This is why planning an economy simply doesn’t work. Issue targets that must be hit and people game the system to hit the targets without actually doing the desired underlying thing. Or, as it is formally constituted:

Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.

Or as it has been reformulated:

Goodhart’s law is an adage named after economist Charles Goodhart, which has been phrased by Marilyn Strathern as: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” One way in which this can occur is individuals trying to anticipate the effect of a policy and then taking actions which alter its outcome.

Set a target for tonnes of shoes and you get one tonne shoes. Set a target for 100 shoes and you get 100 left feet. Set a target for being on time and people fiddle their definition of time.

It is, by the way, entirely fine to insist that airlines play fair with telling us how long a flight will take. You said it will take 4 hours, then 4 hours should be about the time it takes. Yes, sure, we understand, airports, crowded places. Idiot passengers forget to board, luggage must be taken off. Winds vary, thunderstorms happen, French air traffic controllers actually turn up to work today, their one day in seven. Sure, there’re lots of variables. But if you say it’s about four hours then it should be about four hours. Great.

But to complain that they pad their number a bit is ludicrous. We’re holding their feet to the fire, insisting that an underestimate will lead to financial costs. Thus, obviously, they will overestimate. That’s not really even Goodhart’s Law, that’s just human beings. But then, as we know, those who would plan everything don’t deal well with the existence of people, do they?

Tim Worstall, “Goodhart’s Law Applies To Economies, To Everything – Why Not Scheduled Airline Flight Times?”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-08-27.

December 14, 2020

QotD: Goodhart’s law

December 13, 2020

QotD: The statistical “Rule of Silicone Boobs”

If it’s sexy, it’s probably fake.

“Sexy” means “likely to get published in the New York Times and/or get the researcher on a TEDx stage”. Actual sexiness research is not “sexy” because it keeps running into inconvenient results like that rich and high-status men in their forties and skinny women in their early twenties tend to find each other very sexy. The only way to make a result like that “sexy” is to blame it on the patriarchy, and most psychologist aren’t that far gone (yet).

[…]

Anything counterintuitive is also sexy, and (according to Rule 2) less likely to be true. So is anything novel that isn’t based on solid existing research. After all, the Times is the newspaper business, not in the truthspaper one.

Finding robust results is very hard, but getting sexy results published is very easy. Thus, sexy results generally lack robustness. I personally find a certain robustness quite sexy, but that attitude seems to have gone out of fashion since the Renaissance.

Jacob Falkovich, “The Scent of Bad Psychology”, Put a Number On It!, 2018-09-07.

November 7, 2020

Misunderstanding what is meant by “mineral reserves”

It seems to happen almost as regularly as Old Faithful, as someone blows a virtual gasket over the reserves of this or that mineral “running out” in x number of years. Tim Worstall explains why this is a silly misunderstanding of what the term “mineral reserves” actually means:

“Aerial view of a small mine near Mt Isa Queensland.” by denisbin is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

It’s not exactly unusual to see some environmental type running around screaming because mineral reserves are about to run out. The Club of Rome report, the EU’s “circular economy” ideas, Blueprint for Survival, they’re all based upon the idea that said reserves are going to run out.

They look at the usual listing (USGS, here) and note that at the current rate of usage reserves will run out in 30 to 50 years. Entirely correct they are too. It’s the next step which is such drivelling idiocy. For the claim then becomes that we will run out of those metals, those minerals, when the reserves do. This being idiot bollocks.

For a mineral reserve is, as best colloquial language can put it, the stuff we’ve prepared for use in the next few decades. Like, say, 30 to 50 years. That we’re going to run out of what we’ve got prepared isn’t a problem. For we’ve an entire industry, mining, whose job to to go prepare some more for us to use.

[…] A mineral reserve is something created by the mining company. Created by measuring, testing, test extracting and proving that the mineral can be processed, using current technology, at current prices, and produce a profit. Proving that this is not just dirt but is in fact ore.

Mineral reserves are things we humans make, not things that exist.

