This is the “compare and contrast” paper, and is about as simple as they come. You take two things that aren’t exactly like each other. It’s just like Sesame Street, but with books.

Then you list 5 ways they are similar and 5 ways they are different. Voilá — you’ve written a college paper!

Ernest Hemingway and Jane Austen are both writers who share the same language: English. But Hemingway is an American who liked bullfighting and drinking martinis. Jane Austen is English and never fought a bull. She probably drank tea, because the martini wasn’t invented until 1863, some 47 years after her death …

You can write this stuff in your sleep, provided you dream about Wikipedia entries. But be forewarned: the reliable C&C probably only gets you a reliable C grade.

Ted Gioia, “The 4 Types of College papers for English Majors”, The Honest Broker, 2023-02-27.

June 2, 2023

QotD: The four types of college papers for English Majors – 1. The Reliable C&C

May 12, 2023

QotD: Great (but young) Romantic poets

History being the study of human beings and how they do, you need a baseline grasp of how humans are. It doesn’t matter how smart you are — if you don’t have a good baseline grasp of human nature, History, the discipline, will always elude you.

[This is true of any Humanity, of course. Shelley and Keats have to be in the conversation for “greatest English poet,” right up there with Shakespeare. One or both of them might’ve been more naturally talented than the Bard. But Shakespeare was clearly a man of long, deep experience, whereas the Romantics … weren’t. For every “Ozymandias” or “To a Nightingale”, there’s at least one reminder that these guys died at 29 and 25, respectively. To call “The Masque of Anarchy” sophomoric is an insult to sophomores. “Like lions after slumber, In unvanquishable number.” Ugh. Good God, y’all].

Which is why that “social construction” stuff is so popular. Yeah yeah, it has some real (though really limited) explanatory power, but mostly it’s an excuse for kids who believe themselves clever to avoid contrary evidence. Calling, say, “masculinity” “just a social construction” frees you of the burden of entering the headspace of men who do things as men, because they’re men. To stick with a theme: Shakespeare could’ve written something like “the Masque of Anarchy” — probably as a wicked bit of characterization in Hamlet: The Wittenberg Years — but Shelley never could’ve written MacBeth’s “sound and fury” soliloquy. Shakespeare had obviously seen violent death; Shelley obviously hadn’t.

Knowledge of human nature is almost nonexistent in the Biz.

Severian, “How to Teach History”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-12-23.

April 28, 2023

Field Marshal Slim’s secret vice – he also wrote articles and short stories under pseudonym

It’s no secret that I have a very high regard for Field Marshal William Slim, so I’m quite looking forward to reading some of Slim’s pre-WW2 writings that have just been gathered together by Dr. Robert Lyman in a three-volume set:

Few people during his lifetime, and even fewer now, know that the man who was to become one of the greatest British generals of all time – and I’m not exaggerating – was in fact a secret scribbler. Now, many people know that he was the author of at least two best selling books. In 1956 he wrote his account of the Burma campaign, Defeat into Victory, described by one reviewer, quite rightly in my view, as “the best general’s book of World War II”. Then, in 1959, he published, under the title of Unofficial History, a series of articles about his military experience, some of which had been published previously as articles in Blackwood’s magazine. This was the first indication that there was an unknown literary side to Slim. The fact that he was a secret scribbler, or at least had been one once, was only publicly revealed on the publication of his biography in 1976 by Ronald Lewin – Slim, The Standard Bearer – which incidentally won the W.H. Smith Literary Award that same year. Lewin explained that Slim had written material for publication long before the war. In fact, between 1931 and 1940 he wrote a total of 44 articles, extending in length between two and eight thousand words – a total of 122,000 words in all – for a range of newspapers and magazines, including Blackwood’s Magazine, the Daily Mail, the Evening Express and the Illustrated Weekly of India. According to Lewin, he did this to supplement his earnings as an officer of the Indian Army. He didn’t do it to create a name for himself as a writer, or because he had pretensions to the artistic life, but because he needed the money. As with all other officers at the time who did not have the benefit of what was described euphemistically as “private means” he struggled to live off his army salary, especially to pay school fees for his children, John (born 1927) and Una (born 1930). Accordingly, he turned his hand to writing articles under a pseudonym, mainly of Anthony Mills (Mills being Slim spelt backwards) and, in one instance, that of Judy O’Grady.

With the war over, and senior military rank attained, he never again penned stories of this kind for publication. With it died any common remembrance of his pre-war literary activities. Copies of the articles have languished ever since amidst his papers in the Churchill Archives Centre at the University of Cambridge, from where I rescued them last year. They have been republished this week by Richard Foreman of Sharpe Books.

During the time Slim was writing these the pseudonym protected him from the gaze of those in the military who might believe that serious soldiers didn’t write fiction, and certainly not for public consumption via the newspapers. He certainly went to some lengths to ensure that his military friends and colleagues did not know of this unusual extra-curricular activity. In a letter to Mr S. Jepson, editor of the Illustrated Times of India on 26 July 1939 (he was then Commanding Officer of 2/7 Gurkha Rifles in Shillong, Assam) he warned that he needed to use an additional pseudonym to the one he normally used, because that – Anthony Mills – would then be immediately “known to several people and I do not wish them to identify me also as the writer of certain articles in Blackwood’s and Home newspapers. I am supposed to be a serious soldier and I’m afraid Anthony Mills isn’t.”

What do these 44 articles tell us of Slim? He would never have pretended that his writings represented any higher form of literary art. He certainly had no pretensions to a life as a writer. He was, first and foremost, a soldier. His writing was to supplement the family’s income. But, as readers will attest, he was very good at it. They demonstrate his supreme ability with words. As Defeat into Victory was to demonstrate, he was a master of the telling phrase every bit as much as he was a master of the battlefield. He made words work. They were used simply, sparingly, directly. Nothing was wasted; all achieved their purpose.

