, one that would seemingly benefit grocery and convenience stores, local brewers, Ontario wineries, and obviously consumers who will get wider selection, more convenience and competitive pricing.

“The MFA has never been about choice, convenience or prices for customers, it has always been about serving the interests of the big brewing conglomerates, and that’s what needs to be addressed,” Michelle Wasylyshen, spokesperson for the Retail Council of Canada, whose board of directors includes members from Loblaw, Sobeys, Metro, Walmart, and Costco, told Mike Crawley of the CBC.

The end of The Beer Store MFA in whatever iteration it will look like will have a cascading impact on local VQA wine. Ontario wineries hope that it’s a positive impact and are cautiously optimistic that wide open beer and wine sales at grocery and convenience stores means more sales and less levies for their products.

As the CBC pointed out in its story, the looming reforms “pit a range of interests against each other, as big supermarket companies, convenience store chains, the giant beer and wine producers, craft brewers and small wineries all vie for the best deal possible when Ontario’s almost $10-billion-a-year retail landscape shifts. And — this is a biggie — the LCBO lobbying efforts to keep its antiquated system of monopoly retailing intact, which seems to be a big ask with what we now know from sources. Something must give.

Some key bullet points from the CBC report:

- Will the government shrink the LCBO’s profit margins, including its take from products that other retailers sell?

- Will retailers such as grocery and convenience stores be required to devote a certain amount of shelf space to Ontario-made beer and wine, or will they have total control over the inventory they stock?

- Will small Ontario wineries get any help in competing against big Ontario wineries whose products can contain as much as 75% imported wine?

The government has been listening to all stakeholders in the booze industry in Ontario for over a year now. Three key associations — Ontario Craft Wineries, Tourism Partnership Niagara, and Wine Growers Ontario — joined together to commission a report titled Uncork Ontario. That report, which concludes that the Ontario wine sector is well positioned to drive sustainable economic growth for the region, the province, and the country and has the potential to drive at least $8 billion in additional real GDP over the next 25 years, launched a campaign to lobby the government for radical changes to reach those lofty goals, or at least put the wheels in motion.

One of the big issues for Ontario wineries is a punishing 6.1% “sin” tax charged on every wine made in Ontario but not foreign wines. It’s a tax that’s been hurting Ontario wineries for years even though a grant was issued to wineries to help pay that tax back. To this date, the tax has not been cancelled and wineries keep remitting the tax owed monthly and can only hope the grant keeps getting extended. Ontario wines are among the highest taxed in the world with up to 73% of every bottle sold going to taxes and severe levies at the LCBO.

November 24, 2023

More than 1,500 new jobs thanks to federal and provincial subsidies … except the jobs are for South Koreans

Tristin Hopper applauds the great job creation scheme that the federal and Ontario governments have put in place … if you ignore the inconvenient fact that most of the newly created jobs aren’t even going to Canadians:

When the Ontario and federal governments greenlit one of the biggest corporate subsidy payouts in Canadian history last summer, their main pitch was the deal would create jobs.

“The governments of Canada and Ontario are partnering to attract once-in-a-generation projects that will anchor our auto manufacturing sector and keep good jobs in Canada,” reads the opening line of a July 6 joint statement announcing a record-breaking $28 billion in government “performance incentives” to secure two foreign-owned EV battery factories in Southern Ontario.

The subsidy-per-job ratio was never great. Even according to the most optimistic estimates of government spokespeople, the two factories — one operated by Volkswagen, the other by Stellantis — would create about 5,500 jobs. Per job, that’s roughly $5 million in lifetime subsidies and tax credits.

But now, it appears that many of those jobs may not even go to Canadians.

Last week, during a visit by South Korean Ambassador Woongsoon Lim to Windsor, Ont., a social media post by the Windsor Police casually mentioned that “1,600 South Koreans” would soon be arriving in the community to staff the Stellantis plant, which is set to open next year.

With the new LGEngergy Solutions battery plant being built, we expect approximately 1,600 South Koreans traveling to work and live in our community in 2024.

— Windsor Police (@WindsorPolice) November 16, 2023

The CEO of NextStar — the Stellantis joint venture operating the factory — hasn’t confirmed the 1,600 figure, but said in a statement that the “equipment installation phase of the project requires additional temporary specialized global supplier staff”. He added that the company was “committed” to hiring Canadians to fill the 2,500 full-time jobs at the completed plant

The revelation has sparked a wave of confusion and finger-pointing among the very officials who, mere months ago, were championing the plant as an unalloyed triumph for Canadian manufacturing jobs.

