… there is a certain level of pride that attaches to being ignorant of those one considers his inferiors. After all, it’s the natural duty of the simple shopkeeper to know the names of the Great Lords, but it is not the duty of the Great Lords to know the names of the shopkeepers. In fact, it’s the Great Lords’ class obligation to go out of their way not to know the names of the shopkeepers, because this Duty to Know flows in one direction — upwards — and hence ignorance of one’s lessers tends to solidify and reify the assumptions of certain castes being superior to others. It makes certain that everyone understands who’s important, and who’s not.

(I know, I sound like a communist — I can’t help it. I have to agree with Dennis the Peasant — “I mean, class is what it’s all about.” I guess I would say I’m agreeing with the communist critique of the rigid reification of class structures, but I happen to think the communists and their pink fellow travelers have largely captured the upper classes. I guess by my theory they’re so good at this because they’ve spent so long plotting vengeance for the exact same slights (which they largely imagined). In a similar way they’ve gotten quite good at blacklisting and guilt-by-association, eh?)

At any rate, it is your duty to know the values and customs of living of Piers Morgan, but due to his high station (ahem) he is proudly ignorant of yours. As is so often the case in our increasingly dysfunctional and nasty politics — in which certain parties refuse to even admit that their opponents are free citizens entitled to have beliefs at all — the Out-Classes are deemed all-but-officially Beneath Notice.

Michael Totten has written a crackerjack piece — or at least I think it is — about this principle in action among our foreign policy sages, the internationalist “elite.” He detects the exact same sort of phenomenon going on when the International “elite” visit foreign nations — because anyone who doesn’t share 90% of their cultural values (and the wealth that permits/encourages these values — the International Elite is not middle-class!) is beneath notice and not worth knowing about, they don’t bother asking anyone but the 3% of the population which largely shares their beliefs and cultural inputs about their intentions and their political agenda.

Which means, in Egypt, they only ask the jet-setting wealthy Westernized elite about the prognosis for Egyptian democracy. And in Lebanon, they only ask the educated, urbane population of Beirut about their desires for the country.

And they ignore all the “Dirty People,” the low people who aren’t worth networking with and probably wouldn’t be any fun to have a sexual affair with. Unfortunately — and this has huge consequences for American foreign policy — it turns out those Dirty Poor People greatly, greatly outnumber the small coteries of educated elites that cluster in every capital country.

And so our “elites” — and honestly, we need to start looking for a more accurate discriptor — come back with completely-wrong information about foreign countries.

Why, as Totten says (changing the words a bit), “All of these Egyptians are swell, educated, moderate, sexually-loose cosmopolitans! Why, democracy has a smashing chance of working out here!”

Yeah, not so much. Not so much.

Ace, “The Unburstable Bubble of Willful Ignorance of the International Self-Purported Elites”, Ace of Spades H.Q., 2013-01-09.

April 20, 2019

QotD: They used to be called the Jet Set, but now they’re the Transnational Elite

April 12, 2019

QotD: Money is not wealth

If you want to create wealth, it will help to understand what it is. Wealth is not the same thing as money.* Wealth is as old as human history. Far older, in fact; ants have wealth. Money is a comparatively recent invention.

Wealth is the fundamental thing. Wealth is stuff we want: food, clothes, houses, cars, gadgets, travel to interesting places, and so on. You can have wealth without having money. If you had a magic machine that could on command make you a car or cook you dinner or do your laundry, or do anything else you wanted, you wouldn’t need money. Whereas if you were in the middle of Antarctica, where there is nothing to buy, it wouldn’t matter how much money you had.

Wealth is what you want, not money. But if wealth is the important thing, why does everyone talk about making money? It is a kind of shorthand: money is a way of moving wealth, and in practice they are usually interchangeable. But they are not the same thing, and unless you plan to get rich by counterfeiting, talking about making money can make it harder to understand how to make money.

Money is a side effect of specialization. In a specialized society, most of the things you need, you can’t make for yourself. If you want a potato or a pencil or a place to live, you have to get it from someone else.

How do you get the person who grows the potatoes to give you some? By giving him something he wants in return. But you can’t get very far by trading things directly with the people who need them. If you make violins, and none of the local farmers wants one, how will you eat?