The articles also show Slim’s propensity for storytelling. Each story has a purpose. Some were simply to provide a picture of some of the characters in his Gurkha battalion, some to tell the story of a battle or of an incident while on military operations. Some are funny, some not. Some are of an entirely different kind, and have no military context whatsoever. These are often short adventure stories, while some can best be described as morality tales. A couple of them warned his readers not to jump to conclusions about a person’s character. Some showed a romantic tendency to his nature.

The stories can be placed into three broad categories. The first comprises seventeen stories about the Indian Army, of which the Gurkha regiments formed an important part. The second group are eleven stories about India, with no or only a passing military reference. The third, much smaller group, contains seventeen stories with no Indian or military dimension.

December 30, 2022

The continued relevance of Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language”

In Quillette, George Case praises Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” (which was one of the first essays that convinced me that Orwell was one of the greatest writers of the 20th century), and shows how it still has relevance today:

George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” is widely considered one of the greatest and most influential essays ever written. First published in Britain’s Horizon in 1946, it has since been widely anthologized and is always included in any collection of the writer’s essential nonfiction. In the decades since its appearance, the article has been quoted by many commentators who invoke Orwell’s literary and moral stature in support of its continued relevance. But perhaps the language of today’s politics warrants some fresh criticisms that even the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm could not have conceived.

“Politics and the English Language” addressed the jargon, double-talk, and what we would now call “spin” that had already distorted the discourse of the mid-20th century. “In our time,” Orwell argued, “political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. … Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. … Political language — and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists — is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Those are the sentences most cited whenever a modern leader or talking head hides behind terms like “restructuring” (for layoffs), “visiting a site” (for bombing), or “alternative facts” (for falsehoods). In his essay, Orwell also cut through the careless, mechanical prose of academics and journalists who fall back on clichés — “all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally”.

These objections still hold up almost 80 years later, but historic changes in taste and technology mean that they apply to a new set of unexamined truisms and slogans regularly invoked less in oratory or print than through televised soundbites, online memes, and social media: the errors of reason and rhetoric identified in “Politics and the English Language” can be seen in familiar examples of empty platitudes, stretched metaphors, and meaningless cant which few who post, share, like, and retweet have seriously parsed. Consider how the following lexicon from 2023 is distinguished by the same question-begging, humbug, and sheer cloudy vagueness exposed by George Orwell in 1946.

[…]

Climate, [mis- and dis-]information, popular knowledge, genocide, land claims, sexual assault, and racism are all serious topics, but politicizing them with hyperbole turns them into trite catchphrases. The language cited here is largely employed as a stylistic template by the outlets who relay it — in the same way that individual publications will adhere to uniform guidelines of punctuation and capitalization, so too must they now follow directives to always write rape culture, stolen land, misinformation, or climate emergency in place of anything more neutral or accurate. Sometimes, as with cultural genocide or systemic racism, the purpose appears to be in how the diction of a few extra syllables imparts gravity to the premise being conveyed, as if a gigantic whale is a bigger animal than a whale, or a horrific murder is a worse crime than a murder.

Elsewhere, the words strive to alter the parameters of an issue so that its actual or perceived significance is amplified a little longer. “Drunk driving” will always be a danger if the legal limits of motorists’ alcohol levels are periodically lowered; likewise, relations between the sexes and a chaotic range of public opinion will always be problematic if they can be recast as rape culture, hate, or disinformation. This lingo typifies the parroted lines and reflexive responses of political communication in the 21st century.

In “Politics and the English Language”, George Orwell’s concluding lesson was not just that parroted lines and reflexive responses were aesthetically bad, or that they revealed professional incompetence in whoever crafted them, but that they served to suppress thinking. “The invasion of one’s mind by ready-made phrases … can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one’s brain”, he wrote. He is still right: glib, shallow expression reflects, and will only perpetuate, glib, shallow thought, achieving no more than to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.

December 28, 2022

QotD: Collective guilt

As for the concept of collective guilt, I personally think that it is totally unjustified to hold one person responsible for the behaviour of another person or a collective of persons. Since the end of World War Two I have not become weary of publicly arguing against the collective guilt concept. Sometimes, however, it takes a lot of didactic tricks to detach people from their supersitions. An American woman once confronted me with the reporach, “How can you still write some of your books in German, Adolf Hitler’s language?” In response, I asked her if she had knives in her kitchen, and when she answered that she did, I acted dismayed and shocked, exclaiming, “How can you still use knives after so many killers have used them to stab and murder their victims?” She stopped objecting to my writing books in German.

Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, 1946.

December 20, 2022

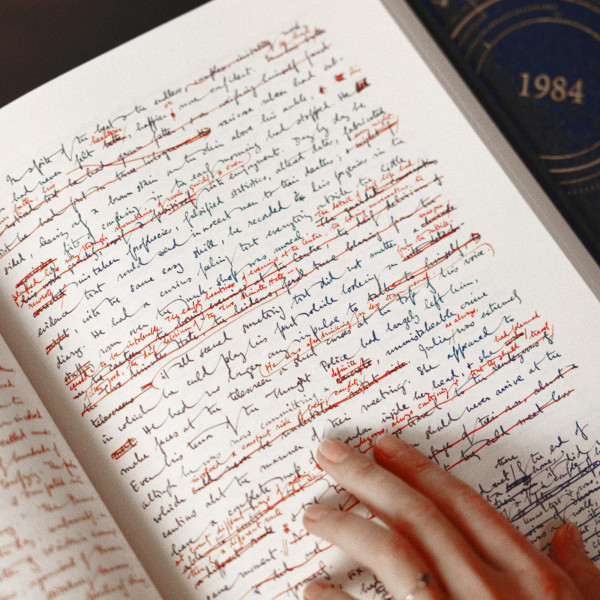

A true behind-the-scenes look at George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

In Spiked, Alexander Adams reports on a new, limited edition of the surviving portion of George Orwell’s manuscript for the novel:

A photo from SP Books’ web page showing the reproduction of Orwell’s manuscript.