October 15, 2020

QotD: What the GDP is failing to show (even though it’s there)

There simply isn’t a technology that has come anywhere close to arriving in the hands of actual users as fast as the smartphone and mobile internet. The next closest competitor is the mobile phone itself. All others running distant third and behind.

Our problem is that we know technological revolutions produce growth. Yet economic growth is limp at best, meagre perhaps a better description. So, there’s something wrong here. Either our basic understandings about how growth occurs are wrong and we [are] loathe to agree to that. Not because too much is bound up in that understanding but because too much of it makes sense. The other explanation is that we’re counting wrong.

[…]

We know that we’ve not quite got new products and their falling prices in our estimates of inflation quite correctly. They tend to enter the inflation indices after their first major price falls, meaning that inflation is always overstated. Given that the number we really look at is real growth – nominal growth minus inflation – this means we are consistently underestimating real growth.

[…]

The more we dig into this the more convinced I am that our only real economic problem at present is counting. Everything makes sense if we are counting output and inflation incorrectly, under-estimating the first, over- the second. If we are doing that – and we know that we are, only not quite to what extent – then all other economic numbers make sense. We’re in the midst of a large technological change, we’ve full employment by any reasonable measure, wages and productivity should be rising strongly. If we’re mismeasuring as above then those two are rising strongly, we’re just not capturing it. Oh, and if that’s also true then inequality is lower than currently estimated too.

The thing is, the more we study the details of these questions the more it becomes clear that we are mismeasuring, and mismeasuring enough that all of the claimed problems, the low growth, low productivity rises, low wage growth, simply aren’t there in the first place. And if they ain’t then nothing needs to be done about them, does it? Except, perhaps, count properly.

Tim Worstall, “Where’s All The Economic Growth? Goldman Sachs Blames Apple’s iPhone”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-07-03.

October 9, 2020

QotD: How to analyze complex multivariate systems for the popular press

- Choose a complex and chaotic system that is characterized by thousands or millions of variables changing simultaneously (e.g. climate, the US economy)

- Pick one single output variable to summarize the workings of that system (e.g. temperature, GDP)

- Blame (or credit) any changes to your selected output variable on one single pet variable (e.g. capitalism, a President from the other party)

- Pick a news outlet aligned with your political tribe and send them a press release

- Done! You are now a famous scientist. Congratulations.

Warren Meyer, “Modern Guide to Analyzing Complex Multivariate Systems”, Coyote Blog, 2018-06-25.

August 28, 2020

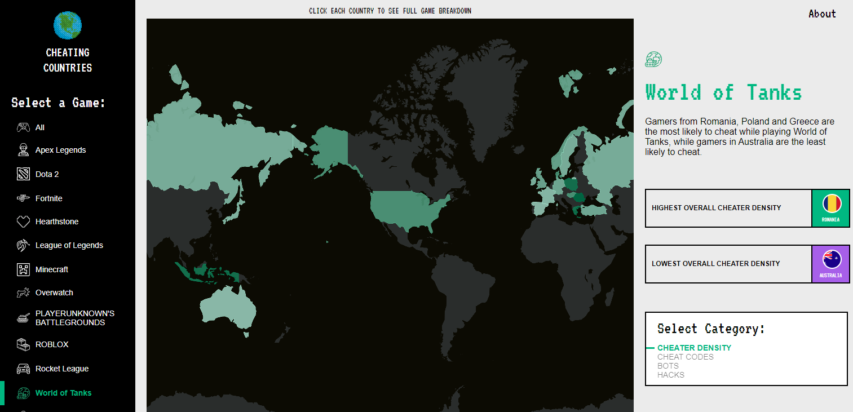

National “cheater density” for popular online games

Richard Currie summarizes the findings of Ruby Fortune’s cheater research (note that there’s no data on China because reasons):

Ever torn your keyboard from the desk and flung it across the room, vowing to find the “scrub cheater” who ended your run of video-gaming success? Uh, yeah, us neither, but a study into the crooked practice might help narrow down the hypothetical search.

