Forgotten Weapons

Published Feb 13, 2015Manufactured in Brooklyn from 1861 until 1863, Moore’s revolver was a 7-shot single-action piece firing .32 rimfire cartridges. What makes it unique is its swing-out cylinder design — the first commercial revolver in the US to use this mechanism. A latch on the back of the frame released the entire barrel and cylinder assembly, allowing it to tip over to the right, exposing the chambers for loading and unloading. The ejector rod is stored under the barrel, but must be removed and used by hand when needed. Moore’s revolvers were popular with New Yorkers heading off to the Civil War and almost 8000 were made, but production was halted when Rollin White successfully sued for patent infringement (over his patent on the bored-though cylinder).

http://www.forgottenweapons.com

Theme music by Dylan Benson – http://dbproductioncompany.webs.com

March 18, 2024

Moore’s Patent Revolver (Swing-Out Cylinder)

September 7, 2023

QotD: Techno-pessimism

Unfortunately, by any objective measure, most new things are bad. People are positively brimming with awful ideas. Ninety percent of startups and 70 percent of small businesses fail. Just 56 percent of patent applications are granted, and over 90 percent of those patents never make any money. Each year, 30,000 new consumer products are brought to market, and 95 percent of them fail. Those innovations that do succeed tend to be the result of an iterative process of trial-and-error involving scores of bad ideas that lead to a single good one, which finally triumphs. Even evolution itself follows this pattern: the vast majority of genetic mutations confer no advantage or are actively harmful. Skepticism towards new ideas turns out to be remarkably well-warranted.

The need for skepticism towards change is just as great when the innovation is social or political. For generations, many progressives embraced Marxism and thought its triumph inevitable. Future generations would view us as foolish for resisting it — just like Thoreau and the telegraph. But it turned out that Marxism was a terrible idea, and resisting it an excellent one. It had that in common with virtually every other utopian ideal in the history of social thought. Humans struggle to identify where precisely the arc of history is pointing.

Nicholas Phillips, “The Fallacy of Techno-Optimism”, Quillette, 2019-06-06.

May 28, 2023

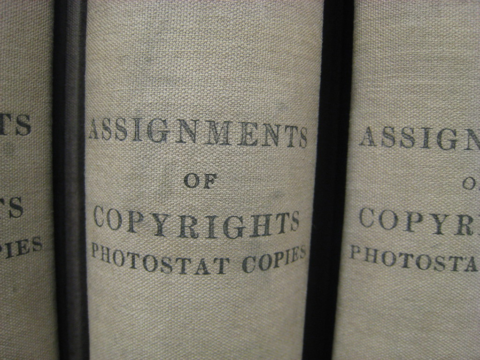

Musical copyrights – crazy as they are now – were far worse in history

Ted Gioia outlines just how the concept of musical copyrights produced even more distortions in the past than they do today:

People tell me it was never this bad before. But they’re wrong. The music copyright situation was even crazier 500 years ago.

The Italians took the lead in this, and it all started with Ottaviano Petrucci gaining a patent from the Venetian Senate for publishing polyphonic music with a printing press back in 1498. Andrea Antico secured a similar privilege from Pope Leo X, which covered the Papal States.

It’s hard to imagine a Pope making decisions on music IP, but that was how the game was played back then. In 1516, Pope Leo actually took away Petrucci’s monopoly on organ music, and gave it to Antico instead. You had to please the pontiff to publish pieces for the pipes.

Over time, this practice spread elsewhere. In a famous case, the composer Lully was granted total control over all operas performed in France. He died a very wealthy man — with five houses in Paris and two in the country. His estate was valued at 800,000 livres—some 500 times the salary of a typical court musician.

But the most extreme case of music copyright comes from Elizabethan England. Here the Queen gave William Byrd and Thomas Tallis a patent covering all music publishing for a period of 21 years. Not only did the two composers secure a monopoly over English music, but they also could prevent retailers or other entrepreneurs in the country from selling “songs made and printed in any foreign country.”

If anybody violated this patent, the fine was 40 shillings. And the music itself was seized and given to Tallis and Byrd. They probably had quite a nice private library of scores by the time the patent expired.

But that’s not all. Byrd and Tallis’s stranglehold on music was so extreme it even covered the printing of blank music paper. That meant that other composers had to pay Tallis and Byrd even before they had written down a single note. Not even the Marvin Gaye estate makes those kinds of demands.

Tallis died a decade after the patent was granted—putting Byrd in sole charge of English music. I’d like to tell you that he exercised his monopoly with a fair and open mind—especially because I so greatly esteem Byrd’s music, and also I’d like to think that composers are better at arts management than profit-driven businesses. But the flourishing of music publishing in England after the expiration of the patent — when, for a brief spell, anybody could issue scores — makes clear that Byrd did more to constrain than empower other composers.

