… once elected and inaugurated, the consuls select the day of the dilectus. Polybius is quite wordy in his description of the process, but it gives us a nice schematic vision of the process. In practice, there are two groups here to keep track of in parallel: the dilectus of Roman citizens, but also the mobilization of the socii who will reinforce those Roman legions once raised. The two processes happen at the same time.

So, on the appointed day(s), Polybius tells us all Romans liable for service of military age assemble in Rome and are called up on the Capitoline Hill for selection. This was a point that raised a lot of skepticism from historians,1 mostly concerning the number of people involved, but those concerns have all pretty much been resolved. While there might have been something like 323,000 Roman citizen males in the third or second century, they’re not all liable for general conscription, which was restricted to the iuniores – Roman citizen men between the ages of 17 and 46, who numbered fewer, probably around 228,000; seniores in theory could be conscripted, but in practice only were in an emergency. In practice the number is probably lower still as unless things were truly dire, men in their late 30s or 40s with several years of service could be pretty confident they wouldn’t be called and might as well stay home and rely on a neighbor of family member to report back in the unlikely event they were called. That’s still, of course, too many to bring up on to the Capitoline or to sort through calling out names, but as Polybius notes they don’t all come up, they’re called up by tribe. The Roman tribes were one of Rome’s two systems of voting units (the other, of centuries, we’ll come to in just a moment) and there were 35 of them, four urban tribes for those living in the city and 31 rural tribes for those living outside the city.

So what is actually happening is that the consul sets the date for the dilectus, then assigns his military tribunes to their legions (this matters because the tribunes will then do a round-robin selection of recruits to ensure each legion is of equivalent equality), then calls up one tribe at a time, with each tribe having perhaps around 6-7,000 iunores in it. Conveniently, the Capitoline is plenty large enough for that number, with estimates of its holding capacity tending to be between 12,000 and 25,000 or so.2 And while Polybius makes it seem like all of this happens on one day, it probably didn’t. Livy notes of one dilectus in 169, conducted in haste, was completed in 11 days; presumably the process was normally longer (though that’s 11 days for all three steps, not just the first one, Livy 43.14.9-10).

Once each tribe is up on the Capitoline, recruits are selected in batches; Polybius says in batches of four, but this probably means in batches equal to the number of legions being enrolled, as Polybius’ entire schema assumes a normal year with four legions being enrolled. Now Polybius doesn’t clarify how selection here would work and here Livy comes in awfully handy because we can glean little details from various points in his narrative (the work of doing this is a big chunk of Pearson (2021), whose reconstruction I follow here because I think it is correct). We know that the censors compile a list not just of Roman senators but of all Roman citizen households, including self-reported wealth and the number of members in the household, updated every five years. That self-reported wealth is used to slot Romans into voting centuries, the other Roman voting unit, the comitia centuriata; those centuries correspond neatly to how Romans serve in the army, with the equites and five classes of pedites (infantry). Because of a quirk of the Roman system, the top slice of the top class of pedites also serve on horseback, and Polybius is conveniently explicit that the censors select and record this too.

So at dilectus time, the consuls, their military tribunes (and their state-supplied clerk, a scriba) have a list of every Roman citizen liable for conscription, with the century and tribe they belong to, the former telling you what kind of soldier they can afford to be when called and the latter what group they’ll be called in. And we know from other sources (Valerius Maximus 6.3.4) that names are being read out, rather than just, say, selecting men at sight out of a crowd. That actually makes a lot of sense as dilectus (“select”) may really be dis-lego, “read apart”, from lego (-ere, legi, lectum) “to read”.3 And that matters because the other thing the Romans clearly have a record of us who has served in the past. We know that because in an episode that is both quite famous but also really important for understanding this process, in 214 – after four of the most demanding years of military activity in Roman history, due to the Second Punic War – the Roman censors identified 2,000 Roman iuniores who had not served in the previous four years (or claimed and been granted an exemption), struck them from the census rolls (in effect, revoking their citizenship) and then packed them off to serve as infantry (regardless of their wealth) in Sicily.4

So what happens as each tribe comes up is that the tribunes can call out the names – in batches – of men with the least amount of service, of the particular wealth categories they are going to need to fill out the combat roles in the legion.5 The tribunes for each legion pick one recruit from each batch that comes up, going round-robin so every legion gets the same number of first-picks. Presumably once the necessary fellows are picked out of one tribe, that tribe is sent down the Capitoline and the next called up.

Once that is done the oath is administered. This oath is the sacramentum militare; we do not have its text in the Republic (we do have the text for the imperial period), but Polybius summarizes its content that soldiers swear to obey the orders of the consuls and to execute them as best they are able. The Romans, being practical, have one soldier swear the full oath and then every other soldier come up and say, “like that guy said” (I’m not even really joking, see Polyb. 6.21.3) to get everyone all sworn in. Of course such an oath is a religious matter and so understood to be quite binding.

Then the tribunes fix a day for all of the new recruits to present themselves again (without arms, Polybius specifies) and dismiss them. Strikingly, Polybius only says they are dismissed at this point – not, as later, dismissed to their homes. This makes me assume that the oath being described is administered tribe by tribe before the tribe is sent down (this also seems likely because fitting the last tribe and four legions worth of recruits on the Capitoline starts to get pretty tight, space-wise). Selecting with the various tribes might, after all, take a couple of days, so the tribunes might be telling the recruits of the first few tribes what day the entire legion will be assembled (that’ll be Phase II) after they’ve worked through all of the tribes. Meanwhile, once your tribe was called, you didn’t have to hang around in Rome any longer, if you weren’t selected you could go home, while the picked recruits might stick around in Rome waiting for Phase II.

That leads to the other logistical question for Phase I: the feasibility of having basically all of the iuniores in Rome for the process. Doubts about this have led to the suggestion that perhaps the dilectus in Rome was mirrored by smaller versions held in other areas of Roman territory in Italy (the ager Romanus) for Roman citizens out there. The problem with that assumption is that the text doesn’t support it. The Romans send out conscription officers (conquisitores) exactly twice that we know of, in 213 and 212 (Livy 23.32.19 and 25.5.5-9) and these are clearly exceptional responses to the failure of the dilectus in the darkest days of the Second Punic War (the latter is empowered to recruit under-age boys if they look strong enough to bear arms, for instance). But I also think it was probably unnecessary: this was a regular occurrence, so people would know to make arrangements for it and the city of Rome could prepare for the sudden influx of young men. This is, after all, also a city with regular “market days”, (the nundinae) which presumably would also cause the population to briefly swell, though not as much. And we’re doing this in an off-time in the agricultural calendar, so the farmhands can be spared.