The research, carried out by casino games outfit Ruby Fortune, has produced a global heatmap of supposed cheater density.

According to the website, this was done by analysing “search trend and search volume data to reveal where in the world is most likely to cheat while playing online multiplayer video games”. The report looks at the frequency of search engine queries for the most-played video games and measures them against searches for related cheat codes, hacks and bots, to show which country has the highest density of cheaters, and which cheat categories are the most popular in each location.

[…]

There is a massive hole in the data, however, thanks to the Great Firewall of China, which has a terrible reputation for ruining the experience of online games.

If there was any doubt that the Middle Kingdom would otherwise take Brazil’s crown, consider that Dell once advertised a laptop for the market by saying it was especially good for running PUBG plugins to “win more at Chicken Dinner”, a reference to the “Winner winner chicken dinner” message that comes up on a victory screen.

Data from the Battle Royale granddad’s anti-cheat tech provider, BattlEye, has also suggested that at one point 99 per cent of banned cheaters were from China.

August 16, 2020

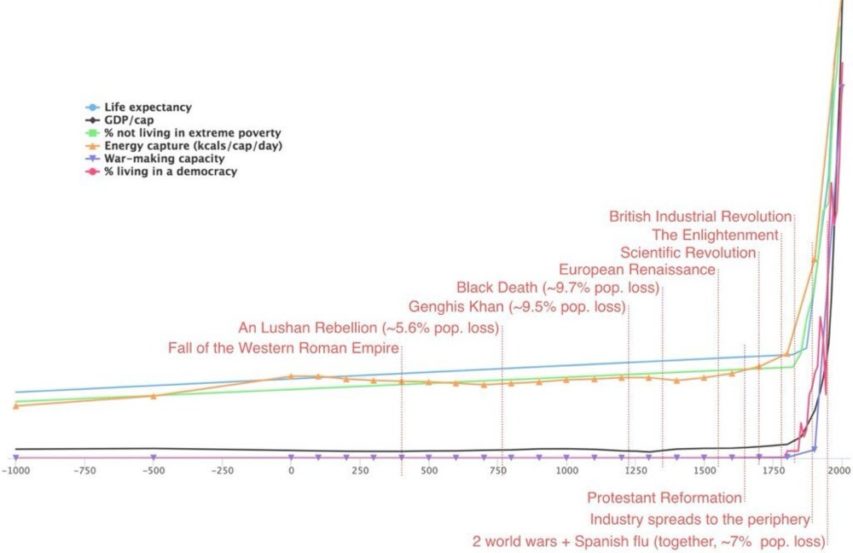

This is a “hockey stick” graph you can believe

Brian Micklethwait says this graph, unlike the more famous (debunked) “hockey stick”, shows one of the most important moments in human history:

If that graph, or another like it, is not entirely familiar to you, then it damn well should be. It pinpoints the moment when our own species started seriously looking after its own creature comforts. This was, you might say, the moment when most of us stopped being treated no better than farm animals, and we began turning ourselves into each others’ pets.

Patrick Crozier and I will be speaking about this amazing moment in the history of the human animal in our next recorded conversation. That will, if the conversation happens as we hope and the recording works as we hope, find its way to here.

I’m not usually one for podcasts, in the same way that I’m not an audiobook user: I find I’m unable to do other things while listening to the spoken word, and it’s always far faster to read a text than to have it read to you. In this particular case, I might try to make an exception, and give up hope of doing anything else productive while I listen.

August 8, 2020

Andrew Sullivan – “[T]he Kendi test: does the staff reflect the demographics of New York City as a whole?”

In his latest Weekly Dish, Andrew Sullivan looks at an earnest diversity initiative of The Newspaper Guild of New York:

I’m naming this after Ibram X. Kendi because his core contribution to the current debate on race is the notion that “any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups” is racist. Intent is irrelevant. I don’t think many sane people believe A.G. Sulzberger or Dean Baquet are closet bigots. But systemic racism, according to Kendi, exists in any institution if there is simply any outcome that isn’t directly reflective of the relevant racial demographics of the surrounding area.