The solution societies find, as they get more specialized, is to make the trade into a two-step process. Instead of trading violins directly for potatoes, you trade violins for, say, silver, which you can then trade again for anything else you need. The intermediate stuff — the medium of exchange — can be anything that’s rare and portable. Historically metals have been the most common, but recently we’ve been using a medium of exchange, called the dollar, that doesn’t physically exist. It works as a medium of exchange, however, because its rarity is guaranteed by the U.S. Government.

The advantage of a medium of exchange is that it makes trade work. The disadvantage is that it tends to obscure what trade really means. People think that what a business does is make money. But money is just the intermediate stage — just a shorthand — for whatever people want. What most businesses really do is make wealth. They do something people want.**

* Until recently even governments sometimes didn’t grasp the distinction between money and wealth. Adam Smith (Wealth of Nations, v:i) mentions several that tried to preserve their “wealth” by forbidding the export of gold or silver. But having more of the medium of exchange would not make a country richer; if you have more money chasing the same amount of material wealth, the only result is higher prices.

** There are many senses of the word “wealth,” not all of them material. I’m not trying to make a deep philosophical point here about which is the true kind. I’m writing about one specific, rather technical sense of the word “wealth.” What people will give you money for. This is an interesting sort of wealth to study, because it is the kind that prevents you from starving. And what people will give you money for depends on them, not you.

When you’re starting a business, it’s easy to slide into thinking that customers want what you do. During the Internet Bubble I talked to a woman who, because she liked the outdoors, was starting an “outdoor portal.” You know what kind of business you should start if you like the outdoors? One to recover data from crashed hard disks.

What’s the connection? None at all. Which is precisely my point. If you want to create wealth (in the narrow technical sense of not starving) then you should be especially skeptical about any plan that centers on things you like doing. That is where your idea of what’s valuable is least likely to coincide with other people’s.

Paul Graham, “How to Make Wealth”, Paul Graham, 2004-04.

February 18, 2019

Mis-measuring inequality

Tim Worstall explains why any protest in a western country about “inequality” is probably bogus from the get-go:

Their opening line, their justification:

We live in an age of astonishing inequality.

No, we don’t. We live in an age of astonishing and increasing equality. Thus any set of policies, any series of analysis, that flows from this misunderstanding of reality is going to be wrong.

And that’s all we really need to know about it all.

The problem is that their measurements – the ones they’re paying attention to – of inequality just aren’t the useful ones, the ones we’re interested in. They’re usually pre-tax, pre-benefits. They’re always pre-government supplied services. And they never, ever, look at the thing we’re actually interested in, inequality of living standards.

To give an example, the Trades Union Congress did a calculation a few years back looking at top 10% households in the UK and bottom 10%. They took the average of each decile – so, the average of the top 10% households, the average of the bottom. Then they looked at the ratio between them.

The top 10% gain some 12 times the market income of the bottom 10%. Now take account of taxes and benefits. Then add in the effects of the NHS, free education for all children and so on. Government services. We end up with a ratio of 4 to 1. Life as it’s actually lived gives the top 10% four times the final income – income being defined by consumption of course – of the bottom 10%.

That’s not a high level of inequality.

January 28, 2019

On modern notions of privacy

Terry Teachout does a daily “Almanac” post of a short quotation he’s collected along the way — generally much shorter snippets than my sometimes epic-length QotD postings. A few weeks ago, he posted a short quotation from Charles Stross on the impending loss of privacy, from his SF novel Rule 34:

“Privacy is a peculiarly twentieth-century concept, an artifact of the Western urban middle classes: Before then, only the super rich could afford it, and since the invention of e-mail and the mobile phone, it has largely slipped away.”

Far be it from me to disagree with Charles, but privacy even for the wealthy in the past was an unusual thing: unless you’re of such a refined and haughty sensibility that you literally don’t notice all the servants in your house. Being wealthy meant not having to do a lot of things for yourself, from getting washed and dressed to opening doors and windows to preparing and serving food. Servants were cheap and plentiful, and were everywhere in the worlds of the wealthy and powerful.

Poor people generally had no privacy because the vast majority of them lived in single-room dwellings with their extended families — and outside the towns, even including some of their livestock. All of your activity was in the close company of your family at pretty much all times.