When the subsidy arrangement was first announced in July, Ontario Economic Development Minister Vic Fedeli called it a “historic deal” and “a great agreement” that “protects the thousands of jobs quite frankly that were at stake”.

November 22, 2023

Marginal Thinking and the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Marginal Revolution University

Published 1 Aug 2023Thinking on the margin is one of the most fundamental concepts in economics – and a valuable everyday tool for making optimal decisions.

For such an important idea, the meaning of marginal thinking is surprisingly simple: when faced with a decision, you should compare the marginal benefit of a possible action to its marginal cost. If the marginal benefit is greater than the marginal cost, do it!

Marginal thinking is best illustrated by some examples of everyday decisions. The volume you choose when you watch TV, the pricing strategy of a clothing shop, or even the decision to walk out of a boring film are all informed by marginal thinking.

The “Sunk Cost Fallacy” is a common failure to apply marginal thinking. Focusing on past decisions – the price we paid for an item, the time we’ve already invested in a relationship – can lead us astray. We can’t change the past, so only the potential marginal benefit and marginal cost of the next possible action are relevant to decision-making.

(more…)

November 21, 2023

“Self-checkouts are not quite Skynet T-800 death dealers. Sarah Connor can rest easy – for now”

I realize the problem is me, in that I hate self-checkout kiosks with a fiery passion and have been known to abandon any plans to purchase from a store if there is no human assigned to the checkout desk. I decline (with thanks) all offers to use the self-checkout — several of which are often unused — while lined up three or four deep at the one human’s work station. It must be my Luddite side showing. But, as Christopher Gage shows here, I’m not completely alone:

Self-checkout using NCR Fastlane machines at a Sainsbury’s store in the UK.

Photo by Magnus Manske via Wikimedia Commons.

“He’s got a problem with potatoes,” said the condemned, guarding the self-checkout machines. Potatoes plague them. Carrier bags flummox them. ‘Surprising item on the scale,’ it squeaked as if I were weighing up a kilo of black-tar heroin.

The retirement refusenik tapped a code on the screen for the third occasion before returning to his post. ‘Unexpected item in the bagging area.’ Embarrassed, I marshalled my friend — the Hobbity, amenable man with the silver slugs for eyebrows — for the fourth time. He recanted a well-worn sop dispensed to young dotards like me: “Don’t take it personally,” he said. “He just doesn’t like you.”

Self-checkouts are not quite Skynet T-800 death dealers. Sarah Connor can rest easy — for now.

After a little while, the machine let me go. The ordeal, fractious and infinitely slower than employing the helpful man to man a till, was over. Then, the devil-device sucker-punched square in the testes.

“Lovely to see you bye for now,” read the screen. Sinister, like a Jehovah’s Witness grinning. No comma after the introductory clause?! The insolent swine. I fought the primal urge to drown the machine in Coca-Cola and watch it crackle. The clean-up would be Harold’s job. He had enough on his plate.

Mercifully, one supermarket has sacked these silly machines.

Booths, a posh retailer up north, has retired self-checkouts in all but two of their stores. The good burghers of Booths reckon humans talking to other humans is a groundbreaking idea that will catch on in future.

“We have based this not only on what we feel is the right thing to do but also from having received feedback from our customers,” they said.

“Delighting customers with our warm northern welcome is part of our DNA.”

Wearily, Booths did what British northerners must do lest they spontaneously combust — they peacocked their northernness. Apparently, to be born on a particular patch of this floating rock bestows northerners an umbilical, friendly mien.

Northerners cannot help themselves. POV: You encounter a northerner in a pub: “A malignant tumour, you say? You wanna get yourself a northern tumour. Northern tumours are far less aggressive than those bloody southern tumours. It’s a fact! Northern tumours still have a sense of community, you see. Not like southern tumours …”

I must forgive them. Booth’s “northern welcome” is a good thing. Entities imbued with DNA are a good thing. Even one fewer self-service checkout is a good thing.

From where Booth’s tread, others may follow. The numbers don’t tell fibs.

Self-checkouts mutate even the most cherubic of citizens into a degenerate thief. Stores with self-service checkouts suffer double the shrinkage (4%) — industry-speak for pilfering and thieving.