April 4, 2023

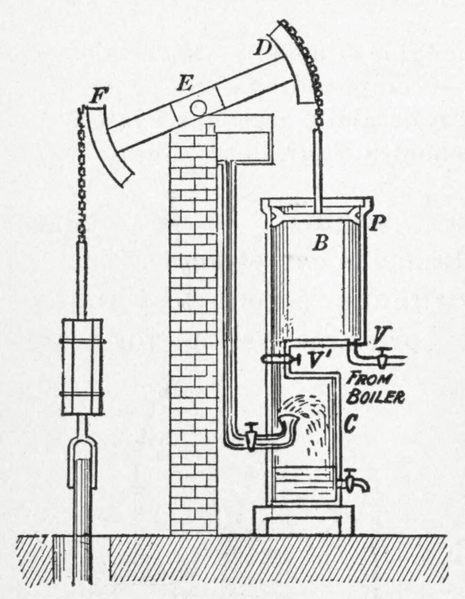

When the steam engine itself was an “intangible”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the steam engine patent of James Watt didn’t immediately lead to Watt and his partner Matthew Boulton building a factory to create physical engines:

Diagram of a Watt steam engine from Practical physics for secondary schools (1913).

Wikimedia Commons.

… one of the most famous business partnerships of the British Industrial Revolution — that between Matthew Boulton and James Watt from 1775 — was originally almost entirely based on intangibles.

That probably sounds surprising. James Watt — a Scottish scientific instrument-maker, chemist and civil engineer — became most famous for his improvements to the steam engine, an almost archetypal example of physical capital. In the late 1760s he radically improved the fuel efficiency of the older Newcomen engine, and then developed ways to regulate the motions of its piston — traditionally applied only to pumping water — so that it could be suitable for directly driving machinery (I’ll write more on the invention itself soon). His partnership with Matthew Boulton, a Birmingham manufacturer of buttons, candlesticks, metal buckles and the like — then called “toys” — was also based from a large, physical site full of specialised machinery: the Soho Manufactory. On the face of it, these machines and factories all sound very traditionally tangible.

But the Soho Manufactory was largely devoted to Boulton’s other, older, and ongoing businesses, and it was only much later — over twenty years after Boulton and Watt formally became partners — that they established the Soho Foundry to manufacture the improved engines themselves. The establishment of the Soho Foundry heralded James Watt’s effective retirement, with the management of this more tangible concern largely passing to his and Boulton’s sons. And when Watt retired formally, in 1800, this coincided with the full depreciation of the intangible asset upon which he and Boulton had built their business: his patent.

Watt had first patented his improvements to the steam engine in 1769, giving him a 14-year window in which to exploit them without any legal competition. But his financial backer, John Roebuck, who had a two-thirds share in the patent, was bankrupted by his other business interests and struggled to support the engine’s development. Watt thus spent the first few years of his patent monopoly as a consultant on various civil engineering projects — canals, docks, harbours, and town water supplies — in order to make ends meet. The situation gave him little time, capital, or opportunity to exploit his steam engine patent until Roebuck was eventually persuaded to sell his two-thirds share to Matthew Boulton. With just eight years left on the patent, and having already wasted six, Boulton and Watt lobbied Parliament to grant them an extension that would allow them to bring their improvements into full use. In 1775 Watt’s patent was extended by Parliament for a further twenty-five years, to last until 1800. It was upon this unusually extended patent that they then built their unusually and explicitly intangible business.

How was it intangible? As Boulton and Watt put it themselves, “we only sell the licence for erecting our engines, and the purchaser of such licence erects his engine at his own expence”. This was their standard response to potential customers asking how much they would charge for an engine with a piston cylinder of particular dimensions. The answer was, essentially, that they didn’t actually sell physical steam engines at all, so there was no way of estimating a comparable figure. Instead, they sold licences to the improvements on a case-by-case basis — “we make an agreement for each engine distinctly” — by first working out how much fuel a standard, old-style Newcomen engine would require when put to use in that place and context, and then charging only a third of the saving in fuel that Watt’s improvements would provide. “The sum therefore to be paid during the working of any engine is not to be determined by the diameter of the cylinder, but by the quantity of coals saved and by the price of coals at the place where the engine is erected.” They fitted the licensed engines with meters to see how many times they had been used, sending agents to read the meters and collect their royalties every month or year, depending on the location.