Middle-class people would have at least a servant or two in residence — that was one of the differentiators that helped indicate their social and economic status. Someone would need to do all the necessary work around the house that we no longer need to do thanks to electricity, plumbing, central heating, and all our modern conveniences. At the very least you’d have a cook, a maid, and a footman. If you had a horse-drawn vehicle (much more of a luxury), you’d need staff for the stable and to operate the vehicle (you wouldn’t drive your own carriage most of the time).

Lower middle-class families would also rarely have anything that a modern person would understand as privacy. Aside from a few servants, most tradesmen would have apprentices living in the house, and the house would generally also be the seat of business. Not anywhere near as crowded as houses of the poor, but not particularly conducive to privacy.

I suspect that our modern notion of privacy would have been so rare in historical terms that only certain monastic orders would even come close to it, in the same way that a relatively brief historical period (the 1940s-1960s) defined what “childhood” was supposed to be for most westerners.

November 22, 2018

This is why tax cuts are always criticized for benefitting the rich

Rebecca Zeines and Jon Miltimore explain why newspaper headlines and TV anchors always seem to decry any tax cut as being disproportionally beneficial to the wealthy:

But crucial facts are often missing in these articles. As a recent Bloomberg piece explained, two key points tend to be overlooked in articles written by media outlets and progressive tax proponents:

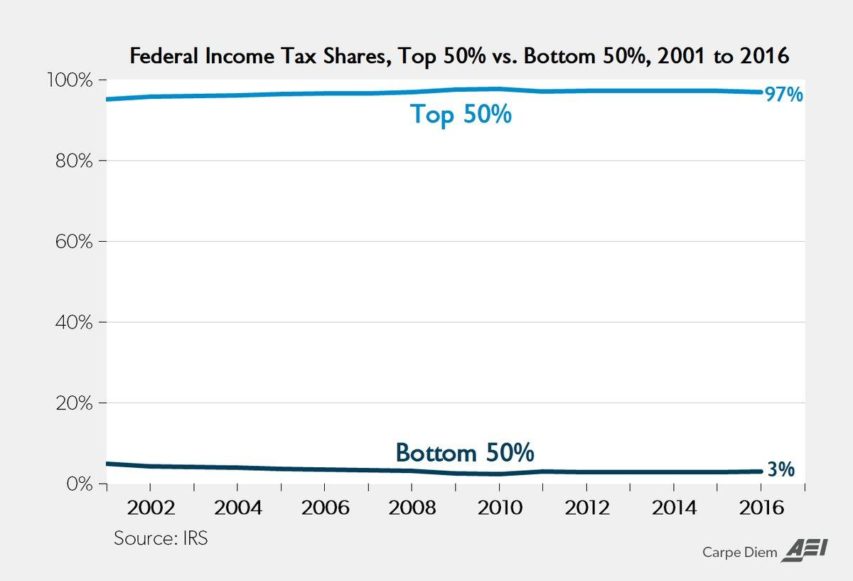

- The top 1 percent paid a greater share of individual income taxes (37.3 percent) than the bottom 90 percent combined (30.5 percent).

- The top 50 percent of all taxpayers paid 97 percent of total individual income taxes.

These numbers date back to 2016 but remain applicable in 2018.

These data show that the bottom 50 percent of US taxpayers paid just 3 percent of total income taxes in 2016, while the top 50 percent accounted for 97 percent.

Here is a wonderful visual representation of this dynamic, courtesy of Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute:

There is a clear correlation between economic freedom and prosperity, and tax climate is a key component of economic freedom.

Economist Dan Mitchell explains it best: Heavy taxation destroys entrepreneurship. The more money is taxed out of the private sector, the less is available for investment, development, and worker compensation (recall that after Trump’s tax bill was enacted, many businesses raised workers’ wages and offered bonuses).

Efforts to improve America’s tax climate are consistently and predictably derided as tax cuts for “the rich.” But, as the above diagram shows, it’s quite impossible to offer people a comparatively huge tax cut when they’re paying a comparatively tiny percentage of income taxes.