Researchers say the temptation can prove too much, provoking our inner tea leaf into a spot of half-inching. Self-checkouts goad miscreants into slapping a “Reduced to £1” sticker on a litre of Jameson.

Booths have bucked a trend. A fatuous, anti-human trend.

Update: Fixed broken URL.

QotD: Collabortage

Yes, that’s a new word in the blog title: collabortage. It’s a tech-industry phenomenon that needed a name and never had one before. Collabortage is what happens when a promising product or technology is compromised, slowed down, and ultimately ruined by a strategic alliance between corporations that was formed (at least ostensibly) to develop it and bring it to market.

Collabortage always looks accidental, like a result of exhaustion or management failure. Contributing factors tend to include: poor communication between project teams on opposite sides of an intercorporate barrier, never-resolved conflicts between partners about project objectives, understaffing by both partners because each expects the other to do the heavy lifting, and (very often) loss of internal resource-contention battles to efforts fully owned by one player.

Occasionally the suspicion develops that collabortage was deliberate, the underhanded tactic of one partner (usually the larger one) intended to derail a partner whose innovations might otherwise have disrupted a business plan.

Eric S. Raymond, “Collabortage”, Armed and Dangerous, 2011-02-16.

November 15, 2023

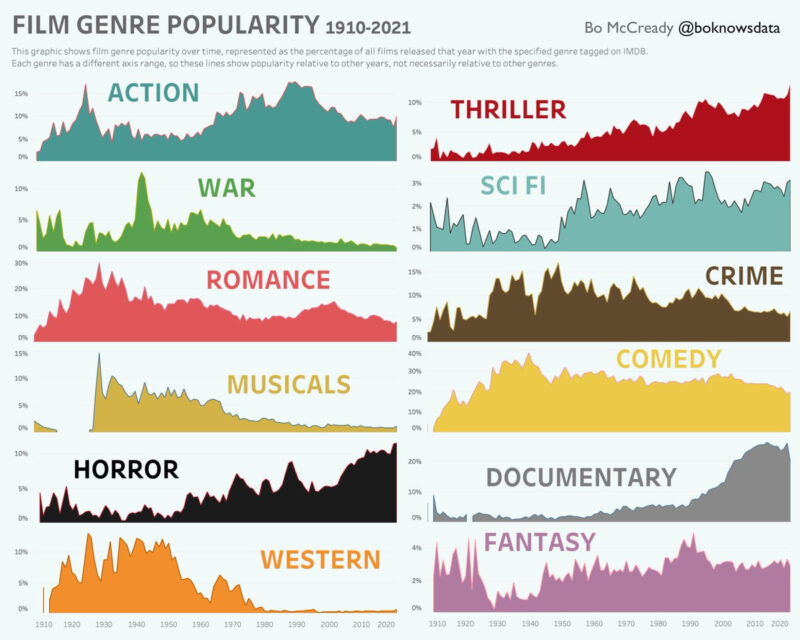

The big brains of Hollywood display “a special kind of stupid”

Ted Gioia met with a group of executives from movie distribution firms outside the North American market back in 2016. It was a good time, financially, but the overall tone of the meeting was anxious because the trend seemed unsustainable:

These were smart people, but they didn’t make the movies. They just ran theater chains. But they didn’t need to be specialists in creativity or storytelling to know that hit films were now built on tired formulas, the same plot lines played out over and over again.

Special effects added some sizzle to the steak, but it was still the same stale meal night after night. Sooner or later, even superheroes die.

Other genres have come and gone — westerns and musicals and other box office draws of the past. Comic book franchises would eventually meet the same fate.

Source: Bo McReady

Back then, Disney was bragging to shareholders that another 20 Marvel films were already in the pipeline. And that was just a start. CEO Bob Iger explained that Disney owned the rights to 7,000 different Marvel characters — implying that brand franchises could propagate forever, like copulating Australian bunnies.

That was the party line in Burbank. But most of the people I spoke to that day privately expressed doubts about this formula-driven strategy. They hoped to enjoy a few more years of boom times, but worried about what would happen next.

“It takes a special kind of stupid to kill off Indiana Jones or Toy Story or a Marvel superhero, but that’s exactly what’s playing out right now in the Magic Kingdom.”