SP Books, https://www.spbooks.com/150-1984-9791095457114.html

Published by SP Books, this is Nineteen Eighty-Four as you’ve never seen it before. It reproduces, in colour facsimile, the 197 surviving pages of Orwell’s manuscript, held by the John Hay Library at Brown University, Rhode Island. We see Orwell’s work in fountain pen and ballpoint (complete with ink blots), as well as 14 typewritten sides. We are even given his doodles and pen tests. Readers will remember how Winston also marvels at the beauty of the paper and binding of a blank book he buys from a junk shop.

This edition contains what amounts to 44 per cent of the text of the published novel. It is in a jumbled state, with pages missing and drastic changes made. There are many crossings out and additions. The handwriting can be a little tricky to decipher – Orwell had a habit of using cursive joining lines between words and using abbreviations. Added to that, the script can be somewhat crabbed, especially where Orwell adds text between existing lines. With a little patience, though, the reader can adjust to Orwell’s writing, especially if familiar with the text, and glimpse this most familiar of novels anew.

This version includes an introduction by Orwell scholar DJ Taylor. He tells us that although Orwell usually wrote quickly, he took five years to complete Nineteen Eighty-Four. Taylor details the difficult conditions that explain the novel’s long gestation. The death of Orwell’s first wife in 1945, the effort of raising their young son alone and the toll of tuberculosis all slowed work and drained the author’s energy (tuberculosis would kill him in 1950, only months after the novel’s publication). There are indications that Orwell let the book go to publication even though he thought it was not properly finished.

Looking at this draft, we can see Orwell revising heavily as he wrote. Some revisions are minor, such as Trotsky-figure Goldstein’s description of the workings of the Party and his description of the geopolitics of Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia. Other changes are more significant. Here, in the propaganda film described by Winston at the start of his diary, there is a graphic passage about the lynching of a pregnant black woman. Orwell seems to have cut these lines on grounds of decency. He also reduced the references to race overall, perhaps uncomfortable about the implications of speaking so generally about groups and types. Orwell’s background as a policeman in Burma no doubt made him sensitive to racial issues.

December 18, 2022

QotD: Citation systems and why they were developed

For this week’s musing I wanted to talk a bit about citation systems. In particular, you all have no doubt noticed that I generally cite modern works by the author’s name, their title and date of publication (e.g. G. Parker, The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road (1972)), but ancient works get these strange almost code-like citations (Xen. Lac. 5.3; Hdt. 7.234.2; Thuc. 5.68; etc.). And you may ask, “What gives? Why two systems?” So let’s talk about that.

The first thing that needs to be noted here is that systems of citation are for the most part a modern invention. Pre-modern authors will, of course, allude to or reference other works (although ancient Greek and Roman writers have a tendency to flex on the reader by omitting the name of the author, often just alluding to a quote of “the poet” where “the poet” is usually, but not always, Homer), but they did not generally have systems of citation as we do.

Instead most modern citation systems in use for modern books go back at most to the 1800s, though these are often standardizations of systems which might go back a bit further still. Still, the Chicago Manual of Style – the standard style guide and citation system for historians working in the United States – was first published only in 1906. Consequently its citation system is built for the facts of how modern publishing works. In particular, we publish books in codices (that is, books with pages) with numbered pages which are typically kept constant in multiple printings (including being kept constant between soft-cover and hardback versions). Consequently if you can give the book, the edition (where necessary), the publisher and a page number, any reader seeing your citation can notionally go get that edition of the book and open to the very page you were looking at and see exactly what you saw.

Of course this breaks down a little with mass-market fiction books that are often printed in multiple editions with inconsistent pagination (thus the endless frustration with trying to cite anything in A Song of Ice and Fire; the fan-made chapter-based citation system for a work without numbered or uniquely named chapters is, I must say, painfully inadequate.) but in a scholarly rather than wiki-context, one can just pick a specific edition, specify it with the facts of publication and use those page numbers.

However the systems for citing ancient works or medieval manuscripts are actually older than consistent page numbers, though they do not reach back into antiquity or even really much into the Middle Ages. As originally published, ancient works couldn’t have static page numbers – had they existed yet, which they didn’t – for a multitude of reasons: for one, being copied by hand, the pagination was likely to always be inconsistent. But for ancient works the broader problem was that while they were written in books (libri) they were not written in books (codices). The book as a physical object – pages, bound together at a spine – is more technically called a codex. After all, that’s not the only way to organize a book. Think of a modern ebook for instance: it is a book, but it isn’t a codex! Well, prior to codex becoming truly common in third and fourth centuries AD, books were typically written on scrolls (the literal meaning of libri, which later came to mean any sort of book), which notably lack pages – it is one continuous scroll of text.

Of course those scrolls do not survive. Rather, ancient works were copied onto codices during Late Antiquity or the Middle Ages and those survive. When we are lucky, several different “families” of manuscripts for a given work survive (this is useful because it means we can compare those manuscripts to detect transcription errors; alas in many cases we have only one manuscript or one clearly related family of manuscripts which all share the same errors, though such errors are generally rare and small).

With the emergence of the printing press, it became possible to print lots of copies of these works, but that combined with the manuscript tradition created its own problems: which manuscript should be the authoritative text and how ought it be divided? On the first point, the response was the slow and painstaking work of creating critical editions that incorporate the different manuscript traditions: a main text on the page meant to represent the scholar’s best guess at the correct original text with notes (called an apparatus criticus) marking where other manuscripts differ. On the second point it became necessary to impose some kind of organizing structure on these works.

The good news is that most longer classical works already had a system of larger divisions: books (libri). A long work would be too long for a single scroll and so would need to be broken into several; its quite clear from an early point that authors were aware of this and took advantage of that system of divisions to divide their works into “books” that had thematic or chronological significance. Where such a standard division didn’t exist, ancient libraries, particularly in Alexandria, had imposed them and the influence of those libraries as the standard sources for originals from which to make subsequent copies made those divisions “canon”. Because those book divisions were thus structurally important, they were preserved through the transition from scrolls to codices (as generally clearly marked chapter breaks), so that the various “books” served as “super-chapters”.

But sub-divisions were clearly necessary – a single librum is pretty long! The earliest system I am aware of for this was the addition of chapter divisions into the Vulgate – the Latin-language version of the Bible – in the 13th century. Versification – breaking the chapters down into verses – in the New Testament followed in the early 16th century (though it seems necessary to note that there were much older systems of text divisions for the Tanakh though these were not always standardized).