Moreover, Rome isn’t that far away for most Romans. Strikingly, when the Romans do send out conquisitores, they split them with half working within 50 miles of Rome and half beyond that (Livy 25.5.5-9). The implication – that most of the recruits to be found are going to be within that 50 mile radius – is clear, and it makes a lot of sense given the layout of the ager Romanus. Certainly there were communities of Roman citizens farther out, but evidently not so many. Fifty miles down decent roads is a two-day walk; short enough that Roman iuniores could fill a sack with provisions, walk all the way to Rome, stay a few days for the first phase of the dilectus and walk all the way back home again at the end. We’re not told how communities farther afield might handle it, but they may well have trekked in too, or else perhaps sent a few young men with instructions to bring back a list of everyone who was called.

Meanwhile the other part of this phase is happening: the socii. Polybius reports that “at the same time the consuls send their orders to allied cities in Italy, which they with to contribute troops, stating the numbers required and the day and place at which the men selected must present themselves.”6 Livy gives us more clarity on how this would be done, providing in his description of the muster of 193 the neat detail that representatives of the communities of socii met with the consuls on the Capitoline (Livy 34.36.5). And that makes a ton of sense – this is happening at the same time as the selection, so that’s where the consuls are.

We also know the consuls have another document, the formula togatorum, which spells out the liability of each community of socii for recruits; we know less about this document than we might like. Polybius tells us that the socii were supposed to compile lists of men liable for recruitment (Polyb. 2.23-4) and an inscription of the Lex Agraria of 111 BC refers to, “the allies or members of the Latin name, from whom the Romans are accustomed to demand soldiers in the land of Italy ex formula togatorum“.7 That then supplies us with a name for the document. Finally, we know that in 177, some of the socii complained that many of the households in their territory had migrated into other communities but that they conscription obligations had not been changed (Livy 41.8), which tells us there was a formal system of obligations and it seems to have been written down in something called the formula togatorum, to which Polybius alludes.

What was written down? Really, we don’t know. It has been suggested that it might have been a sliding scale of obligations (“for every X number of Romans, recruit Y number of Paeligni”) or a standard total (“every year, recruit Y Paeligni”) or a maximum (“the total number of Paeligni we can demand is Y, plus one more guy whose job is to throw flags at things”.). In practice, it was clearly flexible,8 which makes me suspect it was perhaps a list of maximum capabilities from which the consuls could easily compute a fair enough distribution of service demands. A pure ratio doesn’t make much sense to me, because the socii come in their own units, which probably had normal sizes to them.

So, while the military tribunes are handling the recruitment of citizens into the legions, the consuls are right there, but probably focused on meeting with representatives of each community of the socii and telling them how many men Rome will need this year. Once told, those representatives are sent back to their communities, who handle recruitment on their own; Rome retains no conscription apparatus among the socii – no conscription offices, no records or census officials, nada. The consuls spell out how many troops they need and the rest of it was the socii‘s elected official’s problem.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How To Raise a Roman Army: The Dilectus“, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-16.

1. Particularly in P.A. Brunt, Italian Manpower (1971).

2. Pearson (2021) compiles them; the issue is also discussed in Taylor (2020).

3. The philological argument here is Pearson (2021), 16-17. It is not air-tight because legere has a lot of meanings, including “to pick out” along with “to read”. That said, given that the verb of being recruited into the army is conscribere (“to write together, to conscript”), there really is a strong implication that this is a process with written records, which the rest of the evidence confirms. I think Pearson may or may not be right about the understood meaning of dilectus implying writing, but the process surely involved written records, as she argues.

4. A punishment post, this is also where the survivors of the Battle of Cannae were sent. Both groups remain stuck in Sicily until pulled into Scipio Africanus’ expedition to Africa in 205, so these fellows don’t get to go home and get their citizenship back until the conclusion of the war in 201.

5. In particular, we generally assume the lowest classes of Roman pedites probably could only afford to serve as light troops, the velites, while the wealthy equites had their own selection procedure for the cavalry done first. Of course, rich Romans not selected for the cavalry might serve as infantrymen if registered in the centuries of pedites which is presumably how Marcus Cato, son of the Censor, ends up in the infantry at Pydna (Plut. Aem. 21).

6. Polyb. 6.21.4. Paton’s trans.

7. Crawford, Roman Statutes (1996), 118 for the text of that inscription.

8. Something pointed out by L. de Ligt in his chapter in the Blackwell A Companion to the Roman Army (2007).

May 15, 2024

QotD: Recruiting an army in the Roman Republic

May 13, 2024

Roman Legions – Sometimes found all at sea!

Drachinifel

Published Feb 2, 2024Today we take a quick look at some of the maritime highlights of the new special exhibition at the British Museum about the Roman Legions:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/exhibit…

(more…)

May 6, 2024

The Canadian Army defiles updates its online branding

Shady Maples isn’t too impressed with the new corporate image “icon” the Canadian Army extruded onto their TwitX account last week:

The Canadian Army’s dysenteric moose shitting itself to death, er, I mean “The Canadian Army’s latest supplementary icon for online use”

The Canadian Army needs to get its shit together on Twitter, not because Twitter is important, but because people believe that Twitter is important. If you follow official accounts, then you’re probably tracking the Army’s latest update to its corporate branding.

Within hours the Army was

furiously backpedalingclarifying that our new digitalized Rorschach test wasn’t a replacement logo, but an “icon” that “will be used in the bottom left corner of certain communications products and in animations for videos”. This was a bigger news event than the announcement itself.When I first saw this thing, I thought it was a maple leaf blowing past north Africa. Could this be Straussian commentary on our National Defence Strategy? Perhaps, but now thanks to Twitter all I see when I look at it is a dysenteric moose shitting itself to death (and now you do too).

The hook in all this isn’t the new branding, which is just a drop in CAF’s vast ocean of PowerPoint phluff, the visual equivalent of white noise. It’s also not in the backlash either, because that’s just another Tuesday on Twitter. You see, unlike the Iranian nuclear program or whatever’s happening between Drake and Kendrick Lamar, the CAF is not a topic of serious international concern.

Come for the mocking of the icon, stay for the contrasting social media appearances of Canadian and Israeli Lieutenants General.

April 30, 2024

QotD: The ambitious Roman’s path to glory and riches

The Romans, for one, admitted all the time that they screwed up … to themselves, in private (what passed for “private” in the ancient world, anyway). A big reason an ambitious man (a redundancy in ancient Rome) wanted to climb the cursus honorum was because that was the easiest way to get a field command, which was the easiest way to start a war with someone, which was the easiest route to riches and glory … provided you didn’t fuck it up. But if you did, the best thing to do was to go down fighting with your legions, because the minute you got back to Rome, there’d be ambitious men (again: redundant in context) lined up from here to Sicily waiting to prosecute your ass for something, anything — “losing a war” wasn’t a crime in itself, but whatever the official charge (usually “corruption” or “misuse of public funds” or something), everyone knew you were really getting punished for losing.