The appeal of this argument is its simplicity. You can tell if a place is enabling systemic racism merely by counting the people of color in it; and you can tell if a place isn’t by the same rubric. The drawback, of course, is that the world isn’t nearly as simple. Take the actual demographics of New York City. On some measures, the NYT is already a mirror of NYC. Its staff is basically 50 – 50 on sex (with women a slight majority of all staff on the business side, and slight minority in editorial). And it’s 15 percent Asian on the business side, 10 percent in editorial, compared with 13.9 percent of NYC’s population.

But its black percentage of staff — 10 percent in business, 9 percent in editorial — needs more than doubling to reflect demographics. Its Hispanic/Latino staff amount to only 8 percent in business and 5 percent in editorial, compared with 29 percent of New York City’s demographics, the worst discrepancy for any group. NYT’s Newsroom Fellowship, bringing in the very next generation, is 80 percent female, 60 percent people of color (including Asians), and, so far as I can tell, one lone white man. And it’s why NYT‘s new hires are 43 percent people of color, a definition that includes Asian-Americans.

But notice how this new goal obviously doesn’t reflect New York City’s demographics in many other ways. It draws overwhelmingly from the college educated, who account for only 37 percent of New Yorkers, leaving more than 60 percent of the city completed unreflected in the staffing. It cannot include the nearly 19 percent of New Yorkers in poverty, because a NYT salary would end that. It would also have to restrict itself to the literate, and, according to Literacy New York, 25 percent of people in Manhattan “lack basic prose literary skills” along with 37 percent in Brooklyn and 41 percent in the Bronx. And obviously, it cannot reflect the 14 percent of New Yorkers who are of retirement age, or the 21 percent who have yet to reach 18. For that matter, I have no idea what the median age of a NYT employee is — but I bet it isn’t the same as all of New York City.

Around 10 percent of staffers would have to be Republicans (and if the paper of record nationally were to reflect the country as a whole, and not just NYC, around 40 percent would have to be). Some 6 percent of the newsroom would also have to be Haredi or Orthodox Jews — a community you rarely hear about in diversity debates, but one horribly hit by a hate crime surge. 48 percent of NYT employees would have to agree that religion is “very important” in their lives; and 33 percent would be Catholic. And the logic of these demographic quotas is that if a group begins to exceed its quota — say Jews, 13 percent — a Jewish journalist would have to retire for any new one to be hired. Taking this proposal seriously, then, really does require explicit use of race in hiring, which is illegal, which is why the News Guild tweet and memo might end up causing some trouble if the policy is enforced.

And all this leaves the category of “white” completely without nuance. We have no idea whether “white” people are Irish or Italian or Russian or Polish or Canadians in origin. Similarly, we do not know if “black” means African immigrants, or native black New Yorkers, or people from the Caribbean. 37 percent of New Yorkers are foreign-born. How does the Guild propose to mirror that? Ditto where staffers live in NYC. How many are from Staten Island, for example, or the Bronx, two places of extremely different ethnic populations? These categories, in other words, are incredibly crude if the goal really is to reflect the actual demographics of New York City. But it isn’t, of course.

My point is that any attempt to make a specific institution entirely representative of the demographics of its location will founder on the sheer complexity of America’s demographic story and the nature of the institution itself. Journalism, for example, is not a profession sought by most people; it’s self-selecting for curious, trouble-making, querulous assholes who enjoy engaging with others and tracking down the truth (at least it used to be). There’s no reason this skillset or attitude will be spread evenly across populations. It seems, for example, that disproportionate numbers of Jews are drawn to it, from a culture of high literacy, intellectualism, and social activism. So why on earth shouldn’t they be over-represented?