The same work of dividing up ancient texts began around the same time as versification for the Bible. One started by preserving the divisions already present – book divisions, but also for poetry line divisions (which could be detected metrically even if they were not actually written out in individual lines). For most poetic works, that was actually sufficient, though for collections of shorter poems it became necessary to put them in a standard order and then number them. For prose works, chapter and section divisions were imposed by modern editors. Because these divisions needed to be understandable to everyone, over time each work developed its standard set of divisions that everyone uses, codified by critical texts like the Oxford Classical Texts or the Bibliotheca Teubneriana (or “Teubners”).

Thus one cited these works not by the page numbers in modern editions, but rather by these early-modern systems of divisions. In particular a citation moves from the larger divisions to the smaller ones, separating each with a period. Thus Hdt. 7.234.2 is Herodotus, Book 7, chapter 234, section 2. In an odd quirk, it is worth noting classical citations are separated by periods, but Biblical citations are separated by colons. Thus John 3:16 but Liv. 3.16. I will note that for readers who cannot access these texts in the original language, these divisions can be a bit frustrating because they are often not reproduced in modern translations for the public (and sometimes don’t translate well, where they may split the meaning of a sentence), but I’d argue that this is just a reason for publishers to be sure to include the citation divisions in their translations.

That leaves the names of authors and their works. The classical corpus is a “closed” corpus – there is a limited number of works and new ones don’t enter very often (occasionally we find something on a papyrus or lost manuscript, but by “occasionally” I mean “about once in a lifetime”) so the full details of an author’s name are rarely necessary. I don’t need to say “Titus Livius of Patavium” because if I say Livy you know I mean Livy. And in citation as in all publishing, there is a desire for maximum brevity, so given a relatively small number of known authors it was perhaps inevitable that we’d end up abbreviating all of their names. Standard abbreviations are helpful here too, because the languages we use today grew up with these author’s names and so many of them have different forms in different languages. For instance, in English we call Titus Livius “Livy” but in French they say Tite-Live, Spanish says Tito Livio (as does Italian) and the Germans say Livius. These days the most common standard abbreviation set used in English are those settled on by the Oxford Classical Dictionary; I am dreadfully inconsistent on here but I try to stick to those. The OCD says “Livy”, by the by, but “Liv.” is also a very common short-form of his name you’ll see in citations, particularly because it abbreviates all of the linguistic variations on his name.

And then there is one final complication: titles. Ancient written works rarely include big obvious titles on the front of them and often were known by informal rather than formal titles. Consequently when standardized titles for these works formed (often being systematized during the printing-press era just like the section divisions) they tended to be in Latin, even when the works were in Greek. Thus most works have common abbreviations for titles too (again the OCD is the standard list) which typically abbreviate their Latin titles, even for works not originally in Latin.

And now you know! And you can use the link above to the OCD to decode classical citations you see.

One final note here: manuscripts. Manuscripts themselves are cited by an entirely different system because providence made every part of paleography to punish paleographers for their sins. A manuscript codex consists of folia – individual leaves of parchment (so two “pages” in modern numbering on either side of the same physical page) – which are numbered. Then each folium is divided into recto and verso – front and back. Thus a manuscript is going to be cited by its catalog entry wherever it is kept (each one will have its own system, they are not standardized) followed by the folium (‘f.’) and either recto (r) or verso (v). Typically the abbreviation “MS” leads the catalog entry to indicate a manuscript. Thus this picture of two men fighting is MS Thott.290.2º f.87r (it’s in Det Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen):

MS Thott.290.2º f.87r which can also be found on the inexplicably well maintained Wiktenauer; seriously every type of history should have as dedicated an enthusiast community as arms and armor history.

And there you go.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, June 10, 2022”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-06-10.

November 27, 2022

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

In Quillette, Robin Ashenden discusses the life experiences of Aleksandr Slozhenitsyn that informed the novel that made him famous:

The book was published less than 10 years after the death of Joseph Stalin, the dictator who had frozen his country in fear for nearly three decades and subjected his people to widespread deportation, imprisonment, and death. His successor Nikita Khrushchev — a man who, by his own admission, came to the job “elbow deep in blood” — had set out on a redemptive mission to liberalise the country. The Gulags had been opened and a swathe of prisoners freed; Khrushchev had denounced his predecessor publicly as a tyrant and a criminal and, at the 22nd Party Congress in October 1961, a full programme of de-Stalinisation had been announced. As for the Arts, previously neutered by the Kremlin’s policy of “Socialist Realism” — in which the values of Communism had to be resoundingly affirmed — they too were changing. Now, a new openness and a new realism was called for by Khrushchev’s supporters: books must tell the truth, even the uncomfortable truth about Communist reality … up to a point. That this point advanced or retreated as Khrushchev’s power ebbed and flowed was something no writer or publisher could afford to miss.

Solzhenitsyn’s book told the story of a single day in the 10-year prison-camp sentence of a Gulag inmate (or zek) named Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. Following decades of silence about Stalin’s prison-camp system and the innocent citizens languishing within it, the book’s appearance seemed to make the ground shake and fissure beneath people’s feet. “My face was smothered in tears,” one woman wrote to the author after she read it. “I didn’t wipe them away or feel ashamed because all this, packed into a small number of pages … was mine, intimately mine, mine for every day of the fifteen years I spent in the camps.” Another compared his book to an “atomic bomb”. For such a slender volume — about 180 pages — the seismic wave it created was a freak event.

As was the story of its publication. By the time it came out, there was virtually no trauma its author — a 44-year-old married maths teacher working in the provincial city of Ryazan — had not survived. After a youth spent in Rostov during the High Terror of Stalin’s 1930s, Solzhenitsyn had gone on to serve eagerly in the Red Army at the East Prussian front, before disaster struck in 1945. Arrested for some ill-considered words about Stalin in a letter to a friend, he was handed an eight-year Gulag sentence. In 1953, he was sent into Central Asian exile, only to be diagnosed with cancer and given three weeks to live. After a miraculous recovery, he vowed to dedicate this “second life” to a higher purpose. His writing, honed in the camps, now took on the ruthless character of a holy mission. In this, he was fortified by the Russian Orthodox faith he’d rediscovered during his sentence, and which had replaced his once-beloved, now abandoned Marxism.