At no point, however, did the putative justification for war come into play. Picking a war with the Parthians wasn’t bad in itself. Nor was “picking a war with the Parthians because you gots to get paid”. Certainly picking a war with, say, the Gauls wasn’t bad in itself, and “picking a war with the Gauls because I need to capture and sell a few thousand slaves to cover my debts” was so far from being bad, guys like Caesar, if I recall my Gallic Wars correctly, openly declared it from jump street. And though Caesar surely would’ve been prosecuted if he’d lost, and Crassus if he’d lived, suggesting that anyone owed an apology to the Gauls or Parthians would’ve gotten you locked up as a dangerous lunatic.

A confident, manly power might lose a war or two. Hell, they might lose a bunch — the Romans got beat all the time, and so did the British. But no matter how bad the loss, or how embarrassing the peace treaty, they shrugged it off. You win some, you lose some, and when it’s clear you’re going to lose — or when it becomes clear that there’s no possible way “victory” will ever be worth the cost — you cut your losses and came home. HM forces, for instance, lost no less than three wars in Afghanistan. And so what? Great Britain was still the world’s preeminent power. They never even dreamed of apologizing — that’s the Great Game, old sock.

Severian, “Friday Mailbag / Grab Bag”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-07-23.

April 26, 2024

The British Army from the start of the Cold War

Dr. Robert Lyman discusses the state of the British Army through the Cold War years down to today, with emphasis on the defence budget tracking against perceived threats to the UK and allies over that period:

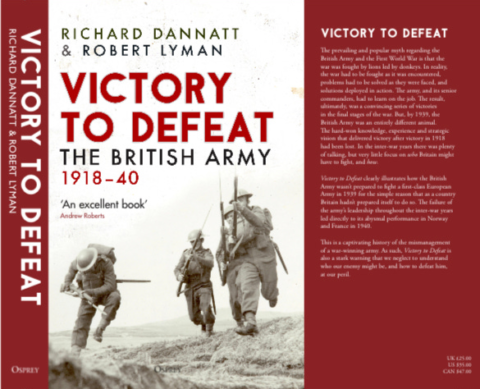

Last year General Lord Dannatt and I published an account of the British Army between 1918 — when it achieved a great victory — and 1940, when it did not. The book was written in part to challenge the UK to think seriously about what happens when our country neglects the requirement for an army able to fight at a high-intensity for a prolonged period against a peer adversary.

Part of our argument was to look at the amount of money the country spends on its defence as a barometer of the seriousness or otherwise of our political masters towards spending money on the primary duty of government, namely the security of its citizens. Our fear is that in the rampant feel-goodery that has plagued the West since 1991 the harsh realities of our unstable world have become forgotten. It has taken Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and Russia’s subsequent bludgeoning of that benighted country for politicians to gradually wake up to the scale of the threat that this sort of instability offers to the world, not merely Europe or the West.

My fear, like that of many others, is that the wake-up call is taking too long and our country’s defences remain in a parlous state. We haven’t had an army able to deploy at divisional level or above in sustained all-arms manoeuvre for perhaps ten years or more. In other words, our ability to provide what our forefathers would have described as a robust “continental commitment” is almost non-existent.

In the book we trace the origins of the failure to think seriously about the need to have a deployable, expeditionary army, able to fight and operate alongside its allies in NATO on an all-arms battlefield. The reality is that the Cold War forced Britain to retain the ability to fight a general war in Europe, all the while finding the resources to undertake its other commitments across the world. Although worldwide events were dynamic from 1945 to 1989 with further conflicts for the United Kingdom in Malaya, Dhofar, Cyprus, Kenya, Borneo, the Falklands, and the long-running Troubles in Northern Ireland, it was the Cold War in Europe that principally drove the defence agenda and kept the budget at around 5 per cent of GDP. As the major bridge between the United States and Europe, the Royal Navy was heavily committed above and below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean to keep open the sea lines of communication to NATO’s dominant partner, while the British Army retained some 55,000 troops in four armoured divisions as part of NATO’s Northern Army Group and the Royal Air Force was also largely forward-based in West Germany as part of the Second Allied Tactical Air Force. These conventional deployments were all conducted under the nuclear umbrella of Mutual Assured Destruction. By the 1980s, with the West under the leadership of US President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and with increased spending on both conventional armaments and the highly experimental Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile Defence system, the strain of strategic military competition began to show on the political and economic stability of the Soviet Union. Despite the perestroika political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the associated openness of glasnost under General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, the cracks in the Berlin Wall that opened on 9 November 1989 led inexorably to the collapse of the Soviet Union two years later and the old flag of Russia being raised over the Kremlin on 26 December 1991. The Cold War was over, and an apparent New World Order had begun. The historian Francis Fukuyama declared – somewhat ambitiously – the end of history.

It was at this point that international leaders and their finance ministers in the West began to overlook the cautionary tale that the history of the 20th century might have taught them. With the Soviet Union gone and rump Russia apparently enfeebled, Western states eagerly embarked on military reduction and a peace dividend. In the United Kingdom, the “Options for Change” exercise saw a major slashing of defence capability, beneficially coincidental to help ameliorate a significant economic downturn. The British Army was reduced from 155,000 to 116,000 soldiers, notwithstanding the first Gulf War of 1990–91 which many wishful thinkers regarded as something of an aberration. However, despite that war and the subsequent deployment of large parts of the armed forces to Bosnia from 1992 and then to Kosovo in 1999, the new Labour government of Prime Minister Tony Blair continued with the implementation of its Strategic Defence Review of 1997–98. As a piece of policy work, this was considered an honest review of the United Kingdom’s defence policy and a progressive blueprint for future defence planning and expenditure. Endorsed by Tony Blair and the Chiefs of Staff, this review might have stood the nation in good stead for the future had the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, fully funded its outcome. For his own reasons, he chose not to do so. The underfunding of the United Kingdom’s defence capability began to show its deficiencies a year after with the second Gulf War of 2003, and the situation was then exacerbated by a protracted campaign in Iraq for the British Army lasting until 2009 and an even more intense one in Afghanistan lasting until 2014.

April 20, 2024

Cape Esperance and the Japanese Evacuation of Guadalcanal

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 12, 2024Today we return to Guadalcanal, to the site of the last actions of the campaign. For the Japanese, the defeat at Edson’s Ridge (aka Bloody Ridge) forced a disastrous and uncoordinated retreat into the jungle. With their supply lines destroyed, Japanese troops largely moved west on the island, away from American positions and in search of food. This would eventually bring them to Cape Esperance, where a rearguard force was landed, and some 10,652 Japanese soldiers were successfully evacuated on fast-moving destroyers over the course of several nights in early February, 1943.