This method of charging worked well for refitting existing Newcomen engines with Watt’s improvements — in those cases the savings would be obvious. It also meant that Boulton and Watt incentivised themselves to expand the total market for steam engines. The older Newcomen engines were mainly used for pumping water out of coal mines, where the coal to run them was at its cheapest. It was one of the few places where Newcomen engines were cost-effective. But for Watt and Boulton it was at the places where coals were most expensive, and where their improvements could thus make the largest fuel savings, that they could charge the highest royalties. As Boulton wrote to Watt in 1776, the licensing of an engine for the coal mine of one Sir Archibald Hope “will not be worth your attention as his coals are so very cheap”. It was instead at the copper and tin mines of Cornwall, where coal was often expensive, having to be transported from Wales, that the royalties would be the most profitable. As Watt put it to an old mentor of his in 1778, “our affairs in other parts of England go on very well but no part can or will pay us so well as Cornwall”.

February 20, 2023

Thirteen reasons the Dutch did better financially than the English in the Seventeenth Century

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes investigates the huge differences between the rival English and Dutch financial markets in the 17th century:

The courtyard of the exchange in Amsterdam (De binnenplaats van de beurs te Amsterdam), 1653.

Oil painting by Emanuel de Witte (1617-1692) from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen collection via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the weird things about Britain, despite its being the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, is that its financial infrastructure was for a long time remarkably backward. Its “Financial Revolution”, by which both people and the state began to borrow at ever lower interest rates, only really took off in the early eighteenth century — long after London’s extraordinary growth in 1550-1650, when it had suddenly expanded eightfold to become one of Europe’s most important commercial hubs. Indeed, even for much of the late seventeenth century, England lacked many of the most basic financial institutions that had been used for decades and decades by their most important rival and trading partner, the Dutch Republic.

I was especially intrigued when I stumbled across a discussion of Dutch policies and customs, written up in around 1665 by the young merchant Josiah Child, and published a few years later: a kind of wishlist of many of the things that made the Dutch so wealthy, and which the English continually failed to emulate:

- The Dutch councils of state and war always included merchants who had experience of trading and living abroad — Child was perhaps just angling for some influence here, but for all that merchants were getting more influential, in England they were not actually in charge.

- Gavel-kind succession laws, whereby all children got an equal share of their parents’ estates, rather than it all going to the eldest. English primogeniture, by contrast, apparently left a lot of gentlemen’s younger sons having to become apprenticed to merchants.

- High regulatory standards for goods. A barrel of Dutch-packed herring or cod would apparently be accepted by buyers just by viewing the marks, without having to open them up to check. English-packed goods, by contrast, were rarely trusted because the fish would turn out to be rotten or even missing — the English regulators’ stamps of approval were reputedly given to anyone who would pay.

- Encouragement for inventors of new products, techniques, and import trades, who received rewards from the state, and not just temporary monopoly patents.

- Ships, called fluyt, which were cheaper to build, required fewer sailors, and were easier to handle. Despite being only very lightly armed, they sailed in fleets for protection, when necessary being convoyed by ships of war. English trading ships, by contrast, were each heavily armed, but with those cannon taking up room and weight that could have been used for carrying merchandise.

- Education of all children, even girls, in arithmetic and keeping accounts. As Child put it, this infused in the Dutch “a strong aptitude, love, and delight” for commerce. It also meant that husbands and wives were real partners in many businesses — something that impressed almost all foreign visitors to the Netherlands.

- Low customs duties, but high consumption taxes. Very low customs duties, on both imports and exports, meant that it was often very profitable to trade with the Netherlands. The Dutch were famed for their many ships, and for their granaries bursting with grain, despite growing hardly any trees or crops themselves. To fund their state, they instead overwhelmingly relied on the gemene middelen — taxes on the sale of wine, beer, meat, fuel, candles, salt, soap, flour, cloth, and a host of other goods, with many of the higher rates reserved for expensive luxuries. Much like modern value-added taxes, these taxes on consumption raised revenue while preserving the all-important incentive to save and invest.

- Thrifty living — which, come to think of it, was probably related to the high consumption taxes, although Childs doesn’t seem to have noticed the connection. Dutch thrift was thought by the English to be especially useful because it allowed wage costs to be kept low — essential for maintaining competitiveness in international markets — while preventing the country having a trade deficit. The English always worried they were sending too much of their silver abroad to pay for French wines and other luxuries, but the Dutch appeared to have prevented this without resorting to import tariffs that might annoy trading partners and prompt retaliation.

- Religious toleration, which attracted all sorts of industrious immigrants to bring their families and wealth. (Incidentally, as I’ve mentioned before, this was also one of the key attractions of Livorno, set up by the Medici Dukes of Tuscany to be a major trading hub.)