Solzhenitsyn had, since his youth, wanted to make his mark as a Russian writer. In the Gulag, he’d written cantos of poetry in his head, memorized with the help of matchsticks and rosary beads to hide it from the authorities. During his Uzbekistan exile, he’d follow a full day’s work with hours of secret nocturnal writing about the darker realities of Soviet life, burying his tightly rolled manuscripts in a champagne bottle in the garden. Later, reunited with the wife he’d married before the war, he warned her to expect no more than an hour of his company a day — “I must not swerve from my purpose.” No friendships — especially close ones — were allowed to develop with his fellow Ryazan teachers, lest they take up valuable writing time, discover his perilous obsession, or blow his cover. Subterfuge became second nature: “The pig that keeps its head down grubs up the tastiest root.” Yet throughout it all, he was sceptical that his work would ever be available to the general public: “Publication in my lifetime I must put out of my mind.”

After the 22nd Party Congress, however, Solzhenitsyn recognised that the circumstances were at last propitious, if all too fleeting. “I read and reread those speeches,” he wrote later, “and the walls of my secret world swayed like curtains in the theatre … had it arrived, then, the long-awaited moment of terrible joy, the moment when my head must break water?” It seemed that it had. He got out one of his eccentric-looking manuscripts — double-sided, typed without margins, and showing all the signs of its concealment — and sent it to the literary journal of his choice. That publication was the widely read, epoch-making Novy Mir (“New World”), a magazine whose progressive staff hoped to drag society away from Stalinism. They had kept up a steady backwards-forwards dance with the Khrushchev regime throughout the 1950s, invigorated by the thought that each new issue might be their last.

October 4, 2022

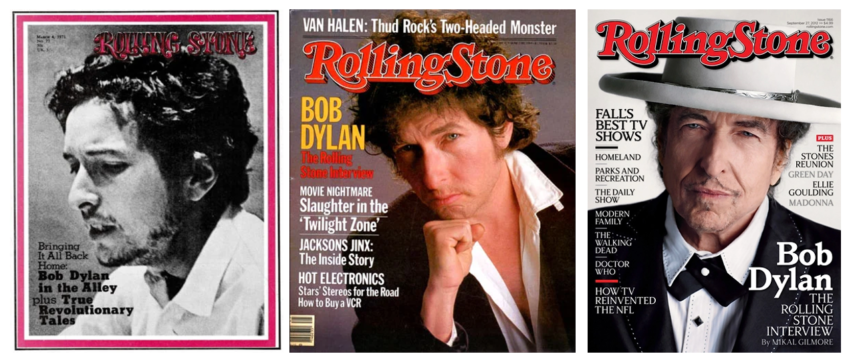

“On the cover of the Rolling Stone“

Ted Gioia discusses the oddly nostalgic turn modern music writing has taken:

The first thing you notice is the sheer abundance of music magazines on display. We must truly be living in a golden age of music writing if it can support so many periodicals.

I was very happy to see this — at least at first glance.

But at second glance, I started to notice the cover stories.

Lavish attention is devoted here to artists who built their audience in the last century — Miles Davis, David Bowie, Buddy Holly, Blondie, Led Zeppelin, Björk, Motorhead, The Cure, etc. That’s an impressive roster of artists (well, most of them), but they don’t really need the publicity nowadays — they were legends before many of us were born.

Even the magazine names reveal a tilt toward nostalgia. I can’t make out the titles in their entirety, but I see the words Retro, Vintage, and Classic. Publishers are shrewd people, and they don’t put these words in large font unless the audience responds to them.

Maybe print media is nostalgic by definition — if, as we’re repeatedly told, young people don’t read things on paper. (I’m skeptical of that claim, but I hear it all the time.) Yet when I visit the websites, I see the same backward glance. You can’t click on Rolling Stone‘s homepage or Twitter feed without finding some massive list article — touting the “100 Best Songs of 1982” or “The 100 Greatest Country Albums of All Time“. You will find similar retro celebrations at almost every other music media website with a large crossover readership.

Editors love lists nowadays, especially of all-time greats. If I pitch an article like that, the whole editorial team starts salivating — you can even feel the moisture over Zoom — in sharp contrast to any proposed article on a young, unproven musician. Those pitches get pitched right back in your face. You might conclude that we have now arrived at the end of history, with all greatness residing in the past. The editors, at least, must think so.

Things weren’t always like this. Go back and look at old issues of Rolling Stone or Downbeat or some other music magazine — there were years in which every cover story was about a living person and usually someone young with something new to say.

Those days are gone. But here’s the most ironic fact of all — the actual cover stories haven’t changed.

By the way, I’d like to know when Rolling Stone published its first “all-time greats” list — that was the moment when nostalgia first entered the rock bloodstream, a vital force previously resistant to sentimental yearnings for the past.

September 29, 2022

Nostradamus

In the latest post at Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander considers prophecy “From Nostradamus to Fukuyama”. Here’s the section on Nostradamus (because I don’t have a lot of time for Fukuyama, you’ll have to read the rest at ACX):

“House of Nostradamus in Salon, France. Now a museum.” by photographymontreal is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0 .

Nostradamus was a 16th century French physician who claimed to be able to see the future.

(never trust doctors who dabble in futurology, that’s my advice)

His method was: read books of other people’s prophecies and calculate some astrological charts, until he felt like he had a pretty good idea what would happen in the future. Then write it down in the form of obscure allusions and multilingual semi-gibberish, to placate religious authorities (who apparently hated prophecies, but loved prophecies phrased as obscure allusions and multilingual semi-gibberish).