On the American side, Army troops landed to relieve the Marines. In January and into early February they ran what was considered a mopping-up campaign west, including landings on the far west end of the island beyond Esperance. The intention was to encircle the remaining Japanese forces, under the assumption that the destroyer activity was landing fresh troops. Instead, when the American forces joined up at Cape Esperance it was an anticlimactic end to the fighting, as all they found were remnants of equipment that had been left on the beaches.

(more…)

April 18, 2024

What to do if Romans Sack your City

toldinstone

Published Jan 12, 2024Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:34 Progress of a siege

1:55 Looting and violence

3:42 Recorded atrocities

4:45 Captives

5:27 BetterHelp

6:36 Surviving a Roman sack

7:13 Where to hide

8:27 What to do if you’re captured

9:20 Advice for women

10:09 The fate of captives

(more…)

April 14, 2024

QotD: Imperium in the Roman Republic

What connects these offices in particular is that they confer imperium, a distinctive concept in Roman law and governance. The word imperium derives from the verb impero, “to command, order” and so in a sense imperium simply means “command”, but in its implication it is broader. Imperium was understood to be the power of the king (Cic. Leg. 3.8), encompassing both the judicial role of the king in resolving disputes and the military role of the king in leading the army. In this sense, imperium is the power to deploy violence on behalf of the community: both internal (judicial) violence and external (military) violence.

That power was represented visually around the person of magistrates with imperium through the lictors (Latin: lictores), attendants who follows magistrates with imperium, mostly to add dignity to the office but who also could act as the magistrate’s “muscle” if necessary. The lictors carried the fasces, a set of sticks bundled together in a rod; often in modern depictions the bundle is thick and short but in ancient artwork it is long and thin, the ancient equivalent of a policeman’s less-lethal billy club. That, notionally non-lethal but still violent, configuration represented the imperium-bearing magistrate’s civil power within the pomerium (recall, this is the sacred boundary of the city). When passing beyond the pomerium, an axe was inserted into the bundle, turning the non-lethal crowd-control device into a lethal weapon, reflective of the greater power of the imperium-bearing magistrate to act with unilateral military violence outside of Rome (though to be clear the consul couldn’t just murder you because you were on your farm; this is symbolism). The consuls were each assigned 12 lictors, while praetors got six. Pro-magistrates [proconsuls and propraetors] had one fewer lictor than their magistrate versions to reflect that, while they wielded imperium, it was of an inferior sort to the actual magistrate of the year.

What is notable about the Roman concept of imperium is that it is a single, unitary thing: multiple magistrates can have imperium, you can have greater or lesser forms of imperium, but you cannot break apart the component elements of imperium.1 This is a real difference from the polis, where the standard structure was to take the three components of royal power (religious, judicial and military) and split them up between different magistrates or boards in order to avoid any one figure being too powerful. For the Romans, the royal authority over judicial and military matters were unavoidably linked because they were the same thing, imperium, and so could not be separated. That in turn leads to Polybius’ awe at the power wielded by Roman magistrates, particularly the consuls (Polyb. 6.12); a polis wouldn’t generally focus so much power into a single set of hands constitutionally (keeping in mind that tyrants are extra-constitutional figures).

So what does imperium empower a magistrate to do? All magistrates have potestas, the power to act on behalf of the community within their sphere of influence. Imperium is the subset of magisterial potestas which covers the provision of violence for the community and it comes in two forms: the power to raise and lead armies and the power to organize and oversee courts. Now we normally think of these powers as cut by that domi et militiae (“at home and on military service”) distinction we discussed earlier in the series: at home imperium is the power to organize courts (which are generally jury courts, though for some matters magistrates might make a summary judgement) and abroad the power to organize armies. But as we’ll see when we get to the role of magistrates and pro-magistrates in the provinces, the power of legal judgement conferred by imperium is, if anything, more intense outside of Rome. That said it is absolutely the case that imperium is restrained within the pomerium and far less restrained outside of it.

There were limits on the ability of a magistrate with imperium to deploy violence within the pomerium against citizens. The Lex Valeria, dating to the very beginning of the res publica stipulated that in the case of certain punishments (death or flogging), the victim had the right of provocatio to call upon the judgement of the Roman people, through either an assembly or a jury trial. That limit to the consul’s ability to use violence was reinforced by the leges Porciae (passed in the 190s and 180s), which protected civilian citizens from summary violence from magistrates, even when outside of Rome. That said, on campaign – that is, militae rather than domi – these laws did not exempt citizen soldiers from beating or even execution as a part of military discipline and indeed Roman military discipline struck Polybius – himself an experienced Greek military man – as harsh (Polyb. 6.35-39).

In practice then, the ability of a magistrate to utilize imperium within Rome was hemmed in by the laws, whereas when out in the provinces on campaign it was far less limited. A second power, coercitio or “coercion” – the power of a higher magistrate to use minor punishments or force to protect public order – is sometimes presented as a distinct power of the magistrates, but I tend to agree with Lintott (op. cit., 97-8) that this rather overrates the importance of the coercive powers of magistrates within the pomerium; in any case, the day-to-day maintenance of public order generally fell to minor magistrates.

While imperium was a “complete package” as it were, the Romans clearly understood certain figures as having an imperium that outranked others, thus dictators could order consuls, who could order praetors, the hierarchy neatly visualized by the number of lictors each had. This could create problems, of course, when Rome’s informal systems of hierarchy conflicted with this formal system, for instance at the Battle of Arausio, the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio refused to take orders from the consul, Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, because the latter was his social inferior (being a novus homo, a “new man” from a family that hadn’t yet been in the Senate and thus not a member of the nobiles), despite the fact that by law the imperium of a sitting consul outranked that of a pro-consul. The result of that bit of insubordination was a military catastrophe that got both commanders later charged and exiled.

Finally, a vocabulary note: it would be reasonable to assume that the Latin word for a person with imperium would be imperator2 because that’s the standard way Latin words form. And I will say, from the perspective of a person who has to decide at the beginning of each thing I write what circumlocution I am going to use to describe “magistrate or pro-magistrate with imperium“, it would be remarkably fortunate if imperator meant that, but it doesn’t. Instead, imperator in Latin ends up swallowed by its idiomatic meaning of “victorious general”, as it was normal in the republic for armies to proclaim their general as imperator after a major victory (which set the general up to request a triumph from the Senate). In the imperial period, this leads to the emperors monopolizing the term, as all of the armies of Rome operated under their imperium and thus all victory accolades belonged to the emperor. That in turn leads to imperator becoming part of the imperial title, from where it gives us our word “emperor”.