As it turned out, they were right to worry. But a virus, not a superhero, let them down. The first COVID case happened almost exactly three years after my December 2016 talk.

But it now looks like the pandemic merely delayed the creative collapse.

Hollywood has saturated the market with look-alike movies. Their pipeline of films is now exploding like the Nord Stream, but with this difference—studios are still sitting on a huge pile of future bombs.

And what does a studio do with a bomb on its hands?

They have four options—and they are four kinds of ugly

- You delay the film, hoping for a better market environment in the future.

- You send it back for rewriting and more filming

- You cancel it entirely, and write off the investment

- You release it — sinking another $50 million, more or less, into marketing — and then watch it collapse at the box office.

Disney is getting a sour taste of strategy number four this week.

November 10, 2023

Only a government could waste this much money on the ArriveCAN boondoggle

Chris Selley is in two minds about the ArriveCAN scandal, in that thus far no minister has been implicated but we all may naively assume that the civil service was better than this sort of sleaze:

It’s tempting to want to forget that ArriveCAN, the federal government’s pandemic travel app that collected dead-simple information from arriving travellers and forwarded it to relevant officials for scrutiny, and that somehow cost $54.5 million — a figure no one has come within 100 miles of justifying, and don’t let anyone tell you differently. No one wants to remember the circumstances that supposedly made ArriveCAN necessary.

One could also certainly argue there are aspects of Canada’s pandemic response more desperately needing scrutiny. So, so many aspects.

But whenever the House of Commons operations committee sits down to investigate ArriveCAN, there are fireworks. And you start to think, maybe this godforsaken app is more key to understanding Canada’s pandemic nightmare than you first thought.

The latest blasts came on Tuesday, when Cameron MacDonald, director-general of the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) when the pandemic hit, alleged Minh Doan, then MacDonald’s superior and since promoted to chief technological officer of the entire federal government — pause for thought — had lied to the committee on Oct. 24 with respect to who picked GCStrategies to oversee the ArriveCAN project.

Doan told the committee he hadn’t been “personally involved” in the decision. MacDonald, who says he had recommended Deloitte build the app, says that’s garbage. “It was a lie that was told to this committee. Everyone knows it,” he said. “Everyone knew it was his decision to make. It wasn’t mine.” MacDonald said Doan had threatened in a telephone conversation to finger him as the culprit, and that he had felt “incredibly threatened”.

Crikey.

For those who’ve blissfully forgotten, GCStrategies consists of two people who subcontract IT work to teams of experts and takes a cut off the top — in this case a cut of roughly $11 million, for an app that should have cost a fraction of that, if it was to exist at all. Needless to say, that wasn’t the only fat contract GCStrategies — which, again, is two men and an address book — had received from the government over the years. Each GCStrategist made more money off ArriveCAN than I’ll likely make in my life. It makes me want to strap on a bass drum and sing “The Internationale” in public.

October 30, 2023

The rapidly fading market for “song investing”

Ted Gioia called it over two years ago, and now it’s coming true:

The collapse finally came.

When I analyzed the song buyout mania, led by the Hipgnosis fund, back in June 2021, I predicted that this ultra-hot investment trend would “come to an unhappy end”. And now the collapse has arrived.

We’ve reached the endgame. The song fund’s share price has dropped 50% since I made that assessment — and now shareholders have voted to dissolve or reorganize the investment trust.

But where do we go from here? What are old songs really worth? And who will end up owning all these old rock and pop tunes?

Below I offer 12 predictions.

Much of what I have to say is harsh. That’s unfortunate — if I were a real judge, I’d err on the side of leniency. It’s never fun issuing such hardass verdicts. But if I claim to be the Honest Broker, I really have to stick with truths, even when (as in this case) they’re painful truths.

(1) Many musicians still want to sell their songs, but it will be hard to find generous buyers.

Bob Dylan got out at the top, but the times are now a-changin’. Musicians won’t get the big payouts available back in 2021. A telltale sign will be more deals with “undisclosed terms” — because nobody will want to brag about these lowball transactions.(2) Professional financiers have finally learned their lesson.

The two big finance outfits promoting song investing, Hipgnosis and Round Hill, have faltered and will now sell the songs they bought. Sophisticated investors no longer believe the hype. So don’t expect to see the launch of new song investment funds any time soon. The remaining buyers will be bottom fishers and the terminally naive (described in more detail below).[…]

(5) Look out for these vultures in all sectors of the music business.