- The use of the Law-Merchant, which meant that all controversies between merchants and tradesmen were decided in just 3 or 4 days’ time. England, rather strangely for such an increasingly commercial nation, did not develop merchant courts with a specific jurisdiction or a distinct body of merchant law — disputes instead had to be resolved in the royal common-law or equity courts, in the Admiralty court, or else abroad. The English courts, however, were often slow. Child complained that cases often took half a year, and often much longer. (Incidentally, slow and rotten justice in the Court of Chancery, the key equity court used by merchants in England, was one of the reasons Francis Bacon was impeached by Parliament and sacked as Lord Chancellor.)

- Transferrable bills of exchange — in other words, the circulation of credit notes as a currency. These were not properly supported by English laws, but allowed Dutch merchants to trade a lot more frequently. English merchants often had to wait some six months to a year before receiving all the coin from selling their foreign goods in London, so as to purchase goods again to make fresh trades. They spent much of their time chasing shopkeepers for payment. But the Dutch, by being able to easily buy and sell their credit notes, could “turn their stocks twice or thrice in trade”, immediately settling their accounts and making fresh purchases. (I intend to look into this in a lot more detail soon, as finding a way to bills of exchange transferrable in England appears to have been a major project for many of the mid-seventeenth-century inventors and improvers — after just a cursory glance, transferability was only secured in law as late as 1704.)

- Banks. Or rather, as Child actually put it, “BANKS”. In England many of the functions of banks gradually evolved from the practices of individual goldsmiths and the scriveners — legal clerks who specialised in property transfers and mortgages. There was certainly nothing so secure as the municipal Wisselbank of Amsterdam, established in 1609, which had various monopoly powers as a clearing-house for bills of exchange and was backed by a vault full of bullion. Nor the municipal Bank van Lening, established in 1614, which was a pawnbroker modelled on the Italian Monte di Pietà, or mounts of piety, designed to make small and low-cost loans to the poor.

- “PUBLIC REGISTERS” — again capitalised by Child — of all lands and houses sold or mortgaged. This item on the policy wishlist would not be ticked off for England until two centuries later, but the key advantage was to prevent lawsuits over land titles — still cited as a major problem even in the 1690s — and so make land more genuinely secure for mortgages.

Finally, the result of many of these policies was the Dutch had significantly lower interest rates — often just 3-4% when the English were still lending and borrowing at 6-8%. Indeed, this list was made because of a long-standing English policy debate I’ve been researching, on whether to lower the legal maximum rate of interest.

Garate Anitua y Cia “El Tigre” – Winchester 1892 Copy

Forgotten Weapons

Published 5 Jun 2016Spain was historically a major center of patent infringement in firearms manufacture because its patent law left open a big loophole: patents were only enforceable if the patent holder actually manufactured their guns in Spain. The major European and American firearms manufacturers were not interested in setting up plants in Spain, and so their patents were not enforced there, leaving Spanish shops and factories legally free to copy them.

One of the more successful copies was the “El Tigre“, a clone of the Winchester 1892 lever action rifle made by Garate Anitua y Cia. Ironically, Garate actually registered their own patent on the design since Winchester hadn’t bothered to, and that patent was enforced, since Garate did make the guns in Spain. Their copy was chambered for the .44-40 Winchester cartridge, known in Spain as the .44 Largo. This made it compatible with many of the revolvers in the country of American, Spanish, and Belgian origin, and thus quite popular with a wide variety of groups. Rural citizen militias and the Guardia Civil both used significant numbers of El Tigre carbines. They were also fairly popular in the United States, as the cost was substantially lower than a true Winchester. Many Hollywood films and shows used them as less expensive prop guns, especially for scenes where guns would be handled roughly.

Despite their competitive cost, the El Tigres were actually quite good guns, and served their owners well.

December 9, 2022

Rod Bayonet Springfield 1903 (w/ Royalties and Heat Treat)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 20 Nov 2016(Note: I misspoke regarding Roosevelt’s letter; he was President at the time and writing to the Secretary of War)

The US military adopted the Model 1903 Springfield rifle in 1903, replacing the short-lived Krag-Jorgenson rifle. However, the 1903 would undergo some pretty substantial changes in 1905 and 1906 before becoming the rifle we recognize today. The piece in today’s video is an original Springfield produced in 1904, before any of these changes took place.