September 15, 2018

NDP leader Jagmeet Singh hits a rough patch

Colby Cosh on the federal NDP leader’s travails:

The thing about being a New Democratic Party leader is that there’s an oh-so-fine class line to walk, a line that is easier for the leaders of less socially concerned parties. No one really expects that the leader of the NDP will actually be a working-class person, and since Ed Broadbent’s time, even the expectation that the leader will have been raised working-class has diminished. Jack Layton and Thomas Mulcair have so many politicians brachiating in their family trees that if they lived in the U.K. they would probably have had peerages to renounce.

But until Jagmeet Singh came along, there was a still norm of personal austerity to be observed — a natural limit to how expensively one could dress, and how much conspicuous consumption one could indulge, while still serving up an NDP leader’s generous portion of lectures against selfishness and greed. Singh is the son of a psychiatrist: the tuition for the private American high school from which he graduated is, for the 2018-19 school year, US$31,260. He has been in GQ for his bespoke suits, and owns (according to Toronto Life) two Rolexes.

(I confess that the watches set me off. Rolexes aren’t arty like a Patek Philippe; they don’t do anything cool. They’re mostly kind of ugly. They are a pure, cold signifier of brute pride in wealth.)

Making Singh leader of the federal NDP was audacious. If ordinary New Democrats had a problem with his image and tastes, they probably felt that, with Justin Trudeau leading the Liberals, they had plenty of wiggle room on the left for a handsome leader with some celebrity dazzle. Trudeau had appetizing potential to make ghastly errors of Richie Rich cluelessness, and has delivered.

But it seems Singh will not entirely be able to avoid the day of reckoning, the day of exposure to a stricter New Democratic standard. The leader, as you probably know, has a problem in Saskatchewan, the party’s traditional heart. In May he threw MP Erin Weir out of the national NDP caucus after an independent investigation “upheld” complaints of harassment, sexual and otherwise, against Weir. Weir’s many friends in Saskatchewan are unhappy with how the case was handled.

August 5, 2018

QotD: Risk aversion

… let’s step back and ask ourselves what insurance is for. Classical economics has an answer: people are risk-averse, which means that they will pay good money to reduce the variability of outcomes they face. If home insurance guards against the loss of a million pounds when my house burns down, I’m happy to buy the insurance even though the insurance company expects to make a profit from it.

But this risk aversion emerges from the fact that money is worth more to poor people than to rich people. Gaining a million pounds would make me rich but losing a million pounds would make me poor. I should not gamble a million pounds on the toss of a coin, because the million pounds I might lose is more precious to me than the million pounds I might gain.

As so often with classical economics, this is an excellent description of how we should behave. It is not such an excellent description of how we actually do behave. Risk aversion can only explain why we insure large risks. It cannot explain why we insure small ones. This is because risk aversion turns on the idea that an extra pound is worth more if you are poor than if you are rich. But having to replace a phone is not going to make the difference between poverty and wealth.

In one of my favourite economics articles, written in 2001, the behavioural economists Richard Thaler and Matthew Rabin point out that anyone who rejects a 50/50 gamble to win £10.10 or lose £10 — apparently a reasonable enough taste for caution — cannot possibly be doing so because of risk aversion. (The degree of risk aversion necessary would mean that the same individual wouldn’t risk £1,000 on the toss of a coin for all the money in the world.) Risk aversion simply cannot explain why anyone would turn down that fractionally favourable gamble. And it cannot explain why anyone would insure a mobile phone.

A better explanation is that we tend to view risks in isolation. Rather than telling ourselves “a lost mobile phone would lower my lifetime wealth by 0.005 per cent”, we tell ourselves “it would be so annoying to have to pay for a new mobile phone”. Isolating and obsessing about risks in this way is arbitrary and illogical. But that does not mean we don’t do it.

Tim Harford, “How insurers keep the money-pump flowing”, TimHarford.com, 2016-09-21.

July 16, 2018

QotD: The Great Enrichment

Look at the astonishing improvements in China since 1978 and in India since 1991. Between them, the countries are home to about four out of every 10 humans. Even in the United States, real wages have continued to grow — if slowly — in recent decades, contrary to what you might have heard. Donald Boudreaux, an economist at George Mason University, and others who have looked beyond the superficial have shown that real wages are continuing to rise, thanks largely to major improvements in the quality of goods and services, and to nonwage benefits. Real purchasing power is double what it was in the fondly remembered 1950s — when many American children went to bed hungry.

