TheSnakeCharmer

Published 8 Dec 2021Playing “Auld Lang Syne” on Bagpipes to bid farewell to this year and welcome the new year. “Auld lang syne” lyrics are meaningful that warms the heart up every time, thanks to Robbie Burns. One of the “Auld lang syne” is one of the most popular New Year song. I took inspiration for this by the beautiful versions of Dan Fogelberg. I hope you enjoy and play my version as your Christmas and New Year’s songs.

Stream/Buy the song:

Spotify – https://open.spotify.com/album/2hdC9M…

Apple music – https://music.apple.com/us/album/auld…

Available on all streaming and download platformsFind me on:

Spotify – The Snake Charmer

Instagram – thesnakecharmerbagpiper

Twitter – thsnakecharmerMusic Produced by Karan Katiyar

Filmed by Karan Katiyar

Edited by Archy Jay#Auldlangsyne #Bagpipes #Newyearsong

January 1, 2022

“Auld Lang Syne” on Bagpipes – The Snake Charmer

Merry Olde England

Sebastian Milbank on the often disparaged nostalgic view of “the good times of old England”:

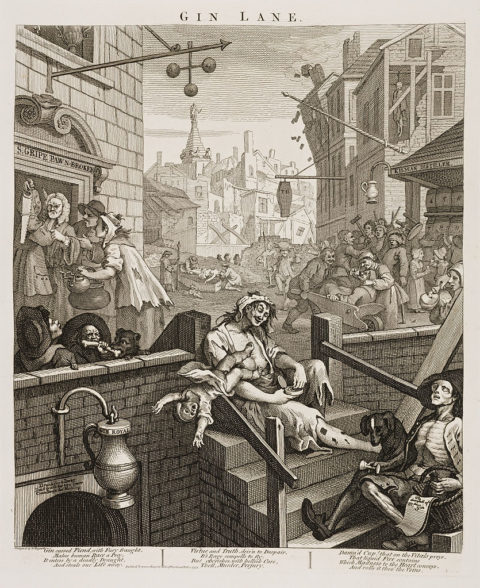

Gin Lane, from Beer Street and Gin Lane. A scene of urban desolation with gin-crazed Londoners, notably a woman who lets her child fall to its death and an emaciated ballad-seller; in the background is the tower of St George’s Bloomsbury.

The accompanying poem, printed on the bottom, reads:

Gin, cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught,

Makes human Race a Prey.

It enters by a deadly Draught

And steals our Life away.

Virtue and Truth, driv’n to Despair

Its Rage compells to fly,

But cherishes with hellish Care

Theft, Murder, Perjury.

Damned Cup! that on the Vitals preys

That liquid Fire contains,

Which Madness to the heart conveys,

And rolls it thro’ the Veins.

Wikimedia Commons.

The decadence and excess of the city is of a piece with puritanical restraint

William Wordsworth wrote:

They called Thee Merry England, in old time;

A happy people won for thee that name

With envy heard in many a distant clime;

And, spite of change, for me thou keep’st the same

Endearing title, a responsive chime

To the heart’s fond belief; though some there are

Whose sterner judgments deem that word a snare

For inattentive Fancy, like the lime

Which foolish birds are caught with. Can, I ask,

This face of rural beauty be a mask

For discontent, and poverty, and crime;

These spreading towns a cloak for lawless will?

Forbid it, Heaven! and Merry England still

Shall be thy rightful name, in prose and rhyme!Merry England is an easily mocked concept in today’s society, but in my view it carries a perennial insight: that the decadence and excess of the city is of a piece with puritanical restraint. Both apparently opposite features reflect an urban sophistication and the ruling imperative of commerce. The moneymaking frenzy of cities like London gave rise to excessive consumption and the relaxing of prior moral and social norms. Yet the 17th century Puritans were in large part cityfolk, alienated from rural tradition and well represented amongst bankers, merchants and urban middle class trades and professions.

William Hogarth’s most famous engraving is Gin Lane, which shows a street filled with people immiserated by the gin craze, a child toppling out of its mother’s arms, emaciated figures dying in the open, madmen dancing with corpses, a pawn-shop with the grandeur of a bank eagerly sucking in objects of domestic industry and converting them into gin money. Less well known is the image that accompanied it, the engraving Beer Street. In this latter engraving, plump and prosperous individuals pause from their labour to receive huge foaming mugs of ale, buxom housemaids flirt with cheerful tipplers, bright inn signs are painted, buildings are going up, and the pawn-shop is going out of business.