That said, the circumlocution I am going to use here, because this isn’t a formal genre and I can, is “imperium-haver”. I desperately wish I could use that in peer reviewed articles, but I fear no editor would let me (while Reviewer 2 will predictably object to “general”, “commander” or “governor” for all being modern coinages).3

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Part IIIb: Imperium”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-08-18.

1. I should note here that Drogula (in Commanders and Command (2015)) understands imperium a bit differently than this more traditional version I am presenting (in line with Lintott’s understanding). He contends that imperium was an entirely military power which was not necessary for judicial functions and was not only indivisible but also, at least early on, did not come in different degrees. In practice, I’m not sure the Romans were ever so precise with their concepts as Drogula wants them to be.

2. Pronunication note because this bothers me when I hear this word in popular media: it is not imPERator, but impeRAtor, because that “a” is long by nature, and thus keeps the stress.

3. And yes, really, I have had reviewers object to “general” or “commander” to mean “the magistrate or pro-magistrate with imperium in the province”. There is no pleasing Reviewer 2.

April 7, 2024

Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain (1942)

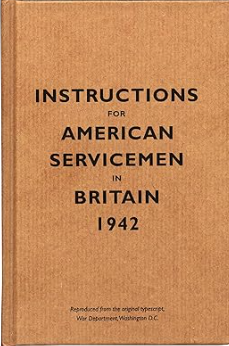

Henry Getley on the US War Department publication Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain produced for incoming GIs on arrival in Britain from early in 1942:

[W]ith their troops pouring into this country from 1942 onwards to prepare for D-Day, officials at the US War Department did their best to make the culture clash as trouble-free as possible. One of their main efforts was issuing GIs with a seven-page foolscap leaflet called Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain.

It’s available in reprint as a booklet and makes fascinating reading, not least for its straightforward, jargon-free writing style and its overriding message – telling the Yanks to use “plain common horse sense” in their dealings with the British.

In parts, it now seems clumsy and condescending. But its purpose was praiseworthy – to try to get American troops to damp down the impression that they were overpaid, oversexed and over here. Many GIs qualified in all three aspects, of course, but you couldn’t blame the top brass for trying.

The leaflet paints a sympathetic (some would say patronising) picture for the incoming Americans of a Britain – “a small crowded island of forty-five million people” – that had been at war for three years, having initially stood alone against Hitler and braved the Blitz. Hence this “cradle of democracy” was now a “shop-worn and grimy” land of rationing, the blackout, shortages and austerity. But beneath the shabbiness, there was steel.

The British are tough. Don’t be misled by the British tendency to be soft-spoken and polite. If need be, they can be plenty tough. The English language didn’t spread across the oceans and over the mountains and jungles and swamps of the world because these people were panty-waists.

There were helpful hints about cricket, football, darts, pounds, shillings and pence, warm beer and badly-made coffee. And because we are two nations divided by a common language, the Yanks were urged to listen to the BBC.

In England the “upper crust” speak pretty much alike. You will hear the newscaster for the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). He is a good example, because he has been trained to talk with the “cultured” accent. He will drop the letter “r” (as people do in some sections of our own country) and will say “hyah” instead of “here”. He will use the broad “a”, pronouncing all the a’s in “banana” like the “a” in father.

However funny you may think this is, you will be able to understand people who talk this way and they will be able to understand you. And you will soon get over thinking it’s funny. You will have more difficulty with some of the local accents. It may comfort you to know that a farmer or villager from Cornwall very often can’t understand a farmer or villager in Yorkshire or Lancashire.

The GIs were warned against bravado and bragging, being told that the British were reserved but not unfriendly. “They will welcome you as friends and allies, but remember that crossing the ocean doesn’t automatically make you a hero. There are housewives in aprons and youngsters in knee pants in Britain who have lived through more high explosives in air raids than many soldiers saw in first-class barrages during the last war.”

April 3, 2024

Man of his era, indeed – “we think too much of Thomas Jefferson, because we don’t see his cultural context”

Chris Bray on the sudden discovery of his dissertation topic in a quite unexpected venue:

Fifteen years ago, more or less, I stumbled into a topic for a dissertation when I got frustrated and took a walk. I was in Worcester, Massachusetts, working in the archives at the American Antiquarian Society and finding just absolutely nothing at all that answered my question. So I wandered, and passed a decommissioned armory with a sign over the door that said MASSACHUSETTS MILITARY ARCHIVES. They let me poke around, and by the end of the day I was running around with my hair on fire and shouting at everybody that my dissertation was about something else, now.

State militia courts-martial in the opening decades of a new republic recorded every word, in transcripts that could run to hundreds of pages — frequently interspersed with a line that said something like, “Clerk again reminded witnesses to speak slowly.” The dozen officers who made up a militia court weren’t military professionals, but were instead the prominent farmers and craftsmen who were elected to militia office by their townsmen. So transcripts of state military trials were verbatim discussions among something like the most respected farmers of a county, or of this county and the next one over. They were not recorded debates between the great statesmen of the era. And they needed a big room where a dozen men could sit at a long table in front of the parties and the spectators, so state courts-martial tended to convene in taverns.

One more important thing: The formalization of military courts was way in the future, and there wasn’t a professional JAG Corps in the militia to run trials. State courts-martial were a lawyer-free forum. The accuser was expected to “prosecute” his case — to show up and prove the wrongdoing he had claimed to know about. And defendants were expected to personally defend themselves, questioning witnesses and presenting arguments to the court. At the end of testimony, the “prosecutor” and the defendant personally went home to write their own closing statements, and we still have these documents, tied into the back of the trial transcripts with a ribbon. Courts would stop in the evening and resume in the morning, and men accused of military offenses would show up with twenty-page closing statements in their own handwriting, with holes in the page where the pen poked through.

So: a panel of farmers, serving as local militia officers, listening to an argument between farmers who served as local militia officers, in a tavern, and we have a detailed record of every word they said.

They were magnificent. They were clear, thoughtful, fair, and logical. They had no patience at all for dithering or innuendo; they expected a man who accused another man of wrongdoing to get to it, in an ordered and serious way. Witnesses who fudged or evaded ran into a buzzsaw. The officers on the courts would interject with their own questions: Look, captain, did he say it or didn’t he? And then they wanted a serious summary of the evidence, with a consistent argument. Their thinking was structured, and they expected the same of others.

We distinguish between talking and doing, and between talkers and doers. But these men were doers in the hardest sense. Their families starved or thrived because of their work with tools and the skill in their hands. Their food came from their dirt, outside their front door. They mostly weren’t formally educated; they didn’t spend their young lives going to school. They worked, from childhood. And yet they could talk, meaningfully and carefully. They could address a controversy with measured discourse, gathering as a community to assess an institutional failure and organize a logical response. Their talking was another way of doing.