The most notable difference is the use of the rod bayonet. When the 1903 was in development, the Ordnance Department opined that the bayonet was largely obsolete, and that it was unnecessary to encumber soldiers with a long blade hanging from the belt. Instead, the new rifle would have a retractable spike bayonet that could double as cleaning rod and would be stored in the rifle stock, unobtrusive to the soldier. This ended in 1905 with a critical letter from Theodore Roosevelt (who was Secretary of War at the time). As the rod bayonet was replaced with a traditional blade bayonet, the cartridge would also be improved to a new style spitzer projectile at higher velocity, and the rifles’ stocks, hand guards, and sights were redesigned.

In this video I also discuss two often misunderstood elements of the Springfield’s history: heat treating and patent royalties. Are low serial number 1903 Springfields safe to shoot, and why or why not? And did the US government actually pay royalties to Germany for copying Mauser elements in the 1903?

(more…)

April 18, 2022

7.62mm Rifle L8: The Last Gasp of the Service Lee Enfield

Forgotten Weapons

Published 13 Dec 2021http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.forgottenweapons.com

After the British adopted the FAL as the L1A1 rifle, there was still an interest in converting stocks of existing No4 Enfield rifles to the new 7.62x51mm cartridge for reserve and training use. A conversion system was developed using a new barrel, bolt, and magazine — although the Sterling company was doing much the same thing at the same time and intellectual property lawsuits would close the project for nearly 10 years. By the time the lawsuits cleared up, it had become clear that the rifles were neither particularly successful nor particularly necessary anymore. The problem the British has was one of accuracy — the 7.62mm version just wasn’t sufficiently accurate. A thousand were sold to Sierra Leone, and a few more used in New Zealand and by cadet organizations in the UK, but the project was basically a failure.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle 36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

April 3, 2022

King James I and the problem of gold and silver thread in England

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes began to research what appeared to be a minor economic issue that very quickly took over his time going deep down the gold and silver market rabbit hole:

A hammered silver sixpence of James I dated 1603 from the first coinage with a thistle mintmark. Obverse features a right facing crowned bust with the numerals VI behind and the inscription JACOBVS*DG*ANG*SCO*FRA*ET*HIB*REX. The reverse has a shield with the royal arms and the date 1603 above. The reverse inscription is EXERGAT* DEVS*DISSIPENTVR*INIMICI.

FindID 510696 – https://finds.org.uk via Wikimedia Commons

When England’s Parliament met in 1621, it was mainly supposed to vote King James I the funds to fight a war. His daughter’s domain, the Palatinate of the Rhine, had just been invaded, and the European Protestant cause was under grave threat. As I set out two weeks ago, however, the House of Commons had seized the chance to pursue a scandal. Jealous of the Crown’s challenge to their status as local power-brokers, and hoping to embarrass the king’s favourite, the Marquess of Buckingham, MPs opened an investigation into Sir Giles Mompesson’s patent to license inns.

When it came to inns, I argued that the case against Mompesson was flimsy (making me perhaps the only person to have defended him for over four hundred years). He appears to have been a trusted and able bureaucrat, the source of his downfall being his sheer effectiveness. But the flimsiness of the case against him was not enough to stop the political witch-hunt. Next on the list was a project he had administered for making gold and silver thread.

It sounds obscure, and I was fully expecting to write up a short overview of a niche industry that just happened to be thrust into the limelight of 1620s politics. That was a month ago, when I first started drafting this piece. But pulling on the golden thread revealed a desperate, decade-long battle between the City and the Crown, over who would get to control the financial stability of the realm. I’m sorry for the delay in publishing it, but I hope I’ve made it worth the wait.

January 8, 2022

The Board of Green Cloth — the original “we investigated ourselves and found us innocent” organization

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains how England managed to avoid the first attempt by King James I to impose absolute monarchy — that is, putting the Stuart notions of the “divine right of kings” in place of royal powers limited by the Parliamentary control of the royal income:

King James I (of England) and VI (of Scotland)

Portrait by Daniel Myrtens, 1621 from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

The year 1610 might by the most under-rated year in British history. It was the year in which England almost became a more permanent absolutist monarchy. Had things gone only a little differently, King James I might have obtained a substantial annual income — enough to pay off his debts within just a few years, to run a substantial surplus, and perhaps even to never have to summon a Parliament ever again. Over the course of a few decades, so long as they didn’t require too many extraordinary taxes to pay for one-off wars, the Stuart kings could have ruled without challenge, issuing proclamations that would have gradually taken on the force of laws.