And that’s true of other institutions too: are we to police Broadway to make sure that gays constitute only 4 percent of the employees? Or, say, nursing, to ensure that the sex balance is 50-50? Or a construction company for gender parity? Or a bike messenger company’s staff to be reflective of the age demographics of the city? Just take publishing — an industry not far off what the New York Times does. 74 percent of its employees are women. Should there be a hiring freeze until the men catch up?

July 15, 2020

QotD: State and private charity

Some social and political analysts regard private help as a bad thing. They speak of the “problem” of food banks, and of America’s “miserly” support for poorer countries. In fact food banks are a solution, not a problem. Private generosity has leapt into the breach to help tide people over temporary problems. The great majority of food bank users do so only once.

Similarly with US aid to poorer countries. The United States is regularly berated for being very low on the list of aid givers, but this only applies to government-to-government aid. Once the private contributions made by Americans to people in poorer countries are counted in, the US rises to the top. In fact US private help is better spent, usually going to people to spend in towns and villages in the local economy, rather than on gold palaces and white elephant steel mills in the desert.

Part of this mismatch arises from the fact that these analysts seem to wear spectacles that admit only light of a political wavelength and ignore private generosity. The latest victim of this myopia is the “bank of mom and dad.” It is assumed to be a bad thing that young people should turn to mom and dad to help out with deposits and mortgages.

“Richard”, “Is Private Help a Bad Thing? – Political Spectacles of the Left”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-04-02.

June 19, 2020

The economy isn’t all huge corporations and government

Paul Sellers reminds us that the economy is far more than just the big names that get mentioned in the financial pages:

Independents in micro-businesses are few and far between and often hard to discover, despite the internet’s ever-increasing web of enterprises. The backbone of British industry is made up of small, independent people striving to retain a measure of individualism, independence and entrepreneurialism in their lives. Statistics from 2019 show that in Britain there were 5.82 million small businesses responsible for 99.3% of the total business output in the UK.

Small businesses here comprise those with 0-49 employees and digging deeper still into what might at first seem more irrelevant than relevant is that the niche that small businesses fill in the real world of enterprise. Over 76% of businesses are operated by one-man bands; single-person enterprises who operate alone comprise almost 4.5 million men and women. With an additional 1.15 million micro-business (1-9 employees) around 95% of businesses here operate on a strength of under just 10 people. So over 99% of small to medium business enterprises, that’s zero to 249 employees, but only 0.6% have a workforce of 50-249 employees. Less than 4% are small businesses with 10-49 staff members and get this, over 95% operate as micro-businesses with 0-9 employees. What does this tell you about businesses output? What it tells me is how little of this is newsworthy by the mass media manufacturing companies (Like BBC News and ITV, Sky and so on) who constantly tell us about how many this massive company or that massive company is laying off and how little this really affects our economy because the little guys still get out into their little micro-shops and make what cannot work work.

June 2, 2020

QotD: Economic inequality

Economic inequality […] is both highly moralized (right-thinking people agree it’s the root of all evil) and intellectually devilishly complex, far more than people acknowledge. For example, if “the bottom fifth” earns the same proportion of income in 1980 and 2010, it doesn’t mean anyone’s income stagnated: these “fifths” are different people, and they earn a fifth of different totals. Also, it’s not clear that inequality (as opposed to poverty) is a moral abomination, or that reducing it is progress. As Walter Scheidel argues in The Great Leveler (another superb book of 2017), the most effective ways of reducing inequality are epidemics, massive wars, violent revolutions and state collapse.

Steven Pinker, “Twenty Questions with Steven Pinker”, Times Literary Supplement, 2018-02-18.

May 31, 2020

QotD: Measuring what can be measured

There are things that can be measured. There are things that are worth measuring. But what can be measured is not always what is worth measuring; what gets measured may have no relationship to what we really want to know. The costs of measuring may be greater than the benefits. The things that get measured may draw effort away from the things we really care about. And measurement may provide us with distorted knowledge – knowledge that seems solid but is actually deceptive.

Jerry Z. Muller, The Tyranny of Metrics, 2018.