The historian Pauline Maier has written that we think too much of Thomas Jefferson, because we don’t see his cultural context. The Declaration of Independence looks to us like a startling act of political creativity, systematically describing a set of grievances and proposing an ordered response based on a clear philosophy of action. But Jefferson showed up after years of disciplined and thoughtful local proclamations on the crisis, Maier says. He was the national version of a hundred skillful town conventions, standing on the foundation of an ordered society that knew what it believed and what it meant to do about it.

March 27, 2024

Civil Defence is a real thing in Finland

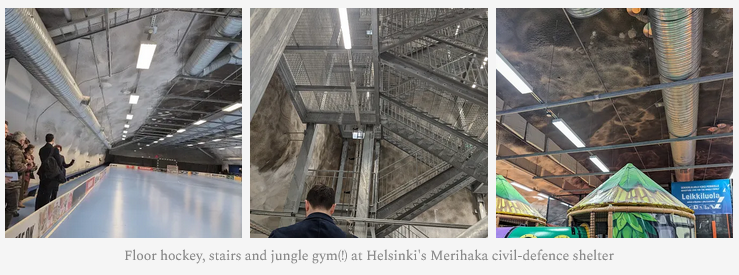

Paul Wells reports back on his recent trip to Finland, where he got to tour one of the big civil-defence shelters in Helsinki:

One of the best playgrounds for children in Helsinki is the size of three NFL football fields, dug into bedrock 25 metres below a street-level car park, and built to survive a nuclear bomb.

The air down here is surprisingly fresh. The floor-hockey rinks — there are two, laid end to end — are well maintained. The refreshment stands are stocked with snacks. The steel blast doors are so massive it takes two people to slam one shut.

Finland has been building civil-defence shelters, methodically and without fuss, since the late 1950s. This one under the Merihaka residential district has room for 6,000 people. It’s so impressive that it’s the Finnish capital’s unofficial media shelter, the one visiting reporters are likeliest to be shown. The snack bar and the jungle gym are not for show, however: as a matter of government policy, every shelter must have a second, ordinary-world vocation, to ensure it gets used and, therefore, maintained between crises.

The Merihaka shelter was one of the stops on my visit to Helsinki last week. The first anniversary of Finland’s membership in NATO, the transatlantic defence alliance, is next week, on April 4. Finland’s foreign office invited journalists from several NATO countries to visit Helsinki to update us on Finland’s defence situation. I covered my air travel and hotel. Or rather, paid subscribers to this newsletter did. Your support makes this sort of work possible. I’m always grateful.

The Finnish government used to build most of the shelters. But since 2011, the law has required that new shelters be built at the owners’ expense, by owners of buildings larger than 1,200 square metres and industrial buildings larger than 1,500 square metres.

The city of Helsinki has more shelter space than it has people, including visitors from out of town. Across the country the supply is a little tighter. Altogether today Finland has a total of 50,500 shelters with room for 4.8 million people.

That’s not enough for the 5.5 million people in Finland. But then, if war ever comes, much of the population won’t need shelter, because they’ll be staying groundside to fight.

Conscription is universal for Finnish men between 18 and 60. (Women have been enlisting on a voluntary basis since the 1990s.) The standing armed forces, 24,000, aren’t all that big. But everyone who finishes their compulsory service is in the reserves for decades after, with frequent training to keep up their readiness. In a war the army can surge to 280,000. In a big war, bigger still.

The Soviet Union invaded Finland in 1939, during what was, in most other respects, the “phony war” phase of the Second World War. The Finnish army inflicted perhaps five times as many casualties on the Soviets as they suffered, but the country lost 9% of its territory and has no interest in losing more. Finland’s foreign policy since then has been based on the overriding importance of avoiding a Russian invasion.

QotD: Roman imperial strategy

There’s a useful term in the modern study of international relations, called “escalation dominance”. What escalation dominance means is that in any sort of conflict, there’s a big game theoretic advantage to being the one who decides how nasty it’s going to be. Ancient wars usually moved slowly up a ladder of escalation, from dudes yelling insults at each other across the border, to some light raiding and looting, to serious affairs where armies made an actual effort to kill and subjugate each other or conquer land.1 Highly mobile forces tended to work best at the lower rungs of the escalation ladder, and Rome frequently allowed conflicts to stay simmering at this level. But the existence and loyalty of the legions meant that it was their choice to do so, because they could also choose to slowly and inexorably march towards your capital city killing everything in their path and doing something truly unhinged when they got there, like building multiple rings of fortifications or a giant crazy siege ramp in the desert. And, paradoxically, the fact that they could do this meant that they didn’t have to as often. Thus the threat of disproportionate escalation became the ultimate economizing measure, by preventing wars from breaking out in the first place.

If deterrence fails and you have to fight, then the next best way to economize on force is by making somebody else do the fighting for you. In the late Republic and early Empire, much of Roman territory wasn’t “officially” under Roman rule. Instead, it was the preserve of dozens of petty and not-so-petty kingdoms that, on paper at least, were fully independent and co-equal sovereign entities.2 Rome actually went to some effort to keep up the charade: the client rulers were commonly referred to as “allies” [socii], and Rome took care never to directly tax or conscript their citizens. But, to be clear, it was a charade. If any of these “allies” ever wanted to leave the alliance or conduct any sort of independent foreign policy, he would not continue to be a king for long. Oftentimes the legions wouldn’t even have to show up — the terrified citizens of the client kingdom would overthrow and execute their wayward ruler themselves, in the hopes that Rome might thereby be induced not to make an example of the citizenry.

What was the point of all of this complicated kabuki theater? Once again, it’s about economy of force, this time on both the “input” and the “output” sides of the great machine of the state. On the input side: efficient government is hard to scale. Roman provincial governors were legendarily corrupt, and could get up to all kinds of mischief out there without supervision. Having a Roman ruling a whole bunch of non-Romans was also bound to cause resentment: it could lead to rebellions, or worse, tax-evasion. All of these problems were solved by pretending to have the barbarians be ruled by one of their own, a barbarian king. He could collect the taxes, and suppress revolts, and generally keep an eye on things. Moreover, as a fellow barbarian, he would know better how to keep his subjects in line, and would be less likely to commit an awkward cultural blunder. On the output side, he could also deal with border raids and other low-intensity threats. This exponentially magnified Roman military power, because it meant that instead of being stuck on garrison duty, spread out along the frontiers, the legions could be concentrated in a strategic reserve. They could then be deployed for “high intensity” operations in some remote part of the empire without worrying that they were thereby leaving the borders unguarded: operations like conquering new lands, or persuading a rebellious client kingdom that their interests lay with Rome.