In 1559, he got his big break. During a jousting match, a count killed King Henry II of France with a lance through the visor of his helmet. Years earlier, Nostradamus had written:

The young lion will overcome the older one,

On the field of combat in a single battle;

He will pierce his eyes through a golden cage,

Two wounds made one, then he dies a cruel deathThe nobleman was a bit younger than the king, supposedly they both had lions on their shield (false), maybe King Henry was wearing a golden helmet (I can’t find evidence for this, but as a consolation prize please accept this picture of his amazing parade armor), and his slow agonizing death over ten days from his wounds was pretty cruel. Seems like a match, sort of. Anyway, for the next five hundred years lots of people were really into Nostradamus and spent goodness knows how many brain cycles trying to interpret his incomprehensible quatrains.

The basic Nostradamic method was:

Write 942 vague and incomprehensible quatrains, out of order and without any dates.

Whenever something happens, say “that sounds a lot like quatrain #143!” or “quatrain #558 predicted that”

Prophet

For example, prophecy 106:

Near the gates and within two cities

There will be two scourges the like of which was never seen,

Famine within plague, people put out by steel,

Crying to the great immortal God for reliefThis is an okay match for the atomic bombs, in the sense that there were two cities where something really bad happened. But read on to prophecy 107:

Amongst several transported to the isles,

One to be born with two teeth in his mouth

They will die of famine the trees stripped,

For them a new King issues a new edict.… and it starts to sound like he’s just kind of saying random stuff and some of it’s sticking by sheer luck.

A few prophecies sound more impressive than this, eg:

The lost thing is discovered, hidden for many centuries.

Pasteur will be celebrated almost as a god-like figure.

This is when the moon completes her great cycle,

but by other rumours he shall be dishonouredThis seems to name Pasteur, who was indeed a celebrated discoverer of things. And Nostradamus scholars note that a historian accused Pasteur of plagiarism in 1995, which is a kind of dishonorable rumor. But the work here is being done by the translator: Pasteur is just French for “pastor”, and an honest translation would have just said “the pastor will be celebrated …”, which is in tune with all his other vague allusions to things happening.

The blood of the just will be demanded of London

Burnt by fire in the year ’66

The ancient Lady will fall from her high place

And many of the same sect will be killed.Seems like a match for the London fire of 1666. But again checking the original French and the commentators, the second line is more properly “burnt by fire in 23 the 6”, which a fanciful translator rounded off to 20 * 3 + 6 = 66 and then assumed was a year. The experts say that this is really a coded reference to 23 Protestants being burned, in groups of six, during Nostradamus’ lifetime (many of his quatrains are references to past or present events, for some reason). This sounds more compatible with the “many of the same sect will be killed” ending.

I had a weird experience writing the end of this first part of the post. When I was a kid, reading through my parents’ old books, I came across an weird almanac from the 70s that had a section on Nostradamus. It listed some of his most famous prophecies, including the ones above, but also (reconstructing from memory and probably getting some things wrong, sorry):

The way of life according to Thomas More

Will give way to another more sweet and seductive

In the land of cold winds that first gave it birth

Without strife, without a war it will fall… and the 70s almanac interpreted this as meaning Soviet communism would fall peacefully. Reading this in 1995 or whenever it was I read it, a few years after Soviet communism did fall peacefully, I was really impressed: this is the only example I know where someone used a Nostradamus quatrain to predict something before it happened.

But I searched for the exact text so I could include the correct version in this essay, and I didn’t find it — this is none of Nostradamus’ 942 prophecies! The almanac authors must have made it up, or unwittingly copied it from someone else who did.

But I remember this very clearly — the almanac was from 1970-something. So how did the faker know Russian communism would collapse?

The moral of the story is: just because Nostradamus wasn’t a real prophet, doesn’t mean nobody else is.

September 25, 2022

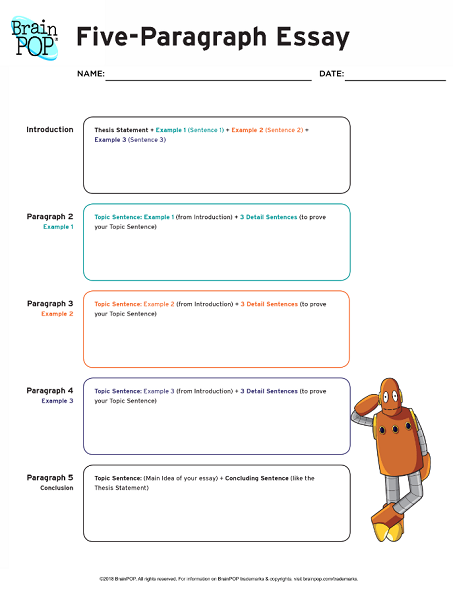

The five-paragraph essay straitjacket

In Aeon, David Labaree discusses the good intent and terrible results of forcing students to rigidly follow the “five paragraph” model of essay writing:

Schools and colleges in the United States are adept at teaching students how to write by the numbers. The idea is to make writing easy by eliminating the messy part – making meaning – and focusing effort on reproducing a formal structure. As a result, the act of writing turns from moulding a lump of clay into a unique form to filling a set of jars that are already fired. Not only are the jars unyielding to the touch, but even their number and order are fixed. There are five of them, which, according to the recipe, need to be filled in precise order. Don’t stir. Repeat.

So let’s explore the form and function of this model of writing, considering both the functions it serves and the damage it does. I trace its roots to a series of formalisms that dominate US education at all levels. The foundation is the five-paragraph essay, a form that is chillingly familiar to anyone who has attended high school in the US. In college, the model expands into the five-section research paper. Then in graduate school comes the five-chapter doctoral dissertation. Same jars, same order. By the time the doctoral student becomes a professor, the pattern is set. The Rule of Five is thoroughly fixed in muscle memory, and the scholar is on track to produce a string of journal articles that follow from it. Then it’s time to pass the model on to the next generation. The cycle continues.