[…]

As we saw in the last instalment of this series, James I’s finances were desperate. His predecessor had left him substantial war debts, and he was running a large deficit, so the chances of repaying them anytime soon were slim. So in 1604 he had summoned a Parliament with the aim of making a financial deal. Parliaments were typically called in order for the monarch to raise one-off, extraordinary taxes, usually in times of rebellion or war. Rather confusingly from today’s perspective, these taxes were known as “subsidies”, because they were a subsidy to the Crown. Yet James and his ministers wanted Parliament to instead establish peacetime taxes that would be both ongoing and ordinary — what came to be known as “support”. The deal was that he would give up some of his least popular feudal prerogative rights in return.

The House of Commons did not go for the deal in 1604, as we saw. They may have hated feudal obligations like purveyance or wardship — the requisitioning of goods for the court, and the Crown’s control of noble heirs whose fathers had died before they came of age — but they also saw some major risks in trying to make a deal with the king.

When it came to the matter of purveyance, for example, many members of Parliament wanted to stamp out the abuses rather than see the institution abolished. They thought it perfectly legal for the Crown to compulsorily purchase goods, and even to requisition the carts to carry them. What they complained of was that many purveyors were failing to give compensation immediately, and that corrupt purveyors were sometimes taking more than was required, pocketing the difference for themselves. Many MPs also argued that there was no legal basis for purveyors to determine their own prices for the provisions that they seized — a privilege that the Crown adamantly insisted upon.

James’s predecessor Queen Elizabeth I had granted a concession over patent disputes — “patents” at that time were a rather different and much wider legal notion than our more product-oriented modern patents: the monarch granted patents to assign lands and titles, appoint officials, create cities or guilds, or to allow monopoly privileges over an economic resource among other purposes. The concession was that patent disputes would be litigated in common-law courts rather than by royally appointed judges.

Yet by extending the jurisdiction of the common-law courts to monopolies, Elizabeth opened the floodgates of complaints against all prerogative courts — especially against the court of royal household officials responsible for commissioning the purveyors, known as the Board of Green Cloth.

To Hyde and his followers, this court was especially corrupt. Whereas the trying of monopoly patents had at least been done in the more general prerogative courts, anyone hauled before the Green Cloth for denying the purveyors was effectively being tried, judged, fined, and even imprisoned, by the very organisation that was accusing them. Even if purveyors really were acting illegally by naming their own prices, as opponents maintained, there would be no justice so long as the purveyors effectively judged themselves. For Hyde and his allies then, they wished to do to purveyance what they had done to monopolies — to subject them to the common law.

December 27, 2021

Great Celebrity Breakups: Winchester and John Browning

Forgotten Weapons

Published 26 Aug 2021http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.forgottenweapons.com

In August 1903, Thomas Bennett (head of the Winchester company) wrote a letter to his many distributors and agents explaining how Winchester had decided to part ways with the Browning Brothers, and how the company would certainly be better off as a result. The gun at the heart of the breakup was Browning’s new self-loading shotgun, the Auto-5. Browning would end up taking the design to FN, where it became a massive commercial success — but the whole story is really much more nuanced than most people recognize.

This isn’t simply a matter of Browning demanding a royalty arrangement, but rather much more …

Nathan Gorenstein’s biography of John Browning is available on Amazon: https://amzn.to/37Sx9XS

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle 36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

December 4, 2021

When King James VI became King James I and VI

In his latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes discusses how the King of Scotland succeeded to the English throne as well:

King James I (of England) and VI (of Scotland)

Portrait by Daniel Myrtens, 1621 from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s late March 1603, and an exhausted messenger arrives in Edinburgh bearing a sapphire ring. He has ridden for over two days straight, over hundreds of miles, and his hair and clothes are matted with blood — on the way he had fallen from his horse, a hoof striking him directly in the head. It’s a miracle he’s alive, but he knows it has been worth it. He is the very first to tell you that your childless first cousin twice removed — the killer of your mother, whom you never knew — is finally dead. You, King James VI of Scotland, are James I of England as well.

[…]

James’s accession was a frenzy. From the very moment of Elizabeth’s death, her entire patronage network was turned on its head. Her chief ministers, the Privy Council, were relatively safe. Some of them had been corresponding with James for years. But they could only look on, anxiously, as a rush of would-be cronies went north to meet their new king. The exhausted messenger with the sapphire ring, Sir Robert Carey, was just the first. Carey had been related to Elizabeth I on her mother’s side — he was her first cousin once removed. (Carey’s grandmother was the “other Boleyn girl”, played by Scarlett Johansson in the 2008 film — although there’s no solid evidence, it’s not totally impossible that Carey was actually related to Elizabeth on her father’s side instead …) But that family connection meant nothing now that the queen was dead.

