When I was in middle school, my favourite teacher was a huge fan of the Leakey family’s discoveries in central Africa, and took every opportunity to show us films on the latest hominid remains uncovered (and by “latest”, it usually meant several years old, as 16mm films distributed through the county school system were rarely all that “new”). I assume she was a frustrated anthropologist herself, honestly, although I found her to be a very good teacher even if she’d “settled” for teaching as a career. In The Iconoclast, Geoffrey Clarfield remembers the late Richard Leakey, “the last Victorian scientist”, who died earlier this month in Kenya:

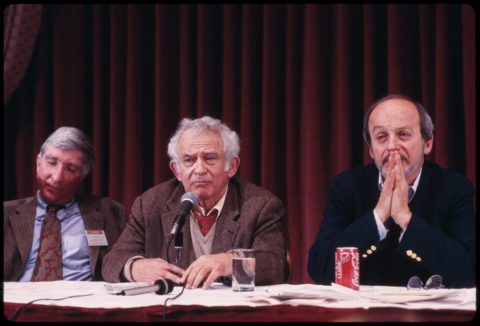

Richard Leakey at the WTTC Global Summit 2015.

Detail of original photo by the World Travel & Tourism Council via Wikimedia Commons.

Kenyan paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey died on January 2nd at age 77, following an extraordinary career devoted to the scientific exploration of human origins. Richard was once my boss. And although we never became friends, I came to know him fairly well.

He died peacefully in his house overlooking Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, where he’d made his most notable discoveries, and which occupied his imagination from an early age until his final days. It was fitting that he was buried beside his home, amid the same terrain from which he’d dug up humanity’s long-buried early ancestors. As I once heard him say to a group of visitors, “You feel instantly at home when you arrive in Kenya because Kenya was once everyone’s home!” (Essayists are supposed to shun exclamation marks, but this was simply the way the man spoke.)

To an outsider, Richard’s work history may appear to comprise a series of disconnected, sometimes testosterone-driven adventures. By turns, he was a wildlife trapper and animal trader, safari guide, bush pilot, gifted (albeit informally trained) fossil hunter, archaeological excavator, scientific autodidact, museum and civil-service administrator, member of parliament, opposition leader, cabinet minister, conservation activist, Kenyan patriot, fundraiser, public speaker, and prolific writer. The public knew him best as a television and film presenter. But those who knew him privately will also remember him as an enthusiastic team leader and mentor of young talent.

In my case, he helped advance my own project to train young Kenyan researchers to record and document traditional music in the northern part of their country, the Turkana District in particular. When I’d raised funds for this initiative, he brought it under the auspices of the National Museums of Kenya (NMK), of which he was then director.

While he may have seemed like something of an (enormously) overachieving dilettante to some, there was in fact a unity to his life and work. The times being what they are, many will focus on the fact that he was a white man taking a prominent role in a largely black country. But in truth, he likely attracted more scrutiny for being a fervent admirer of Charles Darwin, and a secular atheist, in a religious part of the world. He once published his own edited and illustrated version of Origin of Species, which I read when I was working for him, and his contributions to that volume gave me insight into what I believe was his fundamentally edifying professional motivation. I still have it on my shelf.

Richard emphasized that humankind had evolved in the Great Rift Valley, and from there had spread “out of Africa”, as the saying goes. He also believed that a previously underestimated factor in human evolution had been our species’ relationship to evolving biodiversity and prehistoric climate fluctuation — “paleoenvironments” as they came to be called.