Edward M White is one participant in the cycle who decided to fight back. It was the summer of 2007, and he was on the plane home from an ordeal that would have crushed a man with a less robust constitution. An English professor, he had been grading hundreds of five-paragraph essays drawn from the 280,000 that had been submitted that June as part of the Advanced Placement Test in English language and composition. In revenge, he wrote his own five-paragraph essay about the five-paragraph essay, whose fourth paragraph reads:

The last reason to write this way is the most important. Once you have it down, you can use it for practically anything. Does God exist? Well you can say yes and give three reasons, or no and give three different reasons. It doesn’t really matter. You’re sure to get a good grade whatever you pick to put into the formula. And that’s the real reason for education, to get those good grades without thinking too much and using up too much time.

White’s essay – “My Five-Paragraph-Theme Theme” – became an instant classic. True to the form, he lays out the whole story in his opening paragraph:

Since the beginning of time, some college teachers have mocked the five-paragraph theme. But I intend to show that they have been mistaken. There are three reasons why I always write five-paragraph themes. First, it gives me an organisational scheme: an introduction (like this one) setting out three subtopics, three paragraphs for my three subtopics, and a concluding paragraph reminding you what I have said, in case you weren’t paying attention. Second, it focuses my topic, so I don’t just go on and on when I don’t have anything much to say. Three and only three subtopics force me to think in a limited way. And third, it lets me write pretty much the same essay on anything at all. So I do pretty well on essay tests. A lot of teachers actually like the five-paragraph theme as much as I do.

Note the classic elements of the model. The focus on form: content is optional. The comfortingly repetitive structure: here’s what I’m going to say, here I am saying it, and here’s what I just said. The utility for everyone involved: expectations are so clear and so low that every writer can meet them, which means that both teachers and students can succeed without breaking a sweat – a win-win situation if ever there was one. The only thing missing is meaning.

For students who need a little more structure in dealing with the middle three paragraphs that make up what instructors call the “body” of the essay, some helpful tips are available – all couched in the same generic form that could be applicable to anything. According to one online document by a high-school English teacher:

The first paragraph of the body should contain the strongest argument, most significant example, cleverest illustration, or an obvious beginning point. The first sentence of this paragraph should include the “reverse hook” which ties in with the transitional hook at the end of the introductory paragraph. The topic for this paragraph should be in the first or second sentence. This topic should relate to the thesis statement in the introductory paragraph. The last sentence in this paragraph should include a transitional hook to tie into the second paragraph of the body.

You probably won’t be surprised that the second paragraph “should contain the second strongest argument, second most significant example, second cleverest illustration, or obvious follow-up to the first paragraph …” And that the third paragraph “should contain the third strongest argument …” Well, you get the picture.

September 13, 2022

QotD: J.R.R. Tolkien’s childhood and schooling

One reason highbrow people dislike The Lord of the Rings is that it is so backward-looking. But it could never have been otherwise. For good personal reasons, Tolkien was a fundamentally backward-looking person. He was born to English parents in the Orange Free State in 1892, but was taken back to the village of Sarehole, north Worcestershire, by his mother when he was three. His father was meant to join them later, but was killed by rheumatic fever before he boarded ship.

For a time, the fatherless Tolkien enjoyed a happy childhood, devouring children’s classics and exploring the local countryside. But in 1904 his mother died of diabetes, leaving the 12-year-old an orphan. Now he and his brother went to live with an aunt in Edgbaston, near what is now Birmingham’s Five Ways roundabout. In effect, he had moved from the city’s rural fringes to its industrial heart: when he looked out of the window, he saw not trees and hills, but “almost unbroken rooftops with the factory chimneys beyond”. No wonder that from the moment he put pen to paper, his fiction was dominated by a heartfelt nostalgia.

Nostalgia was in the air anyway in the 1890s and 1900s, part of a wider reaction against industrial, urban, capitalist modernity. As a boy, Tolkien was addicted to the imperial adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, and it’s easy to see The Lord of the Rings as a belated Boy’s Own adventure. An even bigger influence, though, was that Victorian one-man industry, William Morris, inspiration for generations of wallpaper salesmen. Tolkien first read him at King Edward’s, the Birmingham boys’ school that had previously educated Morris’s friend Edward Burne-Jones. And what Tolkien and his friends adored in Morris was the same thing you see in Burne-Jones’s paintings: a fantasy of a lost medieval paradise, a world of chivalry and romance that threw the harsh realities of industrial Britain into stark relief.

It was through Morris that Tolkien first encountered the Icelandic sagas, which the Victorian textile-fancier had adapted into an epic poem in 1876. And while other boys grew out of their obsession with the legends of the North, Tolkien’s fascination only deepened. After going up to Oxford in 1911, he began writing his own version of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. When his college, Exeter, awarded him a prize, he spent the money on a pile of Morris books, such as the proto-fantasy novel The House of the Wolfings and his translation of the Icelandic Volsunga Saga. And for the rest of his life, Tolkien wrote in a style heavily influenced by Morris, deliberately imitating the vocabulary and rhythms of the medieval epic.

Dominic Sandbrook, “This is Tolkien’s world”, UnHerd.com, 2021-12-10.

September 12, 2022

QotD: On the nature of our evidence of the ancient world

As folks are generally aware, the amount of historical evidence available to historians decreases the further back you go in history. This has a real impact on how historians are trained; my go-to metaphor in explaining this to students is that a historian of the modern world has to learn how to sip from a firehose of evidence, while the historian of the ancient world must learn how to find water in the desert. That decline in the amount of evidence as one goes backwards in history is not even or uniform; it is distorted by accidents of preservation, particularly of written records. In a real sense, we often mark the beginning of “history” (as compared to pre-history) with the invention or arrival of writing in an area, and this is no accident.

So let’s take a look at the sort of sources an ancient historian has to work with and what their limits are and what that means for what it is possible to know and what must be merely guessed.

The most important body of sources are what we term literary sources, which is to say long-form written texts. While rarely these sorts of texts survive on tablets or preserved papyrus, for most of the ancient world these texts survive because they were laboriously copied over the centuries. As an aside, it is common for students to fault this or that later society (mostly medieval Europe) for failing to copy this or that work, but given the vast labor and expense of copying and preserving ancient literature, it is better to be glad that we have any of it at all (as we’ll see, the evidence situation for societies that did not benefit from such copying and preservation is much worse!).

