In Quillette, Nigel Biggar recounts how he was conscripted into the Imperial History Wars:

It was December 2017, and my wife and I were at Heathrow airport, waiting to board a flight to Germany. Just before setting off for the departure gate, I could not resist checking my email one last time. My attention sharpened when I saw a message in my inbox from the University of Oxford’s Public Affairs Directorate. What I found was a notification that my “Ethics and Empire” project, organized under the auspices of Oxford’s McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics & Public Life, had become the target of an online denunciation by a group of students; followed by reassurance from the university that it had risen to defend my right to run such a thing.

So began a weeks-long public row that raged over the project, which had “gathered colleagues from Classics, Oriental Studies, History, Political Thought, and Theology in a series of annual workshops to measure apologias and critiques of empire against historical data from antiquity to modernity across the globe.” Four days after I flew, the eminent imperial historian who had conceived the project with me abruptly resigned. Within a week of the first online denunciation, two further ones appeared, this time manned by professional academics, the first comprising 58 colleagues at Oxford, the second, about 200 academics from around the world. For over a fortnight, my name was in the press every day.

What had I done to deserve all this unexpected attention? Three things. In late 2015 and early 2016, I had offered a partial defence of the late-19th-century imperialist Cecil Rhodes during the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in Oxford. Then, in late November 2017, I published a column in the Times, in which I referred approvingly to Bruce Gilley’s controversial article “The Case for Colonialism”, and argued that the British (along with Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders) have reason to feel pride as well as shame about their imperial past. Note: pride, as well as shame. And a few days later, third, I finally got around to publishing an online account of the “Ethics and Empire” project, whose first conference had in fact been held the previous July.

Contrary to what the critics seemed to think, the Ethics and Empire project is not designed to defend the British Empire, or even empire in general. Rather, it aims to select and analyse evaluations of empire from ancient China to the modern period, in order to understand and reflect on the ethical terms in which empires have been viewed historically. A classic instance of such an evaluation is St Augustine’s The City of God, the early-fifth-century AD defence of Christianity, which involves a generally critical reading of the Roman Empire. Nonetheless, Ethics and Empire was conceived with awareness that the imperial form of political organisation was common across the world and throughout history until 1945; and so does not assume that empire is always and everywhere wicked; and does assume that the history of empires should inform — positively, as well as negatively — the foreign policy of Western states today.

The territories that were at one time or another part of the British Empire. The United Kingdom and its accompanying British Overseas Territories are underlined in red.

Composed by “The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick” via Wikimedia Commons.Thus did I stumble, blindly, into the Imperial History Wars. Had I been a professional historian, I would have known what to expect, but being a mere ethicist, I did not. Still, naivety has its advantages, bringing fresh eyes to see sharply what weary ones have learned to live with.

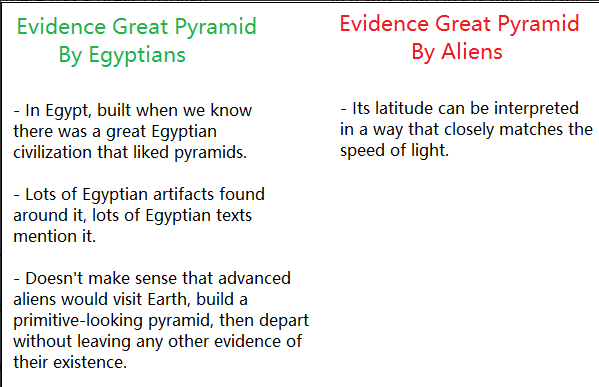

One surprising thing I have seen is that many of my critics are really not interested in the complicated, morally ambiguous truth about the past. For example, in the autumn of 2015, some students began to agitate to have an obscure statue of Cecil Rhodes removed from its plinth overlooking Oxford’s High Street. The case against Rhodes was that he was South Africa’s equivalent of Hitler, and the supporting evidence was encapsulated in this damning statement: “I prefer land to n—ers … the natives are like children. They are just emerging from barbarism … one should kill as many n—ers as possible.” As it turns out, however, initial research discovered that the Rhodes Must Fall campaigners had lifted this quotation verbatim from a book review by Adekeye Adebajo, a former Rhodes Scholar who is now director of the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg. Further digging revealed that the “quotation” was, in fact, made up from three different elements drawn from three different sources. The first had been lifted from a novel. The other two had been misleadingly torn out of their proper contexts. And part of the third appears to have been made up.

There is no doubt that the real Rhodes was a moral mixture, but he was no Hitler. Far from being racist, he showed consistent sympathy for individual black Africans throughout his life. And in an 1894 speech, he made plain his view: “I do not believe that they are different from ourselves.” Nor did he attempt genocide against the southern African Ndebele people in 1896 — as might be suggested by the fact that the Ndebele tended his grave from 1902 for decades. And he had nothing at all to do with General Kitchener’s concentration camps during the Second Boer War of 1899–1902 (which themselves had nothing morally in common with Auschwitz). Moreover, Rhodes did support a franchise in Cape Colony that gave black Africans the vote on the same terms as whites; he helped to finance a black African newspaper; and he established his famous scholarship scheme, which was explicitly colour-blind and whose first black (American) beneficiary was selected within five years of his death.