What, then, caused this Great Enrichment?

Not exploitation of the poor, not investment, not existing institutions, but a mere idea, which the philosopher and economist Adam Smith called “the liberal plan of equality, liberty and justice.” In a word, it was liberalism, in the free-market European sense. Give masses of ordinary people equality before the law and equality of social dignity, and leave them alone, and it turns out that they become extraordinarily creative and energetic.

The liberal idea was spawned by some happy accidents in northwestern Europe from 1517 to 1789 — namely, the four R’s: the Reformation, the Dutch Revolt, the revolutions of England and France, and the proliferation of reading. The four R’s liberated ordinary people, among them the venturing bourgeoisie. The Bourgeois Deal is, briefly, this: In the first act, let me try this or that improvement. I’ll keep the profit, thank you very much, though in the second act those pesky competitors will erode it by entering and disrupting (as Uber has done to the taxi industry). By the third act, after my betterments have spread, they will make you rich.

And they did.

Dierdre N. McCloskey, “The Formula for a Richer World? Equality, Liberty, Justice”, New York Times, 2016-09-02.

July 4, 2018

QotD: “The world is rich and will become still richer. Quit worrying”

Not all of us are rich yet, of course. A billion or so people on the planet drag along on the equivalent of $3 a day or less. But as recently as 1800, almost everybody did.

The Great Enrichment began in 17th-century Holland. By the 18th century, it had moved to England, Scotland and the American colonies, and now it has spread to much of the rest of the world.

Economists and historians agree on its startling magnitude: By 2010, the average daily income in a wide range of countries, including Japan, the United States, Botswana and Brazil, had soared 1,000 to 3,000 percent over the levels of 1800. People moved from tents and mud huts to split-levels and city condominiums, from waterborne diseases to 80-year life spans, from ignorance to literacy.

You might think the rich have become richer and the poor even poorer. But by the standard of basic comfort in essentials, the poorest people on the planet have gained the most. In places like Ireland, Singapore, Finland and Italy, even people who are relatively poor have adequate food, education, lodging and medical care — none of which their ancestors had. Not remotely.

Inequality of financial wealth goes up and down, but over the long term it has been reduced. Financial inequality was greater in 1800 and 1900 than it is now, as even the French economist Thomas Piketty has acknowledged. By the more important standard of basic comfort in consumption, inequality within and between countries has fallen nearly continuously.

Dierdre N. McCloskey, “The Formula for a Richer World? Equality, Liberty, Justice”, New York Times, 2016-09-02.

June 30, 2018

Wealthy virtue-signalling hurts the poor

At Catellaxy Files, Rafe Champion discusses some of the points raised by Matt Ridley in his recent book:

Essentially, the poor pay for the virtue-signalling of the rich. Dr Matt Ridley opens chapter 14 of Climate Science: The Facts with some blunt claims.

Here is a simple fact about the world today. Climate change is doing more good than harm. Here is another fact. Climate change policy is doing more harm than good.

On top of that he points out that the poor are carrying the cost of today’s climate policy. That is something for the ALP [Australian Labour Party] and the social justice warriors to think about.

This should remind people of another great postwar example of destructive virtue-signalling – massive foreign aid to the developing nations aka the Third World. That did more harm than good for the people of the Third World, apart from the crony criminals in power. The great Lord Peter Bauer was onto that very smartly, starting in the 1940s and his findings have been consolidated lately, notably by William Easterly [in] The White Man’s Burden: Why the west’s efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. There are exceptions to the rule such as hands-on medical care and private education.

Ridley mentions in passing some of the cases where apparently smart people have made very bad calls, starting with a prominent and wealthy leftwinger who he debated on TV. Faced with the charge that climate policy was hurting the poor he replied “But what about my grandchildren?”. As though the future wellbeing of the presumably affluent and privileged grandchildren of the talking head might be threatened by policies that help the poor who are with us at present. Ridley also cited a son of Charles Darwin who thought that eugenic breeding programs were essential to save civilization and Paul Ehrlich who in 1972 predicted that millions would die due to over-population (prompting the one-child policy in China).