The big problem with literary evidence is that for the most part, for most ancient societies, it represents a closed corpus: we have about as much of it as we ever will. And what we have isn’t much. The entire corpus of Greek and Latin literature fits in just 523 small volumes. You may find various pictures of libraries and even individuals showing off, for instance, their complete set of Loebs on just a few bookshelves, which represents nearly the entire corpus of ancient Greek and Latin literature (including facing English translation!). While every so often a new papyrus find might add a couple of fragments or very rarely a significant chunk to this corpus, such additions are very rare. The last really full work (although it has gaps) to be added to the canon was Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia (“Constitution of the Athenians”) discovered on papyrus in 1879 (other smaller but still important finds, like fragments of Sappho, have turned up as recently as the last decade, but these are often very short fragments).

In practice that means that, if you have a research question, the literary corpus is what it is. You are not likely to benefit from a new fragment or other text “turning up” to help you. The tricky thing is, for a lot of research questions, it is in essence literary evidence or bust. […] for a lot of the things people want to know, our other forms of evidence just aren’t very good at filling in the gaps. Most information about discrete events – battles, wars, individual biographies – are (with some exceptions) literary-or-bust. Likewise, charting complex political systems generally requires literary evidence, as does understanding the philosophy or social values of past societies.

Now in a lot of cases, these are topics where, if you have literary evidence, then you can supplement that evidence with other forms […], but if you do not have the literary evidence, the other kinds of evidence often become difficult or impossible to interpret. And since we’re not getting new texts generally, if it isn’t there, it isn’t there. This is why I keep stressing in posts how difficult it can be to talk about topics that our (mostly elite male) authors didn’t care about; if they didn’t write it down, for the most part, we don’t have it.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: March 26, 2021 (On the Nature of Ancient Evidence”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-26.

August 21, 2022

David McCullough, RIP

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte remembers the late David McCullough:

David McCullough speaking at Emory University, 25 April, 2007.

Photo by Brett Weinstein via Wikimedia Commons.

David McCullough died August 7 at the age of 89. He won Pulitzer Prizes for his biographies of John Adams and Harry Truman, National Book Awards for The Path Between the Seas, about the building of the Panama Canal, and Mornings on Horseback, a biography of young Theodore Roosevelt, as well as two Francis Parkman prizes (The Path, Truman) and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He also enjoyed a prominent career as a broadcaster and several of his books were transformed into important television events, most notably HBO’s John Adams.

I read him closely over the years. Studied him, even. After finishing his major biographies — books that can’t fail to impress for their prodigious research and literary grace — I went back to his early work to trace how long it took him to develop into a master of narrative historical writing. I started at the beginning, The Johnstown Flood (1968), and was stunned to find that he was all there from page one. He had total command of his material and his story at the outset.

I wouldn’t call him a favorite writer. McCullough tended to play safe. He had a somewhat rosy view of American history: “I want to bring to life the best that can be found in the story of why we are the way we are and how we got to where we are.” He was so busy bringing the best to life that he seldom challenged his readers with the worst: truly repellant individuals or unredeemed national failure.

His subjects tended to be public-spirited men of noble character and hard-earned wisdom. He felt comfortable in their company. “It’s like picking a roommate,” he once said, explaining why he dropped the idea of a biography of Pablo Picasso. “After all, you’re going to be with that person every day, maybe for years, and why subject yourself to someone you have no respect for or outright don’t like?”

When the abhorrent forced its way into his stories, he tended to rationalize it. His formulation that Harry Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan, killing hundreds of thousands of civilians, was a lesser evil necessary to prevent a greater evil (heavy American troop losses) may have got it exactly backward.

His paeans to American greatness even wore on American audiences in his later years. Reviews of The Pioneers, his 2019 account of the Euro-American settlement of the Ohio River valley, accused him of “romanticizing white settlement and downplaying the pain inflicted on Native Americans.”

I raise these issues not to speak ill of the dead but to say that McCullough is worth reading, and reading again, even if, like me, you’re part of the minority who can find him hard to take at times. (The majority love him: I’m not sure any historian has sold more books.)

I had the pleasure of meeting David McCullough in Toronto at an intimate lunch arranged by his publisher, Simon & Schuster. I interviewed him later for Macleans. He was a complete gentleman and an enjoyable companion, notwithstanding his many twice- and thrice-told stories (an occupational hazard for touring writers).

I was able to draw him out on various aspects of non-fiction craft, which he spoke well on. What follows are some of my favorite quotes from the interview along with several other things McCullough said about writing and one comment by another author, the great Candace Millard, about his work.

August 9, 2022

QotD: Fusty old literary archaism

For as long as I can remember, readers have been trained to associate literary archaism with the stuffy and Victorian. Shielded thus, they may not realize that they are learning to avoid a whole dimension of poetry and play in language. Poets, and all other imaginative writers, have been consciously employing archaisms in English, and I should think all other languages, going back at least to Hesiod and Homer. The King James Version was loaded with archaisms, even for its day; Shakespeare uses them not only evocatively in his Histories, but everywhere for colour, and in juxtaposition with his neologisms to increase the shock.

In fairy tales, this “once upon a time” has always delighted children. Novelists, and especially historical novelists, need archaic means to apprise readers of location, in their passage-making through time. Archaisms may paradoxically subvert anachronism, by constantly yet subtly reminding the reader that he is a long way from home.

Get over this adolescent prejudice against archaism, and an ocean of literary experience opens to you. Among other things, you will learn to distinguish one kind of archaism from another, as one kind of sea from another should be recognized by a yachtsman.

But more: a particular style of language is among the means by which an accomplished novelist breaks the reader in. There are many other ways: for instance by showering us with proper nouns through the opening pages, to slow us down, and make us work on the family trees, or mentally squint over local geography. I would almost say that the first thirty pages of any good novel will be devoted to shaking off unwanted readers; or if they continue, beating them into shape. We are on a voyage, and the sooner the passengers get their sea legs, the better life will be all round.

David Warren, “Kristin Lavransdatter”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-03-21.