If you can’t make somebody else do the fighting, then the next, next best thing is to carefully choose the time, circumstances, and location of the fight. Ideally you would muster a heavy concentration of your own forces and confront the enemy while they’re still dispersed. Ideally the ground would be thoroughly surveyed, well understood, and perhaps even prepared with static defenses. Ideally your own forces would have ample supply and good lines of communication, and your opponent would have neither of these things. It was to all these ends that in the second of the periods Luttwak surveys, the Romans built the limes3 — a massive system of defensive emplacements. These extended for thousands of miles around almost the entire frontier of the empire, but the most famous portion was Hadrian’s Wall.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire by Edward Luttwak”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-11-13.

1. This is actually also true of modern wars, and if you think you have an exception in mind, you may just not know the history that well. For instance, the current war in the Donbass wasn’t really a surprise invasion, but is best viewed as the latest and most violent stage of a conflict that’s been slowly ratcheting up for a decade.

2. Were you ever confused by who exactly this King Herod guy in the Gospel stories was? Why was there a king and also a Roman governor? He was precisely one of these client rulers!

3. Pronounced “lee-mays”, not like the fruit.

March 14, 2024

QotD: Recruiting an army in the Roman Republic

Before we dive in, we should stop to clarify some of our key actors here, the Roman magistrates and officers with a role in all of this. A Roman army consisted of one or more legions, supported by a number (usually two) alae recruited from Rome’s Italian allies, the socii. Legions in the Republic did not have specific commanders, rather the whole army was commanded by a single magistrate with imperium (the power to command armies and organize courts). That magistrate was usually a consul (of which there were two every year), but praetors and dictators,1 all had imperium and so might lead an army. Generally the consuls lead the main two armies. When more commanders were needed, former consuls and praetors might be delegated the job as a stand-in for the current magistrates, these were called pro-consuls and pro-praetors (or collectively, “pro-magistrates”) and they had imperium too.

In addition to the imperium-haver leading the army, there were also a set of staff officers called military tribunes, important to the process. These fellows don’t have command of a specific part of the legion, but are “officers without portfolio”, handling whatever the imperium-haver wants handled; at times they may have command of part of a legion or all of one legion. Finally, there’s one more major magistrate in the army: the quaestor. A much more junior magistrate than the imperium-haver (but senior to the tribunes), he handles pay and probably in this period also supply. That said, the quaestor is not usually the general’s “number two” even though it seems like he might be; quaestors are quite junior magistrates and the imperium-haver has probably brought friends or advisors with a lot more experience than his quaestor (who may or may not be someone the imperium-haver knows or likes). […]

The first thing to note about this process, before we even start is that the dilectus was a regular process which happened every year at a regular time. The Romans did have a system to rapidly raise new troops in an emergency (it was called a tumultus), where the main officials, the consuls, could just grab any citizen into their army in a major emergency. But emergencies like that were very rare; for the most part the Roman army was filled out by the regular process of the dilectus, which happened annually in tune with Rome’s political calendar. That regularity is going to be important to understand how this process is able to move so many people around: because it is regular, people could adapt their schedules and make provisions for a process that happened every year. I should note the dilectus could also be held out of season, though often the times we hear about this it is because it went poorly (e.g. in 275 BC, no one shows up).

The process really begins with the consular elections for the year, which bounced around a little in the calendar but generally happened around September,2 though the consuls do not take office until the start of the next calendar year. As we’ve discussed, the year originally seems to have started in March (and so consuls were inaugurated then), but in 153 was shifted to January (and so consuls were inaugurated then).

What’s really clear is that there is some standard business that happens as the year turns over every year in the Middle Republic and we can see this in the way that Livy structures his history, with year-breaks signaled by these events: the inauguration of new consuls, the assignment of senior Roman magistrates and pro-magistrates to provinces, and the determinations of how forces will be allotted between those provinces. And that sequence makes a lot of sense: once the Senate knows who has been elected, it can assign provinces to them for the coming year (the law requiring Senate province assignments to be blind to who was elected, the lex Sempronia de provinciis consularibus, was only passed in 123) and then allocate troops to them. That allocation (which also, by the by, includes redirecting food supplies from one theater to another, as Rome is often militarily actively in multiple places) includes both existing formations, but is also going to include the raising of new legions or the conscription of new troops to fill out existing legions, a practice Livy notes.

The consuls, now inaugurated have another key task before they can embark on the dilectus, which is the selection of military tribunes, a set of staff officers who assist the consuls and other magistrates leading armies. There are six military tribunes per legion (so 24 in a normal year where each consul enrolls two legions); by this point four are elected and two are appointed by the consul. The military tribunes themselves seem to have often been a mix, some of them being relatively inexperienced aristocrats doing their military service in the most prestigious way possible and getting command experience, while Polybius also notes that some military tribunes were required to have already had a decade in the ranks when selected (Polyb. 6.19.1). These fellows have to be selected first because they clearly matter for the process as it goes forward.

The end of this process, which as we’ll see takes place over several days at least, though exactly how many is unclear, will have have had to have taken place in or before March, the Roman month of Martius, which opened the normal campaigning season with a bunch of festivals on the Kalends (the first day of the month) to Mars. As Rome’s wars grew more distant and its domestic affairs more complex, it’s not surprising that the Romans opted to shift where the year began on the calendar to give the new consuls a bit more of winter to work with before they would be departing Rome with their armies. It should be noted that while Roman warfare was seasonal, it was only weakly so: Roman armies stayed deployed all year round in the Middle Republic, but serious operations generally waited until spring when forage and fodder would be more available.

That in turn also means that the dilectus is taking place in winter, which also matters for understanding the process: this is a low-ebb in the labor demands in the agricultural calendar. I find it striking that Rome’s elections happen in late summer or early fall, when it would actually be rather inconvenient for poor Romans to spend a day voting (it’s the planting season), but the dilectus is placed over winter where it would be far easier to get everyone to show up. I doubt this contrast was accidental; the Roman election system is quite intentionally designed to preference the votes of wealthier Romans in quite a few ways.

So before the dilectus begins, we have our regular sequence: the consuls are inaugurated at the beginning of the year, the Senate meets and assigns provinces and sets military priorities, including how many soldiers are to be enrolled. The Senate’s advice is not technically legally binding, but in this period is almost always obeyed. Military tribunes are selected (some by election, some by appointment) and at last the consuls can announce the day of the dilectus, conveniently now falling in the first couple of months of the year when the demand for agricultural labor is low and thus everyone, in theory, can afford to show up for the selection process.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How To Raise a Roman Army: The Dilectus“, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-16.

1. And the dictator’s master of the horse.

2. On this, see J.T. Ramsey, “The Date of the Consular Elections in 63 and the Inception of Catiline’s Conspiracy”, HSCP 110 (2019): 213-270.