When private equity firms knock on your door, it’s a sign that you’re already half dead. These folks actually enjoy picking on carcasses — which is easier work than hunting for live prey. I tend to avoid name-calling, but there’s a reason why some folks refer to them as vulture capitalists. That’s their specialty and their economic model is built on bottom-feeding. This is why private equity firms bought up lots of failing local newspaper, struggling local radio stations, etc. Guess what’s next on their list? Expect to see these tough hombres play a bigger role in all aspects of the music business over the next decade.[…]

(7) This whole situation is a case study in misallocated investment capital.

There’s a general lesson here too. I realized, early on in my consulting work, that the single biggest mistake large corporations make is investing too much to keep their old business units alive — when they would be wiser putting that cash to work in new opportunities. The major record labels in the current moment are poster children for exactly this mistaken sense of priorities. They will support the “old songs” business model at all costs — it’s a core part of their self image — but return on investment will be dismal.

October 21, 2023

“… we’re not a business publication. One of them can point out that corporate governance is a joke in Canada”

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte reviews a recent BNN Bloomberg interview with Heather Reisman former-and-now-current-again CEO of Canada’s only big box book retailer, Indigo:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

Heather Reisman gave an interview to Amanda Lang of BNN Bloomberg last week, her first effort to explain a summer of screwball management at Canada’s only bricks-and-mortar book chain.

[…]

How did Heather explain the zany sequence of events that started with her reporting Indigo’s fourth massive annual loss in five years in May; saw her booted in June from her role as executive chairman of Indigo, the company she founded, by her husband and controlling shareholder, Gerry Schwartz, along with every member of the board of directors who wasn’t personally beholden to Gerry; saw her spin her exit as a personal life-stages choice (“deciding when it is time to move on is one of the toughest decisions a founder must make”); saw her hand-picked successor and CEO, long-time British clothing retailer Peter Ruis, grab a seven-figure payout and make his own exit in September; saw the company announce that it would “act swiftly to find the right leader to move the company forward following Peter’s resignation”; saw Heather reinstated at the head of the chain two weeks later?

She didn’t. How could anyone explain that?

Heather bullshitted her way through the interview. It was all Ruis’s fault, she told Amanda. Indigo “took a journey off brand” under Ruis. She’d put him in charge of a book chain and “suddenly I was hearing that we were getting famous for selling $550 barbecues,” she said. “Somehow vibrators turned up in our stores and I remember saying ‘no, that’s not who we are.'” Ruis had “lost sight of … what our commitment is to customers.” He was “taking the business in the wrong direction” and it was showing up in the financials.

Heather claimed she’d been powerless to stop Ruis: “I was gone formally for over a year and informally for two and a half years in the sense that I was pulling back and not able to influence things.”

I scarcely know where to start. We could talk about the breathtaking ease with which Heather presented herself as a victim of Ruis while running him over with a forklift. How she hired a career fashion retailer to run what most Canadians still understand as a book chain and complained that he took the business off brand. How his barbecues and dildo merchandising was a logical extension of the cheeseboards and blankets merchandising she’d been doing for a decade.

If we were a serious business publication, we’d have to talk about her supposed powerlessness to do anything about the dildo-happy Ruis. The people who run public companies have duties to their shareholders, one of which is to keep them informed—promptly, honestly, transparently—about the management of the business. If Heather was gone “formally for over a year” and “informally for two and a half years,” investors should have known, right?

Let’s start with “formally for over a year.” Heather is referring to the most recent period of September 2022 to August 2023 during which Barbecue Boy was CEO of the company. Was Heather gone?

She was no longer CEO, a title she’d held for a quarter century, but according to corporate records she remained executive chairman of Indigo during that time, drawing an annual salary of almost a million. Titles matter in public companies. The difference between an executive chairman and a run-of-the-mill chairman is that the former is recognized as having an active role in the operations of the business, hence the executive-level salary. Executive chairman is higher on the org chart than CEO. If the company was moving off brand, betraying its customers, she was the one person with the formal role and the moral authority, as founder, to send the “four hours of fun” Firefighter Vibrator from Smile Makers ($75.00) back to the warehouse. Either Heather misspoke to Amanda last week about being “gone” or she spent her last year at Indigo misrepresenting herself to her shareholders and drawing a salary under false pretenses.