The sudden reset of the source of all patronage meant that the earlier the access to the new king’s person, the greater the chance of gaining his favour. Carey may have angered the Privy Council by riding ahead of their formal letters to James, but his exertion won him an on-the-spot appointment as a gentleman of the bedchamber, and his wife became a lady in waiting to James’s queen. The Careys were soon charged with the care of the royal couple’s younger sickly child, and when that child eventually became Charles I, Carey was made Earl of Monmouth. Not a bad result for a head wound and a two days’ ride, though I’m sure the horses would disagree. An old proverb about England was that it was “a paradise for women, a purgatory for servants, and a hell for horses” — something that James’s accession really put to the test. One teenage noblewoman reported how she and her mother killed three horses in a single day, pushing them hard despite the heat, in their rush to meet the new queen.

Just as courtiers flocked to James, however, the king wanted to win friends and allies too. So he handed out favours like confetti. Before he had even reigned a single year, he had created 934 knighthoods — already more than the 878 that Elizabeth I, her generals, and her lord deputies in Ireland had created over the course of her entire 45-year reign. One morning, during his journey down to London, James knighted more people than Elizabeth had in her first five years — all before he’d even had his breakfast. The sheer volume of new knighthoods prompted Francis Bacon — one of about 300 to be knighted in London ahead of the coronation — to call it a “divulged and almost prostitute title”.

The same went for peerages. Elizabeth, over her long reign of almost half a century, had created only 18 new titles. James, before he had even been crowned, had already created 12 — mostly turning knights into lords, and raising some lords into earls. Along with the honours came grants of land, annual pensions, and one-off gifts — not only to James’s new English courtiers, but to his old Scottish favourites too. James’s arrival was an explosion of largesse. (Not all were happy about the relative loss of favour, of course […] at least one pro-invention courtier got involved in a treasonous plot against the new king and ended up losing his head.)

James’s largesse even extended to policy. As he triumphantly marched into London, he issued a proclamation to immediately suspend all of Elizabeth’s patent monopolies, to be re-granted pending review. (This did not apply to patents for trading corporations or guilds.) Rather than leaving the validity of patents to be tested in the common-law courts, at great legal cost to those affected, he would have his Privy Council systematically examine them first, only allowing them if they were in the public interest. He characterised it as a continuation — even a “perfecting” — of Elizabeth’s partial measures a couple of years earlier, which we discussed in Part II. With his proclamation also condemning various other unpopular things, like high court fees, his new subjects were overjoyed.

But the honeymoon was not to last.

October 23, 2021

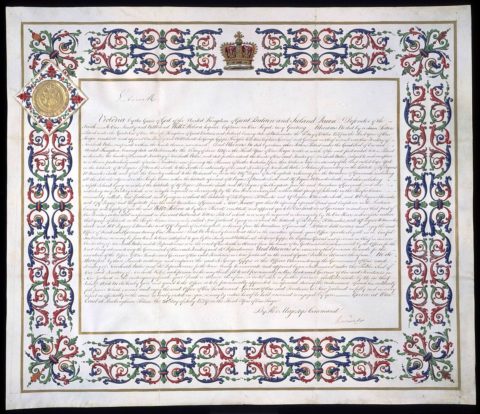

The English Statute of Monopolies gets far more credit than it actually deserves

The Statute of Monopolies (1624) is often said to have been critical in helping to start England on the road to the Industrial Revolution, but in the latest Age of Invention newsletter Anton Howes argues it is far more complicated than it seems:

Letters Patent Issued by Queen Victoria, 1839. On 15 June 1839 Captain William Hobson was officially appointed by Queen Victoria to be Lieutenant Governor General of New Zealand. Hobson (1792 – 1842) was thus the first Governor of New Zealand.

Constitutional Records group of Archives NZ via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most frequently mentioned landmarks in the history of intellectual property is the Statute of Monopolies, passed by the English parliament in 1624. I’ve often seen it lauded as the beginning of the system of patents for invention, or the first patent law. I remember giving a talk a few years ago where I downplayed the role of formal institutions in encouraging the Industrial Revolution, prompting an outraged economist in the audience to point to the law as a sort of gotcha — “here’s a better explanation: with patents you incentivise invention, and the Brits had just invented patents”.

Which is all to illustrate that the Statute of Monopolies is often fundamentally misunderstood. So what, exactly, did it actually do? It’s a tale of opportunism, corruption, and court intrigue, with some actual innovation inbetween. The whole saga ended Francis Bacon’s political career, led to a major constitutional crisis, and set the scene for how inventors were to behave and act for well over a century. In this first part, I’ll give the context you’ll need to really appreciate what was going on, and I’ll publish the rest in the weeks to come.