Merry England is an image of a society centred on human life and happiness rather than the demands of commerce. Here labour and rest both have their place: noble objects like a fine building and a bounteous meal are provided by hard work, but once completed, time is devoted to appreciating and relishing the finished product. Decoration and adornment are the outward sign of this; they are by their nature a form of abundance. The finite object of labour and production thus gives rise to an infinite realm of feast, celebration, adornment and signification. This enchanted public sphere, shaped to the human person, is limitless within its limits, and points beyond itself to the truly limitless and eternal world of the transcendent.

In the commercially determined sphere of modernity, it is instead work and consumption that are rendered limitless. The objects have become entirely ones of consumption — there is no limit to the consumption of gin, which stands in for all consumer objects. Hogarth shows us the humane objects of household industry — the good cooking pots, the tongs, the saw and the kettle — replaced with money. Liquidity is everywhere, capital has broken down the social order, removing all distinctions of sex, age and class. Now all persons and all things are joined together by a single seamless system of predation.

The alternative that many advocated to this situation was embodied in the Temperance movement: a Puritan-dominated enterprise which saw drinking as a threat to industry as well as the spiritual and moral health of the nation. This is a deep tendency in the British character: the impulse to look upon poverty and distress as a culpable disease and to preach individual self-restraint as the cure. Puritans were often well-to-do, literate townspeople, whose collective refusal to participate in dancing, drama, drinking, gambling, racing and boxing not only set them apart from the boisterous lower orders, but also from the quaffing, hunting, hawking and whoring nobility.

A 4000 Year Old Recipe for the Babylonian New Year

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 29 Dec 2020Help Support the Channel with Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/tastinghistory

Tasting History Merchandise: crowdmade.com/collections/tastinghistoryFor further reading on these recipes visit: https://www.academia.edu/40639453/Foo…

Follow Tasting History here:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tastinghist…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TastingHistory1

Reddit: r/TastingHistory

Discord: https://discord.gg/d7nbEpyTasting History’s Amazon Wish List: https://www.amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls…

LINKS TO INGREDIENTS & EQUIPMENT**

Canon EOS M50 Camera: https://amzn.to/3amjvwu

Canon EF 50mm Lens: https://amzn.to/3iCrkB8

Le Creuset Dutch Oven 7.25 qt: https://amzn.to/3mLkWJFLINKS TO SOURCES**

https://www.academia.edu/40639453/Foo…

Gojko Barjamovic: https://nelc.fas.harvard.edu/people/g…

Myths from Mesopotamia translated by Stephanie Dalley: https://amzn.to/2Kvzr7b

Babylon by Paul Kriwaczek: https://amzn.to/37GJRJT

The Oldest Cuisine in the World by Jean Bottéro: https://amzn.to/2Jf1eIm

The Babylonian Akitu Festival by Svend Aage Pallis: https://amzn.to/2M5hZa7

The Babylonian New Year Festival by Karel Van Der Toorn: https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/97…**Amazon offers a small commission on products sold through their affiliate links, so each purchase made from this link, whether this product or another, will help to support this channel with no additional cost to you.

Editor: WarwicSN – https://www.youtube.com/WarwicSN

Subtitles: Jose MendozaDISH NAME

ORIGINAL c.1740BC RECIPE (From The Yale Babylonian Tablets)

Tuh’u sirum saqum izzaz me tukan lipia tanaddi tusammat tabatum sikara susikillum egegerum kisibirrum smidu kamunum alutum tukammas-ma karsum hazannum teterri kisibirrum ina muhhi sipki tusappah suhutinnu kisibirrum isarutu tanaddi.Tuh’u. Lamb leg meat is used. Prepare water. Add fat. Sear. Add in salt, beer, onion, arugula, cilantro, samidu, cumin, and beets. Put the ingredients in the cooking vessel and add crushed leek and garlic. Sprinkle the cooked mixture with coriander on top. Add suhutinnu and fresh cilantro.

MODERN RECIPE

INGREDIENTS

– 1lb (450g) Leg of Lamb Chopped into bite size pieces.

– 3-4 Tablespoon Oil or Rendered Fat

– 1 ½ teaspoons Salt

– 2 Cups (475ml) Water

– 12 oz (350ml) Beer – (A sour beer and German Weissbier are recommended, but any non-hoppy beer will suffice)

– 1 Large Onion Chopped

– 2 Cups Arugula Chopped

– 3/4 Cup Cilantro Chopped

– 2 Teaspoons Cumin Seeds crushed

– 2 Large Beets (approx. 4 cups) Chopped

– 1 Large Leek Minced

– 3 cloves Garlic,

– 1 Tablespoon Dry Coriander Seeds

– Additional Chopped Cilantro for garnish

– Samidu* (Something akin to 1 Persian Shallot)

– Suhutinnu* (Something akin to Egyptian Leek for garnish)

*These ingredients have no definite translation; the shallot and leek are the best guesses of scholars at Yale and Harvard Universities)METHOD

1. Add the oil/fat to a large pot and set over high heat. Sear the lamb for several minutes in the oil until lightly browned.