May 24, 2020

QotD: The “balance of trade”

Joseph Schumpeter [wrote in] History of Economic Analysis (1954):

The first thing to observe about this concept [of the balance of trade] is that it is in fact an analytic tool. The balance of trade is not a concrete thing like a price or a load of merchandise.

Yes (although it is even more accurate to describe the balance of trade as an accounting convention). If, for example, it had been decided to record purchases and sales of real estate on the current account rather than on the capital account, the size of each country’s current-account deficit or surplus would be different even though absolutely nothing real in the national or global economy would be changed. And yet to hear any of the many protectionists bemoan their country’s trade- or current-account deficit is to hear people who typically mistake this accounting convention for a concrete thing. Such complaints almost always reflect utter misunderstanding of so-called “trade balances.”

Don Boudreaux, “Bonus Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2018-01-21.

May 9, 2020

Lies, damned lies, and even-more-damned statistics

David Warren does not trust “the numbers” (and I think he’s quite right to doubt):

At some point — but it is seldom a discrete moment in space or time — the weight of the anecdotal in science, or that of the circumstantial in law, becomes overwhelming. This is the opposite of a statistical fact, in part because there are no statistical facts. I am reminded of this whenever the “scientific” control freaks of statistics lay down some law, indifferent to the Law in nature. The difference between 999,999 and one million is, in any imaginable situation, not a difference at all. Where it is made the basis for a decision, that decision is arbitrary, and not infrequently, cruel. By contrast, such differences as those between pregnant and not pregnant, dead and not dead, are unchallengeably significant. They are in the realm of meaning.

I am reminded of this hourly or better, these days, when consulting the news. All readers of the mass media (accurately described by Trump as “fake news”) are being covered, constantly, by the vomit of statistics — few with any context, and many knowingly false. They “look scientific,” which is to say, they answer to the moron’s conception of science. In “disciplines” like economics, today, and throughout the other social sciences, the participants sleepwalk. Nobel prizes are given out for numerical sludge, presented to the purpose of selling one destructive “policy” or another, that will be imposed on real, live, particular human beings. The same is true of the “mathematical biology” that has disinformed all our public health “professionals.”

The Red Chinese Batflu, now transforming our world, is a spectacular case in point. Not only the epidemiological projections, but even the counts of dead and wounded, are taken on faith — from people who are characteristically faithless. Information on prevention and cures is hostage to the work of statisticians. “Double blind tests,” which would be absolutely immoral — wicked — on human subjects facing life or death — are demanded by our medical apes.

May 5, 2020

The perverse incentives of the Wuhan Coronavirus outbreak

David Warren has clearly taken his cynical pills today:

The daily count of deaths from the Red Chinese Batflu is among the prized, scare-mongering features of our mass media. I am among those who consider these numbers to be significantly overstated, for a reason that Nikolai Gogol would understand. Each corpse is worth cash to some public authority, usually from a higher authority; and as always, finally from the taxpayers. Each also saves money for government programmes, that can be reallocated to the purchase of new votes. As the corpse providers from this virus are very old, and suffering from other life-threatening conditions, in almost every case, this statistical inflation is easy to perform. Death certificates are issued for any who died with “Covid-19,” whether or not they died from it, and more are then added of those who were never tested. Anything respiratory will do. It’s all judgement calls — on which side of the bread is buttered.

Compare if you will the Hong Kong Flu of 1968 and 1969. I was just reading a memoir, from down that memory hole. The death toll was actually higher then, than ours is now, and from within a smaller population; the victims included children and the young. Yet there were no interruptions in economic life; no public emergency theatricals; and at the height of the second wave of that scourge, we had events like Woodstock. (Those were the days, my friend.)

A neat way to correct for all our “judgement calls” might be to look at overall death rates, and see if they have risen or fallen. It is too early to get a clear view, but soon it may be too late, for vested interests will have tampered with them. All my life I have been learning to trust statistics, less — especially from those who dress in labcoats and affect that earnest look. Sometimes an exception must be considered, however. An unpredictable minority may be honest; some others might get numbers right by mistake.