First off, the Statute of Monopolies was certainly not the first patent law. Venice’s senate had enacted a law on monopolies for invention as early as 1474. But even then, we shouldn’t be looking for statutes at all. The history of patents does not begin in 1474, but much earlier, with plenty of monopolies over new inventions having already been granted by the ruling grand council of Venice, and by the authorities of other Italian cities like Florence. The key thing to recognise about early patents is that they were not a creation of parliaments or their statutes, but of those in charge. They were the creation of sovereigns, a creature of kings and queens (or in the case of republics like Venice, of governing councils).

As regular readers of this newsletter might remember, patent monopolies for invention had already had long history in England, well before 1624. Patents in general were a very ordinary tool of English monarchs, used to communicate their will. By issuing letters patent, monarchs essentially issued public orders, open for everyone to see. (Think “patently”, as in clearly or obvious, which comes from the same root.) Monarchs used letters patent to grant titles and lands, appoint or remove people as officials, extend royal protections to foreign immigrants, incorporate cities, guilds, even theatre troupes — in general, just to rule.

And, eventually, English monarchs copied the Venetians by issuing letters patent to grant temporary monopolies to particular people, to encourage them to make discoveries, publish books, or introduce new industries or inventions to the realm. It’s only over the passage of centuries that we’ve come to refer to patents for invention — a mere subset of letters patent, and really even a mere subset of patent monopolies for all sorts of other creative work — as simply patents. Intellectual property was thus a ruler-granted privilege, created in the same way that a town gains the official status of a city, or a commoner becomes a knight. English monarchs began granting monopolies for discovering new territories and trade routes from 1496, for printing certain books from 1512, and for introducing new industries or inventions from 1552 (with one weird isolated exception from as early as 1449).

August 2, 2021

Who is Colt? A History of the Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company

Forgotten Weapons

Published 23 Feb 2017Today we will take a look at the history of the Colt company, from Sam Colt’s first efforts in Paterson (and before) to the West Hartford remnants that survive today. If you enjoy this type of history, please let me know in the comments!

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

Gun display racking provided by Matrix Armory: http://www.matrixarmory.com

February 2, 2021

The History of Hollywood

The Cynical Historian

Published 3 Sep 2020This episode is about the history of Hollywood, and it’s quite a long one. This is part 9 in a long running series about California history.

————————————————————

references:

Bernard F. Dick, Engulfed: The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001). https://amzn.to/3f2Yb0SHollywood’s America: United States History Through its Films, eds. Mintz, Steven and Randy Roberts (St. James, N.York: Brandywine Press, 1993). https://amzn.to/2tZIoJT

Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Atheneum Books, 1992). https://amzn.to/2KX0jI2

Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era, (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1985). https://amzn.to/2VPTbVX

————————————————————

Support the channel through PATREON: https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorian

or by purchasing MERCH: teespring.com/stores/the-cynical-hist…LET’S CONNECT:

Twitch: https://www.twitch.tv/cynicalhistorian

Discord: https://discord.gg/Ukthk4U

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

Subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/CynicalHistory/————————————————————

Wiki: By 1912, major motion-picture companies had set up production near or in Los Angeles. In the early 1900s, most motion picture patents were held by Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey, and filmmakers were often sued to stop their productions. To escape this, filmmakers began moving out west to Los Angeles, where attempts to enforce Edison’s patents were easier to evade. Also, the weather was ideal and there was quick access to various settings. Los Angeles became the capital of the film industry in the United States. The mountains, plains and low land prices made Hollywood a good place to establish film studios.

Director D. W. Griffith was the first to make a motion picture in Hollywood. His 17-minute short film In Old California (1910) was filmed for the Biograph Company. Although Hollywood banned movie theaters — of which it had none — before annexation that year, Los Angeles had no such restriction. The first film by a Hollywood studio, Nestor Motion Picture Company, was shot on October 26, 1911. The H. J. Whitley home was used as its set, and the unnamed movie was filmed in the middle of their groves at the corner of Whitley Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard.

The first studio in Hollywood, the Nestor Company, was established by the New Jersey–based Centaur Company in a roadhouse at 6121 Sunset Boulevard (the corner of Gower), in October 1911. Four major film companies – Paramount, Warner Bros., RKO, and Columbia – had studios in Hollywood, as did several minor companies and rental studios. In the 1920s, Hollywood was the fifth-largest industry in the nation. By the 1930s, Hollywood studios became fully vertically integrated, as production, distribution and exhibition was controlled by these companies, enabling Hollywood to produce 600 films per year.

Hollywood became known as Tinseltown and the “dream factory” because of the glittering image of the movie industry. Hollywood has since become a major center for film study in the United States.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #history #Hollywood #California