2. Add the onions and let cook for 5 minutes, then add the beets and let cook for 5 minutes. Then add the salt, beer, arugula, cilantro, samidu (shallot) and cumin and bring to a boil. Mash the garlic into a paste and mix with the leek, then add to the pot.

3. Lower heat to medium and let simmer for approximately 1 hour, or until the beets and meat are cooked to your liking.

4. Once cooked, dish it into a bowl and sprinkle with coriander seeds. Garnish with fresh cilantro and suhutinnu (leek)PHOTO CREDITS

Crocus: By Safa.daneshvar – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, http://bit.ly/3hfNN7F

Statue of Nabu: By Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, http://bit.ly/2KodVkV

Temple of Nabu at Borsippa: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia Commons

Ishtar Gate: Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia Commons

King Marduk-zakir-shumi: By Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)Throne Dais of Shalmaneser III at the Iraq Museum.jpg, CC BY 4.0, http://bit.ly/3nMw22j#tastinghistory #babylon #akitu

QotD: Heinlein’s “Crazy Years”, Alfred Korzybski’s General Semantics, and modern times

While Heinlein (as far as I know) supplied no rationale for the advent and the recession of the craziness in the Crazy Years, A.E. van Vogt was freer with his speculations: insanity, either of individuals or of peoples, in van Vogt’s stories (and perhaps in the theories of Alfred Korzybski, who discovered or invented General Semantics) is caused by a fracture or disjunction between symbol and object. When your thoughts, and the thing about which you think, do not match up on a cognitive level, that is a falsehood, a false belief. When the emotions associated with the thought do not match to the thing about which you think, that is a false-to-facts association, which can range from merely a mistake to neurosis to psychosis, depending on the severity of the disjunction. You are crazy. If you hate your sister because she reminds you of your mother who beat you, that association is false-to-facts, neurotic. If you hate your sister because you have hallucinated that you are Cinderella, that association is falser-to-facts, more removed from reality, possibly psychotic.

The great and dire events of the early Twentieth Century no doubt confirmed Korzybski in the rightness of this theory. Nothing prevents a race of people from contracting and fomenting a false-to-facts belief: the fantasies of the Nazi Germans, pseudo-biology and pseudo-economics combined with the romance of neo-paganism, stirred the psyche of the German people for quite understandable reasons. From the point of view of General Semantics, the Germans had divorced their symbols from reality, they mistook metaphors for truth, and their emotions adapted to and reinforced the prevailing narrative. They told themselves stories about Wotan and the Blood, about being betrayed during the Great War, about needing room to live, about the wickedness of Jewish bankers and shopkeepers, about the origin of the wealth of nations — and they went crazy.

The Russians, earlier, and for equally psychological and psychopathic reasons told themselves a more coherent but more unreal story about history and destiny, taken from a Millenarian cultist named Marx, and they were, on an emotional level even if not on a cognitive level, convinced that shedding the blood of millions would bring about wealth as if from nowhere. And, because they used the word “scientific” to describe their brand of socialism, they actually thought their play-pretend neurotic story was a scientific theory that had been discovered by rigorous ratiocination — and they went crazy.

Berlin was bombed into submission during the Second World War, and the Berlin Wall collapsed along with the Soviet Empire at the end of the Cold War. But the modern methods of erecting false-to-facts dramas appealing to mass psychology, once discovered, did not fall when their practitioners fell: scientific socialism, naziism, fascism, communism, all have in common the subordination of word-association to political will. All these doctrines have a common ancestor, which is the social engineering theory of language: if you change the connotation of word, so the theory runs, you change the connotations of thoughts. General Semantics says that if an individual, or whole people en mass, adopt deliberately false beliefs, supported by deliberately manipulative word-uses, he or they will have increasingly unrealistic and maladaptive behaviors. Introduce Political Correctness, ignore factual correctness, and the people will go crazy.

The main sign of when madness has possessed a crowd, or a civilization, is when the people are fearful of imaginary or trivial dangers but nonchalant about real and deep dangers. When that happens, there is gradual deterioration of mores, orientation, and social institutions — the Crazy Years have arrived.

John C. Wright, “The Crazy Years and their Empty Moral Vocabulary”, John C. Wright, 2019-02-18.