March 13, 2024

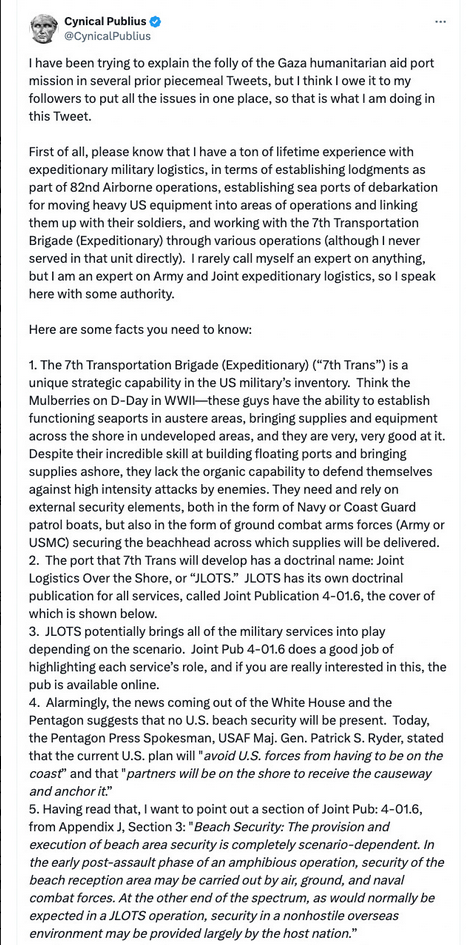

“They won’t be in Gaza, but they’ll be just offshore — a few hundred yards from Gaza”

Apparently a bunch of former military types are getting their collective panties in a bunch just because Biden is sending part of a highly specialized US Army support brigade to install a temporary offshore unloading facility to get “humanitarian aid” in to Hamas fighters the civilian population of Gaza. All the political advisors to the President want to assure everyone that there will be no “boots on the ground”, so there’s no real risk …

The Pentagon has said something that should make us all sit up and pay attention.

Quick background first:

Elements of the US Army’s 7th Transportation Brigade are on the way to Gaza. […] They won’t be in Gaza, but they’ll be just offshore — a few hundred yards from Gaza. Now read this, and take the time to read it closely. I’ll split it into two screencaps to get it all in, which will be awkward to look at, but you can just click on the link to see it all whole (and subscribe to keep up with “Cynical Publius” as all of this develops):

The extremely important part of all of that is that transportation troops aren’t combat arms troops; they’re armed for some degree of self-protection, but “they lack the organic ability to defend themselves against high-intensity attacks by enemies.” In a hostile environment, they need to be screened: they need to be protected by combat-focused forces, both on-shore and off. They need infantry in front of them, warships behind them, and aircraft overhead.

Now, via this account, look at this transcript of an … interesting Pentagon press briefing on March 8, in which a major general talks at length about the security plan for the 7th Transportation Brigade when it gets to Gaza. Sample exchange:

Q: (Inaudible) partner nations on the ground, but you’re talking about operational security, you can’t discuss what will be (inaudible).

GEN. RYDER: Right. I mean, we will — these forces will have the capability to provide some organic security. I’m just not going to get into the specifics of that.

But they don’t — or they do, but the capability of transportation troops, from a combat service support branch, is extremely limited. Again, these are not combat arms troops, and aren’t armed or trained as combat arms troops. Talking about their organic security capability is an interesting choice.

March 12, 2024

A JLOTS for Gaza?

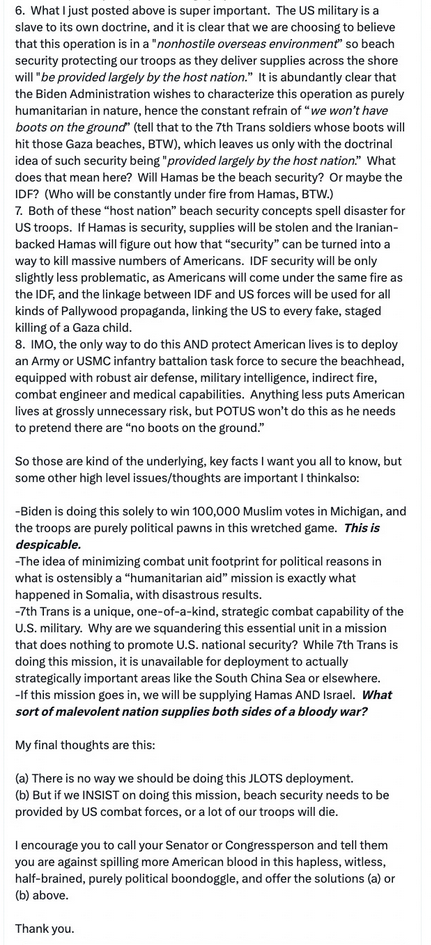

The Biden administration has made a decision to create a temporary shore unloading facility to provide Gaza with “humanitarian aid”. The particular installation is called an Army Joint Logistics Over-the-Shore (JLOTS) and will be delivered by a US Army logistics ship, USAV General Frank S. Besson (LSV-1) which was reported as departing a base in Virginia and will arrive as soon as its 12-knot top speed will allow. CDR Salamander has the details:

… and yes my friends — the Army has its own navy. Let’s take a quick look at the Besson.

Yep’r, that 243 foot, 4,200 ton ship is commanded by … a Warrant Officer. Discuss amongst yourselves.

If you’re wondering what she looks like putting a JLOTS in place;

This will take about 1,000 personnel to accomplish. I don’t know a single maritime professional who thinks this is a good idea given the location and conditions ashore, but orders are orders. Make the best attempt you can.

An interesting note; this is not a Navy operation, but an Army operation. Remember what I told you about the fate of the East Coast Amphibious Construction Battalion TWO (ACB2) last summer? This story aligns well with the Anglosphere’s problem with seablindness we discussed on yesterday’s Midrats with James Smith.

As for my general thought on doing this? I’ll avoid the politics as much as I can, but I have concerns.

Generally speaking, no operation starts out on the right foot with a lie.

“We’re not planning for this to be an operation that would require U.S. boots on the ground,” said a senior administration official.

I’m not mad at the official. They are just making sure their statement is in line with higher direction and guidance. President Biden was clear in his SOTU speech;

The United States has been leading international efforts to get more humanitarian assistance into Gaza. Tonight, I’m directing the U.S. military to lead an emergency mission to establish a temporary pier in the Mediterranean on the coast of Gaza that can receive large shipments carrying food, water, medicine, and temporary shelters.

No U.S. boots will be on the ground.

You cannot build a pier, even JLOTS, without putting boots on the ground. Just look at the above picture again.