June 11, 2018

L. Neil Smith on the Koch brothers and the libertarian movement

In the latest issue of the Libertarian Enterprise, L. Neil Smith discusses his experiences working with the Koch brothers:

It says here that David Koch is retiring. In case you don’t know, he is the younger of two oil billionaire brothers associated with the libertarian movement who bankrolled the Cato Institute, and whom “progressives” love to hate, automatically blaming them for what little they don’t blame Donald Trump for.

Genuine libertarians and conservatives don’t like them much, either, for a variety of reasons. My own first is that I served on the 1977 Libertarian Party National Platform Committee with Charlie, David’s older brother and found him to be a timid, unimaginative soul, more concerned with credibility and respectability than with truth or principle. At the time, the think-tank he and his brother created was attempting to turn the LP into a wholly-owned subsidiary (David ran in 1980 for Vice President with Ed Clark), and I didn’t like that, either.

The Koch brothers are also open-borderists, siding with establishment Republicans like that smirk-weasel Paul Ryan who want an imported servant-class they can abuse. I’ve changed my mind on that issue for good and sufficient reasons, and they ought to be good and sufficient for the Koch Brothers, too, if they were really libertarians. American culture is unique and wonderful; I do not want to see it changed or destroyed as the cultures of Sweden and England are being, by uncontrolled mass immigration. Letting a lot of Third Worlders into the United States of America is like letting a lot of Californians into Colorado. Pretty soon it’ll be just like the mess they made and left behind.

We have a saying here: “Don’t Californicate Colorado”.

David is retiring, it says here, due to an extremely long bout with prostate cancer. It does not say what his prognosis is. My own father, whom I miss every day, fought prostate cancer for six ghastly years and died. I’m sorry David has it now; I would not wish that fate on anybody.

But the reason I’m writing this is to speak the truth, to a great big pile of money, if not to power. The Kochs don’t have power because they don’t have a clue how to spend money politically, and, among other counter-productive follies, they threw their dough away with all four hands, supporting a think-tank incapable of reaching the people by the millions the way Donald Trump has. I have never known anyone who read a paper produced by the Cato Institute or listened to a lecture given by one of their wonks — except other wonks.

May 22, 2018

QotD: Capitalism is the most feminist economic system ever

We really do need to be pointing out that the Good Old Days are now. Both technological advance and productivity growth have been driven by that combination of capitalism and markets. Capitalism, in its lust for profits, leading to the invention. Markets and the ability to copy what works being what creates the general uplift in standards by the spreading and wide use of those inventions.

The net effect of this has been, well, it’s been to make women’s lives vastly better. Starting with the point that many women actually have lives as a result. Childbirth has moved from being the leading cause of female death* to a mild risk which kills very few – each one a tragedy which is why we’re so happy that we have reduced that risk. We’ve automated all the heavy lifting in society meaning that women can indeed, with their generally lighter musculature, compete in near all areas of work. We’ve done more automation of household drudgery than we have of anything else too, freeing the distaff side from that chain upon their ambitions.

We’ve even freed all from the child bearing consequences of bonking – much to the great pleasure of man and woman alike.

Women today are the most privileged, richest, group of women who have ever stumbled across the surface of this planet. And in comparison to the men in their society they’re the most equal too. All of which leads to an interesting question. Just why are they whining so much?

*Possibly an exaggeration but not much of one. Certainly not about the mid 19th century before Semmelweiss.

Tim Worstall, “Capitalism Is The Most Feminist Economic System Ever”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-04-30.

April 30, 2018

The Empire of Mali – Mansa Musa – Extra History – #3

Extra Credits

Published on 28 Apr 2018Mansa Musa is remembered as the richest person in the entire history of the world, but he also worked hard to establish the empire of Mali as a political and even religious superpower. However, his excessive wealth started creating bigger problems…

April 11, 2018

Penn & Teller: Dalai Lama and Tibet

infinit888

Published on 13 May 2008Mainstream media seems to be only pushing the story about an oppressed Tibet and referring to the Dalai Lama as a saint.

This is a compilation of clips from Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! “Holier Than Thou” speaking about Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

QotD: Wealth hath its (social) privileges

Rich people — left, right, center — think what they have to say is interesting because they get used to people treating them that way.

Ramesh Ponnuru, Twitter, 2016-07-21.